Chronology of Vidarbha Megalithic Culture: an Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(EC) (14.03.2018) Accorded for Expansion of Gondegaon Extension OC, Nagpur Area, Dt

Compliance Report for Amendment in Environmental Clearance (EC) (14.03.2018) Accorded for Expansion of Gondegaon Extension OC, Nagpur Area, Dt. Nagpur Maharashtra. June 2018 Western Coalfields Limited Nagpur 1 Expansion of Gondegaon Extension OC Sub:- Extension in validity of EC accorded for Expansion of Gondegaon Extension OC Coal mine Project from 2.5 MTPA to 3.5 MTPA of Western Coalfields Limited within existing ML area of 917 Ha located in Gondegaon Village, Parseoni Tehsil, Nagpur District, Maharashtra under Clause 7(ii) of the EIA Notification, 2006 – Amendment reg. Ref:- 1. EC letter accorded by MoEF & CC vide letter no. J-11015/106/2009 - IA.II(M) dated 14-03-2018. 1.0 Background: The proposal for Expansion of Gondegaon Extension OC Coal mine Project from 2.5 MTPA to 3.5 MTPA by M/s. Western Coalfields Limited in an area of 917 ha located in village Gondegaon, Tehsil Parseoni, District Nagpur was submitted through online portal of MoEF & CC vide no. IA/MH/CMIN/71601/2017 dated 14-12-2017. Subsequently, the proposal was considered by the EAC (TP & C) in its 24th meeting held on 11-01-2018. Based on the recommendation of the EAC, MoEF & CC accorded EC for the subject project vide letter J-11015/106/2009-IA.II(M) dated 14-03-2018 for enhancement in production capacity from 2.5 MTPA to 3.5 MTPA in a total area of 917 ha (mine lease area 845.74 ha) for a period of one year subject to compliance of terms and conditions and environmental safeguards mentioned below: i. -

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No

District Taluka Center Name Contact Person Address Phone No Mobile No Mhosba Gate , Karjat Tal Karjat Dist AHMEDNAGAR KARJAT Vijay Computer Education Satish Sapkal 9421557122 9421557122 Ahmednagar 7285, URBAN BANK ROAD, AHMEDNAGAR NAGAR Anukul Computers Sunita Londhe 0241-2341070 9970415929 AHMEDNAGAR 414 001. Satyam Computer Behind Idea Offcie Miri AHMEDNAGAR SHEVGAON Satyam Computers Sandeep Jadhav 9881081075 9270967055 Road (College Road) Shevgaon Behind Khedkar Hospital, Pathardi AHMEDNAGAR PATHARDI Dot com computers Kishor Karad 02428-221101 9850351356 Pincode 414102 Gayatri computer OPP.SBI ,PARNER-SUPA ROAD,AT/POST- 02488-221177 AHMEDNAGAR PARNER Indrajit Deshmukh 9404042045 institute PARNER,TAL-PARNER, DIST-AHMEDNAGR /221277/9922007702 Shop no.8, Orange corner, college road AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Dhananjay computer Swapnil Waghchaure Sangamner, Dist- 02425-220704 9850528920 Ahmednagar. Pin- 422605 Near S.T. Stand,4,First Floor Nagarpalika Shopping Center,New Nagar Road, 02425-226981/82 AHMEDNAGAR SANGAMNER Shubham Computers Yogesh Bhagwat 9822069547 Sangamner, Tal. Sangamner, Dist /7588025925 Ahmednagar Opposite OLD Nagarpalika AHMEDNAGAR KOPARGAON Cybernet Systems Shrikant Joshi 02423-222366 / 223566 9763715766 Building,Kopargaon – 423601 Near Bus Stand, Behind Hotel Prashant, AHMEDNAGAR AKOLE Media Infotech Sudhir Fargade 02424-222200 7387112323 Akole, Tal Akole Dist Ahmadnagar K V Road ,Near Anupam photo studio W 02422-226933 / AHMEDNAGAR SHRIRAMPUR Manik Computers Sachin SONI 9763715750 NO 6 ,Shrirampur 9850031828 HI-TECH Computer -

5. from Janapadas to Empire

MODULE - 1 Ancient India 5 Notes FROM JANAPADAS TO EMPIRE In the last chapter we studied how later Vedic people started agriculture in the Ganga basin and settled down in permanent villages. In this chapter, we will discuss how increased agricultural activity and settled life led to the rise of sixteen Mahajanapadas (large territorial states) in north India in sixth century BC. We will also examine the factors, which enabled Magadh one of these states to defeat all others to rise to the status of an empire later under the Mauryas. The Mauryan period was one of great economic and cultural progress. However, the Mauryan Empire collapsed within fifty years of the death of Ashoka. We will analyse the factors responsible for this decline. This period (6th century BC) is also known for the rise of many new religions like Buddhism and Jainism. We will be looking at the factors responsible for the emer- gence of these religions and also inform you about their main doctrines. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson, you will be able to explain the material and social factors (e.g. growth of agriculture and new social classes), which became the basis for the rise of Mahajanapada and the new religions in the sixth century BC; analyse the doctrine, patronage, spread and impact of Buddhism and Jainism; trace the growth of Indian polity from smaller states to empires and list the six- teen Mahajanapadas; examine the role of Ashoka in the consolidation of the empire through his policy of Dhamma; recognise the main features– administration, economy, society and art under the Mauryas and Identify the causes of the decline of the Mauryan empire. -

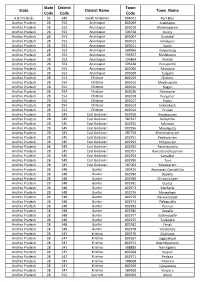

State State Code District Code District Name Town Code Town Name

State District Town State District Name Town Name Code Code Code A & N Islands 35 640 South Andaman 804041 Port Blair Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 803009 Anantapur Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 803010 Dharmavaram Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 594760 Gooty Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 803007 Guntakal Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 803012 Hindupur Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 803011 Kadiri Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 594956 Kalyandurg Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 595357 Madakasira Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 594864 Pamidi Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 595448 Puttaparthi Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 803006 Rayadurg Andhra Pradesh 28 553 Anantapur 803008 Tadpatri Andhra Pradesh 28 554 Chittoor 803019 Chittoor Andhra Pradesh 28 554 Chittoor 803015 Madanapalle Andhra Pradesh 28 554 Chittoor 803016 Nagari Andhra Pradesh 28 554 Chittoor 803020 Palamaner Andhra Pradesh 28 554 Chittoor 803018 Punganur Andhra Pradesh 28 554 Chittoor 803017 Puttur Andhra Pradesh 28 554 Chittoor 803013 Srikalahasti Andhra Pradesh 28 554 Chittoor 803014 Tirupati Andhra Pradesh 28 545 East Godavari 802958 Amalapuram Andhra Pradesh 28 545 East Godavari 587337 Gollaprolu Andhra Pradesh 28 545 East Godavari 802955 Kakinada Andhra Pradesh 28 545 East Godavari 802956 Mandapeta Andhra Pradesh 28 545 East Godavari 587758 Mummidivaram Andhra Pradesh 28 545 East Godavari 802951 Peddapuram Andhra Pradesh 28 545 East Godavari 802954 Pithapuram Andhra Pradesh 28 545 East Godavari 802952 Rajahmundry Andhra Pradesh 28 545 East Godavari 802957 Ramachandrapuram -

Water Quality Annual Report 2010-11-Nagpur

FOR OFFICE USE ONLY GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA WATER RESOURCES DEPARTMENT HYDROLOGY PROJECT (SW) Executive Engineer, Hydrology Project Division, Nagpur WATER QUALITY LAB LEVEL-II, NAGPUR ANNUAL REPORT YEAR 2010-2011 Executive Engineer Hydrology Project Division, Nagpur 1 PREFACE “Water” is a prime natural resource and is considered as a precious national asset. It is a major constituent of all living beings. Water is available in two basic forms i.e. Surface water and Ground Water. This report includes water quality data in Godavari Basin & Tapi Basin for the period of June 2010 to May 2011 by the agency M/s. Ashwamedh Engineers & Consultants Co. Op. So. Ltd. as awarded a contract towards Operation and Maintenance of Water Quality Lab Level-II, Nagpur for the said period. The data has been interpreted to know the affected locations. It is an event of great pleasure to hand over this precise report on analysis of water samples in WQ Laboratory Level – II at Nagpur which is established in Jal Vidnyan Bhavan. It is also a matter of pride to state that this Laboratory is the first in Hydrology Project (SW) to be accredited with ISO 9001:2008 for implementation of Quality Management System (QMS). This booklet attempts to briefly describe an over view and general conclusion based on the basis of water quality data of water samples collected from selected locations for defined frequencies for the reported period. It is expected that this booklet will provide an idea in brief about Water Quality Lab. Level -II at Nagpur. Our efforts can always be updated through valuable suggestions. -

Component-I (A) – Personal Details

Component-I (A) – Personal details: Component-I (B) – Description of module: Subject Name Indian Culture Paper Name Outlines of Indian History Module Name/Title Mahajanapadas- Rise of Magadha – Nandas – Invasion of Alexander Module Id I C/ OIH/ 08 Pre requisites Early History of India Objectives To study the Political institutions of Ancient India from earliest to 3rd Century BCE. Mahajanapadas , Rise of Magadha under the Haryanka, Sisunaga Dynasties, Nanda Dynasty, Persian Invasions, Alexander’s Invasion of India and its Effects Keywords Janapadas, Magadha, Haryanka, Sisunaga, Nanda, Alexander E-text (Quadrant-I) 1. Sources Political and cultural history of the period from C 600 to 300 BCE is known for the first time by a possibility of comparing evidence from different kinds of literary sources. Buddhist and Jaina texts form an authentic source of the political history of ancient India. The first four books of Sutta pitaka -- the Digha, Majjhima, Samyutta and Anguttara nikayas -- and the entire Vinaya pitaka were composed between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. The Sutta nipata also belongs to this period. The Jaina texts Bhagavati sutra and Parisisthaparvan represent the tradition that can be used as historical source material for this period. The Puranas also provide useful information on dynastic history. A comparison of Buddhist, Puranic and Jaina texts on the details of dynastic history reveals more disagreement. This may be due to the fact that they were compiled at different times. Apart from indigenous literary sources, there are number of Greek and Latin narratives of Alexander’s military achievements. They describe the political situation prevailing in northwest on the eve of Alexander’s invasion. -

Intricacy of Certain Verses of Āryabhatīya and Jain Tradition

Intricacy of Certain Verses of Āryabhat ī ya and Jain Tradition – Identification of Asmaka as Sravanabelgola-Camravattam Jain Country K. Chandra Hari ƒ Abstract The conclusions that got derived from astronomical considerations about the homeland of Ārybhat a viz Camravattam (10N51, 75E45) is shown to receive additional support from the socio-cultural factors related to the Jaina tradition in Kerala and South India. It is shown that the A śmaka referred to by Bh āskara-I is the South Indian Jain settlement around Sravan abelgol a (12N51, 76E29) and Dharmasthala (12N53, 75E23) – place receiving the name A śmaka in Jaina canons because of the great stone monoliths at the place. A number of circumstantial evidences have been adduced in support of the above conclusions: (a) Verse 9 of K ālakriy ā giving the Jaina 12 fold division of Yuga (b) Verse 5 of Da śag ītik ā which speaks of Bharata, the first Universal emperor of Jains who accessed the throne from the Ādin ātha R s abhadeva at the beginning of Apasarpin ī Kaliyuga. Āryabhat a’s rejection of the 4:3:2:1 cycle of Kr t ādi yugas based on the Smr tis provide attestation to the new interpretation attempted of the verse (c) Verse 11 of Gol a referring to Nandana-vana and Meru represents terminology borrowed from Tiloyapan n atti of Jains (d) References to Bramah the primordial deity of Jains in verses 1 of Gan it ā and 49, 50 of Gol a (e) Use of Kali Era having the distinct signature of Aryabhata for the first time in South India with the Aihole inscription of the C ālukya King Pulike śi-II. -

Society and Economy During Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: an Archaeological Perspective

Society and Economy during Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: An Archaeological Perspective Tilok Thakuria1 1. Department of History and Archaeology, North Eastern Hill University, Tura Campus, Meghalaya – 794002, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 31July 2017; Revised: 29September 2017; Accepted: 09November 2017 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 5 (2017): 169‐190 Abstract: The paper aims to analyze the archaeological evidence to understand the social and economic formation during the Early Historic period in Maharashtra. The analysis and discussion offered in the paper are based mainly on archaeological evidences unearthed in excavations. However, historical information were also taken into consideration for verification and understanding of archaeological evidence. Keywords: Early History, Megalithic, Pre‐Mauryan, Satavahana, Society, Economy, Maharashtra Introduction History and archaeology need to grow together, instead of parallel, by sharing and utilizing sources as the primary aim of both is to write history. According to Thapar (1984: 193‐194) “The study of social history, economic history and the role of technology in Indian history, being comparatively new to the concern of both archaeologist and historians, require appropriate emphasis. Furthermore, in these fields, the evidence from archaeology can be used more directly. The historian has data on these aspects from literary sources but the data tends to be impressionistic and confined by the context. Archaeology can provide the historian with more precise data on the fundamentals of these aspects of history, resulting thereby in a better comprehension of the early forms of socio‐economic institutions”. The social and economic conditions of Maharashtra during the early historic period have been reconstructed mostly based on available sources like inscriptions, coins and travelers’ accounts. -

HISTORY ANCIENT INDIA Thought of the Day

Todays Topic HISTORY ANCIENT INDIA Thought of the Day Everything is Fair in Love & War Todays Topic 16 Mahajanpadas Part – 2 16 MAHAJANPADAS Mahajanapadas with some Vital Informations – 1) Kashi - Capital - Varanasi Location - Varanasi dist of Uttar Pradesh Information - It was one of the most powerful Mahajanapadas. Famous for Cotton Textiles and market for horses. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 2) Koshala / Ayodhya - Capital – Shravasti Location - Faizabad, Gonda region or Eastern UP Information - Most popular king was Prasenjit. He was contemporary and friend of Buddha . 16 MAHAJANPADAS 3) Anga - Capital – Champa / Champanagari Location - Munger and Bhagalpur Dist of Bihar Information - It was a great centre of trade and commerce . In middle of 6th century BC, Anga was annexed by Magadha under Bimbisara. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 4) Vajji ( North Bihar ) - Capital – Vaishali Location – Vaishali dist. of Bihar Information - Vajjis represented a confederacy of eight clans of whom Videhas were the most well known. আটট বংেশর একট সংেঘর িতিনিধ কেরিছেলন, যােদর মেধ িভডাহস সবািধক পিরিচত। • Videhas had their capital at Mithila. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 5) Malla ( Gorakhpur Region ) - Capital – Pavapuri in Kushinagar Location – South of Vaishali dist in UP Information - Buddha died in the vicinity of Kushinagar. Magadha annexed it after Buddha's death. 16 MAHAJANPADAS 6) Chedi - Capital – Suktimati Location – Eastern part of Bundelkhand Information - Chedi territory Corresponds to the Eastern parts of modern Bundelkhand . A branch of Chedis founded a royal dynasty in the kingdom of Kalinga . 16 MAHAJANPADAS 16 MAHAJANPADAS 7) Vatsa - Capital – Kausambi Location – Dist of Allahabad, Mirzapur of Uttar Pradesh Information - Situated around the region of Allahabad. -

Nagpur District Aaple Sarkar Seva Kendra Sr

Nagpur District Aaple Sarkar Seva Kendra Sr. No District Taluka VLE Name Location Contact No 1 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN KAPIL KHOBRAGADE INDORA CHOWK 8149879645 2 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN RAHUL RAJKOTIYA HASANBAG 9372560201 3 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN NAMITA CHARDE BHANDE PLOT 9326902122 4 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN HARISHCHANDRA BADWAIK MANISH NAGAR 9850227795 5 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN KULDEEP GIRDE RAMESHWARI 9579999323 6 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN BHUPENDRA MENDEKAR PARDI 9175961066 7 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN MOHD IBRAHIM DHAMMADEEP NAGAR 9326823260 8 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN MEENAKSHI PARATE BHANKHEDA 9373658561 9 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN BHUPESH NAGARE GADDGODAM 9325910202 10 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN RUPESH MATE DIGHORI 9175749051 11 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN REENA TANESH FANDE DARSHAN COLONY 9822467937 12 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN ASHA DAHARE HANUMAN NAGAR 9372407585 13 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN ARVIND MAHAMALLA DITPI SIGNAL 9373895346 14 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN GOVINDA POUNIKAR BASTARWARI 9371430824 15 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN SACHIN SAWARKAR CONGRESS NAGAR 9921439262 16 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN YASH CHOPADE MEDICAL CHOWK 8055203555 17 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN SAMYAK KALE ITWARI 9595294456 18 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN VARSHA SANJIV AMBADE VINOBA BHAVE NAGAR 9823154542 19 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN SITARAM BANDHURAM SAHU OM NAGAR BHARATWADA RAOD 7276063142 20 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN NIKHIL KAMDE LADY TALAB 9372469009 21 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN MADHUKAR M. PATIL RAMBAGH 8180093401 8806772227 / 22 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN RAHUL WASNIK UPPALWADI 9423412227 23 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN VANDANA MOTHGHARE VAISHALI NAGAR 9850433703 24 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN RAHUL CHICKHEDE ISHWAR NAGAR 7798277945 25 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN ARCHANA CHANDRSHIKAR PRAJAPATI RANI DURGAWATI CHOWK 8956132909 26 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN PRADIP KUBADE TIMAKI 9860208944 27 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN BINDU RAMESH KAWALE HIWARI NAGAR 9822576847 28 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN VILAS PREMDAS NITNAWARE KAWARPETH 8485070885 29 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN PANKAJ KESHARWANI LALGANJ ZADE CHOWK 9405143249 30 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN ABDUL KALEEM SHEIKH BHALDARPURA,GANDHIBAGH 9326040584 31 Nagpur NAGPUR URBAN SAURABH BHUPENDRA FATE ZINGABAI TAKLI. -

A. the Mauryas the Earliest Dynasty to Claim Western India As a Part of Its Empire Was That of the Mauryaus

CHAPTER II Political Background Buddhism has had a history of over one thousand years in Maharashtra. During this long period of Buddhism, certain politi cal powers have played important role in the spread and prosperity of the religion in Western India. The political powers which are mentioned in the inscriptions will be dealt with one by one in a chronological order. A. The Mauryas The earliest dynasty to claim western India as a part of its empire was that of the Mauryaus. The first clear evidence of their rule over the Bombay and Konkan region comes only during the time of Asoka (c. 274-232) , the last ruler of the dynasty. A fragment of his eighth rock edict was found at sopara which may have been one of his district headquarters. Other than this, no Mauryan inscription has yet been found in the western Indian caves. But it is a well-known fact fro© his other edicts that Asoka was not only a royal patron but himself was a devout Buddhist, so, the religion found a very favourable condition for widening its terri tory. As a result, it got rapidly spread in Western India during Asoka's rule and continued to flourish in the same region for over a thousand years. B. The Satavahanas The Mauryan dynasty was succeeded by the satavahana dynasty in the Deccan. This dynasty is the first Known historical dynasty in Maharashtra. From the time the Satavahanas rose to power we begin to obtain political history, administrative system, the religious. 52 53 social and economic conditions of Maharshtra, its art and archi tecture, literature and coinage. -

Kamptee Coalfield in 2019 with Respect to Area Covered by Social Forestry of 35.04 Sq Km Area (2.61%) in the Year 2016

REPORT ON LAND USE/VEGETATION COVER MAPPING OF KAMPTEE COALFIELD BASED ON SATELLITE DATA FOR THE YEAR 2019 Kanhan River Pench River KAMPTEE COALFIELD Gondegaon OCP Koradi Kamptee OCP Submitted to WESTERN COALFIELD LIMITED NAGPUR,MAHARASTRA . CMPDI Land Use/Vegetation Cover Mapping of Kamptee Coalfield based on Satellite Data for the Year- 2019 February-2020 Remote Sensing Cell Geomatics Division CMPDI, Ranchi Job No 561410027 Page i . CMPDI Document Control Sheet (1) Job No. RSC/561410027 (2) Publication Date February 2020 (3) Number of Pages 37 (4) Number of Figures 8 (5) Number of Tables 10 (6) Number of Plates 2 (7) Title of Report Vegetation cover mapping of Kamptee Coalfield based on satellite data of the year 2019. (8) Aim of the Report To prepare Land use / Vegetation cover map of Kamptee Coalfield on 1:50000 scale for assessing the impact of coal mining on land environment. (9) Executing Unit Remote Sensing Cell, Geomatics Division Central Mine Planning & Design Institute Limited, Gondwana Place, Kanke Road, Ranchi 834008 (10) User Agency Coal India Ltd. (CIL) / Western Coalfield Ltd (WCL). (11) Authors B.K. Choudhary , Chief. Manager (Remote Sensing cell) (12) Security Restriction Restricted Circulation (13) No. of Copies 5 (14) Distribution Statement Official Job No 561410027 Page ii . CMPDI Contents Page No. Document Control Sheet ii List of Figures iv List of Tables iv List of Plates iv 1.0 Introduction 1 - 3 1.1 Project Reference and background 1.2 Objectives 1.3 Location and Accessibility 1.4 Topography & Drainage 2.0 Remote