King Aspelta's Vessel Hoard from Nuri in the Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

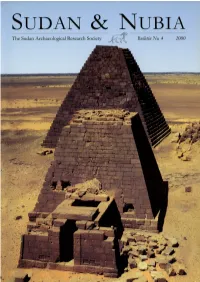

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964)

Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) Lake Nasser, Lower Nubia: photography by the author Degree project in Egyptology/Examensarbete i Egyptologi Carolin Johansson February 2014 Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University Examinator: Dr. Sami Uljas Supervisors: Prof. Irmgard Hein & Dr. Daniel Löwenborg Author: Carolin Johansson, 2014 Svensk titel: Digital rekonstruktion av det arkeologiska landskapet i koncessionsområdet tillhörande den Samnordiska Expeditionen till Sudanska Nubien (1960–1964) English title: Digital Reconstruction of the Archaeological Landscape in the Concession Area of the Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (1961–1964) A Magister thesis in Egyptology, Uppsala University Keywords: Nubia, Geographical Information System (GIS), Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE), digitalisation, digital elevation model. Carolin Johansson, Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, Uppsala University, Box 626 SE-75126 Uppsala, Sweden. Abstract The Scandinavian Joint Expedition to Sudanese Nubia (SJE) was one of the substantial contributions of crucial salvage archaeology within the International Nubian Campaign which was pursued in conjunction with the building of the High Dam at Aswan in the early 1960’s. A large quantity of archaeological data was collected by the SJE in a continuous area of northernmost Sudan and published during the subsequent decades. The present study aimed at transferring the geographical aspects of that data into a digital format thus enabling spatial enquires on the archaeological information to be performed in a computerised manner within a geographical information system (GIS). The landscape of the concession area, which is now completely submerged by the water masses of Lake Nasser, was digitally reconstructed in order to approximate the physical environment which the human societies of ancient Nubia inhabited. -

Nubia: Treasures of Ancient Africa

Audio Guide Transcript Nubia: Treasures of Ancient Africa April 18–August 22, 2021 Main Exhibition Galleries STOP 1 Introduction Gallery: Director’s Welcome Speaker: Brent Benjamin Barbara B. Taylor Director Saint Louis Art Museum Hello, I’m Brent Benjamin, Barbara B. Taylor Director of the Saint Louis Art Museum. It is my pleasure to welcome you to the audio guide for Nubia: Treasures of Ancient Africa. The exhibition presents the history and artistic achievements of ancient Nubia and showcases the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through magnificent jewelry, pottery, sculpture, metalwork, and more. For nearly 3,000 years a series of Nubian kingdoms flourished in the Nile River valley in what is today Sudan. The ancient Nubians controlled vast empires and trade networks and left behind the remains of cities, temples, palaces, and pyramids but few written records. As a result, until recently their story has been told in large part by others—in antiquity by their more famous Egyptian neighbors and rivals, and in the early 20th century by American and European scholars and archaeologists. Through art, this exhibition addresses past misunderstandings and misinterpretations and offers new ways of understanding Nubia’s dynamic history and relevance, which raises issues of power, representation, and cultural bias that were as relevant in past centuries as they are today. This exhibition audio guide offers expert commentaries from Denise Doxey, guest curator of this exhibition and curator of ancient Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The guide features a selection of objects from various ancient Nubian kingdoms and shares insights into the daily life of the Nubians, their aesthetic preferences, religious beliefs, technological inventiveness, and relations with other ancient civilizations. -

Journal of Egyptian Archaeology

Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Past and present members of the staff of the Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Stelae, Reliefs and Paintings, especially R. L. B. Moss and E. W. Burney, have taken part in the analysis of this periodical and the preparation of this list at the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford This pdf version (situation on 14 July 2010): Jaromir Malek (Editor), Diana Magee, Elizabeth Fleming and Alison Hobby (Assistants to the Editor) Naville in JEA I (1914), pl. I cf. 5-8 Abydos. Osireion. vi.29 View. Naville in JEA I (1914), pl. ii [1] Abydos. Osireion. Sloping Passage. vi.30(17)-(18) Osiris and benu-bird from frieze. see Peet in JEA i (1914), 37-39 Abydos. Necropolis. v.61 Account of Cemetery D. see Peet in JEA i (1914), 39 Abydos. Necropolis. Ibis Cemetery. v.77 Description. see Loat in JEA i (1914), 40 and pl. iv Abydos. Necropolis. Ibis Cemetery. v.77 Description and view. Blackman in JEA i (1914), pl. v [1] opp. 42 Meir. Tomb of Pepiankh-h. ir-ib. iv.254 View. Blackman in JEA i (1914), pl. v [2] opp. 42 Meir. Tomb of Pepiankh-h. ir-ib. iv.255(16) Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Stelae, Reliefs and Paintings Griffith Institute, Sackler Library, 1 St John Street, Oxford OX1 2LG, United Kingdom [email protected] 2 Group with calf from 2nd register. Petrie in JEA i (1914), pl. vi cf. 44 El-Riqqa. Finds. iv.87 Part of jewellery, temp. -

"Napatan" Dynasty (From 656 to the Mid-3Rd Cent

CHAPTER SIX THE KINGDOM OF KUSH BETWEEN THE WITHDRAWAL FROM EGYPT AND THE END OF THE "NAPATAN" DYNASTY (FROM 656 TO THE MID-3RD CENT. BC) "Then this god said to His Majesty, 'You shall give me the lands that were taken from me. ,,1 1. THE SOURCES 1.1. Textual evidence From the twenty-nine royal documents in hieroglyphic Egyptian listed in Table A (Ch. II.l.l.l ), seventeen date from the period discussed in this chapter. The monumental inscriptions of Anlamani, Aspelta, Irike Amannote, Harsiyotef and Nastasefi present valuable information on concepts of the myth of the state and the developments in the legiti mation process. They were analysed from these particular aspects as well as from the viewpoint of the structure of Kushite government in earlier chapters in this book (Ch. V.3-5). As documents of political and cultural history, they will be discussed in this chapter, together with the rest of the royal inscriptions preserved from this period, which are, however, fragmentary or pertain to special issues as building or restora tion and economic management of temples. Besides monumental royal documents, there are hieroglyphic texts connected to temple cults and mortuary religion from this period. These will be touched upon in Ch. VI.3.2. The historical evidence is complemented with hieroglyphic Egyptian and Greek documents relating to the Nubian campaign of Psamtik II in 593 BC (Ch. VI.2.1-2), further with Herodotus' remarks on Nubian history and culture (c£ Ch. II.l.2.2) and a number of remarks of varying historical value in works of Greek and Latin 1 Irike-Amannote inscription, Kawa IX, line 60, FHNII No. -

An Ushabti of the King Senkamanisken

Fayoum University Faculty of Archaeology AN USHABTI OF THE KING SENKAMANISKEN Islam I. AMER Faculty of Arts, New Valley University, Egypt E-mail: [email protected] الملخص ABSTRACT يتناول هذا البحث أحد تماثيل اﻷوشابتى التى This article deals with one of ushabtis ترجع للعصر المتأخرو التى وجدت ﻓﻲ السودان . which dates back to the Late period, it was حيث يهدف البحث إلى دراسة تمثال أوشابتى found in Sudan. This paper investigates and studies ushabti of the King للملﻚ " سنﻜاﻣنسﻜﻦ" أحد ﻣلوك ﻣملﻜة كوش بعد Senkamanisken, a king of the kingdom of اﻷسرة الخاﻣسة والعشريﻦ ، والذى عثر ﻓى Kusch who reigned after the Twenty fifth ﻣقبرته بنورى على العديد ﻣﻦ الطرز المختلفة Dynasty. His tomb in Nuri contained many لتماثيل أوشابتى . .of the different types of ushabtis الكلمات الدالة KEYWORDS أوشابتى، نورى، كوش، ﺳﻨكاﻣﻨﺴكﻦ Ushabti, Nuri, Kusch, Senkamanisken INTRODUCTION The excavations of Reisner at Gebel Barkal, Nuri and Meroe (1916, 1919-1923), discovered many archaeological artifacts.1 These include many funerary figures which are known with ushabti from the tombs of kings and queens of Napata. In tomb of the King Senkamanisken2 at Nuri (Nu.3), at least 410 serpentine and 867 faience ushabtis of different types were found.3 Dunham studied the faience ushabti1 and divided them into 1 Dunham published the excavations of Reisner at Gebel Barkal, Nuri and Meroë.:see D. Dunham, The Royal Cemeteries of Kush, Published for the Museum of fine Arts by Harvard university press Cambridge, Vol.II Nuri (1955) 2 The king Senkamanisken (643-623 B.C) one of the kings of Kush, son of Atlanersa (653-643 B.C) see J.U. -

The Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe

The Archaeological Sites of The Island of Meroe Nomination File: World Heritage Centre January 2010 The Republic of the Sudan National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums 0 The Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe Nomination File: World Heritage Centre January 2010 The Republic of the Sudan National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums Preparers: - Dr Salah Mohamed Ahmed - Dr Derek Welsby Preparer (Consultant) Pr. Henry Cleere Team of the “Draft” Management Plan Dr Paul Bidwell Dr. Nick Hodgson Mr. Terry Frain Dr. David Sherlock Management Plan Dr. Sami el-Masri Topographical Work Dr. Mario Santana Quintero Miss Sarah Seranno 1 Contents Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………. 5 1- Identification of the Property………………………………………………… 8 1. a State Party……………………………………………………………………… 8 1. b State, Province, or Region……………………………………………………… 8 1. c Name of Property………………………………………………………………. 8 1. d Geographical coordinates………………………………………………………. 8 1. e Maps and plans showing the boundaries of the nominated site(s) and buffer 9 zones…………………………………………………………………………………… 1. f. Area of nominated properties and proposed buffer zones…………………….. 29 2- Description…………………………………………………………………………. 30 2. a. 1 Description of the nominated properties………………………………........... 30 2. a. 1 General introduction…………………………………………………… 30 2. a. 2 Kushite utilization of the Keraba and Western Boutana……………… 32 2. a. 3 Meroe…………………………………………………………………… 33 2. a. 4 Musawwarat es-Sufra…………………………………………………… 43 2. a. 5 Naqa…………………………………………………………………..... 47 2. b History and development………………………………………………………. 51 2. b. 1 A brief history of the Sudan……………………………………………. 51 2. b. 2 The Kushite civilization and the Island of Meroe……………………… 52 3- Justification for inscription………………………………………………………… 54 …3. a. 1 Proposed statement of outstanding universal value …………………… 54 3. a. 2 Criteria under which inscription is proposed (and justification for 54 inscription under these criteria)………………………………………………………… ..3. -

Mitteilungen Der Sudanarchäologischen Gesellschaft Zu Berlin Mitteilungen Der Sudanarchäologischen A

Der Antike Sudan 2014 Der • Antike Sudan Heft 25 Colour fig. 6: The eastern section of the southeastern square of trench 224.14 with pit [224.14-015] (photograph: Claudia Näser) Heft 25 • 2014 Colour fig. 7: The workplace of the pottery project in the dighouse (photograph: Stephanie Bruck) Mitteilungen der Sudanarchäologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin e.V. Titelbild: Das Nordprofil des Schnittes 102.20 (Foto: Thomas Scheibner) Colour fig. 3: Plane 3 of the northeastern square of trench 2014.14 with Colour fig. 4: The packing of unfired clay [context 224.14- the mudbrick wall [224.14-004] and the lower layer with traces of cir- 003] drawing over the mudbrick wall [224.14-004] (photo- cumscribed burning [224.14-009] (photograph: Claudia Näser) graph: Claudia Näser) Colour fig. 1: Results of the geomagnetic survey in the monastery Colour fig. 5: Selected samples representing seven MGRgroups. Five samples made of wadi clay: AD095 and AD098 (local), AD076 Colour fig. 2: The Musawwarat mosaic 'flower’ bead from the upper foundation layer of wall 120/122 in trench 122.17 and AD105 (local or regional) and AD087 (import). Two samples made of alluvial clay: AD077 and AD081. Samples after refiring at (photograph: Jens Weschenfelder) 1200°C (macrophotos of cross-sections: M. Baranowski) Mitteilungen der Sudanarchäologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin e.V. Heft 25 2014 2014 Inhaltsverzeichnis Editorial ............................................................................................................................................................. -

NOIRS 10'000 Ans D'archéologie En Nubie a Ux Orig in Es

10’000 ans d’archéologie en Nubie en d’archéologie ans 10’000 Aux origines des pharaons noirs Dans la vallée du Nil, au-delà des frontières de l’Empire égyptien, s’étend la Nubie, territoire fascinant et mystérieux, d’où ont émergé les fameux pharaons noirs au 7e siècle av. J.-C. Kerma constitue l’un des centres de cette région, AUX où l’intensité des recherches archéologiques menées par une équipe suisse depuis près de 40 ans a permis de retracer la trajectoire des sociétés antiques au cours des 10’000 dernières années, des premiers établissements séden- taires jusqu’à l’émergence de vastes royaumes qui rivalisèrent avec la puissance des Egyptiens. ORI- L’exposition «Aux origines des pharaons noirs» et le présent catalogue traitent du développe- ment des sociétés préhistoriques et antiques de la Nubie sur le long terme. Plus qu’une simple présentation d’objets illustrant le propos, l’objectif GINES est de restituer l’ambiance du pays et des fouilles archéologiques menées sur le terrain, en combinant les deux sources principales d’infor- mation qui s’offrent à l’archéologue. D’une part le monde des morts et ses impressionnants DES rituels funéraires, d’autre part le monde des vivants, des établissements villageois à la création des premières villes d’Afrique noire. Objets funéraires ou quotidiens, reconstitutions, maquettes, vidéos et présentation du musée de Kerma sont autant de fenêtres qui permettent PHA- de restituer la richesse et la diversité de l’archéo- logie nubienne. RAONS 10’000 ans d’archéologie NOIRS en Nubie 10’000 ans d’archéologie en Nubie AUX ORI- GINES DES PHA- RAONS Matthieu Honegger NOIRS Matthieu Honegger Ouvrage publié à l’occasion de l’exposition présentée au Laténium du 3 septembre 2014 au 17 mai 2015, avec le Aux origines des pharaons noirs, soutien de la Loterie Romande et de l’Association Archéone. -

Aspelta, Beloved of Re'-Harakhty and Tombs in the Temple

SUDAN & NUBIA and the temple extends approximately 120m east-west (Figure QSAP Dangeil 2016: Aspelta, 1). Recent excavations have concentrated on the temple’s peristyle hall. The initial purpose was to expose the proces- Beloved of Re’-Harakhty and sional way and the court around the kiosk and determine if, Tombs in the Temple as with other Amun temples, this route had been flanked by a series of ram statue pairs. In the north-eastern area of the Julie R. Anderson, Rihab Khidir elRasheed court (designated ET8), two statue plinths constructed of red and Mahmoud Suliman Bashir brick and plastered on the exterior with white lime painted yellow, were exposed in autumn 2015. They lay beneath red- brick rubble from the colonnade, architectural fragments Excavations are being conducted within the temenos enclo- from the kiosk, and numerous small sandstone fragments sure of a 1st century AD Amun temple at Dangeil, River Nile from broken ram statues. State, as the Berber-Abidiya Archaeological Mission is focus- In autumn 2016, excavation of this area was expanded ing upon the sacred landscape of the late Kushite period in westward towards the kiosk in the centre of the court. This this region. Recently two field seasons were conducted, one exposed another regularly placed rectangular statue plinth, in autumn 2016 and the other in March 2017.1 The site of the processional way which was paved with red bricks and Dangeil measures approximately 300 x 400m, covers 12ha, sandstone flags, and a sandstone column capital. The plinth and consists of several mounds, some greater than 4m in and area to the west of it were covered with sandstone and height, each covered with fragments of red brick, sandstone, brick tumble from the kiosk and from the destruction of sherds, and white lime plaster. -

Priestess, Queen, Goddess

Solange Ashby Priestess, queen, goddess 2 Priestess, queen, goddess The divine feminine in the kingdom of Kush Solange Ashby The symbol of the kandaka1 – “Nubian Queen” – has been used powerfully in present-day uprisings in Sudan, which toppled the military rule of Omar al-Bashir in 2019 and became a rallying point as the people of Sudan fought for #Sudaxit – a return to African traditions and rule and an ouster of Arab rule and cultural dominance.2 The figure of the kandake continues to reverberate powerfully in the modern Sudanese consciousness. Yet few people outside Sudan or the field of Egyptology are familiar with the figure of the kandake, a title held by some of the queens of Meroe, the final Kushite kingdom in ancient Sudan. When translated as “Nubian Queen,” this title provides an aspirational and descriptive symbol for African women in the diaspora, connoting a woman who is powerful, regal, African. This chapter will provide the historical background of the ruling queens of Kush, a land that many know only through the Bible. Africans appear in the Hebrew Bible, where they are fre- ”which is translated “Ethiopian , יִׁכוש quently referred to by the ethnically generic Hebrew term or “Cushite.” Kush refers to three successive kingdoms located in Nubia, each of which took the name of its capital city: Kerma (2700–1500 BCE), Napata (800–300 BCE), and Meroe (300 BCE–300 CE). Both terms, “Ethiopian” and “Cushite,” were used interchangeably to designate Nubians, Kushites, Ethiopians, or any person from Africa. In Numbers 12:1, Moses’ wife Zipporah is which is translated as either “Ethiopian” or “Cushite” in modern translations of the , יִׁכוש called Bible.3 The Kushite king Taharqo (690–664 BCE), who ruled Egypt as part of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, is mentioned in the Bible as marching against enemies of Israel, the Assyrians (2Kings 19:9, Isa 37:9).