A Note Towards Quantifying the Medieval Nubian Diaspora

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Journal of History and Culture

OPEN ACCESS African Journal of History and Culture March 2019 ISSN: 2141-6672 DOI: 10.5897/AJHC www.academicjournals.org Editors Pedro A. Fuertes-Olivera Ndlovu Sabelo University of Valladolid Ferguson Centre for African and Asian Studies, E.U.E. Empresariales ABOUTOpen University, AJHC Milton Keynes, Paseo del Prado de la Magdalena s/n United Kingdom. 47005 Valladolid Spain. Biodun J. Ogundayo, PH.D The African Journal of History and Culture (AJHC) is published monthly (one volume per year) by University of Pittsburgh at Bradford Academic Journals. Brenda F. McGadney, Ph.D. 300 Campus Drive School of Social Work, Bradford, Pa 16701 University of Windsor, USA. Canada. African Journal of History and Culture (AJHC) is an open access journal that provides rapid publication Julius O. Adekunle (monthly) of articles in all areas of the subject. TheRonen Journal A. Cohenwelcomes Ph.D. the submission of manuscripts Department of History and Anthropology that meet the general criteria of significance andDepartment scientific of excellence.Middle Eastern Papers and will be published Monmouth University Israel Studies / Political Science, shortlyWest Long after Branch, acceptance. NJ 07764 All articles published in AJHC are peer-reviewed. Ariel University Center, USA. Ariel, 40700, Percyslage Chigora Israel. Department Chair and Lecturer Dept of History and Development Studies Midlands State University ContactZimbabwe Us Private Bag 9055, Gweru, Zimbabwe. Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/AJHC Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/. Editorial Board Dr. Antonio J. Monroy Antón Dr Jephias Mapuva Department of Business Economics African Centre for Citizenship and Democracy Universidad Carlos III , [ACCEDE];School of Government; University of the Western Cape, Madrid, Spain. -

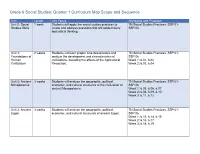

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence Unit Length Unit Focus Standards and Practices Unit 0: Social 1 week Students will apply the social studies practices to TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Studies Skills create and address questions that will guide inquiry SSP.06 and critical thinking. Unit 1: 2 weeks Students will learn proper time designations and TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Foundations of analyze the development and characteristics of SSP.06 Human civilizations, including the effects of the Agricultural Week 1: 6.01, 6.02 Civilization Revolution. Week 2: 6.03, 6.04 Unit 2: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Mesopotamia economic, and cultural structures of the civilization of SSP.06 ancient Mesopotamia. Week 1: 6.05, 6.06, 6.07 Week 2: 6.08, 6.09, 6.10 Week 3: 6.11, 6.12 Unit 3: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Egypt economic, and cultural structures of ancient Egypt. SSP.06 Week 1: 6.13, 6.14, 6.15 Week 2: 6.16, 6.17 Week 3: 6.18, 6.19 Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Map Instructional Framework Course Description: World History and Geography: Early Civilizations Through the Fall of the Western Roman Empire Sixth grade students will study the beginnings of early civilizations through the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Students will analyze the cultural, economic, geographical, historical, and political foundations for early civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel, India, China, Greece, and Rome. -

Religiosita E Societa in Valdelsa · Nel Basso Medioevo

BIBLIOTECA DELLA « MISCELLANEA STORICA DELLA VALDELSA » DIRETTA DA SERGIO GENSINI N. 3 RELIGIOSITA E SOCIETA IN VALDELSA · NEL BASSO MEDIOEVO ATTI DEL CONVEGNO DI S. VIVALDO 29 Settembre 1979 SOCIETÀ STORICA DELLA VALDELSA 1980 I ·I In copertina: S. Vivaldo, Cappelle del sec. XVI. • BIBLIOTECA DELLA « MISCELLANEA STORICA DELLA VALDELSA » DIRETTA DA SERGIO GENSINI N. 3 RELIGIOSITA E SOCIETA IN VALDELSA NEL BASSO MEDIOEVO ATTI DEL CONVEGNO DI S. VIVALDO 29 Settembre 1979 SOCIETÀ STORICA DELLA VALDELSA 1980 Per rendere più spedita la lettura e dare alle relazioni il rilievo che meritano, si sono omesse le consuete « formule ,. che ricorrono durante lo svolgimento di un convegno. PRESENTAZIONE La pubblicazione degli atti del convegno di studi storico-religiosi organizzato in San Vivaldo dalla Società storica della Val d'Elsa ripro pone alcune considerazioni che già venivano alla mente partecipando al l'intensa giornata di ascolto e di dibattito. Significativo è stato l'instaurarsi, nel corso di quel convegno, di un amichevole dialogo fra insigni Maestri, giovani collaboratori dell'inse gnamento universitario, e studenti ancora impegnati nei loro studi; al trettanto ricca di significato è stata la partecipazione di studiosi non italiani, i quali hanno comunicato i risultati delle loro già lunghe ricer che sugli aspetti più diversi della storia delle popolazioni di questa terra toscana, rinnovando ancora una volta lo scambio di esperienze storiografiche che, con particolare efficacia negli ultimi decenni, ha fatto progredire notevolmente -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

The Italian Mandeville

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/91215 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Mandeville in Italy: the Italian Version of the Book of John Mandeville and its Reception (c. 1388-1600) Matthew Coneys Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Italian Studies University of Warwick, School of Modern Languages and Cultures October 2016 Table of Contents Table of figures ................................................................................................................ iv Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................ v Summary .......................................................................................................................... vi Conventions .................................................................................................................... vii Abbreviations ................................................................................................................. viii Introduction ................................................................................................................. -

Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530

PALPABLE POLITICS AND EMBODIED PASSIONS: TERRACOTTA TABLEAU SCULPTURE IN ITALY, 1450-1530 by Betsy Bennett Purvis A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Art University of Toronto ©Copyright by Betsy Bennett Purvis 2012 Palpable Politics and Embodied Passions: Terracotta Tableau Sculpture in Italy, 1450-1530 Doctorate of Philosophy 2012 Betsy Bennett Purvis Department of Art University of Toronto ABSTRACT Polychrome terracotta tableau sculpture is one of the most unique genres of 15th- century Italian Renaissance sculpture. In particular, Lamentation tableaux by Niccolò dell’Arca and Guido Mazzoni, with their intense sense of realism and expressive pathos, are among the most potent representatives of the Renaissance fascination with life-like imagery and its use as a powerful means of conveying psychologically and emotionally moving narratives. This dissertation examines the versatility of terracotta within the artistic economy of Italian Renaissance sculpture as well as its distinct mimetic qualities and expressive capacities. It casts new light on the historical conditions surrounding the development of the Lamentation tableau and repositions this particular genre of sculpture as a significant form of figurative sculpture, rather than simply an artifact of popular culture. In terms of historical context, this dissertation explores overlooked links between the theme of the Lamentation, the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, codes of chivalric honor and piety, and resurgent crusade rhetoric spurred by the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Reconnected to its religious and political history rooted in medieval forms of Sepulchre devotion, the terracotta Lamentation tableau emerges as a key monument that both ii reflected and directed the cultural and political tensions surrounding East-West relations in later 15th-century Italy. -

Being Arab, Muslim, Sudanese. Reshaping Belongings, Local Practices and State Policies in Sudan After the Separation of South Sudan

Arabité, islamité, ‘soudanité’ Being Arab, Muslim, Sudanese W O R K I N G P A P E R N O . 4 RESHAPING IDENTITY POLITICS Capitalising on Shari‘a Debate in Sudan by Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil December 2020 Being Arab, Muslim, Sudanese. Reshaping belongings, local practices and state policies in Sudan after the separation of South Sudan The project focuses on dynamics of Arabization and Islamization in relation to national identity- building in Sudan through an analysis of the three notions articulation within practical processes and the practices of social actors. The central socio-anthropological approach is based on a micro-scale perspective, while also paying attention to macro-scale phenomena, in particular state policies on citizens’ affiliations to an identity forged from categories of Arabness, Islamity and national integration. The aim of the project, which is rooted in classical works on issues of ethnicity, religion and nationality, is to give renewed impetus to the scientific contribution of the debate on the relations between Arab identity and Islam and the issues at stake in the relationship between State and citizens in an African country in which the colonial legacy and ethno-cultural pluralism have made the objectives of nation-building particularly complex. Founded by the AUF (Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie) as a PCSI (Projet de Coopération Scientifique Inter-Universitaire), the project has four institutional partners: CEDEJ Khartoum, the University of Khartoum, University Paris 8/LAVUE and the Max Planck Institute. Barbara Casciarri (University Paris 8) is the scientific coordinator, Jean-Nicolas Bach (CEDEJ Khartoum) is the project leader and Mohamed A.G. -

Sudan, Performed by the Much Loved Singer Mohamed Wardi

Confluence: 1. the junction of two rivers, especially rivers of approximately equal width; 2. an act or process of merging. Oxford English Dictionary For you oh noble grief For you oh sweet dream For you oh homeland For you oh Nile For you oh night Oh good and beautiful one Oh my charming country (…) Oh Nubian face, Oh Arabic word, Oh Black African tattoo Oh My Charming Country (Ya Baladi Ya Habbob), a poem by Sidahmed Alhardallou written in 1972, which has become one of the most popular songs of Sudan, performed by the much loved singer Mohamed Wardi. It speaks of Sudan as one land, praising the country’s diversity. EQUAL RIGHTS TRUST IN PARTNERSHIP WITH SUDANESE ORGANISATION FOR RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT In Search of Confluence Addressing Discrimination and Inequality in Sudan The Equal Rights Trust Country Report Series: 4 London, October 2014 The Equal Rights Trust is an independent international organisation whose pur- pose is to combat discrimination and promote equality as a fundamental human right and a basic principle of social justice. © October 2014 Equal Rights Trust © Photos: Anwar Awad Ali Elsamani © Cover October 2014 Dafina Gueorguieva Layout: Istvan Fenyvesi PrintedDesign: in Dafinathe UK Gueorguieva by Stroma Ltd ISBN: 978-0-9573458-0-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be translated, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by other means without the prior written permission of the publisher, or a licence for restricted copying from the Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd., UK, or the Copyright Clearance Centre, USA. -

Egypt and Nubia

9 Egypt and Nubia Robert Morkot THE, EGYPTIAN E,MPIRE,IN NUBIA IN THE LATE, BRONZE AGE (t.1550-l 070B CE) Introdu,ct'ion:sef-def,nit'ion an,d. the ,irnperi.ol con.cept in Egypt There can be litde doubt rhat the Egyptian pharaohs and the elite of the New I(ngdom viewed themselvesas rulers of an empire. This universal rule is clearly expressedin royal imagerv and terminology (Grimal f986). The pharaoh is styied asthe "Ruler of all that sun encircles" and from the mid-f 8th Dynasry the tides "I(ing of kings" and "Ruler of the rulers," with the variants "Lion" or "Sun of the Rulers," emphasizepharaoh's preeminence among other monarchs.The imagery of krngship is of the all-conquering heroic ruler subjecting a1lforeign lands.The lcingin human form smiteshis enemies.Or, asthe celestialconqueror in the form of the sphinx, he tramples them under foot. In the reigns of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten this imagery was exrended to the king's wife who became the conqueror of the female enemies of Egypt, appearing like her husbandin both human and sphinx forms (Morkot 1986). The appropriateter- minology also appeared; Queen Tiye became "Mistress of all women" and "Great of terror in the foreign lands." Empire, for the Egyptians,equals force - "all lands are under his feet." This metaphor is graphically expressedin the royal footstools and painted paths decorated \Mith images of bound foreign rulers, crushed by pharaoh as he walked or sar. This imagery and terminologv indicates that the Egyptian attirude to their empire was universally applied irrespective of the peoples or countries. -

Sixth Grade World History and Geography: Early Civilizations Through the Decline of the Roman Empire (5Th Century C.E.)

Sixth Grade World History and Geography: Early Civilizations through the Decline of the Roman Empire (5th century C.E.) Course Description: Sixth grade students will study the beginning of early civilizations through the fall of the Roman Empire. Students will study the geographical, social, economic, and political foundations for early civilizations progressing through the Roman Empire. They will analyze the shift from nomadic societies to agricultural societies. Students will study the development of civilizations, including the areas of Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, China, Ancient Israel, Greece, and Rome. The study of these civilizations will include the impact of geography, early history, cultural development, and economic change. The geographic focus will include the study of physical and political features, economic development and resources, and migration patterns. The sixth grade will conclude with the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. This course will be the first concentrated study of world history and geography and will utilize appropriate informational texts and primary sources. Human Origins in Africa through the Neolithic Age: Students analyze the geographic, political, economic, and social structures of early Africa through the Neolithic Age which led to the development of civilizations. 6.1 Identify sites in Africa where archaeologists and historians have found evidence of the origins of modern human beings and describe what the archaeologists found. (G, H) 6.2 Provide textual evidence that characterizes the nomadic hunter-gatherer societies of the Paleolithic Age (their use of tools and fire, basic hunting weapons, beads and other jewelry). (C, H) 6.3 Explain the importance of the discovery of metallurgy and agriculture. -

University of Birmingham History and Exegesis in the Itinerarium

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal University of Birmingham History and exegesis in the Itinerarium of Bernard the Monk (c.867) Reynolds, Daniel DOI: 10.1553/medievalworlds_no10_2019s252 License: Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs (CC BY-NC-ND) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Reynolds, D 2019, 'History and exegesis in the Itinerarium of Bernard the Monk (c.867)', Medieval Worlds, no. 10, pp. 252-296. https://doi.org/10.1553/medievalworlds_no10_2019s252 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. -

A Handlist of Anglo-‐Latin Hagiography Through the Early Twelfth Century

A HANDLIST OF ANGLO-LATIN HAGIOGRAPHY THROUGH THE EARLY TWELFTH CENTURY (FROM THEODORE OF TARSUS TO WILLIAM OF MALMESBURY) Thomas N. Hall The following list originated as a handout developed for a seminar on Anglo-Saxon Hagiography taught at the University of Notre Dame in Spring 2010. Its aim is to supply a provisional inventory, for classroom purposes, of all major known works of Latin hagiography (primarily saints’ Lives and miracle collections but also select sermons, hymns, and other texts that have saints as their subjects) written in Britain or by native British authors or by authors writing anywhere about British saints, from the time of Archbishop Theodore (602–690) to William of Malmesbury (ca. 1090–ca. 1143). The objective here is not to provide exhaustive bibliographical coverage for every single text and author but to offer a basic orientation to the corpus with the hope of stimulating further work. In most cases, only the best or most recent editions and translations are cited, along with the most important secondary scholarship as it has come to my attention, but scholarship published after 2010 is not included. Also not included are the Lives of eminent churchmen who were never canonized, e.g. Vita Gundulfi, ed. R. M. Thomson (Toronto, 1977). Fuller bibliography for many of these authors and texts can be found in BHL; Compendium Auctorum Latinorum Medii Aevi (500–1500), ed. Michael Lapidge, Gian Carlo Garfagnini, and Claudio Leonardi (Florence, 2003– ); Richard Sharpe’s Handlist of the Latin Writers of Great Britain and Ireland before 1540 (Turnhout, 1997); and in the case of Alcuin, Marie- Hélène Jullien and Françoise Perelman, Clavis Scriptorum Latinorum Medii Aevi.