Recent Western Historiography of the Time of Troubles in Russia M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Borys Godunow Modest Musorgski

~~ OFICJALNY PARTNER SEZONU OPERY WROCŁAWSKIEJ ~ TAURON AN OrnCIAl PAlRO Of WROCIA I OPLR ~E ON POLSKA ENERGIA OPERA WROCŁAWSKA ~ INSTYTUCJA KULTURY SAMORZĄDU WOJEWÓDZTWA DOLNO~l.ĄSKIEGO WSPÓŁPROWADZONA PRZEZ MINISTRA KULTURY I DZIEDZICTWA NARODOWEGO EWA MICHNIK DYREKTOR NACZELNY I ARTYSTYCZNY BORYS GODUNOW MODEST MUSORGSKI INSTRUMENTACJA I ORCHESTRATION MIKOW RIMSKI-KORSAKOW OPERA W 4 AKTACH Z PROLOGIEM I OPERA I 4 ACTS ITH PRO LO GUE LIBRETIO - MODEST MUSORGSKI WG KRONIKI DRAMATYCZNEJ ALEKSANDRA PUSZKINA MODEST MUSSDRGSKY ACCORDING TO ALEXANDER PUSHKI N'S DRAMATIC CHRON ICLE PETERSBURG,'l874 - PRAPREMIERA I PR EVIEW LWÓW, 1912 - PREMIERA POLSKA I POUSH PREM IER E PREMIERA i PREM IER E SO I SA 24.04.2010· 19.00 NO I su 25.04.2010" 17.00 czw I TH 29.04.2010" 19.00 PT I FR 30.04.2010 19.00 'SPEKTAKL Z G W I AZDĄ I PERFORMANCE Wll H GUEST STAR CZAS TRWANIA SPEKTAKLU I DURATION : 180 MIN. 2 PRZERWY I 2 ll•TERVALS SPEKTAKL WYKONYWANY JEST W JĘZYKU ROSYJSKIM Z POLSKIMI NAPISAMI RUSSIAN lANGUAG EVERS IO N WITH POUSH SUBTITLES BOR YS GO DUNOW I ODE ST MUSORGS I REALIZATORLY I P RODUCfR~ REALIZATORZY I PRODUCERS EWA MICHNIK KIEROWN ICTWO MUZYCZNE, DYRYGENT I MU SIC DIR ECTION, CONDU CTO R WALDEMAR ZAWODZIŃSKI REŻYSER I A I SCE NOGRAFIA I STAG E DIR ECTION Et SET DESIGNS MAŁGORZATA SŁONIOWSKA KO STI UMY I COSTUM E DESIGN S JANINA NI ESOBSKA CHOREOGRAFIA I RUCH SC ENICZNY I CHOREOGRAP HY AND STAGE MOVEMENT ANNA GRABOWSKA-BORYS PRZYGOTOWANIE CHÓRU I CHORUS MASTER ANDRZEJ PĄGOWSKI PLAKAT I POSTER BASSEM AKIKI ASYSTE NT„ DYRYGENTA I AS SISTANT CONDUCTOR HANNA MARASZ ASY STENT REŻ YS ERA I ASSISTANT STAGE DIRE CTOR KATARZYNA ZBŁOWSKA ASY STENT SCENOGRAFA I ASSISTANT SE T DES IGNER MONIKA TROPPER ASYSTENT KI ER OWN IKA CHÓR U I ASS ISTAN T CHORU S MASTER PRZEMYSŁAW KLONOWSKI ASYSTENT REŻYS ER A - S TAŻY STA I ASS ISTANT STAGE DIRECTOR - TRAINEE BARBARA JAKÓBCZAK-ZATHEY, MARIA RZEMIENIECKA , JUSTYNA SKOCZEK . -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-81227-6 - The Cambridge History of Russia, Volume 1: From Early Rus’ to 1689 Edited by Maureen Perrie Index More information Index Aadil Girey, khan of Crimea 507 three-field 293, 294 Abatis defensive line (southern frontier) 491, tools and implements 291–2 494, 497 in towns 309, 598 Abbasids, Caliphate of 51 Ahmed, khan of the Great Horde 223, 237, Abibos, St 342 321 absolutism, as model of Russian and Akakii, Bishop of Tver’ 353 Muscovite states 16 Alachev, Mansi chief 334 Acre, merchants in Kiev 122 Aland˚ islands, possible origins of Rus’ in 52, Adalbert, bishop, mission to Rus’ 58, 60 54 Adashev, Aleksei Fedorovich, courtier to Albazin, Fort, Amur river 528 Ivan IV 255 alcohol Adrian, Patriarch (d. 1700) 639 peasants’ 289 Adyg tribes 530 regulations on sale of 575, 631 Afanasii, bishop of Kholmogory, Uvet Aleksandr, bishop of Viatka 633, 636 dukhovnyi 633 Aleksandr, boyar, brother of Metropolitan Agapetus, Byzantine deacon 357, 364 Aleksei 179 ‘Agapetus doctrine’ 297, 357, 364, 389 Aleksandr Mikhailovich (d.1339) 146, 153, 154 effect on law 378, 379, 384 as prince in Pskov 140, 152, 365 agricultural products 39, 315 as prince of Vladimir 139, 140 agriculture 10, 39, 219, 309 Aleksandr Nevskii, son of Iaroslav arable 25, 39, 287 (d.1263) 121, 123, 141 crop failures 42, 540 and battle of river Neva (1240) 198 crop yields 286, 287, 294, 545 campaigns against Lithuania 145 effect on environment 29–30 and Metropolitan Kirill 149 effect of environment on 10, 38 as prince of Novgorod under Mongols 134, fences 383n. -

Compilation A...L Version.Pdf

Compilation and Translation Johannes Widekindi and the Origins of his Work on a Swedish-Russian War Vetushko-Kalevich, Arsenii 2019 Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Vetushko-Kalevich, A. (2019). Compilation and Translation: Johannes Widekindi and the Origins of his Work on a Swedish-Russian War. Lund University. Total number of authors: 1 Creative Commons License: Unspecified General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Compilation and Translation Johannes Widekindi and the Origins of his Work on a Swedish-Russian War ARSENII VETUSHKO-KALEVICH FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND THEOLOGY | LUND UNIVERSITY The work of Johannes Widekindi that appeared in 1671 in Swedish as Thet Swenska i Ryssland Tijo åhrs Krijgz-Historie and in 1672 in Latin as Historia Belli Sveco-Moscovitici Decennalis is an important source on Swedish military campaigns in Russia at the beginning of the 17th century. -

Zemskii Sobor: Historiographies and Mythologies of a Russian “Parliament”1

Zemskii Sobor: Historiographies and Mythologies of a Russian “Parliament”1 Ivan Sablin University of Heidelberg Kuzma Kukushkin Peter the Great Saint Petersburg Polytechnic University Abstract Focusing on the term zemskii sobor, this study explored the historiographies of the early modern Russian assemblies, which the term denoted, as well as the autocratic and democratic mythologies connected to it. Historians have discussed whether the individual assemblies in the sixteenth and seventeenth century could be seen as a consistent institution, what constituencies were represented there, what role they played in the relations of the Tsar with his subjects, and if they were similar to the early modern assemblies elsewhere. The growing historiographic consensus does not see the early modern Russian assemblies as an institution. In the nineteenth–early twentieth century, history writing and myth-making integrated the zemskii sobor into the argumentations of both the opponents and the proponents of parliamentarism in Russia. The autocratic mythology, perpetuated by the Slavophiles in the second half of the nineteenth century, proved more coherent yet did not achieve the recognition from the Tsars. The democratic mythology was more heterogeneous and, despite occasionally fading to the background of the debates, lasted for some hundred years between the 1820s and the 1920s. Initially, the autocratic approach to the zemskii sobor was idealistic, but it became more practical at the summit of its popularity during the Revolution of 1905–1907, when the zemskii sobor was discussed by the government as a way to avoid bigger concessions. Regionalist approaches to Russia’s past and future became formative for the democratic mythology of the zemskii sobor, which persisted as part of the romantic nationalist imagery well into the Russian Civil War of 1918–1922. -

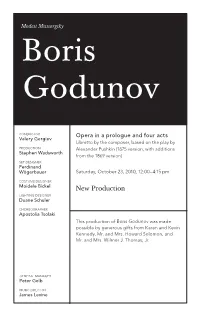

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

CHESTER S. L. DUNNING August 2012

CHESTER S. L. DUNNING August 2012 Department of History Texas A&M University College Station, Texas 77843-4236 (979) 845-7166 e-mail: [email protected] DEGREES RECEIVED: B.A. University of California at Santa Cruz 1971 Highest Honors in History, College Honors M.A. Boston College 1972 (with distinction) major field: Russian history minor fields: Early modern Europe, American history to 1900 Ph.D. Boston College 1976 (with distinction) major field: Russian history minor fields: Early modern Europe, Comparative early modern European history, American history to Reconstruction ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS: Lecturer Boston College 1975-76 Assistant Professor Pembroke State University 1977-79 University Honors Professor Pembroke State University 1978-79 Assistant Professor Texas A&M University 1979-85 Associate Professor Texas A&M University 1985-2002 Visiting Scholar Harvard University 1987-88 Professor Texas A&M University 2002- Eppright Professor Texas A&M University 2005-2008 Fasken Chair Texas A&M University 2012- Fulbright Visiting Professor University of Aberdeen, Scotland 2013 TEACHING FIELDS: UNDERGRADUATE Russian Civilization Medieval and Early Modern Russian History Early Modern Europe Rise of the European Middle Class Imperial Russia, 1801-1917 History of the Soviet Union Eastern Europe Since 1453 Western Civilization 2 TEACHING FIELDS: GRADUATE Early Modern Russia Early Modern Europe Medieval Russia Imperial Russia The Russian Revolution and Civil War Historiography SUPERVISION OF INDEPENDENT GRADUATE WORK: Chair M.A. Committee Ann Todd Baum Completed, 1985 Chair M.A. Committee Cassandra Bell Completed, 1991 Chair M.A. Committee James Vargas Completed, 1993 Chair M.A. Committee Lisa Tauferner Completed, 2007 Chair M.A. Committee Mark Douglass Completed, 2009 Chair M.A. -

The Muscovite Embassy of 1599 to Emperor Rudolf II of Habsburg

The Muscovite Embassy of 1599 to Emperor Rudolf II of Habsburg Isaiah Gruber Depanment of History M~GillUniversity, Montreal January 1999 A thesis subrnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Ans. Copyright 8 Isaiah Gruber, 1999. National Library Biblbthdy nationaie dCatWa du Cana a AqkMons and Acquisitions et Bibliognphic Services services bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive licence allowhg the exclusive permettant à la National Libfary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distnbute or seil reproduire, prêter, disûi'buer ou copies of this thesis in microfom, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fonnat électronique, The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial exûacts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract The present thesis represents a contribution to the history of diplornatic relations between Muscovy and the House of Habsburg. It includes an ovedl survey of those relations during the reign of Tsar Fyodor (1584-1598), as well as a more deiailed study of the Muscovite embassy of 1599. It also provides original translations of important Russian documents nlated to the subject of the thesis. -

Historic Centre of the City of Yaroslavl”

World Heritage Scanned Nomination File Name: 1170.pdf UNESCO Region: EUROPE AND NORTH AMERICA __________________________________________________________________________________________________ SITE NAME: Historical Centre of the City of Yaroslavl DATE OF INSCRIPTION: 15th July 2005 STATE PARTY: RUSSIAN FEDERATION CRITERIA: C (ii)(iv) DECISION OF THE WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE: Excerpt from the Decisions of the 29th Session of the World Heritage Committee Criterion (ii): The historic town of Yaroslavl with its 17th century churches and its Neo-classical radial urban plan and civic architecture is an outstanding example of the interchange of cultural and architectural influences between Western Europe and Russian Empire. Criterion (iv): Yaroslavl is an outstanding example of the town-planning reform ordered by Empress Catherine The Great in the whole of Russia, implemented between 1763 and 1830. BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS Situated at the confluence of the Volga and Kotorosl rivers some 250km northeast of Moscow, the historic city of Yaroslavl developed into a major commercial centre as of the 11th century. It is renowned for its numerous 17th-century churches and is an outstanding example of the urban planning reform Empress Catherine the Great ordered for the whole of Russia in 1763. While keeping some of its significant historic structures, the town was renovated in the neo-classical style on a radial urban master plan. It has also kept elements from the 16th century in the Spassky Monastery, one of the oldest in the Upper Volga region, built on -

The Time of Troubles in Alexander Dugin's Narrative

European Review, Vol. 27, No. 1, 143–157 © 2018 Academia Europæa doi:10.1017/S1062798718000650 The Time of Troubles in Alexander Dugin’s Narrative DMITRY SHLAPENTOKH DW 332, Indiana University South Bend, 1700 Mishawaka Avenue, South Bend, IN 46615, USA. Email: [email protected] Alexander Dugin (b. 1962) is one of the best-known philosophers and public intellectuals of post-Soviet Russia. While his geopolitical views are well-researched, his views on Russian history are less so. Still, they are important to understand his Weltanschauung and that of like-minded Russian intellectuals. For Dugin, the ‘Time of Troubles’–the period of Russian history at the beginning of the seven- teenth century marked by dynastic crisis and general chaos – constitutes an expla- natory framework for the present. Dugin implicitly regarded the ‘Time of Troubles’ in broader philosophical terms. For him, the ‘Time of Troubles’ meant not purely political and social upheaval/dislocation, but a deep spiritual crisis that endangered the very existence of the Russian people. Russia, in his view, has undergone several crises during its long history. Each time, however, Russia has risen again and achieved even greater levels of spiritual wholeness. Dugin believed that Russia was going through a new ‘Time of Troubles’. In the early days of the post-Soviet era, he believed that it was the collapse of the USSR that had led to a new ‘Time of Troubles’. Later, he changed his mind and proclaimed that the Soviet regime was not legitimate at all and, consequently, that the ‘Time of Troubles’ started a century ago in 1917. -

In Association with Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, Henry Joyce, and the Alexander Palace Association the ALEXANDER PALACE

THE ALEXANDER PALACE TSARSKOE SELO, ST. PETERSBURG, RUSSIA PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR RESTORATION AND ADAPTIVE RE-USE \ ~ - , •I I THE WORLD MONUMENTS FUND in Association with Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, Henry Joyce, and The Alexander Palace Association THE ALEXANDER PALACE TSARSKOE SELO, ST. PETERSBURG, RUSSIA PRELIMINARY ASSESSMENT REpORT FOR RESTORATION AND ADAPTIVE RE-USE Mission I: February 9-15, 1995 Mission II: June 26-29,1995 Mission III: July 22-26, 1996 THE WORLD MONUMENTS FUND in Association with Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, Henry Joyce, and The Alexander Palace Association June 1997 Enfilade, circa 1945 showing war damage (courtesy Tsarskoe Selo Museum) The research and compilation of this report have been made possible by generous grants from the following contributors Delta Air Lines The Samuel H. Kress Foundation The Charles and Betti Saunders Foundation The Trust for Mutual Understanding Cover: The Alexander Palace, February 1995. Photograph by Kirk Tuck & Michael Larvey. Acknowledgements The World Monuments Fund, Page Ayres Cowley Architects, LLP, and Henry Joyce wish to extend their gratitude to all who made possible the series of international missions that resulted in this document. The World Monuments Fund's initial planning mission to St. Petersburg in 1995 was organized by the office of Mayor Anatoly Sobchak and the members of the Alexander Palace Association. The planning team included representatives of the World Monuments Fund, Page Ayres Cowley Architects, and the Alexander Palace Association, accompanied by Henry Joyce. This preliminary report and study tour was made possible by grants from the Samuel H. Kress Foundation and the Trust for Mutual Understanding. -

Download Free Sampler

Thank you for downloading this free sampler of: WRITING THE TIME OF TROUBLES False Dmitry in Russian Literature MARCIA A. MORRIS Series: The Unknown Nineteenth Century August 2018 | 192 pp. 9781618118639 | $99.00 | Hardback SUMMARY . Is each moment in history unique, or do essential situations repeat themselves? The traumatic events associated with the man who reigned as Tsar Dmitry have haunted the Russian imagination for four hundred years. Was Dmitry legitimate, the last scion of the House of Rurik, or was he an upstart pretender? A harbinger of Russia’s doom or a herald of progress? Writing the Time of Troubles traces the proliferation of fictional representations of Dmitry in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Russia, showing how playwrights and novelists reshaped and appropriated his brief and equivocal career as a means of drawing attention to and negotiating the social anxieties of their own times. ABOUT THE AUTHOR . Marcia A. Morris is Professor of Slavic Languages at Georgetown University. She is the author of Saints and Revolutionaries: The Ascetic Hero in Russian Literature, The Literature of Roguery in Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Russia, and Russian Tales of Demonic Possession: Translations of Savva Grudtsyn and Solomonia. 20% off with the promotional code MORRIS at www.academicstudiespress.com Free sampler. Copyrighted material. WRITING THE TIME OF TROUBLES False Dmitry in Russian Literature Free sampler. Copyrighted material. The Unknown Nineteenth Century Series Editor JOE PESCHIO (University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee) Editorial Board ANGELA BRINTLINGER (Ohio State University, Columbus) ALYSSA GILLESPIE (University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana) MIKHAIL GRONAS (Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire) IGOR PILSHCHIKOV (Tallinn University, Moscow State University) DAVID POWELSTOCK (Brandeis University, Waltham, Massachusetts) ILYA VINITSKY (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia) Free sampler. -

Advertising 1

advertising 1. В английском тексте вместо * ставь 123. Текст 123 выделен желтым 2. В русском тексте 123 обрати внимание фраза 2 скорректирована. Ее так же необходимо изменить 3. Сами цифры 123 должны быть меньшего размера чем текст в обоих версиях 4. Фраза в англ версии спикинг на коннектинг вчерашний файл прикладываю 5. Пункт V-Tell phone numbers of…. Его надо сократить убрав последних два предложения про выбор номера и визитки 6. Проверь орфографию и дублирования всякие. Это крайня я версия ее в печать Жду V - T E L L . R U 1. Из перечня стран, указанного на сайте v-tell.ru 2. В пределах доступных в системе номеров 3. При наличии номера страны вызывающего абонента TO PARTICIPANTS, GUESTS AND ORGANIZERS OF THE ST. PETERSBURG INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC FORUM DEAR FRIENDS, It is a great pleasure to welcome you to the St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, which this year is taking place under the theme Achieving a New Balance in the Global Economic Arena. For the first time in the last several years, the global economy is showing signs of recovery. The Forum will discuss how to consolidate the emerging trends and assess the risks and challenges related to the introduction of new technologies. The sweeping changes taking place today require effective measures by the international community to enhance the international governance architecture in order to take coordinated steps to ensure that all population groups benefit from the fruits of globalization and thereby guarantee sustainable and balanced development. Over these years, the Forum has gained substantial authority as a recognized global discussion platform open for direct and engaged dialogue on the relevant issues we face today.