Lecture Transcript: New Perspectives on Ancient Nubia at the Museum Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics The eighth-century revolution Version 1.0 December 2005 Ian Morris Stanford University Abstract: Through most of the 20th century classicists saw the 8th century BC as a period of major changes, which they characterized as “revolutionary,” but in the 1990s critics proposed more gradualist interpretations. In this paper I argue that while 30 years of fieldwork and new analyses inevitably require us to modify the framework established by Snodgrass in the 1970s (a profound social and economic depression in the Aegean c. 1100-800 BC; major population growth in the 8th century; social and cultural transformations that established the parameters of classical society), it nevertheless remains the most convincing interpretation of the evidence, and that the idea of an 8th-century revolution remains useful © Ian Morris. [email protected] 1 THE EIGHTH-CENTURY REVOLUTION Ian Morris Introduction In the eighth century BC the communities of central Aegean Greece (see figure 1) and their colonies overseas laid the foundations of the economic, social, and cultural framework that constrained and enabled Greek achievements for the next five hundred years. Rapid population growth promoted warfare, trade, and political centralization all around the Mediterranean. In most regions, the outcome was a concentration of power in the hands of kings, but Aegean Greeks created a new form of identity, the equal male citizen, living freely within a small polis. This vision of the good society was intensely contested throughout the late eighth century, but by the end of the archaic period it had defeated all rival models in the central Aegean, and was spreading through other Greek communities. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

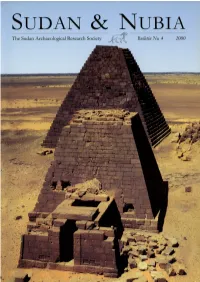

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Separating Fact from Fiction in the Aiolian Migration

hesperia yy (2008) SEPARATING FACT Pages399-430 FROM FICTION IN THE AIOLIAN MIGRATION ABSTRACT Iron Age settlementsin the northeastAegean are usuallyattributed to Aioliancolonists who journeyed across the Aegean from mainland Greece. This articlereviews the literary accounts of the migration and presentsthe relevantarchaeological evidence, with a focuson newmaterial from Troy. No onearea played a dominantrole in colonizing Aiolis, nor is sucha widespread colonizationsupported by the archaeologicalrecord. But the aggressive promotionof migrationaccounts after the PersianWars provedmutually beneficialto bothsides of theAegean and justified the composition of the Delian League. Scholarlyassessments of habitation in thenortheast Aegean during the EarlyIron Age are remarkably consistent: most settlements are attributed toAiolian colonists who had journeyed across the Aegean from Thessaly, Boiotia,Akhaia, or a combinationof all three.1There is no uniformityin theancient sources that deal with the migration, although Orestes and his descendantsare named as theleaders in mostaccounts, and are credited withfounding colonies over a broadgeographic area, including Lesbos, Tenedos,the western and southerncoasts of theTroad, and theregion betweenthe bays of Adramyttion and Smyrna(Fig. 1). In otherwords, mainlandGreece has repeatedly been viewed as theagent responsible for 1. TroyIV, pp. 147-148,248-249; appendixgradually developed into a Mountjoy,Holt Parker,Gabe Pizzorno, Berard1959; Cook 1962,pp. 25-29; magisterialstudy that is includedhere Allison Sterrett,John Wallrodt, Mal- 1973,pp. 360-363;Vanschoonwinkel as a companionarticle (Parker 2008). colm Wiener, and the anonymous 1991,pp. 405-421; Tenger 1999, It is our hope that readersinterested in reviewersfor Hesperia. Most of trie pp. 121-126;Boardman 1999, pp. 23- the Aiolian migrationwill read both articlewas writtenin the Burnham 33; Fisher2000, pp. -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Die Profanarchitektur Der Napatanischen Epoche

2015 Varia Uwe Sievertsen Die Profanarchitektur der napatanischen Epoche Einleitung erscheint, auch der Übergang zur meroitischen Zeit in die Betrachtung einbezogen. In der Zeit vor und um die Mitte des 1. Jts. v. Chr. waren Königtum und gesellschaftliche Eliten im Reich von Kusch nicht nur durch eigenständige Herrscherpaläste kulturelle Traditionen, sondern auch durch viel- fältige Einflüsse aus dem nördlichen Nachbarland Einen Eindruck vom Aussehen kuschitischer Herr- Ägypten geprägt. scherpaläste aus napatanischer Zeit vermittelt bis- Die Anklänge und Entlehnungen lassen sich etwa lang einzig der Palast B. 1200 von Gebel Barkal. in der Schrift, in den Grabsitten sowie in der Rund- Der sogenannte Napatan Palace liegt südwestlich und Reliefplastik, aber ebenso in der architektoni- der beiden parallel ausgerichteten Amuntempel B. schen Hinterlassenschaft beobachten. Dort erstrek- 500 und B. 800 (Abb. 1-2).2 Er beschreibt ein gro- ken sie sich auf die Sakralarchitektur, wie sie uns ßes Rechteck von rund 70 x 45 m Fläche, doch ist beispielhaft in den großen Amuntempeln von Gebel nur die Gebäudegrenze im SW eindeutig bestimmt. Barkal, Sanam Abu Dom und Kawa entgegentritt, Die Art der Verbindung zwischen B. 1200 und dem wie auch auf die weniger gut bekannte zivile Archi- Tempel B. 800 ist deshalb unklar, aber Spuren an der tektur, wobei die Trennlinie zwischen ‚sakralen‘ und Oberfläche deuten auf eine Trennmauer mit einem ‚profanen‘ Bauten im Bereich der königlichen Archi- Türdurchgang. tektur nicht immer scharf zu ziehen ist. Wichtig für die Interpretation von B. 1200 ist die Die Übernahmen erklären sich einerseits daraus, Lage des Gebäudes auf der rechten bzw. ‚Steuer- dass die Pharaonen der 25. -

Gebel Barkal (Sudan) No 1073

deceased, buried in a hypogeum underneath. In front of the Gebel Barkal (Sudan) pyramid a small temple was built, for offerings. In the cemetery of Gebel Barkal there are 30 explored tombs, most of them by G. A. Reisner and 5 recently by a No 1073 Spanish archaeological mission. The tombs are accessible by stairs and most of them are decorated, whether with paintings or angravings. 1. BASIC DATA Gebel Barkal site has still vast unexcavated nor studied, archaeological areas. State Party : Republic of Sudan El- Kurru; This Napatan cemetery is situated at a distance Name of property: Gebel Barkal and the Sites of the of 20 km from Gebel Barkal. It includes several royal Napatan Region tombs and royal family members burials. The cemetery was Location: Northern state, province of Meroe in use between the end of the 9th and the 7th centuries BC. The are different types of tombs in the cemetery, from the Date received: 28 June 2001 most simple, covered with a small tumulus, to the most Category of property: elaborate with a pyramid on top. In terms of the categories of cultural property set out in 34 tombs were excavated by Reisner between 1916 and Article 1 of the 1972 World Heritage Convention, these are 1918. sites. It is a serial nomination. Nuri: This cemetery contains 82 tombs, all excavated by Brief description: Reisner. Most of the tombs have pyramidal superstructures. The first burial in Nuri is from the year Several archaeological sites covering an area of more than 664 BC and the last from around 310 BC. -

Charles Bonnet Translated by Annie Grant

Charles Bonnet KERMA · PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE 2001-2002 AND 2002-2003 translated by Annie Grant SEASONS Once again we are able to report on major discoveries made at the site of Kerma. The town is situated in a region that has been densely occupied since ancient times, and is rich in remains that illustrate the evolution of Nubian cultures and its external relations and contri- butions. The expansion of cultivation and urbanisation threaten this extraordinary heritage that we have for many years worked to protect. Our research on the origins of Sudanese history has attracted a great deal of interest, and protecting and bringing to light these monuments remain priorities. Several publications have completed the work in the field1, and have been the source of fruitful exchanges with our international colleagues. The discovery on 11 January 2003 of a deposit of monumental statues was an exceptional event for Sudanese archæology and a fortiori for our Mission. These sculptures of the great Sudanese kings of the 25th Dynasty are of very fine quality, and shed new light on a period at Doukki Gel about which we previously knew very little. As a result of these finds, the site has gained in importance; it is of further benefit that they can be compared with the cache excavated 80 years ago by G. A. Reisner at the foot of Gebel Barkal, 200 kilo- metres away2. It will doubtless take several years to study and restore these statues; they were deliberately broken, most probably during Psametik II’s destructive raid into Nubia. We must thank the Swiss National Fund for Scientific Research, which regularly awards us a grant, and also the museums of art and history of the town of Geneva. -

Pre-Publication Proof

Contents List of Figures and Tables vii Preface xi List of Contributors xiii proof Introduction: Long-Distance Communication and the Cohesion of Early Empires 1 K a r e n R a d n e r 1 Egyptian State Correspondence of the New Kingdom: T e Letters of the Levantine Client Kings in the Amarna Correspondence and Contemporary Evidence 10 Jana Myná r ̌ová Pre-publication 2 State Correspondence in the Hittite World 3 2 Mark Weeden 3 An Imperial Communication Network: T e State Correspondence of the Neo-Assyrian Empire 64 K a r e n R a d n e r 4 T e Lost State Correspondence of the Babylonian Empire as Ref ected in Contemporary Administrative Letters 94 Michael Jursa 5 State Communications in the Persian Empire 112 Amé lie Kuhrt Book 1.indb v 11/9/2013 5:40:54 PM vi Contents 6 T e King’s Words: Hellenistic Royal Letters in Inscriptions 141 Alice Bencivenni 7 State Correspondence in the Roman Empire: Imperial Communication from Augustus to Justinian 172 Simon Corcoran Notes 211 Bibliography 257 Index 299 proof Pre-publication Book 1.indb vi 11/9/2013 5:40:54 PM Chapter 2 State Correspondence in the Hittite World M a r k W e e d e n T HIS chapter describes and discusses the evidence 1 for the internal correspondence of the Hittite state during its so-called imperial period (c. 1450– 1200 BC). Af er a brief sketch of the geographical and historical background, we will survey the available corpus and the generally well-documented archaeologi- cal contexts—a rarity among the corpora discussed in this volume. -

King Aspelta's Vessel Hoard from Nuri in the Sudan

JOURNAL of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston VOL.6, 1994 Fig. I. Pyramids at Nuri, Sudan, before excava- tion; Aspelta’s is the steeply sloped one, just left of the largest pyramid. SUSANNEGANSICKE King Aspelta’s Vessel Hoard from Nuri in the Sudan Introduction A GROUP of exquisite vessels, carved from translucent white stone, is included in the Museum of Fine Arts’s first permanent gallery of ancient Nubian art, which opened in May 1992. All originate from the same archaeological find, the tomb of King Aspelta, who ruled about 600-580 B.C. over the kingdom of Kush (also called Nubia), located along the banks of the Nile in what is today the northern Sudan. The vessels are believed to have contained perfumes or ointments. Five bear the king’s name, and three have his name and additional inscrip- tions. Several are so finely carved as to have almost eggshell-thin sides. One is decorated with a most unusual metal mount, fabricated from gilded silver, which has a curtain of swinging, braided, gold chains hanging from its rim, each suspending a jewel of colored stone. While all of Aspelta’s vessels display ingenious craftsmanship and pose important questions regarding the sources of their materials and places of manufacture, this last one is the most puzzling. The rim with hanging chains, for example, is a type of decoration previ- ously known only outside the Nile Valley on select Greek or Greek- influenced objects. A technical examination, carried out as part of the conservation work necessary to prepare the vessels for display, supplied many new insights into the techniques of their manufacture and clues to their possible origin. -

Through the Eras AHTTE.Ancntegypt.Tpgs 9/14/04 12:10 PM Page 3

AHTTE.AncntEgypt.tpgs 9/14/04 12:10 PM Page 1 ARTS & HUMANITIES Through the Eras AHTTE.AncntEgypt.tpgs 9/14/04 12:10 PM Page 3 ARTS & HUMANITIES \ Through the Eras Ancient Egypt 2675–332 B.C.E Edward Bleiberg, Editor 69742_AHTE_AEfm_iv-xxviii.qxd 9/21/04 1:20 PM Page iv Arts and Humanities Through The Eras: Ancient Egypt (2675 B.C.E.–332 B.C.E.) Edward Bleiberg Project Editor Indexing Services Product Design Rebecca Parks Barbara Koch Michelle DiMercurio Editorial Imaging and Multimedia Composition and Electronic Prepress Danielle Behr, Pamela A. Dear, Jason Everett, Randy Bassett, Mary K. Grimes, Lezlie Light, Evi Seoud Rachel J. Kain, Timothy Sisler, Ralph G. Daniel William Newell, Christine O’Bryan, Zerbonia Kelly A. Quin Manufacturing Wendy Blurton Editorial Support Services Rights and Acquisitions Mark Springer Margaret Chamberlain, Shalice Shah-Caldwell © 2005 Thomson Gale, a part of the This publication is a creative work fully Cover photographs by permission of Corbis Thomson Corporation. protected by all applicable copyright laws, as (seated statue of Pharaoh Djoser) and well as by misappropriation, trade secret, AP/Wide World Photos (“The Creation of Thomson and Star Logo are trademarks and unfair competition, and other applicable laws. Adam and Eve” detail by Orvieto). Gale is a registered trademark used herein The authors and editors of this work have under license. added value to the underlying factual Since this page cannot legibly accommo- material herein through one or more of the date all copyright notices, the acknowledge- For more information, contact following: unique and original selection, ments constitute an extension of the Thomson Gale coordination, expression, arrangement, and copyright notice. -

The Matrilineal Royal Succession in the Empire of Kush: a New Proposal Identifying the Kinship Terminology in the 25Th and Napatan Dynasties As That of Iroquois/Crow

2015 Varia Kumiko Saito The matrilineal royal Succession in the Empire of Kush: A new proposal Identifying the Kinship Terminology in the 25th and napatan Dynasties as that of Iroquois/Crow Introduction1 Various theories about the patterns of royal succes- sion in the 25th and Napatan Dynasties have been proposed. Macadam proposed a fratrilineal successi- on in which kingship passed from brother to brother and then to the children of the eldest brother.2 Török integrated the patrilineal, matrilineal, and fratrilineal succession systems.3 Kahn and Gozzoli4 take the position that the succession pattern in the 25th and in which some royal women held both the titles of Napatan Dynasties was basically patrilineal. It is snt nswt “king’s sister” and sAt nswt “king’s daughter”, noteworthy that, in Macadam’s and Török’s theories and this ground is regarded as decisive. However, this as well as the patrilineal succession, it is supposed that ignores the fact that it has been suggested that sn(t) all kings were sons of kings. I doubted this father- in its extended meaning may mean “cousin,” “aunt,” son relationship when I started inquiring into the “uncle,” “nephew,” or “niece.”5 If so, a daughter of matrilineal tradition in Kush. the previous king who had the title snt nswt could One of the textual grounds for accepting the be a cousin of the reigning king. It is also possible father-son relationship of the kings is the indirect one that the Kushite kingdom was a matrilineal society using a kinship terminology that was different from 1 This article is a revised version of my paper originally that of Egypt.