A Visitor's Guide to the Jebel Barkal Temples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators this is max size of image at 200 dpi; the sil is low res and for the comp only. if approved, needs to be redone carefully American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators American Federation of Arts © 2006 American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs: Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum is organized by the American Federation of Arts and The British Museum. All materials included in this resource may be reproduced for educational American Federation of Arts purposes. 212.988.7700 800.232.0270 The AFA is a nonprofit institution that organizes art exhibitions for presen- www.afaweb.org tation in museums around the world, publishes exhibition catalogues, and interim address: develops education programs. 122 East 42nd Street, Suite 1514 New York, NY 10168 after April 1, 2007: 305 East 47th Street New York, NY 10017 Please direct questions about this resource to: Suzanne Elder Burke Director of Education American Federation of Arts 212.988.7700 x26 [email protected] Exhibition Itinerary to Date Oklahoma City Museum of Art Oklahoma City, Oklahoma September 7–November 26, 2006 The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens Jacksonville, Florida December 22, 2006–March 18, 2007 North Carolina Museum of Art Raleigh, North Carolina April 15–July 8, 2007 Albuquerque Museum of Art and History Albuquerque, New Mexico November 16, 2007–February 10, 2008 Fresno Metropolitan Museum of Art, History and Science Fresno, California March 7–June 1, 2008 Design/Production: Susan E. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

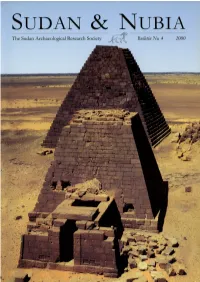

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Preliminary Report on the Fourth Excavation Season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga1

ANNALS OF THE NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM 34/1 • 2013 • (p. 3–14) PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FOURTH EXCAVATION SEASON OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXPEDITION TO WAD BEN NAGA1 Pavel Onderka2 ABSTRACT: During its fourth excavation season, the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga focused on the continued exploration of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), where fragments of the Bes-pillars known from descriptions and drawings of early European and American visitors to the site were discovered. Furthermore, fragments of the Lepsius’ Altar B with bilingual names of Queen Amanitore (and King Natakamani) were unearthed. KEY WORDS: Wad Ben Naga – Nubia – Meroitic culture – Meroitic architecture – Meroitic script Expedition The fourth excavation season of the Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga took place between 12 February and 23 March 2012. The mission was headed by Dr. Pavel Onderka (director) and Mohamed Saad Abdalla Saad (inspector of the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums). The works of the fourth season focused on continuing the excavations of the so-called Typhonium (WBN 200), a temple structure located in the western part of Central Wad Ben Naga, which had begun during the third excavation season (cf. Onderka 2011). Further tasks were mainly concerned with site management. No conservation projects took place. The season was carried out under the guidelines for 1 This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic (DKRVO 2012, National Museum, 00023272). The Archaeological Expedition to Wad Ben Naga wishes to express its sincerest thanks and gratitude to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums (Dr. Hassan Hussein Idris and Dr. -

The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1St Cataract Middle Kingdom Forts

SUDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 ASWAN 1st cataract Middle Kingdom forts Egypt RED SEA W a d i el- A lla qi 2nd cataract W a d i G a Selima Oasis b Sai g a b a 3rd cataract ABU HAMED e Sudan il N Kurgus El-Ga’ab Kawa Basin Jebel Barkal 4th cataract 5th cataract el-Kurru Dangeil Debba-Dam Berber ED-DEBBA survey ATBARA ar Ganati ow i H Wad Meroe Hamadab A tb a r m a k a Muweis li e d M d el- a Wad ben Naqa i q ad th W u 6 cataract M i d a W OMDURMAN Wadi Muqaddam KHARTOUM KASSALA survey B lu e Eritrea N i le MODERN TOWNS Ancient sites WAD MEDANI W h it e N i GEDAREF le Jebel Moya KOSTI SENNAR N Ethiopia South 0 250 km Sudan S UDAN & NUBIA The Sudan Archaeological Research Society Bulletin No. 19 2015 Contents The Meroitic Palace and Royal City 80 Kirwan Memorial Lecture Marc Maillot Meroitic royal chronology: the conflict with Rome 2 The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project at Dangeil and its aftermath Satyrs, Rulers, Archers and Pyramids: 88 Janice W. Yelllin A Miscellany from Dangeil 2014-15 Julie R. Anderson, Mahmoud Suliman Bashir Reports and Rihab Khidir elRasheed Middle Stone Age and Early Holocene Archaeology 16 Dangeil: Excavations on Kom K, 2014-15 95 in Central Sudan: The Wadi Muqadam Sébastien Maillot Geoarchaeological Survey The Meroitic Cemetery at Berber. Recent Fieldwork 97 Rob Hosfield, Kevin White and Nick Drake and Discussion on Internal Chronology Newly Discovered Middle Kingdom Forts 30 Mahmoud Suliman Bashir and Romain David in Lower Nubia The Qatar-Sudan Archaeological Project – Archaeology 106 James A. -

Ancient Egyptian Chronology.Pdf

Ancient Egyptian Chronology HANDBOOK OF ORIENTAL STUDIES SECTION ONE THE NEAR AND MIDDLE EAST Ancient Near East Editor-in-Chief W. H. van Soldt Editors G. Beckman • C. Leitz • B. A. Levine P. Michalowski • P. Miglus Middle East R. S. O’Fahey • C. H. M. Versteegh VOLUME EIGHTY-THREE Ancient Egyptian Chronology Edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2006 This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ancient Egyptian chronology / edited by Erik Hornung, Rolf Krauss, and David A. Warburton; with the assistance of Marianne Eaton-Krauss. p. cm. — (Handbook of Oriental studies. Section 1, The Near and Middle East ; v. 83) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-90-04-11385-5 ISBN-10: 90-04-11385-1 1. Egypt—History—To 332 B.C.—Chronology. 2. Chronology, Egyptian. 3. Egypt—Antiquities. I. Hornung, Erik. II. Krauss, Rolf. III. Warburton, David. IV. Eaton-Krauss, Marianne. DT83.A6564 2006 932.002'02—dc22 2006049915 ISSN 0169-9423 ISBN-10 90 04 11385 1 ISBN-13 978 90 04 11385 5 © Copyright 2006 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Applying a Multi- Analytical Approach to the Investigation of Ancient Egyptian Influence in Nubian Communities: The Socio- Cultural Implications of Chemical Variation in Ceramic Styles Julia Carrano Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Stuart T. Smith Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara George Herbst Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Gary H. Girty Department of Geological Sciences, San Diego State University Carl J. Carrano Department of Chemistry, San Diego State University Jeffrey R. Ferguson Archaeometry Laboratory, Research Reactor Center, University of Missouri Abstract is article reviews published archaeological research that explores the potential of combined chemical and petrographic analyses to distin - guish manufacturing methods of ceramics made om Nile river silt. e methodology was initially applied to distinguish the production methods of Egyptian and Nubian- style vessels found in New Kingdom and Napatan Period Egyptian colonial centers in Upper Nubia. Conducted in the context of ongoing excavations and surveys at the third cataract, ceramic characterization can be used to explore the dynamic role pottery production may have played in Egyptian efforts to integrate with or alter native Nubian culture. Results reveal that, despite overall similar geochemistry, x-ray fluorescence (XRF), instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA), and petrography can dis - tinguish Egyptian and Nubian- -

Charles Bonnet Translated by Annie Grant

Charles Bonnet KERMA · PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE 2001-2002 AND 2002-2003 translated by Annie Grant SEASONS Once again we are able to report on major discoveries made at the site of Kerma. The town is situated in a region that has been densely occupied since ancient times, and is rich in remains that illustrate the evolution of Nubian cultures and its external relations and contri- butions. The expansion of cultivation and urbanisation threaten this extraordinary heritage that we have for many years worked to protect. Our research on the origins of Sudanese history has attracted a great deal of interest, and protecting and bringing to light these monuments remain priorities. Several publications have completed the work in the field1, and have been the source of fruitful exchanges with our international colleagues. The discovery on 11 January 2003 of a deposit of monumental statues was an exceptional event for Sudanese archæology and a fortiori for our Mission. These sculptures of the great Sudanese kings of the 25th Dynasty are of very fine quality, and shed new light on a period at Doukki Gel about which we previously knew very little. As a result of these finds, the site has gained in importance; it is of further benefit that they can be compared with the cache excavated 80 years ago by G. A. Reisner at the foot of Gebel Barkal, 200 kilo- metres away2. It will doubtless take several years to study and restore these statues; they were deliberately broken, most probably during Psametik II’s destructive raid into Nubia. We must thank the Swiss National Fund for Scientific Research, which regularly awards us a grant, and also the museums of art and history of the town of Geneva. -

A LIFE COURSE APPROACH to HEALTH in the ANCIENT NILE VALLEY by Katie M

A LIFE COURSE APPROACH TO HEALTH IN THE ANCIENT NILE VALLEY by Katie M. Whitmore A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology West Lafayette, Indiana December 2019 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. Michele Buzon, Chair Department of Anthropology Dr. Sherylyn Briller Department of Anthropology Dr. H. Kory Cooper Department of Anthropology Dr. Stuart Tyson Smith Department of Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara Approved by: Dr. Melissa J. Remis 2 Dedicated to my family 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of many individuals and organizations contributed to the completion of this research and thanks are due to all. Financial support for this research was made possible through the Purdue University Research Foundation Grant, the Department of Anthropology at Purdue University, and the Humanities Without Walls Grand Research Challenge: “The Work of the Humanities in a Changing Climate”. Foremost, I would like to thank my advisor Dr. Michele Buzon. Her support throughout my PhD was invaluable to my progression as a researcher, as a scholar, and the completion of this dissertation. She supported me in various ways as my path took me in new and different directions. Her assistance and contributions go beyond what can be stated here. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Drs. Sherri Briller, Kory Cooper, and Stuart Tyson Smith for their excellent mentorship and support, which greatly contributed to a well-rounded dissertation. During my PhD I spent five wonderful field seasons in Sudan under directors Drs. -

King Aspelta's Vessel Hoard from Nuri in the Sudan

JOURNAL of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston VOL.6, 1994 Fig. I. Pyramids at Nuri, Sudan, before excava- tion; Aspelta’s is the steeply sloped one, just left of the largest pyramid. SUSANNEGANSICKE King Aspelta’s Vessel Hoard from Nuri in the Sudan Introduction A GROUP of exquisite vessels, carved from translucent white stone, is included in the Museum of Fine Arts’s first permanent gallery of ancient Nubian art, which opened in May 1992. All originate from the same archaeological find, the tomb of King Aspelta, who ruled about 600-580 B.C. over the kingdom of Kush (also called Nubia), located along the banks of the Nile in what is today the northern Sudan. The vessels are believed to have contained perfumes or ointments. Five bear the king’s name, and three have his name and additional inscrip- tions. Several are so finely carved as to have almost eggshell-thin sides. One is decorated with a most unusual metal mount, fabricated from gilded silver, which has a curtain of swinging, braided, gold chains hanging from its rim, each suspending a jewel of colored stone. While all of Aspelta’s vessels display ingenious craftsmanship and pose important questions regarding the sources of their materials and places of manufacture, this last one is the most puzzling. The rim with hanging chains, for example, is a type of decoration previ- ously known only outside the Nile Valley on select Greek or Greek- influenced objects. A technical examination, carried out as part of the conservation work necessary to prepare the vessels for display, supplied many new insights into the techniques of their manufacture and clues to their possible origin. -

![Beloved of Amun-Ra, Lord of the Thrones of Two-Lands Who Dwells in Pure-Mountain [I.E., Gebel Barkal]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5688/beloved-of-amun-ra-lord-of-the-thrones-of-two-lands-who-dwells-in-pure-mountain-i-e-gebel-barkal-1475688.webp)

Beloved of Amun-Ra, Lord of the Thrones of Two-Lands Who Dwells in Pure-Mountain [I.E., Gebel Barkal]

1 2 “What is important for a given people is not the fact of being able to claim for itself a more or less grandiose historic past, but rather only of being inhabited by this feeling of continuity of historic consciousness.” - Professor Cheikh Anta DIOP Civilisation ou barbarie, pg. 273 3 4 BELOVED OF AMUN-RA A colossal head of Ramesses II (r. 1279-1213 BCE) is shifted by native workers in the Ramesseum THE LOST ORIGINS OF THE ANCIENT NAMES OF THE KINGS OF RWANDA STEWART ADDINGTON SAINT-DAVID © 2019 S. A. Saint-David All rights reserved. 5 A stele of King Harsiotef of Meroë (r. 404-369 BCE),a Kushite devotee of the cult of Amun-Ra, who took on a full set of titles based on those of the Egyptian pharaohs Thirty-fifth regnal year, second month of Winter, 13th day, under the majesty of “Mighty-bull, Who-appears-in-Napata,” “Who-seeks-the-counsel-of-the-gods,” “Subduer, 'Given'-all-the-desert-lands,” “Beloved-son-of-Amun,” Son-of-Ra, Lord of Two-Lands [Egypt], Lord of Appearances, Lord of Performing Rituals, son of Ra of his body, whom he loves, “Horus-son-of-his-father” [i.e., Harsiotef], may he live forever, Beloved of Amun-Ra, lord of the Thrones of Two-Lands Who dwells in Pure-Mountain [i.e., Gebel Barkal]. We [the gods] have given him all life, stability, and dominion, and all health, and all happiness, like Ra, forever. Behold! Amun of Napata, my good father, gave me the land of Nubia from the moment I desired the crown, and his eye looked favorably on me.