Egypt and Nubia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth Fonctions Et Usages Du Mythe Égyptien

Revue de l’histoire des religions 4 | 2018 Qu’est-ce qu’un mythe égyptien ? Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth Fonctions et usages du mythe égyptien Katja Goebs and John Baines Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/rhr/9334 DOI: 10.4000/rhr.9334 ISSN: 2105-2573 Publisher Armand Colin Printed version Date of publication: 1 December 2018 Number of pages: 645-681 ISBN: 978-2-200-93200-8 ISSN: 0035-1423 Electronic reference Katja Goebs and John Baines, “Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth”, Revue de l’histoire des religions [Online], 4 | 2018, Online since 01 December 2020, connection on 13 January 2021. URL: http:// journals.openedition.org/rhr/9334 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/rhr.9334 Tous droits réservés KATJA GOEBS / JOHN BAINES University of Toronto / University of Oxford Functions and Uses of Egyptian Myth* This article discusses functions and uses of myth in ancient Egypt as a contribution to comparative research. Applications of myth are reviewed in order to present a basic general typology of usages: from political, scholarly, ritual, and medical applications, through incorporation in images, to linguistic and literary exploitations. In its range of function and use, Egyptian myth is similar to that of other civilizations, except that written narratives appear to have developed relatively late. The many attested forms and uses underscore its flexibility, which has entailed many interpretations starting with assessments of the Osiris myth reported by Plutarch (2nd century AD). Myths conceptualize, describe, explain, and control the world, and they were adapted to an ever-changing reality. Fonctions et usages du mythe égyptien Cet article discute les fonctions et les usages du mythe en Égypte ancienne dans une perspective comparatiste et passe en revue ses applications, afin de proposer une typologie générale de ses usages – applications politiques, érudites, rituelles et médicales, incorporation dans des images, exploitation linguistique et littéraire. -

Enrichment: Nubia and the Conquest of Egypt

ANCIENT EGYPT AND NUBIA SECTION 3 Name ________________________________________________ Class ________________________ Date ______________ Enrichment: Nubia and the Conquest of Egypt Directions Read the selection below. Then answer the questions that follow. Nubian kings already ruled northern Nubia at the time of the earliest Egyptian records around 3000 B.C. The Egyptians of the time called Nubia “Ta Sety,” or the “Land of the Bows,” because Nubian bowmen were famous in the region. In about 1950 B.C., Egypt conquered Nubia (or Kush, as Egyptians of the time called it). In the years that followed, Nubia took on many aspects of Egyptian culture, including the worship of many of the same gods and burial of kings in pyramids. By the 800s B.C., Egypt had become disunited, with foreign rulers in the north. The southern Egyptians asked Nubia for protection. About 750 B.C., the Nubian leader Piye invaded northern Egypt. The entire country was united again, from the capital city Meroë, in Kush, to the Mediterranean Sea. Kushite leaders ruled for the next 100 years. Unlike many leaders who took over foreign lands, Piye did not kill or otherwise punish those he had conquered. Instead, he kept them on to run the government and military forces. He and the men who ruled after him became the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty of Egypt. In about 650 B.C., the Kushites were pushed out of Egypt by the army of the Assyrian empire. Kush remained a powerful kingdom to the south of Egypt for hundreds of years. 1. What did the Egyptians call Nubia when it was under Egyptian rule? 2. -

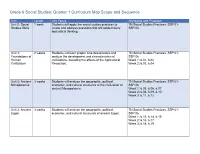

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence

Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Curriculum Map Scope and Sequence Unit Length Unit Focus Standards and Practices Unit 0: Social 1 week Students will apply the social studies practices to TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Studies Skills create and address questions that will guide inquiry SSP.06 and critical thinking. Unit 1: 2 weeks Students will learn proper time designations and TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Foundations of analyze the development and characteristics of SSP.06 Human civilizations, including the effects of the Agricultural Week 1: 6.01, 6.02 Civilization Revolution. Week 2: 6.03, 6.04 Unit 2: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Mesopotamia economic, and cultural structures of the civilization of SSP.06 ancient Mesopotamia. Week 1: 6.05, 6.06, 6.07 Week 2: 6.08, 6.09, 6.10 Week 3: 6.11, 6.12 Unit 3: Ancient 3 weeks Students will analyze the geographic, political, TN Social Studies Practices: SSP.01- Egypt economic, and cultural structures of ancient Egypt. SSP.06 Week 1: 6.13, 6.14, 6.15 Week 2: 6.16, 6.17 Week 3: 6.18, 6.19 Grade 6 Social Studies: Quarter 1 Map Instructional Framework Course Description: World History and Geography: Early Civilizations Through the Fall of the Western Roman Empire Sixth grade students will study the beginnings of early civilizations through the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Students will analyze the cultural, economic, geographical, historical, and political foundations for early civilizations, including Mesopotamia, Egypt, Israel, India, China, Greece, and Rome. -

A Note Towards Quantifying the Medieval Nubian Diaspora

23 A Note towards Quantifying the Medieval Nubian Diaspora Adam Simmons Throughout the Christian medieval period of the kingdoms of Nu- bia (c. sixth–fifteenth centuries), ideas, goods, and peoples traversed vast distances. Judging from primarily external sources, the Nubian diaspora has seldom been thought of as vast, whether in number or geographical scope, both in terms of the relocated and a non- permanently domiciled diaspora. Prior to the Christianisation of the kingdoms of Nobadia, Makuria, and Alwa in the sixth century, likely Nubian delegations, consisting of “Ethiopes,” were received in both Rome and Constantinople alongside ones from neighbouring peoples, such as the Blemmyes and Aksumites. Yet, medieval Nubia is more often seen as inclusive rather than diasporic. This brief dis- cussion will further show that Nubians were an interactive society within the wider Mediterranean, a topic most commonly seen in the debate on Nubian trade.1 Above all, it argues that Nubians had a long relationship with Mediterranean societies that has primarily been overlooked in scholarship. Whilst the evidence presented here is not aimed to be definitive, it does highlight that Nubia’s Mediterranean connections may even have been more diverse than what Giovan- ni Ruffini argued for in his book Medieval Nubia whilst describing Nubia as a “Mediterranean society in Africa.”2 May we even argue for a more developed thesis of interaction? What about the Nubian societies throughout the Mediterranean who interacted with other communities both spiritually and financially? It will be argued here that these questions should be revisited and have potential to fur- ther expand Ruffini’s Mediterranean thesis. -

ROYAL STATUES Including Sphinxes

ROYAL STATUES Including sphinxes EARLY DYNASTIC PERIOD Dynasties I-II Including later commemorative statues Ninutjer 800-150-900 Statuette of Ninuter seated wearing heb-sed cloak, calcite(?), formerly in G. Michaelidis colln., then in J. L. Boele van Hensbroek colln. in 1962. Simpson, W. K. in JEA 42 (1956), 45-9 figs. 1, 2 pl. iv. Send 800-160-900 Statuette of Send kneeling with vases, bronze, probably made during Dyn. XXVI, formerly in G. Posno colln. and in Paris, Hôtel Drouot, in 1883, now in Berlin, Ägyptisches Museum, 8433. Abubakr, Abd el Monem J. Untersuchungen über die ägyptischen Kronen (1937), 27 Taf. 7; Roeder, Äg. Bronzefiguren 292 [355, e] Abb. 373 Taf. 44 [f]; Wildung, Die Rolle ägyptischer Könige im Bewußtsein ihrer Nachwelt i, 51 [Dok. xiii. 60] Abb. iv [1]. Name, Gauthier, Livre des Rois i, 22 [vi]. See Antiquités égyptiennes ... Collection de M. Gustave Posno (1874), No. 53; Hôtel Drouot Sale Cat. May 22-6, 1883, No. 53; Stern in Zeitschrift für die gebildete Welt 3 (1883), 287; Ausf. Verz. 303; von Bissing in 2 Mitteilungen des Kaiserlich Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung xxxviii (1913), 259 n. 2 (suggests from Memphis). Not identified by texts 800-195-000 Head of royal statue, perhaps early Dyn. I, in London, Petrie Museum, 15989. Petrie in Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland xxxvi (1906), 200 pl. xix; id. Arts and Crafts 31 figs. 19, 20; id. The Revolutions of Civilisation 15 fig. 7; id. in Anc. Eg. (1915), 168 view 4; id. in Hammerton, J. A. -

Reading G Uide

1 Reading Guide Introduction Pharaonic Lives (most items are on map on page 10) Bodies of Water Major Regions Royal Cities Gulf of Suez Faiyum Oasis Akhetaten Sea The Levant Alexandria Nile River Libya Avaris Nile cataracts* Lower Egypt Giza Nile Delta Nubia Herakleopolis Magna Red Sea Palestine Hierakonpolis Punt Kerma *Cataracts shown as lines Sinai Memphis across Nile River Syria Sais Upper Egypt Tanis Thebes 2 Chapter 1 Pharaonic Kingship: Evolution & Ideology Myths Time Periods Significant Artifacts Predynastic Origins of Kingship: Naqada Naqada I The Narmer Palette Period Naqada II The Scorpion Macehead Writing History of Maqada III Pharaohs Old Kingdom Significant Buildings Ideology & Insignia of Middle Kingdom Kingship New Kingdom Tombs at Abydos King’s Divinity Mythology Royal Insignia Royal Names & Titles The Book of the Heavenly Atef Crown The Birth Name Cow Blue Crown (Khepresh) The Golden Horus Name The Contending of Horus Diadem (Seshed) The Horus Name & Seth Double Crown (Pa- The Nesu-Bity Name Death & Resurrection of Sekhemty) The Two Ladies Name Osiris Nemes Headdress Red Crown (Desheret) Hem Deities White Crown (Hedjet) Per-aa (The Great House) The Son of Re Horus Bull’s tail Isis Crook Osiris False beard Maat Flail Nut Rearing cobra (uraeus) Re Seth Vocabulary Divine Forces demi-god heka (divine magic) Good God (netjer netjer) hu (divine utterance) Great God (netjer aa) isfet (chaos) ka-spirit (divine energy) maat (divine order) Other Topics Ramesses II making sia (Divine knowledge) an offering to Ra Kings’ power -

Kush Under the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (C. 760-656 Bc)

CHAPTER FOUR KUSH UNDER THE TWENTY-FIFTH DYNASTY (C. 760-656 BC) "(And from that time on) the southerners have been sailing northwards, the northerners southwards, to the place where His Majesty is, with every good thing of South-land and every kind of provision of North-land." 1 1. THE SOURCES 1.1. Textual evidence The names of Alara's (see Ch. 111.4.1) successor on the throne of the united kingdom of Kush, Kashta, and of Alara's and Kashta's descen dants (cf. Appendix) Piye,2 Shabaqo, Shebitqo, Taharqo,3 and Tan wetamani are recorded in Ancient History as kings of Egypt and the c. one century of their reign in Egypt is referred to as the period of the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty.4 While the political and cultural history of Kush 1 DS ofTanwetamani, lines 4lf. (c. 664 BC), FHNI No. 29, trans!. R.H. Pierce. 2 In earlier literature: Piankhy; occasionally: Py. For the reading of the Kushite name as Piye: Priese 1968 24f. The name written as Pyl: W. Spiegelberg: Aus der Geschichte vom Zauberer Ne-nefer-ke-Sokar, Demotischer Papyrus Berlin 13640. in: Studies Presented to F.Ll. Griffith. London 1932 I 71-180 (Ptolemaic). 3 In this book the writing of the names Shabaqo, Shebitqo, and Taharqo (instead of the conventional Shabaka, Shebitku, Taharka/Taharqa) follows the theoretical recon struction of the Kushite name forms, cf. Priese 1978. 4 The Dynasty may also be termed "Nubian", "Ethiopian", or "Kushite". O'Connor 1983 184; Kitchen 1986 Table 4 counts to the Dynasty the rulers from Alara to Tanwetamani. -

CV 2 Purdue Research Foundation Research Grant, Purdue University (Research Assistantship), 2016-2017

Michele Rose Buzon Department of Anthropology Purdue University 700 W. State Street West Lafayette, IN 47907-2059 [email protected] (765) 494-4680 (tel)/(765) 496-7411 (fax) http://web.ics.purdue.edu/~mbuzon tombos.org ACADEMIC POSITIONS Full Professor, Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, 2017-present Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, 2010-2017. Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Purdue University, 2007-2010. Instructor, Honours Thesis Supervisor, Department of Archaeology, University of Calgary, 2006-2007. Postdoctoral Fellow, Instructor, Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta, 2004-2006. Teaching Associate, Department of Anthropology, UCSB, 2004. Teaching Assistant, Department of Anthropology, UCSB, 2001, 2002. Laboratory Manager, Biological Anthropology Laboratory, Loyola University Chicago, 1996-1998. RESEARCH INTERESTS Bioarchaeology, Paleopathology, Culture Contact, Biological and Ethnic Identity, Environmental Stress, Isotope Analysis, Nubia, Egypt EDUCATION Killam Postdoctoral Fellowship, Department of Anthropology, University of Alberta, 2004-2006. Project: “Strontium Isotope Analysis of Migration in the Nile Valley.” Supervisors: Dr. Nancy Lovell, Dr. Sandra Garvie-Lok. Ph.D. in Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2004. Dissertation: “A Bioarchaeological Perspective on State Formation in the Nile Valley.” Supervisor: Dr. Phillip L. Walker M.A. in Anthropology, University of California, Santa Barbara, 2000. Supervisor: Dr. Phillip L. Walker B.S. Honors in Anthropology, Magna Cum Laude, Loyola University Chicago, 1996. August 2019 RESEARCH AWARDS Purdue University College of Liberal Arts Discovery Excellence Award, 2018 Purdue University Lu Ann Aday Award, 2017 Purdue University Faculty Scholar, Purdue University, 2014-2019. EXTRAMURAL FUNDING Senior Research Grant, BCS-1916719, National Science Foundation Archaeology ($60,810), 2019-2022. Collaborative Research: Assessing the Impact of Holocene Climate Change on Bioavailable Strontium Within the Nile River Valley. -

Sixth Grade World History and Geography: Early Civilizations Through the Decline of the Roman Empire (5Th Century C.E.)

Sixth Grade World History and Geography: Early Civilizations through the Decline of the Roman Empire (5th century C.E.) Course Description: Sixth grade students will study the beginning of early civilizations through the fall of the Roman Empire. Students will study the geographical, social, economic, and political foundations for early civilizations progressing through the Roman Empire. They will analyze the shift from nomadic societies to agricultural societies. Students will study the development of civilizations, including the areas of Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, China, Ancient Israel, Greece, and Rome. The study of these civilizations will include the impact of geography, early history, cultural development, and economic change. The geographic focus will include the study of physical and political features, economic development and resources, and migration patterns. The sixth grade will conclude with the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. This course will be the first concentrated study of world history and geography and will utilize appropriate informational texts and primary sources. Human Origins in Africa through the Neolithic Age: Students analyze the geographic, political, economic, and social structures of early Africa through the Neolithic Age which led to the development of civilizations. 6.1 Identify sites in Africa where archaeologists and historians have found evidence of the origins of modern human beings and describe what the archaeologists found. (G, H) 6.2 Provide textual evidence that characterizes the nomadic hunter-gatherer societies of the Paleolithic Age (their use of tools and fire, basic hunting weapons, beads and other jewelry). (C, H) 6.3 Explain the importance of the discovery of metallurgy and agriculture. -

Border Center for Support and Consulting (BSC), Egypt

Border Center for Support and Consulting (BSC) Founded in 2013 https://www.bsc-eg.org BSC (Hodoud) Is An EgyptiAn non-profit humAn rights orgAnizAtion working on the rights of NubiAns As indigenous people within Egypt through the legal and community framework, and focuses its efforts to enable Nubians entitlement as indigenous people within Egypt to enjoy the internAtionAl rights pAckAge estAblished in nAtionAl lAws And internAtionAl obligations, through advocacy programs and raising the capacity and legal assistance through which we submit and propose legislative amendments and the issuance of studies and periodicals corresponding to the international obligations of Egypt. A. Where is Nubia? 1. The geographical region located on the banks of the Nile from the first waterfall south of Egypt and extends to the sixth waterfall in Sudan, the Nubians settled in this region since thousands of years in the form of a group of one ethnic origin joined by one language and distinctive culture richness, which contributed to shaping their habits and the form of their community. 2. The beginning of the Nubian problem in modern times: 3. In 1841, after the Ottoman caliphate1 issued the decree demarcating the southern border of Egypt, this was followed by the decision of the Minister of Interior to amend the borders of Egypt and Sudan on the basis of the bilateral agreement between Egypt and the British occupation on January 19, 1899, which involved the separation of ten Nubian villages of the Halfa Center in Nubia province, villages south of the latitude 22, to enter the borders of Sudan. The area inside the Egyptian border extended from the village of Adhandan in the south to the waterfall in the north, and the name of the province of Nubia, which was known as the Border Directorate, was changed to Aswan. -

Antiguo Oriente

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Peftjauawybast, King of Nen-nesut: genealogy, art history, and the chronology of Late-Libyan Egypt AUTHORS Morkot, RG; James, PJ JOURNAL Antiguo Oriente DEPOSITED IN ORE 14 March 2017 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10871/26545 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication CUADERNOS DEL CENTRO DE ESTUDIOS DE HISTORIA DEL ANTIGUO ORIENTE ANTIGUO ORIENTE Volumen 7 2009 Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires - Argentina Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Departamento de Historia Centro de Estudios de Historia del Antiguo Oriente Av. Alicia Moreau de Justo 1500 P. B. Edificio San Alberto Magno (C1107AFD) Buenos Aires Argentina Sitio Web: www.uca.edu.ar/cehao Dirección electrónica: [email protected] Teléfono: (54-11) 4349-0200 int. 1189 Fax: (54-11) 4338-0791 Antiguo Oriente se encuentra indizada en: BiBIL, University of Lausanne, Suiza. DIALNET, Universidad de La Rioja, España. INIST, Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique, Francia. LATINDEX, Catálogo, México. LIBRARY of CONGRESS, Washington DC, EE.UU. Núcleo Básico de Publicaciones Periódicas Científicas y Tecnológicas Argentinas (CONICET). RAMBI, Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalén, Israel. Hecho el depósito que marca la Ley 11.723 Impreso en la Argentina © 2010 UCA ISSN 1667-9202 AUTORIDADES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA ARGENTINA Rector Monseñor Dr. -

Seismic Anisotropy and the Mantle Dynamics Beneath the Arabian Plate

Scholars' Mine Doctoral Dissertations Student Theses and Dissertations Fall 2018 Seismic anisotropy and the mantle dynamics beneath the Arabian plate Saleh Ismail Hassan Qaysi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/doctoral_dissertations Part of the Geophysics and Seismology Commons Department: Geosciences and Geological and Petroleum Engineering Recommended Citation Qaysi, Saleh Ismail Hassan, "Seismic anisotropy and the mantle dynamics beneath the Arabian plate" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 2727. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/doctoral_dissertations/2727 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEISMIC ANISOTROPY AND THE MANTLE DYNAMICS BENEATH THE ARABIAN PLATE by SALEH ISMAIL HASSAN QAYSI A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the MISSOURI UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS 2018 Approved by: Kelly Liu, Advisor Stephen Gao Neil L. Anderson Ralph Flori Jr Saad Mogren 2018 Saleh Ismail Hassan Qaysi All Rights Reserve iii PUBLICATION DISSERTATION OPTION This dissertation consists of two articles formatted using the publication option. Paper I, the pages from 3 – 19 were accepted for publication in the Seismological Research Letter on December 19, 2018 under number (SRL-D-18-00144_R1). Paper II, the pages from 20 – 56 are in a preparation to be submitted to a scientific journal. iv ABSTRACT We investigate mantle seismic azimuthal anisotropy and deformation beneath the Arabian Plate and adjacent areas using data from 182 broadband seismic stations which include 157 stations managed by the Saudi Geological Survey.