Measuring Student Progress a State-By-State Report Card

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Work Orders in Progress

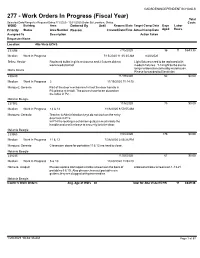

GADSDEN INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS 277 - Work Orders In Progress (Fiscal Year) Total Selected Date Range for Request Dates:7/1/2020 - 12/31/2020 Order By Location, Status Costs WOID Building Area Deferred By Until Request Date Target Comp Date Days Labor Priority Status Area Number Reason Created Date/Time Actual Comp Date Aged Hours Assigned To Description Action Taken Requester Name Location: Alta Vista ECHS 233356 7/15/2020 36 11 $649.38 Medium Work In Progress 7/15/2020 11:35:35 AM 8/20/2020 Tellez, Hector Replaced bulbs in girls restrooms and 2 fixtures did not Light fixtures need to be replaced with work needs ballast modern fixtures. T-12 light bulbs are no longer ordered or carried by warehouse. Maria Davila Please forwarded to Electrician 238220 11/19/2020 62 $0.00 Medium Work In Progress 2 11/19/2020 11:14:15 Marquez, Gerardo Part of the door mechanism fell out the door handle in P2; please reinstall. The pieces have been placed on the table in P2. Melanie Beegle 237972 11/6/2020 75 $0.00 Medium Work In Progress 12 & 14 11/6/2020 8:50:55 AM Marquez, Gerardo Teacher & Administration keys do not work on the entry door lock in P12. In P14 the locking mechanism gets jammed inside the handle and won't release to securely lock the door. Melanie Beegle 233863 7/28/2020 176 $0.00 Medium Work In Progress 11 & 13 7/28/2020 2:05:26 PM Marquez, Gerardo Classroom doors for portables 11 & 13 are hard to close. -

A Framework for Measuring Australian Higher

A FRAMEWORK FOR MEASURING EQUITY PERFORMANCE IN AUSTRALIAN HIGHER EDUCATION Draft Framework Document V1.6 Tim Pitman and Paul Koshy, November 2014 Make tomorrow better. ncsehe.edu.au A Framework for Measuring Equity Performance in Australian Higher Education – Draft Framework Document Contents Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Abbreviations and Acronyms ................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 6 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 8 2. Overview of the Equity Performance Framework for Australian Higher Education ........ 10 Tier 1: Context (Pre-higher education) ............................................................................................ 11 Tier 2: Performance (Higher education) .......................................................................................... 12 Tier 3: Outcome (Post-higher education) ....................................................................................... 12 Comparisons by State and Territory ................................................................................................ 13 Comparisons with the General -

NAEP 2008 Trends in Academic Progress

Institute of Education Sciences U.S. Department of Education NCES 2009–479 NAEP 2008 Trends in Academic Progress READING 1971–2008 MATHEMATICS 1973–2008 CONTENTS Executive Summary 2 Executive Summary 6 Introduction This report presents the results of the NAEP long- 8 The Long-Term Trend Assessment term trend assessments in reading and mathemat- in Reading ics, which were most recently given in the 2007–08 28 The Long-Term Trend Assessment school year to students at ages 9, 13, and 17. Nationally representative samples of over 26,000 in Mathematics public and private school students were assessed 50 Technical Notes in each subject area. 53 Appendix Tables The long-term trend assessments make it possible to chart educational progress since the early 1970s. Results in reading are available for 12 assessments going back to the rst in 1971. The rst of 11 assess- ments in mathematics was administered in 1973. What is Throughout this report, the most recent results are compared to those from 2004 and from the rst year The Nation’s the assessment was conducted. ™ Report Card ? The original assessment format, content, and proce- dures were revised somewhat in 2004 to update content The Nation’s Report Card™ informs the public about and provide accommodations to students with disabili- the academacademicic achachievementievement ooff elementarelementaryy and ties and English language learners. The knowledge and secondary students in the United StatesStates. Report skills assessed, however, remain essentially the same cards communicate the findings of the National since the rst assessment year. Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), a continuing and nationally representative measure Improvements seen in reading and of achievement in various subjects over time. -

The Evaluation of the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) “New Business Model”

AUSTRALIAN COUNCIL OF TESOL ASSOCIATIONS SUBMISSION TO The Evaluation of the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) “new business model” March-April 2019 CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 RECOMMENDATIONS 9 Introduction 13 1. The goals of the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) 14 2. The goals of the Skills for Employment and Education (SEE) Program 16 3. Where does the AMEP belong? 18 4. Targeted Tuition Streams (requirement 1a) 20 4.1 Rationale 20 4.2 Overlap between the AMEP pre-employment stream and the SEE Program 23 4.3 ACTA Recommendations on streaming in the AMEP 23 5. Extra tuition hours - the Special Preparatory Program (SPP) and AMEP Extend (requirements 1b & c) 23 5.1 The SPP 23 5.2 AMEP Extend 26 6. Assessment – use of the Australian Core Skills Framework (ACSF) as a benchmark and to align the AMEP and SEE Program (requirements 1e and 4) 28 6.1 The stated rationale for mandating the ACSF 28 6.2 The ACIL Allen recommendation 29 6.3 The ACSF as “a tool for measuring language proficiency” 31 6.3.1 The ACSF: is it reliable? Implications for its role as the basis for a KPI 32 6.3.2 The ACSF: is it a valid tool for assessing English language proficiency and progress? 34 6.4 The ISLPR 38 6.5 The ACSF – facilitating greater [sic] pathways between the AMEP and other training programs and the tertiary education sector 41 6.6 Use of the ACSF in aligning the AMEP and SEE Program 43 7. Performance management (requirement 1f) 46 7.1 Engagement 47 7.1.1 Continuous enrolment/rolling intakes 47 7.1.2 Monitoring attendance and accounting for absences. -

Northern Territory Department of Education Submission

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Northern Territory Department of Education Submission Inquiry into the Education of Students in Remote and Complex Environments The Northern Territory (NT) Department of Education seeks to provide a submission to the inquiry into the education of students in remote and complex environments, commissioned by the Standing Committee on Employment, Education and Training. The submission aims to highlight the unique circumstances experienced by students in NT remote and very remote communities and how the department is adapting its service delivery, using innovative approaches, to meet their needs. The NT Government recognises the critical role of culture, family, community and country in delivering better outcomes, particularly for Aboriginal people. There are a number of initiatives underway that target these core factors while balancing the complexities of delivering government services in remote and very remote communities. Remote and very remote Territory context The NT is the most remote jurisdiction in Australia, with approximately 245 000 people spread across one sixth of Australia’s land mass. Over 40 per cent of the population is considered to live in remote or very remote areas. The overwhelming majority of residents living in remote communities are Aboriginal Territorians, with a much younger population on average than other parts of Australia. Unemployment is high and there are significant health issues. Fifty-four per cent of remote households and 12 per cent of very remote communities speak English in the home. Most children attending school in remote or very remote communities only speak English at school, not in their community or in their home. The transitional nature of community life, and movement of families between communities can be disruptive to a child’s education, particularly when this movement occurs across multiple jurisdictions, such as the NT, Western Australia and South Australia borders. -

Constructing the Australian School History Curriculum: Ideology, High Politics and the History Wars in the Howard Years

Chapter 2 Constructing the Australian School History Curriculum: Ideology, High Politics and the History Wars in the Howard Years Tony Taylor This chapter is a substantially revised and expanded version of a keynote address “Disputed Territory: Who Owns History in Schools?” given at the Australian National University Research School of Social Sciences’ conference “Governing by looking back” 12–14 December (2007). The relevant official government papers for the summit, including an edited transcript of proceedings, have been archived on the Department of Employment Education and Workplace Relations website at http://www.dest.gov.au/sectors/school_education/ policy_initiatives_reviews/key_issues/Australian_History/ (as at July 2009) 2.1 Background to Policy and History Curriculum In 1996, a Liberal/National conservative coalition was victorious in the Australian March general election and coalition leader, John Howard, became the nation’s 25th prime minister. Howard’s accession, bolstered by a large majority, came following his own long and difficult political apprenticeship and after 13 years of Labour federal government. Although focused throughout his next three administrations on the big political issue including race relations, immigration policy, Middle East conflict, privatisation and industrial relations, Howard still kept time for history, which, after small beginnings, began to loom increasingly large in the prime minister’s con- sciousness. This incipient public attention to history began in 1996 in his Sir Thomas Playford memorial speech where he accused “cultural dieticians in our midst” of attempting to “rewrite Australian history in the service of a partisan political cause.”1 His comments were aimed at academics and others who favoured what had already been referred to by conservatively inclined historian Geoffrey Blainey as the “black armband” view of Australia’s past. -

Developing Achievement Levels on the National Assessment of Educational Progress for Writing Grades 8 and 12 in 2011 and Grade 4 in 2013

National Assessment Governing Board Developing Achievement Levels on the National Assessment of Educational Progress for Writing Grades 8 and 12 in 2011 and Grade 4 in 2013 Submitted to: Dr. Susan Loomis National Assessment Governing Board 800 North Capitol Street, NW, Suite 825 Washington, DC 20002-4233 Email: [email protected] Phone: 202.357.6940 This study was funded by the National Assessment Governing Board under Contract ED-NAG-10-C-0003. Submitted by: Measured Progress 100 Education Way Dover, NH 03820 Phone: 603.749.9102 NAEP Writing ALS Design Document March 10, 2011 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 Purpose of This Document ................................................................................. 5 Organization of This Document ......................................................................... 6 Methodology ............................................................................................................ 7 Body of Work ...................................................................................................... 7 BoW Technological Integration and Enhancements (BoWTIE) ..................... 10 Research Studies ..................................................................................................... 13 Field Trial .......................................................................................................... 13 Hardware .................................................................................................... -

International Comparative Study: the Australian Curriculum and the Singapore Curriculum

INTERNATIONAL COMPARATIVE STUDY: THE AUSTRALIAN CURRICULUM AND THE SINGAPORE CURRICULUM © Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) 2018 This work is copyright. You may only download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal non-commercial educational use or non-commercial educational use within your organisation. All other rights are reserved. Requests and enquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: ACARA Copyright Administration Level 10 255 Pitt Street Sydney NSW 2000 [email protected] 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................4 1 PROGRAM OF RESEARCH .............................................................8 1.1 Background ....................................................................................................................... 8 1.2 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 8 2 CONTEXTUAL DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS ........................... 14 2.1 Preamble ......................................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Demographic comparison: Australia and Singapore ........................................................ 15 2.3 Curriculum design principles and purpose ....................................................................... 31 2.3.1 Education Policy ...................................................................................................... -

Navitas Submission

Submission: Draft National Strategy for International Education About Navitas Navitas Ltd is an Australian global education partner providing pre-university and university programs, English language courses, migrant education and settlement services, creative media education, student recruitment, professional development and corporate training services to more than 80,000 students across a network of over 120 colleges and campuses in 27 countries. Navitas listed on the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) in 2004 and is now an S&P/ASX Top 100 Company, employing more than 5,800 staff globally. General comments Navitas commends the Government for: Responding positively to, and adopting, all the recommendations of the report of the International Education Advisory Council, chaired by Michael Chaney AO, Australia – Educating Globally. Recognising the critical importance of international education to Australia, developing a national vision, strategy and approach, and establishing ‘a ministerially led coordinating council for international education’. Developing a 10-year market development strategy, Australia International Education 2025, to inform, support and focus investment and actions in delivering on the national strategy. Consulting with the international education sector, business and industry, and communities on the development of the strategies and their implementation. Navitas welcomes the support given by various levels of government to international and transnational education, and the recognition by governments of the contribution the international education sector makes to economies and societies, both in Australia and globally. In the Strategic Actions we endorse the progress that is being made on a whole of government effort, including current reviews and consultations into the student visa framework, ESOS Act and National Code, all of which are integral to an integrated regulatory and support framework for the sector. -

First Quarter Strategic Plan Update

FIRST QUARTER STRATEGIC PLAN UPDATE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 4 OVERALL PROGRESS .............................................................................................................................. 4 HIGHLIGHTS .............................................................................................................................................. 5 SMALL BUSINESS PROGRAM ....................................................................................................................... 5 COMPREHENSIVE PLAN ............................................................................................................................... 5 FIVE-YEAR FINANCIAL PLAN/MODEL ......................................................................................................... 5 UTILITY RATES ........................................................................................................................................... 6 GREEN RIBBON BEAUTIFICATION ................................................................................................................ 6 ANNA LIBRARY ........................................................................................................................................... 6 WHAT’S NEXT ............................................................................................................................................ 7 GOAL 1: GROWING -

FP2020 the ARC of PROGRESS 2019–2020 Cover Photo by Jonathan Torgovnik/ Getty Images/Images of Empowerment

FP2020 THE ARC OF PROGRESS 2019–2020 COVER PHOTO BY Jonathan Torgovnik/ Getty Images/Images of Empowerment THE FP2020 PROGRESS REPORT IS DIGITAL THIS YEAR. The full report is online at familyplanning2020.org/progress. fp2030.org This condensed print version contains only the material facebook.com/FP2030Global our partners find most useful to have in print. It includes @FP2030Global highlights, previews of the online content, the financial #FP2030Progress report, and data analysis. Everything else is digital. FP2020 THE ARC OF PROGRESS 2019–2020 Condensed Print Version TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................ 4 SECTION 03 PARTNERSHIP ......................................... 32 SECTION 01 THE ARC OF PROGRESS ..........................10 SECTION 04 FINANCE ................................................. 36 SECTION 02 FAMILY PLANNING SECTION 05 IN THE TIME OF COVID ........................... 24 MEASUREMENT ....................................... 48 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In the eight years of the FP2020 partnership, the family planning community has proven that when we work together, across borders and sectors, we can truly change the course of progress on family planning. Family Planning 2020 was launched with a simple premise: that every woman and girl, no matter where she lives, should have the opportunity to use lifesaving, life-changing modern contraception. The leaders who gathered at the London Summit in 2012 agreed on an ambitious goal and a tight timeframe for achieving it: to reach an additional 120 million users of modern contraception in the world’s 69 lowest-income countries by 2020. That initial eight-year period is now drawing to a close. We didn’t reach 120 million, but we did bend the curve of progress upward. The FP2020 initiative has become a movement, with more than 130 governments, foundations, multilaterals, civil society organizations, youth-led organizations, and private sector partners all collaborating to advance rights- based family planning. -

2020-2021 Hays CISD Academic Calendar

>> Amended School Calendar for COVID-19 Response << HAYS CISD 2020 – 2021 AMENDED CALENDAR 3 Student/ Staff Holiday JULY 2020 JANUARY 2021 1 Student/ Staff Holiday 4 Staff Development & Prep S M T W Th F S S M T W Th F S /Student Holiday 1 2 3 4 1 2 15 Asynchronous/Virtual Learning Day 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 18 Student/ Staff Holiday 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 27-28 Early Release High School Only/ Finals 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 29 Early Release 6th – 12th 2929]] Grades/ Finals 0 D / 0 E / 0 M / 0 H 26 27 28 29 30 31 24 25 26 27 28 30 29 Grading Period/UIL 31 Eligibility Cut-Off Date 18 D / 8,370 E / 8,322 M / 8,025 H 27 & 28 Flexible Staff Days/ Staff AUGUST 2020 FEBRUARY 2021 1 Third 9-Week Grading Development Period Begins (Required teacher contract S M T W Th F S S M T W Th F S 12 Asynchronous/Virtual days, but can be scheduled 1 [1 2 3 4 5 6 Learning Day on other dates.) 31 Staff Development/Prep 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 15 Staff Development/ 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 14 15* 16 17 18 19 20 Student Holiday 15* Weather Make Up Day 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Will be used as Asynchronous/ 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 28 Virtual Learning Day 0 D / 0 E / 0 M / 0 H 30 31 19 D / 8,835 E / 8,854 M / 8,930 H 1 - 4 Staff Development/Prep SEPTEMBER 2020 MARCH 2021 12 Asynchronous/Virtual 7 Student/ Staff Holiday Learning Day 8 First Day of School/ First S M T W Th F S S M T W Th F S 15-19 Student/ Staff Holidays 9-Week Grading Period 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 6 7 [8 9 10 11 12 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 13 14