UNIT 4 MEGALITHIC CULTURES Chalcolithic Cultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neolithic and Earlier Bronze Age Key Sites Southeast Wales – Neolithic

A Research Framework for the Archaeology of Wales Key Sites, Southeast Wales, 22/12/2003 Neolithic and earlier Bronze Age Key Sites Southeast Wales – Neolithic and early Bronze Age 22/12/2003 Neolithic Domestic COED-Y-CWMDDA Enclosure with evidence for flint-working Owen-John 1988 CEFN GLAS (SN932024) Late Neolithic hut floor dated to 4110-70 BP. Late Neolithic flints have been found at this site. Excavated 1973 Unpublished: see Grimes 1984 PEN-Y-BONT, OGMORE (SS863756) Pottery, hearth and flints Hamilton and Aldhouse-Green 1998; 1999; Gibson 1998 MOUNT PLEASANT, NEWTON NOTTAGE (SS83387985) Hut, hearth, pottery Savory 1952; RCAHMW 1976a CEFN CILSANWS HUT SITE (SO02480995) Hut consisting of 46 stake holes found under cairn. The hut contained fragments of Mortlake style Peterborough Ware and flint flakes Webley 1958; RCAHMW 1997 CEFN BRYN 10 (GREAT CARN) SAM Gml96 (SS49029055) Trench, pit, posthole and hearth associated with Peterborough ware and worked flint; found under cairn. Ward 1987 Funerary and ritual CEFN BRYN BURIAL CHAMBER (NICHOLASTON) SAM Gml67 (SS50758881) Partly excavated chambered tomb, with an orthostatic chamber surviving in a roughly central position in what remains of a long mound. The mound was made up peaty soil and stone fragments, and no trace of an entrance passage was found. The chamber had been robbed at some time before the excavation. Williams 1940, 178-81 CEFN DRUM CHAMBERED TOMB (SN61360453,) Discovered during the course of the excavation of a deserted medieval settlement on Cefn Drum. A pear-shaped chamber of coursed rubble construction, with an attached orthostatic passage ending in a pit in the mouth of a hornwork and containing cremated bone and charcoal, were identified within the remains of a mound with some stone kerbing. -

How to Tell a Cromlech from a Quoit ©

How to tell a cromlech from a quoit © As you might have guessed from the title, this article looks at different types of Neolithic or early Bronze Age megaliths and burial mounds, with particular reference to some well-known examples in the UK. It’s also a quick overview of some of the terms used when describing certain types of megaliths, standing stones and tombs. The definitions below serve to illustrate that there is little general agreement over what we could classify as burial mounds. Burial mounds, cairns, tumuli and barrows can all refer to man- made hills of earth or stone, are located globally and may include all types of standing stones. A barrow is a mound of earth that covers a burial. Sometimes, burials were dug into the original ground surface, but some are found placed in the mound itself. The term, barrow, can be used for British burial mounds of any period. However, round barrows can be dated to either the Early Bronze Age or the Saxon period before the conversion to Christianity, whereas long barrows are usually Neolithic in origin. So, what is a megalith? A megalith is a large stone structure or a group of standing stones - the term, megalith means great stone, from two Greek words, megas (meaning: great) and lithos (meaning: stone). However, the general meaning of megaliths includes any structure composed of large stones, which include tombs and circular standing structures. Such structures have been found in Europe, Asia, Africa, Australia, North and South America and may have had religious significance. Megaliths tend to be put into two general categories, ie dolmens or menhirs. -

Stone-Cist Grave at Kaseküla, Western Estonia, in the Light of Ams Dates of the Human Bones

Estonian Journal of Archaeology, 2012, 16, 2, 91–117 doi: 10.3176/arch.2012.2.01 Margot Laneman STONE-CIST GRAVE AT KASEKÜLA, WESTERN ESTONIA, IN THE LIGHT OF AMS DATES OF THE HUMAN BONES The article discusses new AMS dates of the human bones at stone-cist grave I at Kaseküla, western Estonia, in the context of previously existent radiocarbon dates, artefact finds and osteological studies. There are altogether 12 radiocarbon dates for 10 inhumations (i.e. roughly a third of all burials) of the grave, provided by two laboratories. The dates suggest three temporally separated periods in the use life of the grave(s): the Late Bronze Age, the Pre-Roman Iron Age and the Late Iron Age. In the latter period, the grave was probably reserved for infant burials only. Along with chronological issues, the article discusses the apparently unusual structure of the grave and compares two competing osteological studies of the grave’s bone assemblage from an archaeologist’s point of view. Margot Laneman, Institute of History and Archaeology, University of Tartu, 18 Ülikooli St., 50090 Tartu, Estonia; [email protected] Introduction The main aim of this article is to present and discuss new radiocarbon (AMS) dates of the human bones collected from stone-cist grave I at Kaseküla, western Estonia. The stone-cist grave was excavated by Mati Mandel in 1973 with the purpose of specifying the settlement history of the region (Mandel 1975). So far it has remained the only excavated stone-cist grave in mainland western Estonia (Mandel 2003, fig. 20). Excavation also uncovered a Late Neolithic settlement site beneath the grave, which was further investigated by Aivar Kriiska in 1997 (Kriiska et al. -

Megalithic Astronomy in South India

In Nakamura, T., Orchiston, W., Sôma, M., and Strom, R. (eds.), 2011. Mapping the Oriental Sky. Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Oriental Astronomy. Tokyo, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. Pp. xx-xx. MEGALITHIC ASTRONOMY IN SOUTH INDIA Srikumar M. MENON Faculty of Architecture, Manipal Institute of Technology, Manipal – 576104, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected] and Mayank N. VAHIA Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, India, and Manipal Advanced Research Group, Manipal University, Manipal – 576104, Karnataka, India. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The megalithic monuments of peninsular India, believed to have been erected in the Iron Age (1500BC – 200AD), can be broadly categorized into sepulchral and non-sepulchral in purpose. Though a lot of work has gone into the study of these monuments since Babington first reported megaliths in India in 1823, not much is understood about the knowledge systems extant in the period when these were built – in science and engineering, and especially in mathematics and astronomy. We take a brief look at the archaeological understanding of megaliths, before making a detailed assessment of a group of megaliths in the south Canara region of Karnataka State in South India that were hitherto assumed to be haphazard clusters of menhirs. Our surveys have indicated that there is a positive correlation of sight-lines with sunrise and sunset points on the horizon for both summer and winter solstices. We identify five such monuments in the region and present the survey results for one of these sites, demonstrating their astronomical implications. We also discuss the possible use of megaliths in the form of stone alignments/ avenues as calendar devices. -

Unit 1 Reconstructing Ancient Society with Special

Harappan Civilisation and UNIT 1 RECONSTRUCTING ANCIENT Other Chalcolithic SOCIETY WITH SPECIAL Cultures REFERENCE TO SOURCES Structure 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Sources 1.1.1 Epigraphy 1.1.2 Numismatics 1.1.3 Archaeology 1.1.4 Literature 1.2 Interpretation 1.3 The Ancient Society: Anthropological Readings 1.4 Nature of Archaeology 1.5 Textual Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Glossary 1.8 Exercises 1.0 INTRODUCTION The primary objective of this unit is to acquaint the learner with the interpretations of the sources that reveal the nature of the ancient society. We therefore need to define the meaning of the term ‘ancient society’ to begin with and then move on to define a loose chronology in the context of the sources and their readings. It would also be useful to have an understanding about the various readings of the sources, a kind of a historiography of the interpretative regime. In order to facilitate a better understanding this unit is divided into five sections. In the introduction we have discussed the range of interpretations that are deployed on the sources and often the sources also become interpretative in nature. The complexity of the sources has also been dealt with in the same context. The new section then discusses the ancient society and what it means. This discussion is spread across the regions and the varying sources that range from archaeology to oral traditions. The last section then gives some concluding remarks. 1.1 SOURCES Here we introduce you to different kinds of sources that help us reconstruct the social structure. -

Society and Economy During Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: an Archaeological Perspective

Society and Economy during Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: An Archaeological Perspective Tilok Thakuria1 1. Department of History and Archaeology, North Eastern Hill University, Tura Campus, Meghalaya – 794002, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 31July 2017; Revised: 29September 2017; Accepted: 09November 2017 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 5 (2017): 169‐190 Abstract: The paper aims to analyze the archaeological evidence to understand the social and economic formation during the Early Historic period in Maharashtra. The analysis and discussion offered in the paper are based mainly on archaeological evidences unearthed in excavations. However, historical information were also taken into consideration for verification and understanding of archaeological evidence. Keywords: Early History, Megalithic, Pre‐Mauryan, Satavahana, Society, Economy, Maharashtra Introduction History and archaeology need to grow together, instead of parallel, by sharing and utilizing sources as the primary aim of both is to write history. According to Thapar (1984: 193‐194) “The study of social history, economic history and the role of technology in Indian history, being comparatively new to the concern of both archaeologist and historians, require appropriate emphasis. Furthermore, in these fields, the evidence from archaeology can be used more directly. The historian has data on these aspects from literary sources but the data tends to be impressionistic and confined by the context. Archaeology can provide the historian with more precise data on the fundamentals of these aspects of history, resulting thereby in a better comprehension of the early forms of socio‐economic institutions”. The social and economic conditions of Maharashtra during the early historic period have been reconstructed mostly based on available sources like inscriptions, coins and travelers’ accounts. -

Kd Lald`Fr;K¡

Megalithic Cultures c`gn~ik’kkf.kd laLd`fr;k¡ Dr. Anil Kumar Professor Ancient Indian History and Archaeology University of Lucknow [email protected] [email protected] Introduction According to V. Gordon Childe the term ‘Megalith’ is derived from two Greeks words, megas means large and lithos means stone and originally introduced by antiquaries to describe a fairly easily definable class of monuments in western and northern Europe, consisting of huge, undress stones. In other words, the Megaliths usually refer to the burials made of large stones in graveyard away from the habitation area. Meadows Taylor believed that resemblances of the east and west were not merely accidental and that “the actual monuments of celto-scythian tribes are found in India and being examined are found to agree in all respects with those of Europe.” James Fergusson argued that they were all “erected by partially civilized races after they had come in contact with the Romans.’ He also stated that it was difficult to comprehend “how and when intercourse could have taken place which led to their similarity.” People like Dubreuil argued an Aryan origin for the megaliths. Elliot and Perry saw the south Indian megaliths and monumental stone architecture as one of the elements reflecting a manifestation of the Egyptian archaic civilization as far back as 1923. In 1872, Fergusson brought out his excellent work entitled “Rude Stone Monuments in all Countries: their age and uses. This first attracted the attention of scholars. Types of megaliths The megaliths are, indeed, among the most widespread remains of stone both in time and space. -

Objectives the Main Objective of This Course Is to Introduce Students to Archaeology and the Methods Used by Archaeologists

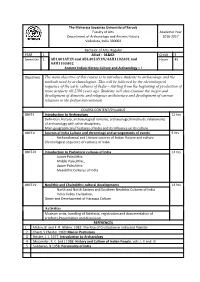

The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Faculty of Arts Academic Year Department of Archaeology and Ancient History 2016-2017 Vadodara, India 390002 Bachelor of Arts: Regular YEAR 1 Allied - 01&02: Credit 3 Semester 1 AB1A01AY1N and AB1A02AY1N/AAH1102A01 and Hours 45 AAH1103A02 Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology – I Objectives The main objective of this course is to introduce students to archaeology and the methods used by archaeologists. This will be followed by the chronological sequence of the early cultures of India – starting from the beginning of production of stone artifacts till 2700 years ago. Students will also examine the origin and development of domestic and religious architecture and development of various religions in the Indian subcontinent COURSE CONTENT/SYLLABUS UNIT-I Introduction to Archaeology 12 hrs Definition, history, archaeological remains, archaeological methods, relationship of archaeology with other disciplines; Main geographical of features of India and its influence on its culture UNIT-II Sources of India Culture and chronology and arrangements of events 5 hrs Archaeological and Literary sources of Indian History and culture Chronological sequence of cultures of India UNIT-III Introduction to Prehistoric cultures of India 14 hrs Lower Paleolithic, Middle Paleolithic, Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic Cultures of India UNIT-IV Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultural developments 14 hrs North and North Eastern and Southern Neolithic Cultures of India Indus Valley Civilization, Origin and Development of Harappa Culture Activities Museum visits, handling of Artefacts, registration and documentation of artefacts,Presentation and discussion REFERENCES 1 Allchin, B. and F. R. Allchin. 1982. The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. -

Autochthonous Aryans? the Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts

Michael Witzel Harvard University Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts. INTRODUCTION §1. Terminology § 2. Texts § 3. Dates §4. Indo-Aryans in the RV §5. Irano-Aryans in the Avesta §6. The Indo-Iranians §7. An ''Aryan'' Race? §8. Immigration §9. Remembrance of immigration §10. Linguistic and cultural acculturation THE AUTOCHTHONOUS ARYAN THEORY § 11. The ''Aryan Invasion'' and the "Out of India" theories LANGUAGE §12. Vedic, Iranian and Indo-European §13. Absence of Indian influences in Indo-Iranian §14. Date of Indo-Aryan innovations §15. Absence of retroflexes in Iranian §16. Absence of 'Indian' words in Iranian §17. Indo-European words in Indo-Iranian; Indo-European archaisms vs. Indian innovations §18. Absence of Indian influence in Mitanni Indo-Aryan Summary: Linguistics CHRONOLOGY §19. Lack of agreement of the autochthonous theory with the historical evidence: dating of kings and teachers ARCHAEOLOGY __________________________________________ Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7-3 (EJVS) 2001(1-115) Autochthonous Aryans? 2 §20. Archaeology and texts §21. RV and the Indus civilization: horses and chariots §22. Absence of towns in the RV §23. Absence of wheat and rice in the RV §24. RV class society and the Indus civilization §25. The Sarasvatī and dating of the RV and the Bråhmaas §26. Harappan fire rituals? §27. Cultural continuity: pottery and the Indus script VEDIC TEXTS AND SCIENCE §28. The ''astronomical code of the RV'' §29. Astronomy: the equinoxes in ŚB §30. Astronomy: Jyotia Vedåga and the -

New Discoveries and Documentation of Megalithic Structes in Juffain Dolmen Archaeological Field, Jordan

Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry, Vol. 18, No 1, (2018), pp. 175-197 Copyright © 2018 MAA Open Access. Printed in Greece. All rights reserved. DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.1161357 NEW DISCOVERIES AND DOCUMENTATION OF MEGALITHIC STRUCTES IN JUFFAIN DOLMEN ARCHAEOLOGICAL FIELD, JORDAN Atef Shiyab1, Kennett Schath, Hussein Al-jarrah, Firas Alawneh2, Wassef Al Sekheneh1 1Faculty of Archaeology and Anthropology-Yarmouk University, Irbid, Jordan. 2Department of Conservation Science, Queen Rania Faculty of Tourism & Heritage, Hashemite University, P.O. Box 330127 Postal Code 13115 Zarqa, Jordan Received: 02/01/2018 Accepted: 02/02/2018 Corresponding Author: Firas Alawneh ([email protected]) ABSTRACT The research presented here is about documentation, analysis and sharing new discoveries of Juffain mega- lithic field. Using Geographic information system (GIS) to produce topographical maps is the basis for the conservation and the development of a Dolmen Heritage Park. A previous survey with Perugia University, was performed in 2016, which provide insight about the high density of megalithic structures and study of structure distribution. While collecting data for a topographical map, of the structural types there are two different categories, single and centers. Single structures are those that stand alone they are, D, Dolmens; TU, Tumulus; T, Tomb; PA – Patio, W – Wall, CA – Cave, CIS - Cistern, S – Silo, P – Press, QS – Quarry Stone, C – Circle and SS – Standing Stone. Five major stunning discoveries relating to the dolmen culture is found. In rank of Importance, here are the discoveries: (1) borders and boundaries, show that each of the dolmen groups stand alone, (2) domestic meeting places point to a sedentary society, (3) quarries and cup hole cen- ters demonstrate a high scale of distribution of central places, and (4) ritualistic centers indicates a higher level of human relationship. -

A Preliminary Report on Megalithic Sites from Udumbanchola Taluk of Idukki District, Kerala

A Preliminary Report on Megalithic Sites from Udumbanchola Taluk of Idukki District, Kerala Sandra M. S. 1, Ajit Kumar1, Rajesh S.V. 1 and Abhayan G. S.1 1. Department of Archaeology, University of Kerala, Kariavattom Campus, Thiruvananthapuram – 695 581, Kerala, India (Email: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]; [email protected]) Received: 15 November 2017; Revised: 02 December 2017; Accepted: 29 December 2017 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 5 (2017): 519‐527 Abstract: As part of the MA Dissertation work, the first author explored the Udumbanchola taluk for megaliths. The exploration was productive and 41 new megalithic sites could be located. This article is a preliminary report on some interesting megalithic artifacts found during the exploration and also enlists the newly discovered sites. Keywords: Megalithic, Udumbanchola, Kallimali, Pot, Goblet, Neolithic Celt, Crucible Introduction Udumbanchola taluk (09° 53 ̍ 57. 68 ̎ N and 077°10 ̍ 53. 33 ̎ E) is located in the Idukki district. Nedumkandam is the major town and administrative headquarter of Udumbanchola taluk. This taluk borders with Tamil Nadu on the east. Due to large scale of migration from other parts of Kerala and Tamil Nadu, this taluk is melting pot of Kerala and Tamil cultures. This area is also inhabited by various ethnic tribes like Mannan, Muthuvan, Urali, Paliyan, Hilpulayan, Malapandaram, Ulladan, Malayan etc. Some archaeological explorations have been conducted in the taluk in the past and 16 sites have been reported from here. Though the prehistory of Idukki is still shrouded in obscurity, we get evidence of megalithic‐early historic cultures from Idukki district. -

Artisans in the Service of the Royalty at Dendra and Their Role in the Formation of Fashion Trends

Artisans in the Service of the Royalty at Dendra and their Role in the Formation of Fashion Trends Eleni Konstantinidi-Syvridi1 Abstract: Through its remarkable finds the necropolis at Dendra, covering the periods LH IIB–IIIB, offers an eloquent picture of the luxury possessed by the aristocracy up to the final phase of the early Mycenaean period. It is a time when art and crafts shift away from the hitherto Minoan influences to create forms and symbols that are purely Mycenaean, in search of a new identity. Metalwork of an advanced workmanship, testifying to the presence of highly skilled craftsmen, furnished the distinguished deceased in the necropolis. Craftsmen in the service of the elite seem to have circulated between various areas of the Aegean and Cyprus, forming through their creations common codes between its members. Being one of the few unplundered tholoi of the period, the Dendra tomb gathers most of those features that became fashionable in art and crafts among the early Mycenaean elite. A re-evaluation of the grave goods can therefore provide the impetus for a discussion on the production, manufacture and trade of luxurious items, especially metalwork, at the threshold of the Mycenaean Palatial period. Keywords: Dendra, warrior burials, metalwork, metal vessels, tholos tombs Within the fragile socio-political landscape of the early Mycenaean period, the elite families fought for the establishment of their political and economic power over the region,2 and at the same time shared a network of common values and symbols of