Section 5 the Cultures of Nubia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Journal of History and Culture

OPEN ACCESS African Journal of History and Culture March 2019 ISSN: 2141-6672 DOI: 10.5897/AJHC www.academicjournals.org Editors Pedro A. Fuertes-Olivera Ndlovu Sabelo University of Valladolid Ferguson Centre for African and Asian Studies, E.U.E. Empresariales ABOUTOpen University, AJHC Milton Keynes, Paseo del Prado de la Magdalena s/n United Kingdom. 47005 Valladolid Spain. Biodun J. Ogundayo, PH.D The African Journal of History and Culture (AJHC) is published monthly (one volume per year) by University of Pittsburgh at Bradford Academic Journals. Brenda F. McGadney, Ph.D. 300 Campus Drive School of Social Work, Bradford, Pa 16701 University of Windsor, USA. Canada. African Journal of History and Culture (AJHC) is an open access journal that provides rapid publication Julius O. Adekunle (monthly) of articles in all areas of the subject. TheRonen Journal A. Cohenwelcomes Ph.D. the submission of manuscripts Department of History and Anthropology that meet the general criteria of significance andDepartment scientific of excellence.Middle Eastern Papers and will be published Monmouth University Israel Studies / Political Science, shortlyWest Long after Branch, acceptance. NJ 07764 All articles published in AJHC are peer-reviewed. Ariel University Center, USA. Ariel, 40700, Percyslage Chigora Israel. Department Chair and Lecturer Dept of History and Development Studies Midlands State University ContactZimbabwe Us Private Bag 9055, Gweru, Zimbabwe. Editorial Office: [email protected] Help Desk: [email protected] Website: http://www.academicjournals.org/journal/AJHC Submit manuscript online http://ms.academicjournals.me/. Editorial Board Dr. Antonio J. Monroy Antón Dr Jephias Mapuva Department of Business Economics African Centre for Citizenship and Democracy Universidad Carlos III , [ACCEDE];School of Government; University of the Western Cape, Madrid, Spain. -

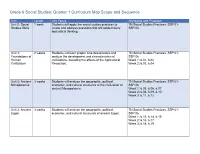

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence Unit Length Unit Focus Standards and Practices Unit 0: Social 1 week Students will apply the social studies practices to TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Studies Skills create and address questions that will guide inquiry SSP.06 and critical thinking. Unit 1: 2 weeks Students will learn proper time designations and TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Foundations of analyze the development and characteristics of SSP.06 Human civilizations, including the effects of the Agricultural Week 1: 6.01, 6.02 Civilization Revolution. Week 2: 6.03, 6.04 Unit 2: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Mesopotamia economic, and cultural structures of the civilization of SSP.06 ancient Mesopotamia. Week 1: 6.05, 6.06, 6.07 Week 2: 6.08, 6.09, 6.10 Week 3: 6.11, 6.12 Unit 3: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Egypt economic, and cultural structures of ancient Egypt. SSP.06 Week 1: 6.13, 6.14, 6.15 Week 2: 6.16, 6.17 Week 3: 6.18, 6.19 Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Map Instructional Framework Course Description: World History and Geography: Early Civilizations Through the Fall of the Western Roman Empire Sixth grade students will study the beginnings of early civilizations through the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Students will analyze the cultural, economic, geographical, historical, and political foundations for early civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel, India, China, Greece, and Rome. -

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum

Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators this is max size of image at 200 dpi; the sil is low res and for the comp only. if approved, needs to be redone carefully American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs Treasures of Egyptian Art from The British Museum Resource for Educators American Federation of Arts © 2006 American Federation of Arts Temples and Tombs: Treasures of Egyptian Art from the British Museum is organized by the American Federation of Arts and The British Museum. All materials included in this resource may be reproduced for educational American Federation of Arts purposes. 212.988.7700 800.232.0270 The AFA is a nonprofit institution that organizes art exhibitions for presen- www.afaweb.org tation in museums around the world, publishes exhibition catalogues, and interim address: develops education programs. 122 East 42nd Street, Suite 1514 New York, NY 10168 after April 1, 2007: 305 East 47th Street New York, NY 10017 Please direct questions about this resource to: Suzanne Elder Burke Director of Education American Federation of Arts 212.988.7700 x26 [email protected] Exhibition Itinerary to Date Oklahoma City Museum of Art Oklahoma City, Oklahoma September 7–November 26, 2006 The Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens Jacksonville, Florida December 22, 2006–March 18, 2007 North Carolina Museum of Art Raleigh, North Carolina April 15–July 8, 2007 Albuquerque Museum of Art and History Albuquerque, New Mexico November 16, 2007–February 10, 2008 Fresno Metropolitan Museum of Art, History and Science Fresno, California March 7–June 1, 2008 Design/Production: Susan E. -

Sudan a Country Study.Pdf

A Country Study: Sudan An Nilain Mosque, at the site of the confluence of the Blue Nile and White Nile in Khartoum Federal Research Division Library of Congress Edited by Helen Chapin Metz Research Completed June 1991 Table of Contents Foreword Acknowledgements Preface Country Profile Country Geography Society Economy Transportation Government and Politics National Security Introduction Chapter 1 - Historical Setting (Thomas Ofcansky) Early History Cush Meroe Christian Nubia The Coming of Islam The Arabs The Decline of Christian Nubia The Rule of the Kashif The Funj The Fur The Turkiyah, 1821-85 The Mahdiyah, 1884-98 The Khalifa Reconquest of Sudan The Anglo-Egyptian Condominium, 1899-1955 Britain's Southern Policy Rise of Sudanese Nationalism The Road to Independence The South and the Unity of Sudan Independent Sudan The Politics of Independence The Abbud Military Government, 1958-64 Return to Civilian Rule, 1964-69 The Nimeiri Era, 1969-85 Revolutionary Command Council The Southern Problem Political Developments National Reconciliation The Transitional Military Council Sadiq Al Mahdi and Coalition Governments Chapter 2 - The Society and its Environment (Robert O. Collins) Physical Setting Geographical Regions Soils Hydrology Climate Population Ethnicity Language Ethnic Groups The Muslim Peoples Non-Muslim Peoples Migration Regionalism and Ethnicity The Social Order Northern Arabized Communities Southern Communities Urban and National Elites Women and the Family Religious -

A Note Towards Quantifying the Medieval Nubian Diaspora

23 A Note towards Quantifying the Medieval Nubian Diaspora Adam Simmons Throughout the Christian medieval period of the kingdoms of Nu- bia (c. sixth–fifteenth centuries), ideas, goods, and peoples traversed vast distances. Judging from primarily external sources, the Nubian diaspora has seldom been thought of as vast, whether in number or geographical scope, both in terms of the relocated and a non- permanently domiciled diaspora. Prior to the Christianisation of the kingdoms of Nobadia, Makuria, and Alwa in the sixth century, likely Nubian delegations, consisting of “Ethiopes,” were received in both Rome and Constantinople alongside ones from neighbouring peoples, such as the Blemmyes and Aksumites. Yet, medieval Nubia is more often seen as inclusive rather than diasporic. This brief dis- cussion will further show that Nubians were an interactive society within the wider Mediterranean, a topic most commonly seen in the debate on Nubian trade.1 Above all, it argues that Nubians had a long relationship with Mediterranean societies that has primarily been overlooked in scholarship. Whilst the evidence presented here is not aimed to be definitive, it does highlight that Nubia’s Mediterranean connections may even have been more diverse than what Giovan- ni Ruffini argued for in his book Medieval Nubia whilst describing Nubia as a “Mediterranean society in Africa.”2 May we even argue for a more developed thesis of interaction? What about the Nubian societies throughout the Mediterranean who interacted with other communities both spiritually and financially? It will be argued here that these questions should be revisited and have potential to fur- ther expand Ruffini’s Mediterranean thesis. -

Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: an Archaeological Note

Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies Volume 3 Know-Hows and Techniques in Ancient Sudan Article 3 2016 Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note Sebastien Maillot [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/djns Recommended Citation Maillot, Sebastien (2016) "Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note," Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies: Vol. 3 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/djns/vol3/iss1/3 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 41 Two Firing Structures from Ancient Sudan: An Archaeological Note Sébastien Maillot* The Kushite temples of Amun at Dukki Gel1 and Dangeil2 (fig. 1) fea- ture in their precincts large heaps of ash mixed with ceramic coni- cal moulds (or “bread moulds”), which are dumps associated with the production of food offerings for the cult. Excavation of the areas dedicated to these activities resumed in 2013 at both sites, uncover- ing numerous firing and storage features. -

Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign

oi.uchicago.edu STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION * NO.42 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO Thomas A. Holland * Editor with the assistance of Thomas G. Urban oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Internet publication of this work was made possible with the generous support of Misty and Lewis Gruber THE ROAD TO KADESH A HISTORICAL INTERPRETATION OF THE BATTLE RELIEFS OF KING SETY I AT KARNAK SECOND EDITION REVISED WILLIAM J. MURNANE THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO STUDIES IN ANCIENT ORIENTAL CIVILIZATION . NO.42 CHICAGO * ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-63725 ISBN: 0-918986-67-2 ISSN: 0081-7554 The Oriental Institute, Chicago © 1985, 1990 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 1990. Printed in the United States of America. oi.uchicago.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS List of M aps ................................ ................................. ................................. vi Preface to the Second Edition ................................................................................................. vii Preface to the First Edition ................................................................................................. ix List of Bibliographic Abbreviations ..................................... ....................... xi Chapter 1. Egypt's Relations with Hatti From the Amarna Period Down to the Opening of Sety I's Reign ...................................................................... ......................... 1 The Clash of Empires -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Title 'Expanding the History of the Just

Title ‘Expanding the History of the Just War: The Ethics of War in Ancient Egypt.’ Abstract This article expands our understanding of the historical development of just war thought by offering the first detailed analysis of the ethics of war in ancient Egypt. It revises the standard history of the just war tradition by demonstrating that just war thought developed beyond the boundaries of Europe and existed many centuries earlier than the advent of Christianity or even the emergence of Greco-Roman thought on the relationship between war and justice. It also suggests that the creation of a prepotent ius ad bellum doctrine in ancient Egypt, based on universal and absolutist claims to justice, hindered the development of ius in bello norms in Egyptian warfare. It is posited that this development prefigures similar developments in certain later Western and Near Eastern doctrines of just war and holy war. Acknowledgements My thanks to Anthony Lang, Jr. and Cian O’Driscoll for their insightful and instructive comments on an early draft of this article. My thanks also to the three anonymous reviewers and the editorial team at ISQ for their detailed feedback in preparing the article for publication. A version of this article was presented at the Stockholm Centre for the Ethics of War and Peace (June 2016), and I express my gratitude to all the participants for their feedback. James Turner Johnson (1981; 1984; 1999; 2011) has long stressed the importance of a historical understanding of the just war tradition. An increasing body of work draws our attention to the pre-Christian origins of just war thought.1 Nonetheless, scholars and politicians continue to overdraw the association between Christian political theology and the advent of just war thought (O’Driscoll 2015, 1). -

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections

Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections Applying a Multi- Analytical Approach to the Investigation of Ancient Egyptian Influence in Nubian Communities: The Socio- Cultural Implications of Chemical Variation in Ceramic Styles Julia Carrano Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Stuart T. Smith Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara George Herbst Department of Anthropology, University of California— Santa Barbara Gary H. Girty Department of Geological Sciences, San Diego State University Carl J. Carrano Department of Chemistry, San Diego State University Jeffrey R. Ferguson Archaeometry Laboratory, Research Reactor Center, University of Missouri Abstract is article reviews published archaeological research that explores the potential of combined chemical and petrographic analyses to distin - guish manufacturing methods of ceramics made om Nile river silt. e methodology was initially applied to distinguish the production methods of Egyptian and Nubian- style vessels found in New Kingdom and Napatan Period Egyptian colonial centers in Upper Nubia. Conducted in the context of ongoing excavations and surveys at the third cataract, ceramic characterization can be used to explore the dynamic role pottery production may have played in Egyptian efforts to integrate with or alter native Nubian culture. Results reveal that, despite overall similar geochemistry, x-ray fluorescence (XRF), instrumental neutron activation analysis (INAA), and petrography can dis - tinguish Egyptian and Nubian- -

Egypt and Nubia

9 Egypt and Nubia Robert Morkot THE, EGYPTIAN E,MPIRE,IN NUBIA IN THE LATE, BRONZE AGE (t.1550-l 070B CE) Introdu,ct'ion:sef-def,nit'ion an,d. the ,irnperi.ol con.cept in Egypt There can be litde doubt rhat the Egyptian pharaohs and the elite of the New I(ngdom viewed themselvesas rulers of an empire. This universal rule is clearly expressedin royal imagerv and terminology (Grimal f986). The pharaoh is styied asthe "Ruler of all that sun encircles" and from the mid-f 8th Dynasry the tides "I(ing of kings" and "Ruler of the rulers," with the variants "Lion" or "Sun of the Rulers," emphasizepharaoh's preeminence among other monarchs.The imagery of krngship is of the all-conquering heroic ruler subjecting a1lforeign lands.The lcingin human form smiteshis enemies.Or, asthe celestialconqueror in the form of the sphinx, he tramples them under foot. In the reigns of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten this imagery was exrended to the king's wife who became the conqueror of the female enemies of Egypt, appearing like her husbandin both human and sphinx forms (Morkot 1986). The appropriateter- minology also appeared; Queen Tiye became "Mistress of all women" and "Great of terror in the foreign lands." Empire, for the Egyptians,equals force - "all lands are under his feet." This metaphor is graphically expressedin the royal footstools and painted paths decorated \Mith images of bound foreign rulers, crushed by pharaoh as he walked or sar. This imagery and terminologv indicates that the Egyptian attirude to their empire was universally applied irrespective of the peoples or countries. -

CV 2 Purdue Research Foundation Research Grant, Purdue University (Research Assistantship), 2016-2017

Michele Rose Buzon Department of Anthropology Purdue University 700 W. State Street West Lafayette, IN 47907-2059 [email protected] (765) 494-4680 (tel)/(765) 496-7411 (fax) http://web.ics.purdue.edu/~mbuzon tombos.org ACADEMIC POSITIONS Full Professor, Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, 2017-present Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, 2010-2017. Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, 2007-2010. Instructor, Honours Thesis Supervisor, Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary, 2006-2007. Postdoctoral Fellow, Instructor, Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta, 2004-2006. Teaching Associate, Department of Anthropology, UCSB, 2004. Teaching Assistant, Department of Anthropology, UCSB, 2001, 2002. Laboratory Manager, Biological Anthropology Laboratory, Loyola University Chicago, 1996-1998. RESEARCH INTERESTS Bioarchaeology, Paleopathology, Culture Contact, Biological and Ethnic Identity, Environmental Stress, Isotope Analysis, Nubia, Egypt EDUCATION Killam Postdoctoral Fellowship, Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta, 2004-2006. Project: “Strontium Isotope Analysis of Migration in the Nile Valley.” Supervisors: Dr. Nancy Lovell, Dr. Sandra Garvie-Lok. Ph.D. in Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2004. Dissertation: “A Bioarchaeological Perspective on State Formation in the Nile Valley.” Supervisor: Dr. Phillip L. Walker M.A. in Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2000. Supervisor: Dr. Phillip L. Walker B.S. Honors in Anthropology, Magna Cum Laude, Loyola University Chicago, 1996. August 2019 RESEARCH AWARDS Purdue University College of Liberal Arts Discovery Excellence Award, 2018 Purdue University Lu Ann Aday Award, 2017 Purdue University Faculty Scholar, Purdue University, 2014-2019. EXTRAMURAL FUNDING Senior Research Grant, BCS-1916719, National Science Foundation Archaeology ($60,810), 2019-2022. Collaborative Research: Assessing the Impact of Holocene Climate Change on Bioavailable Strontium Within the Nile River Valley.