Society and Economy During Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: an Archaeological Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5. from Janapadas to Empire

MODULE - 1 Ancient India 5 Notes FROM JANAPADAS TO EMPIRE In the last chapter we studied how later Vedic people started agriculture in the Ganga basin and settled down in permanent villages. In this chapter, we will discuss how increased agricultural activity and settled life led to the rise of sixteen Mahajanapadas (large territorial states) in north India in sixth century BC. We will also examine the factors, which enabled Magadh one of these states to defeat all others to rise to the status of an empire later under the Mauryas. The Mauryan period was one of great economic and cultural progress. However, the Mauryan Empire collapsed within fifty years of the death of Ashoka. We will analyse the factors responsible for this decline. This period (6th century BC) is also known for the rise of many new religions like Buddhism and Jainism. We will be looking at the factors responsible for the emer- gence of these religions and also inform you about their main doctrines. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to explain the material and social factors (e.g. growth of agriculture and new social classes), which became the basis for the rise of Mahajanapada and the new religions in the sixth century BC; analyse the doctrine, patronage, spread and impact of Buddhism and Jainism; trace the growth of Indian polity from smaller states to empires and list the six- teen Mahajanapadas; examine the role of Ashoka in the consolidation of the empire through his policy of Dhamma; recognise the main features– administration, economy, society and art under the Mauryas and Identify the causes of the decline of the Mauryan empire. -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title Mahajanapadas- Rise of Magadha – Nandas – Invasion of Alexander Module Id I C/ OIH/ 08 Pre requisites Early History of India Objectives To study the Political institutions of Ancient India from earliest to 3rd Century BCE. Mahajanapadas , Rise of Magadha under the Haryanka, Sisunaga Dynasties, Nanda Dynasty, Persian Invasions, Alexander’s Invasion of India and its Effects Keywords Janapadas, Magadha, Haryanka, Sisunaga, Nanda, Alexander E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Sources Political and cultural history of the period from C 600 to 300 BCE is known for the first time by a possibility of comparing evidence from different kinds of literary sources. Buddhist and Jaina texts form an authentic source of the political history of ancient India. The first four books of Sutta pitaka -- the Digha, Majjhima, Samyutta and Anguttara nikayas -- and the entire Vinaya pitaka were composed between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. The Sutta nipata also belongs to this period. The Jaina texts Bhagavati sutra and Parisisthaparvan represent the tradition that can be used as historical source material for this period. The Puranas also provide useful information on dynastic history. A comparison of Buddhist, Puranic and Jaina texts on the details of dynastic history reveals more disagreement. This may be due to the fact that they were compiled at different times. Apart from indigenous literary sources, there are number of Greek and Latin narratives of Alexander’s military achievements. They describe the political situation prevailing in northwest on the eve of Alexander’s invasion. -

Intricacy of Certain Verses of Āryabhatīya and Jain Tradition

Intricacy of Certain Verses of Āryabhat ī ya and Jain Tradition – Identification of Asmaka as Sravanabelgola-Camravattam Jain Country K. Chandra Hari ƒ Abstract The conclusions that got derived from astronomical considerations about the homeland of Ārybhat a viz Camravattam (10N51, 75E45) is shown to receive additional support from the socio-cultural factors related to the Jaina tradition in Kerala and South India. It is shown that the A śmaka referred to by Bh āskara-I is the South Indian Jain settlement around Sravan abelgol a (12N51, 76E29) and Dharmasthala (12N53, 75E23) – place receiving the name A śmaka in Jaina canons because of the great stone monoliths at the place. A number of circumstantial evidences have been adduced in support of the above conclusions: (a) Verse 9 of K ālakriy ā giving the Jaina 12 fold division of Yuga (b) Verse 5 of Da śag ītik ā which speaks of Bharata, the first Universal emperor of Jains who accessed the throne from the Ādin ātha R s abhadeva at the beginning of Apasarpin ī Kaliyuga. Āryabhat a’s rejection of the 4:3:2:1 cycle of Kr t ādi yugas based on the Smr tis provide attestation to the new interpretation attempted of the verse (c) Verse 11 of Gol a referring to Nandana-vana and Meru represents terminology borrowed from Tiloyapan n atti of Jains (d) References to Bramah the primordial deity of Jains in verses 1 of Gan it ā and 49, 50 of Gol a (e) Use of Kali Era having the distinct signature of Aryabhata for the first time in South India with the Aihole inscription of the C ālukya King Pulike śi-II. -

Unit 1 Reconstructing Ancient Society with Special

Harappan Civilisation and UNIT 1 RECONSTRUCTING ANCIENT Other Chalcolithic SOCIETY WITH SPECIAL Cultures REFERENCE TO SOURCES Structure 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Sources 1.1.1 Epigraphy 1.1.2 Numismatics 1.1.3 Archaeology 1.1.4 Literature 1.2 Interpretation 1.3 The Ancient Society: Anthropological Readings 1.4 Nature of Archaeology 1.5 Textual Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Glossary 1.8 Exercises 1.0 INTRODUCTION The primary objective of this unit is to acquaint the learner with the interpretations of the sources that reveal the nature of the ancient society. We therefore need to define the meaning of the term ‘ancient society’ to begin with and then move on to define a loose chronology in the context of the sources and their readings. It would also be useful to have an understanding about the various readings of the sources, a kind of a historiography of the interpretative regime. In order to facilitate a better understanding this unit is divided into five sections. In the introduction we have discussed the range of interpretations that are deployed on the sources and often the sources also become interpretative in nature. The complexity of the sources has also been dealt with in the same context. The new section then discusses the ancient society and what it means. This discussion is spread across the regions and the varying sources that range from archaeology to oral traditions. The last section then gives some concluding remarks. 1.1 SOURCES Here we introduce you to different kinds of sources that help us reconstruct the social structure. -

Objectives the Main Objective of This Course Is to Introduce Students to Archaeology and the Methods Used by Archaeologists

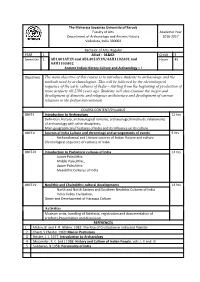

The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Faculty of Arts Academic Year Department of Archaeology and Ancient History 2016-2017 Vadodara, India 390002 Bachelor of Arts: Regular YEAR 1 Allied - 01&02: Credit 3 Semester 1 AB1A01AY1N and AB1A02AY1N/AAH1102A01 and Hours 45 AAH1103A02 Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology – I Objectives The main objective of this course is to introduce students to archaeology and the methods used by archaeologists. This will be followed by the chronological sequence of the early cultures of India – starting from the beginning of production of stone artifacts till 2700 years ago. Students will also examine the origin and development of domestic and religious architecture and development of various religions in the Indian subcontinent COURSE CONTENT/SYLLABUS UNIT-I Introduction to Archaeology 12 hrs Definition, history, archaeological remains, archaeological methods, relationship of archaeology with other disciplines; Main geographical of features of India and its influence on its culture UNIT-II Sources of India Culture and chronology and arrangements of events 5 hrs Archaeological and Literary sources of Indian History and culture Chronological sequence of cultures of India UNIT-III Introduction to Prehistoric cultures of India 14 hrs Lower Paleolithic, Middle Paleolithic, Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic Cultures of India UNIT-IV Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultural developments 14 hrs North and North Eastern and Southern Neolithic Cultures of India Indus Valley Civilization, Origin and Development of Harappa Culture Activities Museum visits, handling of Artefacts, registration and documentation of artefacts,Presentation and discussion REFERENCES 1 Allchin, B. and F. R. Allchin. 1982. The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. -

Autochthonous Aryans? the Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts

Michael Witzel Harvard University Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts. INTRODUCTION §1. Terminology § 2. Texts § 3. Dates §4. Indo-Aryans in the RV §5. Irano-Aryans in the Avesta §6. The Indo-Iranians §7. An ''Aryan'' Race? §8. Immigration §9. Remembrance of immigration §10. Linguistic and cultural acculturation THE AUTOCHTHONOUS ARYAN THEORY § 11. The ''Aryan Invasion'' and the "Out of India" theories LANGUAGE §12. Vedic, Iranian and Indo-European §13. Absence of Indian influences in Indo-Iranian §14. Date of Indo-Aryan innovations §15. Absence of retroflexes in Iranian §16. Absence of 'Indian' words in Iranian §17. Indo-European words in Indo-Iranian; Indo-European archaisms vs. Indian innovations §18. Absence of Indian influence in Mitanni Indo-Aryan Summary: Linguistics CHRONOLOGY §19. Lack of agreement of the autochthonous theory with the historical evidence: dating of kings and teachers ARCHAEOLOGY __________________________________________ Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7-3 (EJVS) 2001(1-115) Autochthonous Aryans? 2 §20. Archaeology and texts §21. RV and the Indus civilization: horses and chariots §22. Absence of towns in the RV §23. Absence of wheat and rice in the RV §24. RV class society and the Indus civilization §25. The Sarasvatī and dating of the RV and the Bråhmaas §26. Harappan fire rituals? §27. Cultural continuity: pottery and the Indus script VEDIC TEXTS AND SCIENCE §28. The ''astronomical code of the RV'' §29. Astronomy: the equinoxes in ŚB §30. Astronomy: Jyotia Vedåga and the -

HISTORY ANCIENT INDIA Thought of the Day

Todays Topic HISTORY ANCIENT INDIA Thought of the Day Everything is Fair in Love & War Todays Topic 16 Mahajanpadas Part – 2 16 MAHAJANPADAS Mahajanapadas with some Vital Informations – 1) Kashi - Capital - Varanasi Location - Varanasi dist of Uttar Pradesh Information - It was one of the most powerful Mahajanapadas. Famous for Cotton Textiles and market for horses. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 2) Koshala / Ayodhya - Capital – Shravasti Location - Faizabad, Gonda region or Eastern UP Information - Most popular king was Prasenjit. He was contemporary and friend of Buddha . 16 MAHAJANPADAS 3) Anga - Capital – Champa / Champanagari Location - Munger and Bhagalpur Dist of Bihar Information - It was a great centre of trade and commerce . In middle of 6th century BC, Anga was annexed by Magadha under Bimbisara. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 4) Vajji ( North Bihar ) - Capital – Vaishali Location – Vaishali dist. of Bihar Information - Vajjis represented a confederacy of eight clans of whom Videhas were the most well known. আটট বংেশর একট সংেঘর িতিনিধ কেরিছেলন, যােদর মেধ িভডাহস সবািধক পিরিচত। • Videhas had their capital at Mithila. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 5) Malla ( Gorakhpur Region ) - Capital – Pavapuri in Kushinagar Location – South of Vaishali dist in UP Information - Buddha died in the vicinity of Kushinagar. Magadha annexed it after Buddha's death. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 6) Chedi - Capital – Suktimati Location – Eastern part of Bundelkhand Information - Chedi territory Corresponds to the Eastern parts of modern Bundelkhand . A branch of Chedis founded a royal dynasty in the kingdom of Kalinga . 16 MAHAJANPADAS 16 MAHAJANPADAS 7) Vatsa - Capital – Kausambi Location – Dist of Allahabad, Mirzapur of Uttar Pradesh Information - Situated around the region of Allahabad. -

A. the Mauryas the Earliest Dynasty to Claim Western India As a Part of Its Empire Was That of the Mauryaus

CHAPTER II Political Background Buddhism has had a history of over one thousand years in Maharashtra. During this long period of Buddhism, certain politi cal powers have played important role in the spread and prosperity of the religion in Western India. The political powers which are mentioned in the inscriptions will be dealt with one by one in a chronological order. A. The Mauryas The earliest dynasty to claim western India as a part of its empire was that of the Mauryaus. The first clear evidence of their rule over the Bombay and Konkan region comes only during the time of Asoka (c. 274-232) , the last ruler of the dynasty. A fragment of his eighth rock edict was found at sopara which may have been one of his district headquarters. Other than this, no Mauryan inscription has yet been found in the western Indian caves. But it is a well-known fact fro© his other edicts that Asoka was not only a royal patron but himself was a devout Buddhist, so, the religion found a very favourable condition for widening its terri tory. As a result, it got rapidly spread in Western India during Asoka's rule and continued to flourish in the same region for over a thousand years. B. The Satavahanas The Mauryan dynasty was succeeded by the satavahana dynasty in the Deccan. This dynasty is the first Known historical dynasty in Maharashtra. From the time the Satavahanas rose to power we begin to obtain political history, administrative system, the religious. 52 53 social and economic conditions of Maharshtra, its art and archi tecture, literature and coinage. -

Iron Technology and Social Change in Early India (350 B.C.-200 B.C.)

B 2001 NML Jamshedpur 831 007, India; Metallurgy in India: A Retrospective; (ISBN: 81-87053-S6-7); Eds: P. Ramachandra Rao and N.G. Goswami; pp. 134-142. 6 Iron Technology and Social Change in Early India (350 B.C.-200 B.C.) V.K. Thakur Professor of History, Patna University, Patna, India. ABSTRACT The paper encompasses the social changes that have been encountered with the development of iron technology during:350 BC to 200 BC. A greater exploitation of iron mines fulfilled the growing demands for the metals on one side and subsequent technological advancement on the other side. All these have social implication too. Archaelogical evidences also support them. Key words Iron technology, Social change, Ashokan inscription, • Archaclogy. The study of iron in early India, both in its technical and social manifestations, suffers from a serious limitation. Most of the available writings are essentially unidimensional in approach. The society as a prime technological variable gets ignored with the result that social complex is always at the receiving .end, almost as hapless passive formation devoid of any dynamism of its own. Such an under standing of the social role of technology sees techniques as independent of the milieu in which these evolve. This tantamounts to taking a position divorcing the process of the origin and growth of a technology from the contemporaiy .social system, a- line of argument that can lead to funny conclusions. It has to be emphasized, therefore, that the study of technology must keep in mina. the dependent social climate. It is common knowledge that a technological innovation is the product of a social system and, in turn, it becomes viable only when the society gets ready for it. -

Department of Ancient History, Culture and Archaeology University of Allahabad C.B.C.S

Department of Ancient History, Culture and Archaeology University of Allahabad C.B.C.S. ---2016-2016 CBCS Syllabus COURSE STRUCTURE WITH MARKS DISTRIBUTION MONSOON (SPRING ) SEMESTER Course Code Paper/Course M.A.Semester -I Maximum Marks ANC -50 1 Core Paper I: Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture (Political, Social and 60 Marks Economic Institutions) ANC -50 2 Core Paper II : Political History of Ancient India (from 6 th Century B.C. to 60 Marks C. 185 B.C.) ANC -50 3 Core Paper III : Indian Paleography 60 Marks ANC -50 4 Paper IV (a) : Archaeological Theories ( Archaeology Group ) Elective OROROR 60 Marks ANC-505 Paper IV (b): Elements of Indian Archaeology: Prehistory ( Non- Archaeology Group ) Sessional Test/Exam (Semester(Semester----I)I)I)I) Sessional Test/Exam (40 Marks) Exam Schedule Test -1* Third week of September 20 Marks Mid -Semester Exam Third week of October 20 Marks Test -2 * Third week of November 20 Marks *Best of the two test’s marks (Test-1 Or Test-2) will be posted End Semester First /Second Week of December 60 Marks Semester –I: Total Max imum Marks 400 Marks COURSE STRUCTURE WITH MARKS DISTRIBUTION WINTER (AUTUMN ) SEMESTER Course Code Paper/Course M.A.Semester -II Maximum Marks ANC -50 6 Core Paper V : Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture (Religion, Philosophy, 60 Marks Literature and Art) ANC -50 7 Core Paper VI : Political History of Ancient India (from C. 185 B.C. to 319 60 Marks A.D.) ANC -50 8 Core Paper VII : Indian Numismatics 60 Marks ANC -509 Paper VIII (a) : Archaeological Methods and Techniques (Archaeology Group ) Elective OROROR 60 Marks ANC-510 Paper VIII (b): Elements of Indian Archaeology: Protohistory and Historical Archaeology ( Non-Archaeology Group ) Sessional Test/Exam (Semester(Semester----II)II)II)II) Sessional Test/Exam (40 Marks) Exam Schedule Test -1* Third week of January 20 Marks Mid -Semester Exam Last week of February 20 Marks Test -2* Third week of March 20 Marks *Best of the two test’s marks (Test-1 Or Test-2) will be posted End Semester Third week of April 60 Marks Semester –II: Total Maximum Marks 400 Marks 1. -

Indian HISTORY

Indian HISTORY AncientIndia THEEARLYMAN The Palaeolithic Age G The fossils of the early human being have (500000 BC-9000 BC) been found in Africa about 2.6 million G The palaeolithic culture of India years back, but there are no such developed in the pleistocene period evidence in India. So, it appears that India or the Ice Age. was inhabited later than Africa. G It seems that Palaeolithic men G The recent reported artefacts from Bori belonged to the Negrito race. Homo in Maharashtra suggest that the Sapiens first appeared towards the appearance of human beings in India was end of this phase. around 1.4 million years ago. G Palaeolithic men were hunters and G The evolution of the Earth’s crust shows food gatherers. They had no four stages. The fourth stage is divided knowledge of agriculture, fire or into Pleistocene (most recent) and pottery, they used tools of Holocene (present). unpolished, rough stones and lived G Man is said to have appeared on the Earth in cave rock shelters. They are also in the early Pleistocene. called Quartzite men. G The early man in India used tools of stone G This age is divided into three phases roughly dressed by crude clipping. This according to the nature of the stone period is therefore, known as the Stone tools used by the people and change Age, which has been divided into in the climate. ¡ The Palaeolithic orOldStoneAge ¡ EarlyorLower Palaeolithic ¡ TheMesolithicorMiddleStone Age ¡ Middle Palaeolithic ¡ TheNeolithicorNewStoneAge ¡ Upper Palaoelithic Age Tools Climate Sites Early Handaxes,cleavers Humidity decreased Soan Valley (Punjab) and choppers Middle Flakes-blades,points, Further decrease in Valleys of Soan, Narmada and borers and scrapers humidity Tungabhadra rivers Upper Scrapersandburin Warmclimate Cavesandrockshelters of this age have been discovered at Bhimbetka near Bhopal 2 GENERAL KNOWLEDGE~ Indian History The Mesolithic Age G Neolithic men lived in caves and decorated their walls with hunting and (9000BC- 4000BC) dancing scenes. -

![[Ancient History] Syllabus](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5432/ancient-history-syllabus-4155432.webp)

[Ancient History] Syllabus

NEHRU GRAM BHARTI VISHWAVIDYALAYA Kotwa-Jamunipur-Dubawal ALLAHABAD SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE CLASSES (I & II, III & IV Semester) (Revised 2016) DEPARTMENT OF ANCIENT HISTORY, CULTURE & ARCHAEOLOGY (1) COURSE STRUCTURE First –Semester Pap. Content Unit Lec. Credit Mar. No. Paper –I Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture 05 40 04 100 (Political Social an Economic (80+20) Institutions) Paper –II Political History of Ancient India 05 40 04 100 (From : 6th Century B.C. to C. 185 B.C) (80+20) Paper -III Indian Paleography 05 40 04 100 (80+20) Paper-IV Paper IV (a) : Archaeological Theories 05 40 04 100 (Archaeology Group) (80+20) OR Paper IV B : Elements of Indian Archaeology Prehistory (Non-Archaeology Group) Semester -II Paper -I Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture 05 40 04 100 (Political Social an Economic Institutions) (80+20) Paper-II Political History of Ancient Indiaa (From C 05 40 04 100 185 B.C. to 319 A.D.) (80+20) Paper –III Indian Numismatics 05 40 04 100 (80+20) Paper-IV(a) Archaeological Methods and Techniques 05 40 04 100 (Archaeology Group) (80+20) OR Elements of Indian Archaeology Protohistory and Historical Archaeology (Non-Archaeology Group) Viva – voice a All Groups 01 100 marks Total Marks First & II Semester Total Marks 900 (2) COURSE STRUCTURE Third –Semester Pap. Content Unit Lec. Credit Mar. No. Paper –I Political History of Ancient India (From 05 40 04 100 AD 319 to 550 A.D.) (80+20) Paper –II Historiography and theories of History 05 40 04 100 (80+20) Paper –III (a) Pre-History : Paleolithic Cultures (With 05 40 04 100