Nubia: Treasures of Ancient Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The eighth-century revolution Version 1.0 December 2005 Ian Morris Stanford University Abstract: Through most of the 20th century classicists saw the 8th century BC as a period of major changes, which they characterized as “revolutionary,” but in the 1990s critics proposed more gradualist interpretations. In this paper I argue that while 30 years of fieldwork and new analyses inevitably require us to modify the framework established by Snodgrass in the 1970s (a profound social and economic depression in the Aegean c. 1100-800 BC; major population growth in the 8th century; social and cultural transformations that established the parameters of classical society), it nevertheless remains the most convincing interpretation of the evidence, and that the idea of an 8th-century revolution remains useful © Ian Morris. [email protected] 1 THE EIGHTH-CENTURY REVOLUTION Ian Morris Introduction In the eighth century BC the communities of central Aegean Greece (see figure 1) and their colonies overseas laid the foundations of the economic, social, and cultural framework that constrained and enabled Greek achievements for the next five hundred years. Rapid population growth promoted warfare, trade, and political centralization all around the Mediterranean. In most regions, the outcome was a concentration of power in the hands of kings, but Aegean Greeks created a new form of identity, the equal male citizen, living freely within a small polis. This vision of the good society was intensely contested throughout the late eighth century, but by the end of the archaic period it had defeated all rival models in the central Aegean, and was spreading through other Greek communities. -

African Journal of History and Culture

OPEN ACCESS African Journal of History and Culture March 2019 ISSN: 2141-6672 DOI: 10.5897/AJHC www.academicjournals.org Editors Pedro A. Fuertes-Olivera Ndlovu Sabelo University of Valladolid Ferguson Centre for African and Asian Studies, E.U.E. Empresariales ABOUTOpen University, AJHC Milton Keynes, Paseo del Prado de la Magdalena s/n United Kingdom. 47005 Valladolid Spain. Biodun J. Ogundayo, PH.D The African Journal of History and Culture (AJHC) is published monthly (one volume per year) by University of Pittsburgh at Bradford Academic Journals. Brenda F. McGadney, Ph.D. 300 Campus Drive School of Social Work, Bradford, Pa 16701 University of Windsor, USA. Canada. African Journal of History and Culture (AJHC) is an open access journal that provides rapid publication Julius O. Adekunle (monthly) of articles in all areas of the subject. TheRonen Journal A. Cohenwelcomes Ph.D. the submission of manuscripts Department of History and Anthropology that meet the general criteria of significance andDepartment scientific of excellence.Middle Eastern Papers and will be published Monmouth University Israel Studies / Political Science, shortlyWest Long after Branch, acceptance. NJ 07764 All articles published in AJHC are peer-reviewed. Ariel University Center, USA. Ariel, 40700, Percyslage Chigora Israel. Department Chair and Lecturer Dept of History and Development Studies Midlands State University ContactZimbabwe Us Private Bag 9055, Gweru, Zimbabwe. Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/AJHC Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/. Editorial Board Dr. Antonio J. Monroy Antón Dr Jephias Mapuva Department of Business Economics African Centre for Citizenship and Democracy Universidad Carlos III , [ACCEDE];School of Government; University of the Western Cape, Madrid, Spain. -

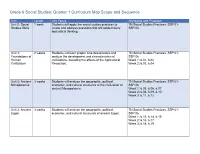

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence Unit Length Unit Focus Standards and Practices Unit 0: Social 1 week Students will apply the social studies practices to TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Studies Skills create and address questions that will guide inquiry SSP.06 and critical thinking. Unit 1: 2 weeks Students will learn proper time designations and TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Foundations of analyze the development and characteristics of SSP.06 Human civilizations, including the effects of the Agricultural Week 1: 6.01, 6.02 Civilization Revolution. Week 2: 6.03, 6.04 Unit 2: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Mesopotamia economic, and cultural structures of the civilization of SSP.06 ancient Mesopotamia. Week 1: 6.05, 6.06, 6.07 Week 2: 6.08, 6.09, 6.10 Week 3: 6.11, 6.12 Unit 3: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Egypt economic, and cultural structures of ancient Egypt. SSP.06 Week 1: 6.13, 6.14, 6.15 Week 2: 6.16, 6.17 Week 3: 6.18, 6.19 Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Map Instructional Framework Course Description: World History and Geography: Early Civilizations Through the Fall of the Western Roman Empire Sixth grade students will study the beginnings of early civilizations through the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Students will analyze the cultural, economic, geographical, historical, and political foundations for early civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel, India, China, Greece, and Rome. -

Egyptian Interest in the Oases in the New Kingdom and a New Stela for Seth from Mut El-Kharab

Egyptian Interest in the Oases in the New Kingdom and a New Stela for Seth from Mut el-Kharab Colin Hope and Olaf Kaper The study of ancient interaction between Egypt and the occupants of regions to the west has focused, quite understandably, upon the major confrontations with the groups now regularly referred to as Liby- ans from the time of Seti I to Ramesses III, and the impact these had upon Egyptian society.1 The situ- ation in the oases of the Western Desert and the role they might have played during these conflicts has not received, until recently, much attention, largely because of the paucity of information either from the Nile Valley or the oases themselves. Yet, given their strategic location, it is not unrealistic to imagine that their control would have been of importance to Egypt both during the confrontations and in the period thereafter. In this short study we present a summary of recently discovered material that contributes sig- nificantly to this question, with a focus upon discoveries made at Mut el-Kharab since excavations com- menced there in 001,3 and a more detailed discussion of one object, a new stela with a hymn dedicated to Seth, which is the earliest attestation of his veneration at the site. We hope that the comments will be of interest to the scholar to whom this volume is dedicated; they are offered with respect, in light of the major contribution he has made to Ramesside studies, and with thanks for his dedication as a teacher and generosity as a colleague. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

Title 'Expanding the History of the Just

Title ‘Expanding the History of the Just War: The Ethics of War in Ancient Egypt.’ Abstract This article expands our understanding of the historical development of just war thought by offering the first detailed analysis of the ethics of war in ancient Egypt. It revises the standard history of the just war tradition by demonstrating that just war thought developed beyond the boundaries of Europe and existed many centuries earlier than the advent of Christianity or even the emergence of Greco-Roman thought on the relationship between war and justice. It also suggests that the creation of a prepotent ius ad bellum doctrine in ancient Egypt, based on universal and absolutist claims to justice, hindered the development of ius in bello norms in Egyptian warfare. It is posited that this development prefigures similar developments in certain later Western and Near Eastern doctrines of just war and holy war. Acknowledgements My thanks to Anthony Lang, Jr. and Cian O’Driscoll for their insightful and instructive comments on an early draft of this article. My thanks also to the three anonymous reviewers and the editorial team at ISQ for their detailed feedback in preparing the article for publication. A version of this article was presented at the Stockholm Centre for the Ethics of War and Peace (June 2016), and I express my gratitude to all the participants for their feedback. James Turner Johnson (1981; 1984; 1999; 2011) has long stressed the importance of a historical understanding of the just war tradition. An increasing body of work draws our attention to the pre-Christian origins of just war thought.1 Nonetheless, scholars and politicians continue to overdraw the association between Christian political theology and the advent of just war thought (O’Driscoll 2015, 1). -

Sphinx Sphinx

SPHINX SPHINX History of a Monument CHRISTIANE ZIVIE-COCHE translated from the French by DAVID LORTON Cornell University Press Ithaca & London Original French edition, Sphinx! Le Pen la Terreur: Histoire d'une Statue, copyright © 1997 by Editions Noesis, Paris. All Rights Reserved. English translation copyright © 2002 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2002 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zivie-Coche, Christiane. Sphinx : history of a moument / Christiane Zivie-Coche ; translated from the French By David Lorton. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8014-3962-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Great Sphinx (Egypt)—History. I.Tide. DT62.S7 Z58 2002 932—dc2i 2002005494 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materi als include vegetable-based, low-VOC inks and acid-free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine-free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further informa tion, visit our website at www.cornellpress.cornell.edu. Cloth printing 10 987654321 TO YOU PIEDRA en la piedra, el hombre, donde estuvo? —Canto general, Pablo Neruda Contents Acknowledgments ix Translator's Note xi Chronology xiii Introduction I 1. Sphinx—Sphinxes 4 The Hybrid Nature of the Sphinx The Word Sphinx 2. -

Domestic Religious Practices

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Domestic religious practices Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7s07628w Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Stevens, Anna Publication Date 2009-12-21 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California DOMESTIC RELIGIOUS PRACTICES الممارسات الدينية المنزلية Anna Stevens EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor Area Editor Religion University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor University of Oxford JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Stevens 2009, Domestic Religious Practices. UEE. Full Citation: Stevens, Anna, 2009, Domestic Religious Practices. In Willeke Wendrich and Jacco Dieleman (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz001nf63v 1010 Version 1, December 2009 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz001nf63v DOMESTIC RELIGIOUS PRACTICES الممارسات الدينية المنزلية Anna Stevens Religion im Alltag Pratiques religieuses privées Domestic religious practices—that is, religious conduct within a household setting—provided an outlet especially for expressing and addressing the concerns of everyday life. They can be traced throughout Egyptian dynastic history, in textual sources such as spells of healing and protection, offering and dedicatory texts, and private letters, and in cult emplacements and objects from settlement sites. Protective divinities such as Bes, Taweret, and Hathor were favored, along with ancestors who could be deceased kin, local elite, or royalty. State-level deities were also supplicated. Central practices were offering and libation, and conducting rites of protection and healing, while there was also strong recourse to protective imagery. -

Charles Bonnet Translated by Annie Grant

Charles Bonnet KERMA · PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE 2001-2002 AND 2002-2003 translated by Annie Grant SEASONS Once again we are able to report on major discoveries made at the site of Kerma. The town is situated in a region that has been densely occupied since ancient times, and is rich in remains that illustrate the evolution of Nubian cultures and its external relations and contri- butions. The expansion of cultivation and urbanisation threaten this extraordinary heritage that we have for many years worked to protect. Our research on the origins of Sudanese history has attracted a great deal of interest, and protecting and bringing to light these monuments remain priorities. Several publications have completed the work in the field1, and have been the source of fruitful exchanges with our international colleagues. The discovery on 11 January 2003 of a deposit of monumental statues was an exceptional event for Sudanese archæology and a fortiori for our Mission. These sculptures of the great Sudanese kings of the 25th Dynasty are of very fine quality, and shed new light on a period at Doukki Gel about which we previously knew very little. As a result of these finds, the site has gained in importance; it is of further benefit that they can be compared with the cache excavated 80 years ago by G. A. Reisner at the foot of Gebel Barkal, 200 kilo- metres away2. It will doubtless take several years to study and restore these statues; they were deliberately broken, most probably during Psametik II’s destructive raid into Nubia. We must thank the Swiss National Fund for Scientific Research, which regularly awards us a grant, and also the museums of art and history of the town of Geneva. -

Kush Under the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (C. 760-656 Bc)

CHAPTER FOUR KUSH UNDER THE TWENTY-FIFTH DYNASTY (C. 760-656 BC) "(And from that time on) the southerners have been sailing northwards, the northerners southwards, to the place where His Majesty is, with every good thing of South-land and every kind of provision of North-land." 1 1. THE SOURCES 1.1. Textual evidence The names of Alara's (see Ch. 111.4.1) successor on the throne of the united kingdom of Kush, Kashta, and of Alara's and Kashta's descen dants (cf. Appendix) Piye,2 Shabaqo, Shebitqo, Taharqo,3 and Tan wetamani are recorded in Ancient History as kings of Egypt and the c. one century of their reign in Egypt is referred to as the period of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.4 While the political and cultural history of Kush 1 DS ofTanwetamani, lines 4lf. (c. 664 BC), FHNI No. 29, trans!. R.H. Pierce. 2 In earlier literature: Piankhy; occasionally: Py. For the reading of the Kushite name as Piye: Priese 1968 24f. The name written as Pyl: W. Spiegelberg: Aus der Geschichte vom Zauberer Ne-nefer-ke-Sokar, Demotischer Papyrus Berlin 13640. in: Studies Presented to F.Ll. Griffith. London 1932 I 71-180 (Ptolemaic). 3 In this book the writing of the names Shabaqo, Shebitqo, and Taharqo (instead of the conventional Shabaka, Shebitku, Taharka/Taharqa) follows the theoretical recon struction of the Kushite name forms, cf. Priese 1978. 4 The Dynasty may also be termed "Nubian", "Ethiopian", or "Kushite". O'Connor 1983 184; Kitchen 1986 Table 4 counts to the Dynasty the rulers from Alara to Tanwetamani.