Iron Technology and Social Change in Early India (350 B.C.-200 B.C.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unit 1 Reconstructing Ancient Society with Special

Harappan Civilisation and UNIT 1 RECONSTRUCTING ANCIENT Other Chalcolithic SOCIETY WITH SPECIAL Cultures REFERENCE TO SOURCES Structure 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Sources 1.1.1 Epigraphy 1.1.2 Numismatics 1.1.3 Archaeology 1.1.4 Literature 1.2 Interpretation 1.3 The Ancient Society: Anthropological Readings 1.4 Nature of Archaeology 1.5 Textual Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Glossary 1.8 Exercises 1.0 INTRODUCTION The primary objective of this unit is to acquaint the learner with the interpretations of the sources that reveal the nature of the ancient society. We therefore need to define the meaning of the term ‘ancient society’ to begin with and then move on to define a loose chronology in the context of the sources and their readings. It would also be useful to have an understanding about the various readings of the sources, a kind of a historiography of the interpretative regime. In order to facilitate a better understanding this unit is divided into five sections. In the introduction we have discussed the range of interpretations that are deployed on the sources and often the sources also become interpretative in nature. The complexity of the sources has also been dealt with in the same context. The new section then discusses the ancient society and what it means. This discussion is spread across the regions and the varying sources that range from archaeology to oral traditions. The last section then gives some concluding remarks. 1.1 SOURCES Here we introduce you to different kinds of sources that help us reconstruct the social structure. -

Society and Economy During Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: an Archaeological Perspective

Society and Economy during Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: An Archaeological Perspective Tilok Thakuria1 1. Department of History and Archaeology, North Eastern Hill University, Tura Campus, Meghalaya – 794002, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 31July 2017; Revised: 29September 2017; Accepted: 09November 2017 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 5 (2017): 169‐190 Abstract: The paper aims to analyze the archaeological evidence to understand the social and economic formation during the Early Historic period in Maharashtra. The analysis and discussion offered in the paper are based mainly on archaeological evidences unearthed in excavations. However, historical information were also taken into consideration for verification and understanding of archaeological evidence. Keywords: Early History, Megalithic, Pre‐Mauryan, Satavahana, Society, Economy, Maharashtra Introduction History and archaeology need to grow together, instead of parallel, by sharing and utilizing sources as the primary aim of both is to write history. According to Thapar (1984: 193‐194) “The study of social history, economic history and the role of technology in Indian history, being comparatively new to the concern of both archaeologist and historians, require appropriate emphasis. Furthermore, in these fields, the evidence from archaeology can be used more directly. The historian has data on these aspects from literary sources but the data tends to be impressionistic and confined by the context. Archaeology can provide the historian with more precise data on the fundamentals of these aspects of history, resulting thereby in a better comprehension of the early forms of socio‐economic institutions”. The social and economic conditions of Maharashtra during the early historic period have been reconstructed mostly based on available sources like inscriptions, coins and travelers’ accounts. -

Objectives the Main Objective of This Course Is to Introduce Students to Archaeology and the Methods Used by Archaeologists

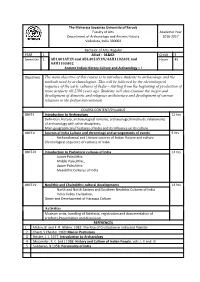

The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Faculty of Arts Academic Year Department of Archaeology and Ancient History 2016-2017 Vadodara, India 390002 Bachelor of Arts: Regular YEAR 1 Allied - 01&02: Credit 3 Semester 1 AB1A01AY1N and AB1A02AY1N/AAH1102A01 and Hours 45 AAH1103A02 Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology – I Objectives The main objective of this course is to introduce students to archaeology and the methods used by archaeologists. This will be followed by the chronological sequence of the early cultures of India – starting from the beginning of production of stone artifacts till 2700 years ago. Students will also examine the origin and development of domestic and religious architecture and development of various religions in the Indian subcontinent COURSE CONTENT/SYLLABUS UNIT-I Introduction to Archaeology 12 hrs Definition, history, archaeological remains, archaeological methods, relationship of archaeology with other disciplines; Main geographical of features of India and its influence on its culture UNIT-II Sources of India Culture and chronology and arrangements of events 5 hrs Archaeological and Literary sources of Indian History and culture Chronological sequence of cultures of India UNIT-III Introduction to Prehistoric cultures of India 14 hrs Lower Paleolithic, Middle Paleolithic, Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic Cultures of India UNIT-IV Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultural developments 14 hrs North and North Eastern and Southern Neolithic Cultures of India Indus Valley Civilization, Origin and Development of Harappa Culture Activities Museum visits, handling of Artefacts, registration and documentation of artefacts,Presentation and discussion REFERENCES 1 Allchin, B. and F. R. Allchin. 1982. The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. -

Autochthonous Aryans? the Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts

Michael Witzel Harvard University Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts. INTRODUCTION §1. Terminology § 2. Texts § 3. Dates §4. Indo-Aryans in the RV §5. Irano-Aryans in the Avesta §6. The Indo-Iranians §7. An ''Aryan'' Race? §8. Immigration §9. Remembrance of immigration §10. Linguistic and cultural acculturation THE AUTOCHTHONOUS ARYAN THEORY § 11. The ''Aryan Invasion'' and the "Out of India" theories LANGUAGE §12. Vedic, Iranian and Indo-European §13. Absence of Indian influences in Indo-Iranian §14. Date of Indo-Aryan innovations §15. Absence of retroflexes in Iranian §16. Absence of 'Indian' words in Iranian §17. Indo-European words in Indo-Iranian; Indo-European archaisms vs. Indian innovations §18. Absence of Indian influence in Mitanni Indo-Aryan Summary: Linguistics CHRONOLOGY §19. Lack of agreement of the autochthonous theory with the historical evidence: dating of kings and teachers ARCHAEOLOGY __________________________________________ Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7-3 (EJVS) 2001(1-115) Autochthonous Aryans? 2 §20. Archaeology and texts §21. RV and the Indus civilization: horses and chariots §22. Absence of towns in the RV §23. Absence of wheat and rice in the RV §24. RV class society and the Indus civilization §25. The Sarasvatī and dating of the RV and the Bråhmaas §26. Harappan fire rituals? §27. Cultural continuity: pottery and the Indus script VEDIC TEXTS AND SCIENCE §28. The ''astronomical code of the RV'' §29. Astronomy: the equinoxes in ŚB §30. Astronomy: Jyotia Vedåga and the -

Department of Ancient History, Culture and Archaeology University of Allahabad C.B.C.S

Department of Ancient History, Culture and Archaeology University of Allahabad C.B.C.S. ---2016-2016 CBCS Syllabus COURSE STRUCTURE WITH MARKS DISTRIBUTION MONSOON (SPRING ) SEMESTER Course Code Paper/Course M.A.Semester -I Maximum Marks ANC -50 1 Core Paper I: Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture (Political, Social and 60 Marks Economic Institutions) ANC -50 2 Core Paper II : Political History of Ancient India (from 6 th Century B.C. to 60 Marks C. 185 B.C.) ANC -50 3 Core Paper III : Indian Paleography 60 Marks ANC -50 4 Paper IV (a) : Archaeological Theories ( Archaeology Group ) Elective OROROR 60 Marks ANC-505 Paper IV (b): Elements of Indian Archaeology: Prehistory ( Non- Archaeology Group ) Sessional Test/Exam (Semester(Semester----I)I)I)I) Sessional Test/Exam (40 Marks) Exam Schedule Test -1* Third week of September 20 Marks Mid -Semester Exam Third week of October 20 Marks Test -2 * Third week of November 20 Marks *Best of the two test’s marks (Test-1 Or Test-2) will be posted End Semester First /Second Week of December 60 Marks Semester –I: Total Max imum Marks 400 Marks COURSE STRUCTURE WITH MARKS DISTRIBUTION WINTER (AUTUMN ) SEMESTER Course Code Paper/Course M.A.Semester -II Maximum Marks ANC -50 6 Core Paper V : Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture (Religion, Philosophy, 60 Marks Literature and Art) ANC -50 7 Core Paper VI : Political History of Ancient India (from C. 185 B.C. to 319 60 Marks A.D.) ANC -50 8 Core Paper VII : Indian Numismatics 60 Marks ANC -509 Paper VIII (a) : Archaeological Methods and Techniques (Archaeology Group ) Elective OROROR 60 Marks ANC-510 Paper VIII (b): Elements of Indian Archaeology: Protohistory and Historical Archaeology ( Non-Archaeology Group ) Sessional Test/Exam (Semester(Semester----II)II)II)II) Sessional Test/Exam (40 Marks) Exam Schedule Test -1* Third week of January 20 Marks Mid -Semester Exam Last week of February 20 Marks Test -2* Third week of March 20 Marks *Best of the two test’s marks (Test-1 Or Test-2) will be posted End Semester Third week of April 60 Marks Semester –II: Total Maximum Marks 400 Marks 1. -

![[Ancient History] Syllabus](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5432/ancient-history-syllabus-4155432.webp)

[Ancient History] Syllabus

NEHRU GRAM BHARTI VISHWAVIDYALAYA Kotwa-Jamunipur-Dubawal ALLAHABAD SYLLABUS FOR POST GRADUATE CLASSES (I & II, III & IV Semester) (Revised 2016) DEPARTMENT OF ANCIENT HISTORY, CULTURE & ARCHAEOLOGY (1) COURSE STRUCTURE First –Semester Pap. Content Unit Lec. Credit Mar. No. Paper –I Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture 05 40 04 100 (Political Social an Economic (80+20) Institutions) Paper –II Political History of Ancient India 05 40 04 100 (From : 6th Century B.C. to C. 185 B.C) (80+20) Paper -III Indian Paleography 05 40 04 100 (80+20) Paper-IV Paper IV (a) : Archaeological Theories 05 40 04 100 (Archaeology Group) (80+20) OR Paper IV B : Elements of Indian Archaeology Prehistory (Non-Archaeology Group) Semester -II Paper -I Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture 05 40 04 100 (Political Social an Economic Institutions) (80+20) Paper-II Political History of Ancient Indiaa (From C 05 40 04 100 185 B.C. to 319 A.D.) (80+20) Paper –III Indian Numismatics 05 40 04 100 (80+20) Paper-IV(a) Archaeological Methods and Techniques 05 40 04 100 (Archaeology Group) (80+20) OR Elements of Indian Archaeology Protohistory and Historical Archaeology (Non-Archaeology Group) Viva – voice a All Groups 01 100 marks Total Marks First & II Semester Total Marks 900 (2) COURSE STRUCTURE Third –Semester Pap. Content Unit Lec. Credit Mar. No. Paper –I Political History of Ancient India (From 05 40 04 100 AD 319 to 550 A.D.) (80+20) Paper –II Historiography and theories of History 05 40 04 100 (80+20) Paper –III (a) Pre-History : Paleolithic Cultures (With 05 40 04 100 -

The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline

The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline D. D. Kosambi Preface 1. THE HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 1.1. The Indian Scene 1.2. The Modern Ruling Class 1.3. The Difficulties Facing the Historian 1.4. The Need to Study Rural and Tribal Society 1.5. The Villages 1.6. Recapitulation 2. PRIMITIVE LIFE AND PREHISTORY 2.1. The Golden Age 2.2. Prehistory and Primitive Life 2.3. Prehistoric Man in India 2.4. Primitive Survivals in the Means of Production 2.5. Primitive Survivals in the Superstructure 3. THE FIRST CITIES 3.1. The Discovery of the Indus Culture 3.2. Production in the Indus Culture 3.3. Special Features of the Indus Civilisation 3.4. The Social Structure 4. THE ARYANS 4.1. The Aryan Peoples 4.2. The Aryan Way of Life 4.3. Eastward Progress 4.4. Aryans after the Rigveda 4.5. The Urban Revival 4.6. The Epic Period 5. FROM TRIBE TO SOCIETY 5.1. The New Religions 5.2. The Middle Way 5.3. The Buddha and His Society 5.4. The Dark Hero of the Yadus 5.5. Kosala and Magadha 6. STATE AND RELIGION IN GREATER MAGADHA 6.1. Completion of the Magadhan Conquest 6.2. Magadhan Statecraft 6.3. Administration of the Land 6.4. The State and Commodity Production 6.5. Asoka and the Culmination of the Magadhan Empire 7. TOWARDS FEUDALISM 7.1. The New Priesthood 7.2. The Evolution of Buddhism 7.3. Political and Economic Changes 7.4. Sanskrit Literature and Drama Preface IT is doubtless more important to change history than to write it, just as it would be better to do something about the weather rather than merely talk about it. -

MATERIAL LIFE of NORTHERN INDIA C. 600 B.C-320 B.C

MATERIAL LIFE OF NORTHERN INDIA c. 600 B.C-320 B.C. ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF IN HISTORY By MOHAMMAD NAZRUL BARI Under the Supervision of MR. EHTESHAMUL HODA CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2004 ABSTRACT The thesis entitled "Material life of Northern India, c 600-320 B C", is an attempt to make a micro study mainly because it is comparatively rich in materials available, both in archaeology and literature. Dymond, a proponent of full co-ordination, says "We have a moral duty to find out as much of truth as possible and should therefore be prepared to use whatever evidence survives If it is of different kinds, we must see it in all of its variety to co-ordinate it " From the geographical point of view, as well, the region of northern India had been the hub of political, economic and cultural activities Archaeological materials from the excavations in the northern India had been taken into account by earlier scholars, such as Vibha Tripathi, T.N., Roy and others, but such earlier attempts had their own drawbacks, particularly in two respects. First, earlier works generally present an overview in relation to time and space Secondly, since the time of earlier works more materials have come to light. Though literature, relevant to the period has been exploited to bring out the life and conditions of the people with the occasional support from archaeological finds, but complete synthesis is still a need. The microscopic study undertaken in this research is to have a better understanding of the material life of the people in its various facets. -

Ancient India the Prehistoric Period

Ancient India The Prehistoric Period The prehistoric period in the history of mankind can roughly be dated from 200000 BC to about 3500-2500 BC, when the first civilisations began to take shape. The history of India is no exception. The first modern human beings or the Homo sapiens set foot on the Indian subcontinent anywhere between 200000 BC and 40000 BC and they soon spread throughout a large part of the subcontinent, including peninsular India. They continuously flooded the Indian subcontinent in waves after waves of migration from what is present-day Iran. These primitive people moved in groups of few ‘families’ and lived mainly on hunting and gathering. Stone Age The age when the prehistoric man began to use stones for utilitarian purpose is termed as the Stone Age. The Stone Age is divided into three broad divisions — Paleolithic Age or the Old Stone Age (from unknown till 8000 BC), Mesolithic Age or the Middle Stone Age (8000 BC-4000 BC) and the Neolithic Age or the New Stone Age (4000 BC-2500 BC) on the basis of the specialization of the stone tools, which were made during that time. Paleolithic Age The human beings living in the Paleolithic Age were essentially food gatherers and depended on nature for food. The art of hunting and stalking wild animals individually and later in groups led to these people making stone weapons and tools. First, crudely carved out stones were used in hunting, but as the size of the groups began to increase and there was need for more food, these people began to make “specialized tools” by flaking stones, which were pointed on one end. -

Ancient Iron Making in India

Iron & Steel Heritage of India Ed. S. Ronganathan, ATM 97, Jamshedpur, pp. 29-59 ANCIENT IRON MAKING IN INDIA B. PRAKASH Benaras Hindu University, Varanasi —221005 ABSTRACT The discovery of Agni (i.e., fire) has been very closely related with the process of human civilization and it has been worshipped during the Vedic period or even earlier. The havankund has been described as the open air laboratory of the .Vedic people and they had gained ample knowledge about the physics and chemistry offire. The beginning of pyrotechnology could be traced to the Vedic period when man worshipped Agni for blessings of metals like gold, .silver, copper, iron, tin, lead and their alloys. The archaeological evidence has confirmed that iron technology began only during the late second millennium BC and it has been proved to be of indigenous origin. The paper gives a brief review of the ancient Indian community associated with this craft, viz., Agarias and other tribes wor- shipping God `Asura'. They developed their own secret technology of iron smelting to produce iron and steel of excellent quality. Their practice of charcoal iron smelting was considered to have stopped at least for the past one century but recent surveys have traced it to continue to be practiced in some parts of Madhya Pradesh, Eastern U. P. and Bihar. It has provided an opportunity to study this ancient craft, its thermo-chemistry and process control as well as the details of the furnace construction and its operation. The high level of skill in smelting sponge iron blooms and its refining to produce tonnes of iron is certified by the uniformity of composition of the corrosion resistant iron used in the manufacture of some of the heaviest ancient forgings existing in the country. -

Chapter 2 Early Iron Age in India Vis-A-Vis Second Urbanisation

Chapter 2 Early Iron Age in India vis-a-vis Second Urbanisation The present chapter is mainly aimed to draw a broad outline of the Early Iron Age in North and South India. Urbanisation and the formation of State which followed the Early Iron Age is the important point of discussion here. Special emphasis is laid on understanding the process of urbanisation in the Ganga valley since it is well documented. An attempt has been made to comprehend the importance, role and background of Early Iron Age in this process and see how far they can be applied to the area of present study. The Early Iron Age in India marks the period of beginning of iron technology, subsequent production and its widespread cultural use along the subcontinent. Though initially, researchers had ascribed a date of about 7th- 6th cent BC to the emergence of iron in the Indian scenario (Wheeler 1946); now the dates for the same and its harness to the cultural development of the region go back in the early part of the second millennium BC (Tewari 2003). The use of iron led to change in the cultural milieu and also later ushered in the phase of urbanisation in Ganga Valley. This urbanisation which is popularly known as second urbanisation was characterized by coming up of cities and development of states in the Ganga valley and neighbouring regions and gradually in the entire subcontinent. Though as stated above, iron made an early entry, the urban characteristics are seen only around 7th- 6th cent BC. The period is known as NBPW period due to the presence of the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) all over northern India and often found spread to far off regions including Sri Lanka. -

Kauśāmbī: a Cultural Centre of Ancient India

Kauśāmbī: A Cultural Centre of Ancient India Shawttiki Ojha (M.Phil.)Department of Ancient Indian History and Culture University of Calcutta Guest Lecturer (Naba Ballygunje Mahavidyalaya, Kalyani Mahavidyalaya) Abstract Kauśāmbī is an ancient city of Indian Subcontinent which has a historical identity. It was famous as „Kośāmbī‟ or „Vatsapattana‟ in ancient times. It was the capital of „Vatsa‟ Mahājanapada which located at modern Allāhābād on the banks of river Yamunā in the Uttarpradesh State. Now-a-days this region is identified with the village of „Kosām‟ at Allāhābād. Numerous literary and archaeological sources mention about this region. Brāhmaṇya texts, „Aṣṭyādhoyī‟ of Pāṇini, „Mahābhāṣya‟ of Pataňjali, many Buddhist texts, „Rāmāyaṇa‟, „Mahābhārata‟, „Meghdūtam‟ of Kālidāsa, descriptions of Chinese pilgrims Fa-Hien and Hiuen-Tsang, „Vṛhatkathāmaňjarī‟ etc many texts clearly depict the various aspects of Kauśāmbī. This city was ruled by famous king Udayana. His political power and love for Buddhism made this place famous in ancient India. Nandas, Mauryas, Śuṅga, Kāṇvas, Mitra, Kuṣāṇa, Magha, Vākāṭaka, Gupta and Pratihāras ruled here. Kauśāmbī became a prosperous economic zone for its perfect geographical location. It was connected with Vārāṇasī, Śrāvastī, Ujjayinī, Pāṭaliputra, Vidiśā, Rājgṛha and with many places by trade routes. The merchants and rich people used this place as a mediator zone because this place was connected with many ports, places and Burmā. Kauśāmbī was famous as Buddhist and Jain tīrtha. Gautama Buddha himself came here. Many Buddhist monks i.e. „Mahākācchyāna‟, „Ānanda‟, „Moggoliputta‟ etc resided here. King Udayana and many rich people of Kauśāmbī patronized Buddhism. Ghoṣitārāma, Kukkuṭārāma, Pāvārika-Āmṛvana and Badarikārāma were built by accordingly by Ghoṣita, Kukkuṭa, Pāvāriya and Mauryan king Aśoka.