Art of Ancient Nubia Teaching Resources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nubian Contacts from the Middle Kingdom Onwards

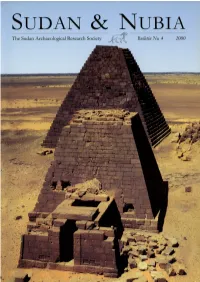

SUDAN & NUBIA 1 2 SUDAN & NUBIA 1 SUDAN & NUBIA and detailed understanding of Meroitic architecture and its The Royal Pyramids of Meroe. building trade. Architecture, Construction The Southern Differences and Reconstruction of a We normally connect the term ‘pyramid’ with the enormous structures at Gizeh and Dahshur. These pyramids, built to Sacred Landscape ensure the afterlife of the Pharaohs of Egypt’s earlier dynas- ties, seem to have nearly destroyed the economy of Egypt’s Friedrich W. Hinkel Old Kingdom. They belong to the ‘Seven Wonders of the World’ and we are intrigued by questions not only about Foreword1 their size and form, but also about their construction and the types of organisation necessary to build them. We ask Since earliest times, mankind has demanded that certain about their meaning and wonder about the need for such an structures not only be useful and stable, but that these same enormous undertaking, and we admire the courage and the structures also express specific ideological and aesthetic con- technical ability of those in charge. These last points - for cepts. Accordingly, one fundamental aspect of architecture me as a civil engineer and architect - are some of the most is the unity of ‘planning and building’ or of ‘design and con- important ones. struction’. This type of building represents, in a realistic and In the millennia following the great pyramids, their in- symbolic way, the result of both creative planning and tar- tention, form and symbolism have served as the inspiration get-orientated human activity. It therefore becomes a docu- for numerous imitations. However, it is clear that their origi- ment which outlasts its time, or - as was said a hundred years nal monumentality was never again repeated although pyra- ago by the American architect, Morgan - until its final de- mids were built until the Roman Period in Egypt. -

Graffiti-As-Devotion.Pdf

lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ i lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iii Edited by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis Along the Nile and Beyond Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Kelsey Museum of Archaeology University of Michigan, 2019 lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/ iv Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile and Beyond The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, Ann Arbor 48109 © 2019 by The Kelsey Museum of Archaeology and the individual authors All rights reserved Published 2019 ISBN-13: 978-0-9906623-9-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019944110 Kelsey Museum Publication 16 Series Editor Leslie Schramer Cover design by Eric Campbell This book was published in conjunction with the special exhibition Graffiti as Devotion along the Nile: El-Kurru, Sudan, held at the Kelsey Museum of Archaeology in Ann Arbor, Michigan. The exhibition, curated by Geoff Emberling and Suzanne Davis, was on view from 23 August 2019 through 29 March 2020. An online version of the exhibition can be viewed at http://exhibitions.kelsey.lsa.umich.edu/graffiti-el-kurru Funding for this publication was provided by the University of Michigan College of Literature, Science, and the Arts and the University of Michigan Office of Research. This book is available direct from ISD Book Distributors: 70 Enterprise Drive, Suite 2 Bristol, CT 06010, USA Telephone: (860) 584-6546 Email: [email protected] Web: www.isdistribution.com A PDF is available for free download at https://lsa.umich.edu/kelsey/publications.html Printed in South Korea by Four Colour Print Group, Louisville, Kentucky. ♾ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

Die Profanarchitektur Der Napatanischen Epoche

2015 Varia Uwe Sievertsen Die Profanarchitektur der napatanischen Epoche Einleitung erscheint, auch der Übergang zur meroitischen Zeit in die Betrachtung einbezogen. In der Zeit vor und um die Mitte des 1. Jts. v. Chr. waren Königtum und gesellschaftliche Eliten im Reich von Kusch nicht nur durch eigenständige Herrscherpaläste kulturelle Traditionen, sondern auch durch viel- fältige Einflüsse aus dem nördlichen Nachbarland Einen Eindruck vom Aussehen kuschitischer Herr- Ägypten geprägt. scherpaläste aus napatanischer Zeit vermittelt bis- Die Anklänge und Entlehnungen lassen sich etwa lang einzig der Palast B. 1200 von Gebel Barkal. in der Schrift, in den Grabsitten sowie in der Rund- Der sogenannte Napatan Palace liegt südwestlich und Reliefplastik, aber ebenso in der architektoni- der beiden parallel ausgerichteten Amuntempel B. schen Hinterlassenschaft beobachten. Dort erstrek- 500 und B. 800 (Abb. 1-2).2 Er beschreibt ein gro- ken sie sich auf die Sakralarchitektur, wie sie uns ßes Rechteck von rund 70 x 45 m Fläche, doch ist beispielhaft in den großen Amuntempeln von Gebel nur die Gebäudegrenze im SW eindeutig bestimmt. Barkal, Sanam Abu Dom und Kawa entgegentritt, Die Art der Verbindung zwischen B. 1200 und dem wie auch auf die weniger gut bekannte zivile Archi- Tempel B. 800 ist deshalb unklar, aber Spuren an der tektur, wobei die Trennlinie zwischen ‚sakralen‘ und Oberfläche deuten auf eine Trennmauer mit einem ‚profanen‘ Bauten im Bereich der königlichen Archi- Türdurchgang. tektur nicht immer scharf zu ziehen ist. Wichtig für die Interpretation von B. 1200 ist die Die Übernahmen erklären sich einerseits daraus, Lage des Gebäudes auf der rechten bzw. ‚Steuer- dass die Pharaonen der 25. -

Gebel Barkal (Sudan) No 1073

deceased, buried in a hypogeum underneath. In front of the Gebel Barkal (Sudan) pyramid a small temple was built, for offerings. In the cemetery of Gebel Barkal there are 30 explored tombs, most of them by G. A. Reisner and 5 recently by a No 1073 Spanish archaeological mission. The tombs are accessible by stairs and most of them are decorated, whether with paintings or angravings. 1. BASIC DATA Gebel Barkal site has still vast unexcavated nor studied, archaeological areas. State Party : Republic of Sudan El- Kurru; This Napatan cemetery is situated at a distance Name of property: Gebel Barkal and the Sites of the of 20 km from Gebel Barkal. It includes several royal Napatan Region tombs and royal family members burials. The cemetery was Location: Northern state, province of Meroe in use between the end of the 9th and the 7th centuries BC. The are different types of tombs in the cemetery, from the Date received: 28 June 2001 most simple, covered with a small tumulus, to the most Category of property: elaborate with a pyramid on top. In terms of the categories of cultural property set out in 34 tombs were excavated by Reisner between 1916 and Article 1 of the 1972 World Heritage Convention, these are 1918. sites. It is a serial nomination. Nuri: This cemetery contains 82 tombs, all excavated by Brief description: Reisner. Most of the tombs have pyramidal superstructures. The first burial in Nuri is from the year Several archaeological sites covering an area of more than 664 BC and the last from around 310 BC. -

King Aspelta's Vessel Hoard from Nuri in the Sudan

JOURNAL of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston VOL.6, 1994 Fig. I. Pyramids at Nuri, Sudan, before excava- tion; Aspelta’s is the steeply sloped one, just left of the largest pyramid. SUSANNEGANSICKE King Aspelta’s Vessel Hoard from Nuri in the Sudan Introduction A GROUP of exquisite vessels, carved from translucent white stone, is included in the Museum of Fine Arts’s first permanent gallery of ancient Nubian art, which opened in May 1992. All originate from the same archaeological find, the tomb of King Aspelta, who ruled about 600-580 B.C. over the kingdom of Kush (also called Nubia), located along the banks of the Nile in what is today the northern Sudan. The vessels are believed to have contained perfumes or ointments. Five bear the king’s name, and three have his name and additional inscrip- tions. Several are so finely carved as to have almost eggshell-thin sides. One is decorated with a most unusual metal mount, fabricated from gilded silver, which has a curtain of swinging, braided, gold chains hanging from its rim, each suspending a jewel of colored stone. While all of Aspelta’s vessels display ingenious craftsmanship and pose important questions regarding the sources of their materials and places of manufacture, this last one is the most puzzling. The rim with hanging chains, for example, is a type of decoration previ- ously known only outside the Nile Valley on select Greek or Greek- influenced objects. A technical examination, carried out as part of the conservation work necessary to prepare the vessels for display, supplied many new insights into the techniques of their manufacture and clues to their possible origin. -

The Matrilineal Royal Succession in the Empire of Kush: a New Proposal Identifying the Kinship Terminology in the 25Th and Napatan Dynasties As That of Iroquois/Crow

2015 Varia Kumiko Saito The matrilineal royal Succession in the Empire of Kush: A new proposal Identifying the Kinship Terminology in the 25th and napatan Dynasties as that of Iroquois/Crow Introduction1 Various theories about the patterns of royal succes- sion in the 25th and Napatan Dynasties have been proposed. Macadam proposed a fratrilineal successi- on in which kingship passed from brother to brother and then to the children of the eldest brother.2 Török integrated the patrilineal, matrilineal, and fratrilineal succession systems.3 Kahn and Gozzoli4 take the position that the succession pattern in the 25th and in which some royal women held both the titles of Napatan Dynasties was basically patrilineal. It is snt nswt “king’s sister” and sAt nswt “king’s daughter”, noteworthy that, in Macadam’s and Török’s theories and this ground is regarded as decisive. However, this as well as the patrilineal succession, it is supposed that ignores the fact that it has been suggested that sn(t) all kings were sons of kings. I doubted this father- in its extended meaning may mean “cousin,” “aunt,” son relationship when I started inquiring into the “uncle,” “nephew,” or “niece.”5 If so, a daughter of matrilineal tradition in Kush. the previous king who had the title snt nswt could One of the textual grounds for accepting the be a cousin of the reigning king. It is also possible father-son relationship of the kings is the indirect one that the Kushite kingdom was a matrilineal society using a kinship terminology that was different from 1 This article is a revised version of my paper originally that of Egypt. -

Nubia: Treasures of Ancient Africa

Audio Guide Transcript Nubia: Treasures of Ancient Africa April 18–August 22, 2021 Main Exhibition Galleries STOP 1 Introduction Gallery: Director’s Welcome Speaker: Brent Benjamin Barbara B. Taylor Director Saint Louis Art Museum Hello, I’m Brent Benjamin, Barbara B. Taylor Director of the Saint Louis Art Museum. It is my pleasure to welcome you to the audio guide for Nubia: Treasures of Ancient Africa. The exhibition presents the history and artistic achievements of ancient Nubia and showcases the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, through magnificent jewelry, pottery, sculpture, metalwork, and more. For nearly 3,000 years a series of Nubian kingdoms flourished in the Nile River valley in what is today Sudan. The ancient Nubians controlled vast empires and trade networks and left behind the remains of cities, temples, palaces, and pyramids but few written records. As a result, until recently their story has been told in large part by others—in antiquity by their more famous Egyptian neighbors and rivals, and in the early 20th century by American and European scholars and archaeologists. Through art, this exhibition addresses past misunderstandings and misinterpretations and offers new ways of understanding Nubia’s dynamic history and relevance, which raises issues of power, representation, and cultural bias that were as relevant in past centuries as they are today. This exhibition audio guide offers expert commentaries from Denise Doxey, guest curator of this exhibition and curator of ancient Egyptian, Nubian, and Near Eastern art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The guide features a selection of objects from various ancient Nubian kingdoms and shares insights into the daily life of the Nubians, their aesthetic preferences, religious beliefs, technological inventiveness, and relations with other ancient civilizations. -

Ninth International Conference of the Society for Nubian Studies, 21

Originalveröffentlichung in: Mitteilungen der Sudanarchäologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin e.V. 9, 1999, S. 58-62 58 TAGUNGEN ANGELIKA LOHWASSER NINTH INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE OF THE SOCIETY FOR NUBIAN STUDIES, 21. - 26. AUGUST 1998 IN BOSTON Die 1972 gegründete International Society for Organisatoren der Tagung ist es zu verdanken, Nubian Studies widmet sich vorrangig der För daß das Relief des Arikankharor, das normaler derung der Erforschung des antiken Sudan (siehe weise im Worcester Museum of Art ausgestellt die Informationen über die Society in MittSAG ist, für die Dauer des Kongresses in Boston zu 1, 1994: 2021). Alle vier Jahre versammeln sich besichtigen war (Africa in Antiquity I: 15). Für die Nubiologen, um einen Kongreß abzuhalten jeden Nubiologen ist der Besuch der schön prä und dabei die neuesten wissenschaftlichen sentierten "Nubian Gallery" ein Leckerbissen Ergebnisse auszutauschen. 1994 fand die 8. eine Möglichkeit, die die Kongreßbesucher Internationale Nubiologenkonferenz in Lille gerne nutzten. Ebenso wurde von der Möglich (Frankreich) statt; dort wurde beschlossen, die keit Gebrauch gemacht, den 12 Tonnen schwe 9. Konferenz im Museum of Fine Arts, Boston ren Sarkophag des Aspelta (MFA 23.729), der (USA) abzuhalten. wegen seines Gewichts nur im Magazin im Kel Zu Boston haben all diejenigen, die sich inten ler stehen kann, zu besichtigen. Dieser Sarko siver mit Nubien und dem antiken Sudan phag und der nahezu identische des Anlamani beschäftigen, eine besondere Beziehung: Der (National Museum Khartoum 1868) sind die ein Ausgräber George Andrew Reisner den mei zigen Steinsärge, die wir von den kuschitischen sten Ägyptologen durch seine Grabungen in Königen haben. Die darauf geschriebenen Texte Giza bekannt war der Leiter der großen archäo sind ähnlich denen der Könige der 18. -

Journal of Egyptian Archaeology

Journal of Egyptian Archaeology Past and present members of the staff of the Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Stelae, Reliefs and Paintings, especially R. L. B. Moss and E. W. Burney, have taken part in the analysis of this periodical and the preparation of this list at the Griffith Institute, University of Oxford This pdf version (situation on 14 July 2010): Jaromir Malek (Editor), Diana Magee, Elizabeth Fleming and Alison Hobby (Assistants to the Editor) Naville in JEA I (1914), pl. I cf. 5-8 Abydos. Osireion. vi.29 View. Naville in JEA I (1914), pl. ii [1] Abydos. Osireion. Sloping Passage. vi.30(17)-(18) Osiris and benu-bird from frieze. see Peet in JEA i (1914), 37-39 Abydos. Necropolis. v.61 Account of Cemetery D. see Peet in JEA i (1914), 39 Abydos. Necropolis. Ibis Cemetery. v.77 Description. see Loat in JEA i (1914), 40 and pl. iv Abydos. Necropolis. Ibis Cemetery. v.77 Description and view. Blackman in JEA i (1914), pl. v [1] opp. 42 Meir. Tomb of Pepiankh-h. ir-ib. iv.254 View. Blackman in JEA i (1914), pl. v [2] opp. 42 Meir. Tomb of Pepiankh-h. ir-ib. iv.255(16) Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Stelae, Reliefs and Paintings Griffith Institute, Sackler Library, 1 St John Street, Oxford OX1 2LG, United Kingdom [email protected] 2 Group with calf from 2nd register. Petrie in JEA i (1914), pl. vi cf. 44 El-Riqqa. Finds. iv.87 Part of jewellery, temp. -

"Napatan" Dynasty (From 656 to the Mid-3Rd Cent

CHAPTER SIX THE KINGDOM OF KUSH BETWEEN THE WITHDRAWAL FROM EGYPT AND THE END OF THE "NAPATAN" DYNASTY (FROM 656 TO THE MID-3RD CENT. BC) "Then this god said to His Majesty, 'You shall give me the lands that were taken from me. ,,1 1. THE SOURCES 1.1. Textual evidence From the twenty-nine royal documents in hieroglyphic Egyptian listed in Table A (Ch. II.l.l.l ), seventeen date from the period discussed in this chapter. The monumental inscriptions of Anlamani, Aspelta, Irike Amannote, Harsiyotef and Nastasefi present valuable information on concepts of the myth of the state and the developments in the legiti mation process. They were analysed from these particular aspects as well as from the viewpoint of the structure of Kushite government in earlier chapters in this book (Ch. V.3-5). As documents of political and cultural history, they will be discussed in this chapter, together with the rest of the royal inscriptions preserved from this period, which are, however, fragmentary or pertain to special issues as building or restora tion and economic management of temples. Besides monumental royal documents, there are hieroglyphic texts connected to temple cults and mortuary religion from this period. These will be touched upon in Ch. VI.3.2. The historical evidence is complemented with hieroglyphic Egyptian and Greek documents relating to the Nubian campaign of Psamtik II in 593 BC (Ch. VI.2.1-2), further with Herodotus' remarks on Nubian history and culture (c£ Ch. II.l.2.2) and a number of remarks of varying historical value in works of Greek and Latin 1 Irike-Amannote inscription, Kawa IX, line 60, FHNII No. -

From the Fjords to the Nile. Essays in Honour of Richard Holton Pierce

From the Fjords to the Nile brings together essays by students and colleagues of Richard Holton Pierce (b. 1935), presented on the occasion of his 80th birthday. It covers topics Steiner, Tsakos and Seland (eds) on the ancient world and the Near East. Pierce is Professor Emeritus of Egyptology at the University of Bergen. Starting out as an expert in Egyptian languages, and of law in Greco-Roman Egypt, his professional interest has spanned from ancient Nubia and Coptic Egypt, to digital humanities and game theory. His contribution as scholar, teacher, supervisor and informal advisor to Norwegian studies in Egyptology, classics, archaeology, history, religion, and linguistics through more than five decades can hardly be overstated. Pål Steiner has an MA in Egyptian archaeology from K.U. Leuven and an MA in religious studies from the University of Bergen, where he has been teaching Ancient Near Eastern religions. He has published a collection of Egyptian myths in Norwegian. He is now an academic librarian at the University of Bergen, while finishing his PhD on Egyptian funerary rituals. Alexandros Tsakos studied history and archaeology at the University of Ioannina, Greece. His Master thesis was written on ancient polytheisms and submitted to the Université Libre, Belgium. He defended his PhD thesis at Humboldt University, Berlin on the topic ‘The Greek Manuscripts on Parchment Discovered at Site SR022.A in the Fourth Cataract Region, North Sudan’. He is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Bergen with the project ‘Religious Literacy in Christian Nubia’. He From the Fjords to Nile is a founding member of the Union for Nubian Studies and member of the editorial board of Dotawo. -

Palace and Temple Edited by Rolf Gundlach and Kate Spence

KÖNIGTUM, STAAT UND GESELLSCHAFT FRÜHER HOCHKULTUREN 4,2 5. Symposium zur ägyptischen Königsideologie/ 5th Symposium on Egyptian Royal Ideology Palace and Temple Edited by Rolf Gundlach and Kate Spence Harras sowitz Verlag KÖNIGTUM, STAAT UND GESELLSCHAFT FRÜHER HOCHKULTUREN Herausgegeben von Rolf Gundlach, Detlev Kreikenbom und Mechthild Schade-Busch 4,2 Beiträge zur altägyptischen Königsideologie Herausgegeben von Horst Beinlich, Rolf Gundlach und Ursula Rößler-Köhler 2011 Harrassowitz Verlag • Wiesbaden 5. Symposium zur ägyptischen Königsideologie/ 5th Symposium on Egyptian Royal Ideology Palace and Temple Architecture - Decoration - Ritual Cambridge, July, 16th-17th, 2007 Edited by Rolf Gundlach and Kate Spence 2011 Harrassowitz Verlag • Wiesbaden The proceedings of the first three Symposien zur ägyptischen Königsideologie are published in volume 36, part 1, 2 and 3 of the series „Ägypten und Altes Testament". Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsehe Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie: detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Bibliographie information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothck lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie: detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. For further information about our publishing program consult our website http://www.harrassowitz-verlag.de © Otto Harrassowitz GmbH & Co. KG,