POLARIZED PROGRESS Social Acceptance of LGBT People in 141 Countries, 1981 to 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chartbook on Women's Progress

FUTURE OF WORK@50+ NOVEMBERMONTH 2015 Research Report Looking Back, Looking Ahead: Chartbook on Women’s Progress Ariane Hegewisch Jeff Hayes Jessica Milli Elyse Shaw Heidi Hartmann Institute for Women’s Policy Research Acknowledgments We would like to thank the following members of the AARP Public Policy Institute and AARP’s Office of Policy Integration for their contributions to this paper: Lori Trawinski, Sara Rix, Donald Redfoot, Christina Fitzpatrick, Gary Koenig, Mikki Waid, Alison Shelton, and Julia Alexis. Also, we would like to thank Allison Porter for her assistance as well as an external, anonymous peer reviewer for their time and valuable contributions. AARP’s Public Policy Institute informs and stimulates public debate on the issues we face as we age. Through research, analysis, and dialogue with the About the Future of Work@50+ nation’s leading experts, PPI promotes development of sound, creative policies This report is part of the Future of Work@50+ Initiative. to address our common need for This is a multiyear initiative that examines the challenges economic security, health care, and and opportunities facing older workers. For other reports and quality of life. information, visit: http://www.aarp.org/futureofwork. The views expressed herein are for information, debate, and discussion, and do not necessarily represent official policies of AARP. LOOKING BACK, LOOKING AHEAD: CHARTBOOK ON WOMEN’S PROGRESS i Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ..............................................................................................................................................i -

NAEP 2008 Trends in Academic Progress

Institute of Education Sciences U.S. Department of Education NCES 2009–479 NAEP 2008 Trends in Academic Progress READING 1971–2008 MATHEMATICS 1973–2008 CONTENTS Executive Summary 2 Executive Summary 6 Introduction This report presents the results of the NAEP long- 8 The Long-Term Trend Assessment term trend assessments in reading and mathemat- in Reading ics, which were most recently given in the 2007–08 28 The Long-Term Trend Assessment school year to students at ages 9, 13, and 17. Nationally representative samples of over 26,000 in Mathematics public and private school students were assessed 50 Technical Notes in each subject area. 53 Appendix Tables The long-term trend assessments make it possible to chart educational progress since the early 1970s. Results in reading are available for 12 assessments going back to the rst in 1971. The rst of 11 assess- ments in mathematics was administered in 1973. What is Throughout this report, the most recent results are compared to those from 2004 and from the rst year The Nation’s the assessment was conducted. ™ Report Card ? The original assessment format, content, and proce- dures were revised somewhat in 2004 to update content The Nation’s Report Card™ informs the public about and provide accommodations to students with disabili- the academacademicic achachievementievement ooff elementarelementaryy and ties and English language learners. The knowledge and secondary students in the United StatesStates. Report skills assessed, however, remain essentially the same cards communicate the findings of the National since the rst assessment year. Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a continuing and nationally representative measure Improvements seen in reading and of achievement in various subjects over time. -

Developing Achievement Levels on the National Assessment of Educational Progress for Writing Grades 8 and 12 in 2011 and Grade 4 in 2013

National Assessment Governing Board Developing Achievement Levels on the National Assessment of Educational Progress for Writing Grades 8 and 12 in 2011 and Grade 4 in 2013 Submitted to: Dr. Susan Loomis National Assessment Governing Board 800 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 825 Washington, DC 20002-4233 Email: [email protected] Phone: 202.357.6940 This study was funded by the National Assessment Governing Board under Contract ED-NAG-10-C-0003. Submitted by: Measured Progress 100 Education Way Dover, NH 03820 Phone: 603.749.9102 NAEP Writing ALS Design Document March 10, 2011 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 Purpose of This Document ................................................................................. 5 Organization of This Document ......................................................................... 6 Methodology ............................................................................................................ 7 Body of Work ...................................................................................................... 7 BoW Technological Integration and Enhancements (BoWTIE) ..................... 10 Research Studies ..................................................................................................... 13 Field Trial .......................................................................................................... 13 Hardware .................................................................................................... -

FP2020 the ARC of PROGRESS 2019–2020 Cover Photo by Jonathan Torgovnik/ Getty Images/Images of Empowerment

FP2020 THE ARC OF PROGRESS 2019–2020 COVER PHOTO BY Jonathan Torgovnik/ Getty Images/Images of Empowerment THE FP2020 PROGRESS REPORT IS DIGITAL THIS YEAR. The full report is online at familyplanning2020.org/progress. fp2030.org This condensed print version contains only the material facebook.com/FP2030Global our partners find most useful to have in print. It includes @FP2030Global highlights, previews of the online content, the financial #FP2030Progress report, and data analysis. Everything else is digital. FP2020 THE ARC OF PROGRESS 2019–2020 Condensed Print Version TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................ 4 SECTION 03 PARTNERSHIP ......................................... 32 SECTION 01 THE ARC OF PROGRESS ..........................10 SECTION 04 FINANCE ................................................. 36 SECTION 02 FAMILY PLANNING SECTION 05 IN THE TIME OF COVID ........................... 24 MEASUREMENT ....................................... 48 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In the eight years of the FP2020 partnership, the family planning community has proven that when we work together, across borders and sectors, we can truly change the course of progress on family planning. Family Planning 2020 was launched with a simple premise: that every woman and girl, no matter where she lives, should have the opportunity to use lifesaving, life-changing modern contraception. The leaders who gathered at the London Summit in 2012 agreed on an ambitious goal and a tight timeframe for achieving it: to reach an additional 120 million users of modern contraception in the world’s 69 lowest-income countries by 2020. That initial eight-year period is now drawing to a close. We didn’t reach 120 million, but we did bend the curve of progress upward. The FP2020 initiative has become a movement, with more than 130 governments, foundations, multilaterals, civil society organizations, youth-led organizations, and private sector partners all collaborating to advance rights- based family planning. -

Part 2 Almaz, Salyut, And

Part 2 Almaz/Salyut/Mir largely concerned with assembly in 12, 1964, Chelomei called upon his Part 2 Earth orbit of a vehicle for circumlu- staff to develop a military station for Almaz, Salyut, nar flight, but also described a small two to three cosmonauts, with a station made up of independently design life of 1 to 2 years. They and Mir launched modules. Three cosmo- designed an integrated system: a nauts were to reach the station single-launch space station dubbed aboard a manned transport spacecraft Almaz (“diamond”) and a Transport called Siber (or Sever) (“north”), Logistics Spacecraft (Russian 2.1 Overview shown in figure 2-2. They would acronym TKS) for reaching it (see live in a habitation module and section 3.3). Chelomei’s three-stage Figure 2-1 is a space station family observe Earth from a “science- Proton booster would launch them tree depicting the evolutionary package” module. Korolev’s Vostok both. Almaz was to be equipped relationships described in this rocket (a converted ICBM) was with a crew capsule, radar remote- section. tapped to launch both Siber and the sensing apparatus for imaging the station modules. In 1965, Korolev Earth’s surface, cameras, two reentry 2.1.1 Early Concepts (1903, proposed a 90-ton space station to be capsules for returning data to Earth, 1962) launched by the N-1 rocket. It was and an antiaircraft cannon to defend to have had a docking module with against American attack.5 An ports for four Soyuz spacecraft.2, 3 interdepartmental commission The space station concept is very old approved the system in 1967. -

Module 3 Slide Handouts

Pathways of Progress™ Module 3: The Logic Behind Pathways of Progress TM Three Guiding Principles in Establishing Pathways of Progress Matter Individual Student Learning Goals • We know that the level of skills for a student at the Meaningful. beginning of the year is an important predictor of their – Goals should support students to achieve meaningful outcomes or increase the likelihood of achieving meaningful and important end of year outcome (partial eta squared = 71%). outcomes. • Pathways of Progress contributes to initial skills in Ambitious. predicting later outcomes (partial eta squared = 17%). – Above typical or well above typical progress are ambitious goals. – Typical progress may be sufficient for students who are at or above benchmark – Typical progress may not be adequate for students who are likely to need additional support to achieve benchmark goals. – Below typical or well below typical progress are just not very ambitious. Attainable. – High in the well above typical range is probably not attainable. – Typical and above typical progress is readily attainable. – Well below typical and below typical progress may be attainable, but are not ambitious or meaningful. Pathways of ProgressTM ©2015 Dynamic Measurement Group 33 Pathways of ProgressTM ©2015 Dynamic Measurement Group 34 Considerations in Establishing Considerations in Establishing Student Learning Goals Student Learning Goals DIBELS Next informed considerations: Other considerations: What rate of progress is above typical progress What rate of progress is possible with a very compared to other students with similar initial skills? effective, research based intervention? What rate of progress is necessary to narrow the What resources are available to support instruction achievement gap with students making adequate and intervention? progress? What is the student attendance pattern? What rate of progress is necessary to achieve important benchmark goals. -

Mir Hardware Heritage Index

Mir Hardware Heritage Index A attitude control systems (continued) on Kvant 2 165 Aktiv docking unit. See docking systems: Aktiv on Mir 106, 119, 123, 131, 137 Almaz (see also military space stations) on Original Soyuz 157, 168-169, 187 hardware adaptation to Salyut 69, 71 on Salyut 1 67 history 63-65 on Salyut 6 75, 79, 81, 84-85 missions 177-178 on Salyut 7 91, 100, 185 in station evolution 1, 62, 154-156 on Soyuz 1 10 system tests 70 on Soyuz Ferry 24-25 Almaz 1 64, 65, 68, 177 on Soyuz-T 47, 50 Almaz 1V satellite 65 on space station modules 155 on TKS vehicles 159 Almaz 2 64, 65, 68, 73, 177, 178 on Zond 4 14 Almaz 3 64, 73, 178 Almaz 4 64 Altair/SR satellites B description 105 berthing ports 76, 103, 105, 165 illustration 106 BTSVK computer 47 missions 108, 109, 113, 115, 118, 121, 133, 139 Buran shuttle androgynous peripheral assembly system (APAS). See crews 51, 54, 98 docking systems: APAS-75; APAS-89 flights 115, 188, 193 Antares mission 136 hardware adapted to Polyus 168 APAS. See docking systems: APAS-75; APAS-89 illustration 189 Apollo program (U.S.) (see also Apollo Soyuz Test and Mir 107, 167 Project) and Salyut 7 161 command and service module (CSM) 5, 6, 16, 172, 173, 176, 177 illustration 176 C lunar module (LM) 19, 21, 172 circumlunar flight 3, 4, 5, 12, 63, 155, 173, 175 (see illustration 175 also lunar programs) missions 172, 173, 175-178 Cosmos 133 10, 171 Apollo Soyuz Test Project (ASTP) (see also ASTP Soyuz) Cosmos 140 10, 172 background 6, 65 Cosmos 146 14, 172 mission 28, 34-35, 177-178 Cosmos 154 14, 172 and Soyuz 18 72 Cosmos 186 10-11, 172 approach systems. -

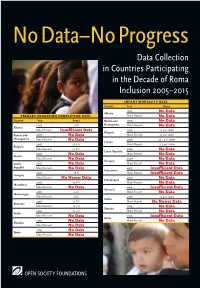

No Data No Progress

No Data–No Progress Data Collection in Countries Participating in the Decade of Roma Inclusion 2005–2015 INFANT MORTALITY RATE Country Year Roma 2005 No Data Albania PRIMARY EDUCATION COMPLETION RATE Most Recent No Data Country Year Roma Bosnia and 2005 No Data 2005 14% Herzegovina Most Recent No Data Albania Most Recent Insuffi cient Data 2005 25 per 1000 Bulgaria Bosnia and 2005 No Data Most Recent 25 per 1000 Herzegovina Most Recent No Data 2005 25.1 per 1000 Croatia 2005 28.3% Most Recent 11.5 per 1000 Bulgaria Most Recent 31.6% 2005 No Data Czech Republic 2005 No Data Most Recent No Data Croatia Most Recent No Data 2005 No Data Hungary Czech 2005 No Data Most Recent No Data Republic Most Recent No Data 2005 Insuffi cient Data Macedonia 2005 76% Most Recent Insuffi cient Data Hungary Most Recent No Newer Data 2005 No Data Montenegro 2005 50.8% Most Recent No Data Macedonia Most Recent No Data 2005 Insuffi cient Data Romania 2005 9.2% Most Recent No Data Montenegro Most Recent 20% 2005 25 per 1000 Serbia 2005 31.7% Most Recent No Newer Data Romania Most Recent 19.7% 2005 No Data Slovakia 2005 22.7% Most Recent No Data Serbia Most Recent No Data 2005 Insuffi cient Data Spain 2005 No Data Most Recent No Data Slovakia Most Recent No Data 2005 No Data Spain Most Recent No Data OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS No Data—No Progress Data Collection in Countries Participating in the Decade of Roma Inclusion 2005–2015 No Data—No Progress Data Collection in Countries Participating in the Decade of Roma Inclusion 2005–2015 June 2010 Roma Initiatives OPEN SOCIETY FOUNDATIONS Copyright © 2010 by the Open Society Institute. -

Crop Progress - State Stories

Crop Progress - State Stories ISSN: 2470-9816 Released March 31, 2020, by the National Agricultural Statistics Service (NASS), Agricultural Statistics Board, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). ALABAMA: Average temperatures ranged from 2.4 to 14.5 degrees warmer than historical values. Total rainfall for the month ranged from trace amounts of rain to 11.1 inches in Limestone County. According to the U.S. Drought Monitor, the State remained drought free throughout the month. Most of the State was affected by heavy rains throughout the month, delaying field preparations for many. In areas where rain slowed down later in the month, corn was planted, cotton and peanut fields had lime and fertilizer applied, and hay was being chemically burned for the new hay season. Herbicide and fertilizer applications for wheat were delayed due to excessive rain and flooding throughout the month. Some wheat fields were still under water, but starting to recover. The wheat crop was rated in fair to excellent condition, overall. Pastures were greening, but not fast enough for cattlemen that were at the end of their hay supplies and needing relief. However, cattle were still in good condition. Vegetable planting had begun and the strawberry crop was looking good. ALASKA: DATA NOT AVAILABLE ARIZONA: This report for Arizona is for the week ending Sunday, March 29, 2020. By the end of this week, 98 percent of Durum wheat has emerged, according to the Mountain Regional Field Office of the National Agricultural Statistics Service, USDA. Thirty-five percent has headed compared with 22 percent last year. Durum wheat conditions were rated mostly excellent. -

Progress 6 Spaces Progress 6 Spaces. Progress 4 Spaces

ds You did not reduce your cholesterol by There it is — you’re smoking cigarettes 30%, now the doctor is getting stern: again and the pain in your chest she gave you a prescription for 2 indicates you have damaged your ocar medications but you never filled the coronary arteries! her prescription. t 2 2 A 2 Progress 6 spaces. 1. Progress 6 spaces 2. ® ® ZONE Positively Aging /M. O. R. E. ZONE Positively Aging /M. O. R. E. 2006©The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio 2006©The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio ZONE You quit smoking. Your doctor is concerned because C-reactive protein in your blood is too high, indicating that inflammation is happening somewhere in your body. In your case, it’s in the arteries leading to 2 2 your heart! 3. 4. Regress 1 space. Progress 4 spaces. ® ® ZONE Positively Aging /M. O. R. E. ZONE Positively Aging /M. O. R. E. 2006©The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio 2006©The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio You like to eat fries and burgers in If you are male, spite of the high sodium and cholesterol; so again, you abandon Progress 6 spaces. your healthy eating plan. If you are female, 2 2 5. Do Not Progress 6. Progress 3 spaces or Regress. ® ® ZONE Positively Aging /M. O. R. E. ZONE Positively Aging /M. O. R. E. 2006©The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio 2006©The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio Instead of taking the escalator to the Your doctor just told you your blood second floor, you decide to take the sugar is too high (again). -

How Do Pupils Progress During Key Stages 2 and 3?

Research Report DFE-RR096 How do pupils progress during Key Stages 2 and 3? Education Standards Analysis and Research Division Department for Education Executive Summary What’s in this Report? How do Pupils Progress During Key Stages 2 and 3? presents statistical analysis of pupils’ progress in reading, writing and maths during years 3-9, based on a sample of termly teacher assessments for over 70,000 pupils in 10 Local Authorities. The main issues addressed are when most progress is made, who makes most progress, how termly progress adds up to expected threshold levels of achievement, and what progress through National Curriculum Key Stages 2 and 3 looks like empirically – the patterns and pathways actually followed by pupils. What are the Key Findings from the Analysis? Learning Pathways (details in Chapter 5) • For many pupils, progress during Key Stages 2 and 3 is not linear and continuous; episodes of regression to an earlier level of attainment, or remaining at the same level for a period, are part of the norm. • Patterns of progress are highly individual; there is low concentration of pupils into one pathway or another, especially in reading and writing. • The more progress a pupil made in the previous term, the less likely they are to make progress the following term, and vice versa. Timing of Progress (details in Chapter 1) • More progress is made per year in Key Stage 2 than Key Stage 3 in all three subjects, but especially in reading and writing. • Pupils make most progress during the summer term and least progress during the autumn term. -

This Report Covers Updates to Cleveland

First Quarter 2019 Vision Report Current Reporting Date: Jul 15, 2019 Report Created On: May 07, 2019 Page 1 Report Legend No Update Overdue # Priority Page 2 Plan Summary Vision 1 Progress 50% Vision 2 Progress 53% Owner: Tanisha Briley Owner: Tanisha Briley % # % # On Track 83.33 20 Status Pending 4.76 1 Completed 16.67 4 On Track 47.62 10 Status Status Upcoming 9.52 2 Completed 38.1 8 Goal: 5 Action: 24 Goal: 6 Action: 21 Vibrant Neighborhoods Cleveland Heights will be a city of strong, safe, Complete Transportation Network Cleveland Heights will be a and vibrant neighborhoods composed of a variety of beautiful homes community where getting to work, meeting friends over dinner, or and buildings, well-maintained yards and greenspaces, historic shopping can be accomplished easily by foot, bike, transit, or car districts, active neighbo... along beautiful and well-maintained... Vision 3 Progress 37% Vision 4 Progress 57% Owner: Tanisha Briley Owner: Tanisha Briley % # % # Status Pending 7.14 1 On Track 66.67 10 On Track 71.43 10 Completed 33.33 5 Status Upcoming 7.14 1 Status Completed 14.29 2 Goal: 5 Action: 14 Goal: 5 Action: 15 Environmentally Sustainable Community Cleveland Heights will be an Business Friendly Cleveland Heights will be a business-friendly environmentally sustainable community that uses green community that leverages the city’s entrepreneurial spirit, well- infrastructure to capture and slow stormwater, encourages active educated population, solid services, strong infrastructure, and transportation, and promotes state