Unit 1 Reconstructing Ancient Society with Special

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Agricultural and Rural Development in India: a Rejoinder --Shambhu Ghatak

Agricultural and Rural Development in India: A Rejoinder --Shambhu Ghatak Keywords: Agricultural and rural development; Food security; Nutrition; NFHS III; Right to food; NREGS; Interlocking; Zamindari ; Liberalisation; High yielding varieties; Green Revolution; Livelihoods; Intellectual property rights; World Trade Organisation; Plant Variety Protection and Farmers' Rights Act; International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants; Regional Rural Banks; Scheduled Commercial Banks; Co- operatives; green house gases; Multi national corporations; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Small and marginal farmers; Minimum support price; Right to Information; People’s Union for Civil Liberties; Right to Development; World Food Summit; International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights; Human rights; Public distribution system; Starvation Introduction The primary focus of the present article is agricultural and rural development in India, as the title suggests. The article has attempted to address issues related to agricultural development, food security, poverty reduction and livelihoods generation. Keeping an area as huge as this at the center-stage of policy debates and discussion is important since a vast majority derives their livelihoods from agriculture, and they reside in rural India. The author has touched upon various issues related to agricultural development, which include: a. Labour market in India; b. Political economy of Indian agriculture; c. Indian agriculture before and after liberalization; d. The rural farm economy; e. Agrarian crisis and ‘liberal’ policies; f. Farmers’ suicides and its causes; g. Sustainability of Indian agriculture; h. Recent policy measures; i. Rural livelihoods and social audits; j. Agricultural R&D; k. Right to development; and, l. PDS, poverty and hunger in India. -

Accidental Prime Minister

THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE MAKING AND UNMAKING OF MANMOHAN SINGH SANJAYA BARU VIKING Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Group (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Offi ce Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offi ces: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published in Viking by Penguin Books India 2014 Copyright © Sanjaya Baru 2014 All rights reserved 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verifi ed to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. ISBN 9780670086740 Typeset in Bembo by R. Ajith Kumar, New Delhi Printed at Thomson Press India Ltd, New Delhi This book is sold subject to the condition that -

Bhoga-Bhaagya-Yogyata Lakshmi

BHOGA-BHAAGYA-YOGYATA LAKSHMI ( FULFILLMENT AS ONE DESERVES) Edited, compiled, and translated by VDN Rao, Retd. General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organization, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, currently at Chennai 1 Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda-Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu Essence of Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana Essence of Paraashara Smtiti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Dharma Bindu Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence of Narada Charitra; Essence Neeti Chandrika-Essence of Hindu Festivals and Austerities- Essence of Manu Smriti*- Quintessence of Manu Smriti* - *Essence of Pratyaksha Bhaskara- Essence of Maha Narayanopanishad*-Essence of Vidya-Vigjnaana-Vaak Devi* Note: All the above Scriptures already released on www. -

University College of Commerce & Management

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE & MANAGEMENT STUDIES MOHANLAL SUKHADIA UNIVERSITY, UDAIPUR. ELECTORAL LIST- 2016-17 B.COM. FIRST YEAR S. No. Name of Applicant Father Name ADDRESS 1 AAFREEN ARA ASHFAQ AHMED 113 nag marg outside chandpol 2 AAFREEN SHEIKH SHAFIQ AHMED SHEIKH 51 RAJA NAGAR SEC 12 SAVINA 3 AAISHA SIDDIKA MR.ABDUL HAMEED NAYA BAJAR KANORE THE-VALLABHNAGER DIS-UDAIPUR 4 AAKANKSHA KOTHARI PRAVEEN KUMAR KOTHARI 5, KANJI KA HATTA, GALI NO.1, OPP. SH DIG JAIN SCHOOL 5 AAKASH RATHOR ROSHAN LAL RATHOR 17 RAMDAWARA CHOWK BHUPALWARI UDAIPUR 6 AANCHAL ASHOK JAIN 61, A - BLOCK, HIRAN MAGRI SEC-14, UDAIPUR 7 AASHISH PATIDAR KAILASH PATIDAR VILL- DABOK 8 AASHRI KHATOD ANIL KHATOD 340,BASANT VIHAR,HIRAN MAGRI,SEC-5 9 AAYUSHI BANSAL UMESH BANSAL 4/543 RHB COLONY GOVERDHAN VILAS SEC. 14 UDAIPUR 10 AAYUSHI SINGH KACHAWA SHAKTI SINGH KACHAWA 1935/07 NEW RAMPURA COLONY SISARMA ROAD 11 ABHAY JAIN PRADEEP JAIN 18, GANESH GHATI, 12 ABHAY MEWARA SUBHASH CHANDRA MEWARA 874, MANDAKINIMARG BIJOLIYA 13 ABHISHEK DHABAI HEMANT DHABAI 209 OPP D E O SECOND GOVERDHAN VILLAS UDAIPUR 14 ABHISHEK JAIN PADAM JAIN HOUSE NO 632 SINGLE STORIE SEC 9 SAVINA 15 ABHISHEK KUMAR SINGH KHOOB SINGH 1/26 R.H.B. colony,Goverdhan Vilas,Udaipur(Raj.) 16 ABHISHEK PALIWAL KISHOR KALALI MOHALLA, CHHOTI SADRI 17 ABHISHEK SANADHYA DHAREMENDRA SANADHYA 47 ANAND VIHAR ROAD NO 2 TEKRI 18 ABHISHEK SETHIYA GOPAL LAL SETHIYA SADAR BAZAR RAILMAGRA 19 ABHISHEK SINGH RAO NARSINGH RAO 32-VIJAY SINGH PATHIK NAGAR SAVINA Page 1 of 186 20 ADITYA SINGH SISODIA BHARAT SINGH SISODIA 39, CHINTA MANI -

I Year Dkh11 : History of Tamilnadu Upto 1967 A.D

M.A. HISTORY - I YEAR DKH11 : HISTORY OF TAMILNADU UPTO 1967 A.D. SYLLABUS Unit - I Introduction : Influence of Geography and Topography on the History of Tamil Nadu - Sources of Tamil Nadu History - Races and Tribes - Pre-history of Tamil Nadu. SangamPeriod : Chronology of the Sangam - Early Pandyas – Administration, Economy, Trade and Commerce - Society - Religion - Art and Architecture. Unit - II The Kalabhras - The Early Pallavas, Origin - First Pandyan Empire - Later PallavasMahendravarma and Narasimhavarman, Pallava’s Administration, Society, Religion, Literature, Art and Architecture. The CholaEmpire : The Imperial Cholas and the Chalukya Cholas, Administration, Society, Education and Literature. Second PandyanEmpire : Political History, Administration, Social Life, Art and Architecture. Unit - III Madurai Sultanate - Tamil Nadu under Vijayanagar Ruler : Administration and Society, Economy, Trade and Commerce, Religion, Art and Architecture - Battle of Talikota 1565 - Kumarakampana’s expedition to Tamil Nadu. Nayakas of Madurai - ViswanathaNayak, MuthuVirappaNayak, TirumalaNayak, Mangammal, Meenakshi. Nayakas of Tanjore :SevappaNayak, RaghunathaNayak, VijayaRaghavaNayak. Nayak of Jingi : VaiyappaTubakiKrishnappa, Krishnappa I, Krishnappa II, Nayak Administration, Life of the people - Culture, Art and Architecture. The Setupatis of Ramanathapuram - Marathas of Tanjore - Ekoji, Serfoji, Tukoji, Serfoji II, Sivaji III - The Europeans in Tamil Nadu. Unit - IV Tamil Nadu under the Nawabs of Arcot - The Carnatic Wars, Administration under the Nawabs - The Mysoreans in Tamil Nadu - The Poligari System - The South Indian Rebellion - The Vellore Mutini- The Land Revenue Administration and Famine Policy - Education under the Company - Growth of Language and Literature in 19th and 20th centuries - Organization of Judiciary - Self Respect Movement. Unit - V Tamil Nadu in Freedom Struggle - Tamil Nadu under Rajaji and Kamaraj - Growth of Education - Anti Hindi & Agitation. -

1. Introduction

Notes 1. Introduction 1. ‘Diaras and Chars often first appear as thin slivers of sand. On this is deposited layers of silt till a low bank is consolidated. Tamarisk bushes, a spiny grass, establish a foot-hold and accretions as soon as the river recedes in winter; the river flows being considerably seasonal. For several years the Diara and Char may be cultivable only in winter, till with a fresh flood either the level is raised above the normal flood level or the accretion is diluvated completely’ (Haroun er Rashid, Geography of Bangladesh (Dhaka, 1991), p. 18). 2. For notes on geological processes of land formation and sedimentation in the Bengal delta, see W.W. Hunter, Imperial Gazetteer of India, vol. 4 (London, 1885), pp. 24–8; Radhakamal Mukerjee, The Changing Face of Bengal: a Study in Riverine Economy (Calcutta,1938), pp. 228–9; Colin D. Woodroffe, Coasts: Form, Process and Evolution (Cambridge, 2002), pp. 340, 351; Ashraf Uddin and Neil Lundberg, ‘Cenozoic History of the Himalayan-Bengal System: Sand Composition in the Bengal Basin, Bangladesh’, Geological Society of America Bulletin, 110 (4) (April 1998): 497–511; Liz Wilson and Brant Wilson, ‘Welcome to the Himalayan Orogeny’, http://www.geo.arizona.edu/geo5xx/ geo527/Himalayas/, last accessed 17 December 2009. 3. Harry W. Blair, ‘Local Government and Rural Development in the Bengal Sundarbans: an Enquiry in Managing Common Property Resources’, Agriculture and Human Values, 7(2) (1990): 40. 4. Richard M. Eaton, The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier 1204–1760 (Berkeley and London, 1993), pp. 24–7. 5. -

I Mughal Empire

MPPSCADDA ATMANIRBHAR PT 100 DAYS - HISTORY MPPSC PRELIMS 2020 ATMANIRBHAR PROGRAM PRELIMS QUICK REVISION NOTES HISTORY DAY 40 - EARLY- MEDIEVAL PERIOD (8th-12th Century) THE RAJPUTS Some Important Rajputs Kingdoms IMPORTANT RAJPUTS DYNASTIES o The Pawar/Parmar of Malwa: 790-1036 AD o The Gahadval/Rathor of Kannauj : 1090-1194AD o The Chauhans/Chahaman of Delhi-Ajmer: 7th -12th Century AD o The Karkota, Utpala and Lohara of Kashmir : 800-1200 AD ) o The Chandellas of Jejakabhukti: 831-1202 AD o The Senas : 1095-1230 AD o The Guhilota/Sisodiya of Mewar: 8th - 20th Century AD o Tomars of Delhi : 736 AD Salient features of the Rajput Kingdoms. Causes of the Decline of Rajputas ARAB CONQUEST OF SIND (712-1206 AD) MEDIEVAL INDIA The Medieval period of Indian History: This period lies between 8th and 18th century AD and is classified as : The Early Medieval period (8th to 12th century AD) The Later Medieval period (13th to 18th century AD). EARLY- MEDIEVAL PERIOD (8th to 12th Century) The Ancient Indian history came to an end with the rule of Harsha and Pulakeshin-II. From the death of Harsha to the 12th century, the destiny of India was mostly in the hands of various Rajput dynasties. MPPSCADDA THE RAJPUTS Different theories about the origin of the Rajputs : (i) They are the descendants of Lord Rama (Surya Vansha) or Lord Krishna (Chandra Vansha) or the hero who sprang from the sacrificial fire (Agni Kula theory). (ii) They belong to the Kshatriya families. (iii) The most accepted theory is that Rajputs were of a foreign origin, who came as conquerors and settled in West India. -

College of William and Mary Department of Economics Working Paper Number 137

The Labor/Land Ratio and India’s Caste System Harriet Orcutt Duleep (Thomas Jefferson Program in Public Policy, College of William and Mary and IZA- Institute for the Study of Labor) College of William and Mary Department of Economics Working Paper Number 137 March 2013 COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER # 137 March 2013 The Labor/Land Ratio and India’s Caste System Abstract This paper proposes that India’s caste system and involuntary labor were joint responses by a nonworking landowning class to a low labor/land ratio in which the rules of the caste system supported the institution of involuntary labor. The hypothesis is tested in two ways: longitudinally, with data from ancient religious texts, and cross-sectionally, with twentieth-century statistics on regional population/land ratios linked to anthropological measures of caste-system rigidity. Both the longitudinal and cross-sectional evidence suggest that the labor/land ratio affected the caste system’s development, persistence, and rigidity over time and across regions of India. JEL Codes: J47, J1, J30, N3, Z13 Keywords: labor-to-land ratio, population, involuntary labor, immobility, value of life, marginal product of labor, market wage Harriet Duleep Thomas Jefferson Program in Public Policy College of William and Mary Williamsburg VA 23187-8795 [email protected] The Labor/Land Ratio and India’s Caste System I. Background Several scholars have observed that, historically, the caste system was more rigid in south India than in other parts of India. In the 1930’s, Gunther (1939, p. 378) described south India as the “...home of Hinduism in its most intensive form...virtually a disease... -

Subject: EVOLUTION of SOCIAL STRUCTURE in INDIA: THROUGH the AGES Credits: 4 SYLLABUS

Subject: EVOLUTION OF SOCIAL STRUCTURE IN INDIA: THROUGH THE AGES Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Introductory & Cultures in Transition Harappan Civilisation and other Chalcolithic Cultures, Hunting-Gathering, Early Farming Society, Pastoralism, Reconstructing Ancient Society with Special Reference to Sources, Emergence of Buddhist Central And Peninsular India, Socio-Religious Ferment In North India: Buddhism And Jainism, Iron Age Cultures, Societies Represented In Vedic Literature Early Medieval Societies & Early Historic Societies: 6th Century - 4th Century A.D Religion in Society, Proliferation and consolidation of Castes and Jatis, The Problem of Urban Decline: Agrarian Expansion, Land Grants and Growth of Intermediaries, Transition To Early Medieval Societies, Marriage and Family Life,Notions of Untouchability, Changing Patterns in Varna and Jati, Early Tamil Society –Regions and Their Cultures and Cult of Hero Worship, Chaityas, Viharas and Their Interaction with Tribal Groups, Urban Classes: Traders and Artisans, Extension of Agricultural Settlements Medieval Society & Society on the Eve of Colonialism Rural Society: Peninsular India, Rural Society: North India, Village Community, The Eighteenth Century Society in Transition, Socio Religious Movements, Changing Social Structure in Peninsular India, Urban Social Groups in North India, Modern Society & Social Questions under Colonialism Social Structure in The Urban and Rural Areas, Pattern of Rural-Urban Mobility: Overseas Migration, Studying Castes in The New Historical Context, Perceptions of The Indian Social Structure by The Nationalists and Social Reformers, Clans and Confederacies in Western India, Studying Tribes Under Colonialism, Popular Protests and Social Structures, Social Discrimination, Gender/Women Under Colonialism, Colonial Forest Policies and Criminal Tribes Suggested Reading: 1. Nation, Nationalism and Social Structure in Ancient India : Shiva Acharya 2. -

Society and Economy During Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: an Archaeological Perspective

Society and Economy during Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: An Archaeological Perspective Tilok Thakuria1 1. Department of History and Archaeology, North Eastern Hill University, Tura Campus, Meghalaya – 794002, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 31July 2017; Revised: 29September 2017; Accepted: 09November 2017 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 5 (2017): 169‐190 Abstract: The paper aims to analyze the archaeological evidence to understand the social and economic formation during the Early Historic period in Maharashtra. The analysis and discussion offered in the paper are based mainly on archaeological evidences unearthed in excavations. However, historical information were also taken into consideration for verification and understanding of archaeological evidence. Keywords: Early History, Megalithic, Pre‐Mauryan, Satavahana, Society, Economy, Maharashtra Introduction History and archaeology need to grow together, instead of parallel, by sharing and utilizing sources as the primary aim of both is to write history. According to Thapar (1984: 193‐194) “The study of social history, economic history and the role of technology in Indian history, being comparatively new to the concern of both archaeologist and historians, require appropriate emphasis. Furthermore, in these fields, the evidence from archaeology can be used more directly. The historian has data on these aspects from literary sources but the data tends to be impressionistic and confined by the context. Archaeology can provide the historian with more precise data on the fundamentals of these aspects of history, resulting thereby in a better comprehension of the early forms of socio‐economic institutions”. The social and economic conditions of Maharashtra during the early historic period have been reconstructed mostly based on available sources like inscriptions, coins and travelers’ accounts. -

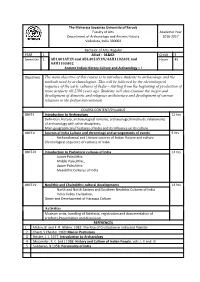

Objectives the Main Objective of This Course Is to Introduce Students to Archaeology and the Methods Used by Archaeologists

The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Faculty of Arts Academic Year Department of Archaeology and Ancient History 2016-2017 Vadodara, India 390002 Bachelor of Arts: Regular YEAR 1 Allied - 01&02: Credit 3 Semester 1 AB1A01AY1N and AB1A02AY1N/AAH1102A01 and Hours 45 AAH1103A02 Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology – I Objectives The main objective of this course is to introduce students to archaeology and the methods used by archaeologists. This will be followed by the chronological sequence of the early cultures of India – starting from the beginning of production of stone artifacts till 2700 years ago. Students will also examine the origin and development of domestic and religious architecture and development of various religions in the Indian subcontinent COURSE CONTENT/SYLLABUS UNIT-I Introduction to Archaeology 12 hrs Definition, history, archaeological remains, archaeological methods, relationship of archaeology with other disciplines; Main geographical of features of India and its influence on its culture UNIT-II Sources of India Culture and chronology and arrangements of events 5 hrs Archaeological and Literary sources of Indian History and culture Chronological sequence of cultures of India UNIT-III Introduction to Prehistoric cultures of India 14 hrs Lower Paleolithic, Middle Paleolithic, Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic Cultures of India UNIT-IV Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultural developments 14 hrs North and North Eastern and Southern Neolithic Cultures of India Indus Valley Civilization, Origin and Development of Harappa Culture Activities Museum visits, handling of Artefacts, registration and documentation of artefacts,Presentation and discussion REFERENCES 1 Allchin, B. and F. R. Allchin. 1982. The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan.