Stoneware Craft of Patharkatti Village, Part-VII-A, Vol-IV, Bihar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dialogue of Craft and Architecture

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses Dissertations and Theses July 2015 The Dialogue of Craft and Architecture Thomas J. Forker University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2 Part of the Architectural Technology Commons, and the Cultural Resource Management and Policy Analysis Commons Recommended Citation Forker, Thomas J., "The Dialogue of Craft and Architecture" (2015). Masters Theses. 197. https://doi.org/10.7275/7044176 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/masters_theses_2/197 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DIALOGUE OF CRAFT AND ARCHITECTURE A Thesis Presented by THOMAS J. FORKER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE MAY 2015 DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE THE DIALOGUE OF CRAFT AND ARCHITECTURE A Thesis Presented by THOMAS J. FORKER Approved as to style and content by: ___________________________ Kathleen Lugosch, Chair ___________________________ Ray Mann, Associate Professor ____________________ Professor Kathleen Lugosch Graduate Program Director Department of Architecture ____________________ Professor Stephen Schreiber Chair Department of Architecture DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents, for their love and support. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my professors Kathleen Lugosch and Ray Mann. They have been forthright with their knowledge, understanding, and dedicated in their endeavor to work with the students in the department and in the pursuit of a masters of architecture degree with spirit and meaning. -

University College of Commerce & Management

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE & MANAGEMENT STUDIES MOHANLAL SUKHADIA UNIVERSITY, UDAIPUR. ELECTORAL LIST- 2016-17 B.COM. FIRST YEAR S. No. Name of Applicant Father Name ADDRESS 1 AAFREEN ARA ASHFAQ AHMED 113 nag marg outside chandpol 2 AAFREEN SHEIKH SHAFIQ AHMED SHEIKH 51 RAJA NAGAR SEC 12 SAVINA 3 AAISHA SIDDIKA MR.ABDUL HAMEED NAYA BAJAR KANORE THE-VALLABHNAGER DIS-UDAIPUR 4 AAKANKSHA KOTHARI PRAVEEN KUMAR KOTHARI 5, KANJI KA HATTA, GALI NO.1, OPP. SH DIG JAIN SCHOOL 5 AAKASH RATHOR ROSHAN LAL RATHOR 17 RAMDAWARA CHOWK BHUPALWARI UDAIPUR 6 AANCHAL ASHOK JAIN 61, A - BLOCK, HIRAN MAGRI SEC-14, UDAIPUR 7 AASHISH PATIDAR KAILASH PATIDAR VILL- DABOK 8 AASHRI KHATOD ANIL KHATOD 340,BASANT VIHAR,HIRAN MAGRI,SEC-5 9 AAYUSHI BANSAL UMESH BANSAL 4/543 RHB COLONY GOVERDHAN VILAS SEC. 14 UDAIPUR 10 AAYUSHI SINGH KACHAWA SHAKTI SINGH KACHAWA 1935/07 NEW RAMPURA COLONY SISARMA ROAD 11 ABHAY JAIN PRADEEP JAIN 18, GANESH GHATI, 12 ABHAY MEWARA SUBHASH CHANDRA MEWARA 874, MANDAKINIMARG BIJOLIYA 13 ABHISHEK DHABAI HEMANT DHABAI 209 OPP D E O SECOND GOVERDHAN VILLAS UDAIPUR 14 ABHISHEK JAIN PADAM JAIN HOUSE NO 632 SINGLE STORIE SEC 9 SAVINA 15 ABHISHEK KUMAR SINGH KHOOB SINGH 1/26 R.H.B. colony,Goverdhan Vilas,Udaipur(Raj.) 16 ABHISHEK PALIWAL KISHOR KALALI MOHALLA, CHHOTI SADRI 17 ABHISHEK SANADHYA DHAREMENDRA SANADHYA 47 ANAND VIHAR ROAD NO 2 TEKRI 18 ABHISHEK SETHIYA GOPAL LAL SETHIYA SADAR BAZAR RAILMAGRA 19 ABHISHEK SINGH RAO NARSINGH RAO 32-VIJAY SINGH PATHIK NAGAR SAVINA Page 1 of 186 20 ADITYA SINGH SISODIA BHARAT SINGH SISODIA 39, CHINTA MANI -

Samwaad Importance of Tourism Industry in Bihar

Samwaad: e-Journal ISSN: 2277-7490 2017: Vol. 6 Iss. 2 Importance of Tourism Industry in Bihar Dr. Ashok Kumar Department of commerce, Rnym College, Barhi Vbu Hazribag Email :- drashokkumarhzb@gmailcom Abstract Tourism is an important source of Entertainment and revenue generation of government now a days each and every person wants to visit tourist places where he/she get enjoyment and earns some knowledge about new areas, and location. Tourist places are developed for many factors like-historical place, cold place, moderate climate, natural sceneries, lake, pond, sea beach, hilly area, Island, religious and political importance etc. these are the factors which attract tourist. Tourist places also create so many job opportunities like, tourist guide, Hotels, airlines railways, sports, worship material etc. for speedy development in speed way government has announced tourism as Tourism industry. Another significance is that it helps the govt to generate foreign currency. Tourism is also helpful in the area of solving the unemployment problem. Migration is not in affect by tourism because where so many people of employment but it own houses for many purpose like, residence , Hotel, shop, museum, cinema hall, market complex, etc. Near by the tourist place migration ends or decreases but only few exception cases where migration problem creates otherwise tourism solve the problem. Key words :- Entertainment, Tourist, Government, Migration problem. etc. Samwaad http://samwaad.in Page 103 of 193 Samwaad: e-Journal ISSN: 2277-7490 2017: Vol. 6 Iss. 2 Introduction Bihar in eastern India is one of the oldest inhabited places in the world with a history going back 3000 years. -

Ayurvedic Section

Ayurvedic Section: S.NO. NAME OF THE DEPARTMENT 1. MAULIK SIDDHANT (Basic Principles) 2. RACHNA SHARIR (Anatomy) 3. KRIYA SHARIR (Physiology) 4. DRAVYAGUNA (Pharmacology and Materia Medica) 5. RASA SHASTRA (Pharmaceutical science) 6. ROG NIDAN (Pathology) 7. SWASTHYAVRITTA((Preventive and Social MediCine & Yoga) 8. AGAD TANTRA(Medical Jurisprudence & Toxicology) 9. PRASUTI & STRIROGA (Obstetrics & Gynaecology.) 10. KAUMARBHARATYA (Paediatrics) 11. KAYACHIKITSA(Ayurved Medicine) 12. SHALYA(Surgery) 13. SHALAKYA TANTRA(Eye & ENT) 14. PANCHAKARMA Name of the department : Samhita-Siddhant-Sanskrit Introduction to the department- Deals with Basic principles of Ayurved which is the root of ayurvedic medicines. Faculties- 1) Dr. Nishi Arora, MD, PhD (Ayurveda), PGDCFT (Associate professor) 2) Dr.Kousik Das Mahapatra, MD, PhD(Ayurveda), PGDCFT (Lecturer) 3) Mrs.Mukta, M.A., PhD in Sanskrit(Lecturer) 4) Dr. Sangeeta Mishra ,MD,PhD Available equipments- Chart-30, Models-10 Departmental activities regular classes (40/week), Departmental seminar (Once in amonth), CME conducted in 2015 Publications- 1) Dr. Nishi Arora, MD, PhD (Ayurveda), PGDCFT (Associate professor)- 3 books. 2) Dr.Kousik Das Mahapatra, MD, PhD(Ayurveda), PGDCFT (Lecturer)- 2 books, 20 scientific papers Research ongoing Multi-dimensional study on Diabetes Details of Faculty Sl.No. Name of the Qualification Date of Present Contact. No. Photo faculty joining Designation 1. Dr. Nishi , MD, PhD, 29/03/2001 Associate 9871050255 Arora PGDCFT professor 2. Dr. Kousik , MD, PhD, 16/09/2010 Lecturer 9582464064 Das PGDCFT Mahapatra 3. Mrs.Mukta, M.A., PhD Lecturer 9013320845 Guest Part time Faculty 4. Dr. Sangeeta M.D, PhD 08/04/2016 Assistant 9468457364 Mishra Professor NAME OF DEPARTMENT - RACHNA SHARIR INTRODUCTION TO THE DEPARTMENT- Rachna Sharir is first year subject of ayurved professional. -

AEAH 4840 TOPICS, CRAFT 4840. Topics in the History of Crafts. 3

Instructor: Professor Way Term: Spring 2017 Office: Art Building 212 Class time: Monday 5:00-7:50pm Office Hours: please schedule in advance through email Meeting Place: Art 226 Monday, 4:00-5:00, Tuesday 4:00-5:00, Thursday 4:00-5:00 Email: [email protected] – best way to reach me AEAH 4840 TOPICS, CRAFT 4840. Topics in the History of Crafts. 3 hours. Selected topics in the history of crafts. Prerequisite(s): ART 1200 or 1301, 2350 and 2360, or consent of instructor. TOPIC – CRITICAL HISTORIES OF CRAFT AND ART HISTORY This course explores how history of art survey texts represent and tell us about craft—what do they have to say about craft, and how do they say it? We are equally interested in where and how these art history survey texts neglect craft. What is missing when histories of art do not include craft? Additionally, we want to think about history of craft texts. Should they include the same agents and situations we find in histories of art, such as famous makers and collectors, the rich and the royal, politics at the highest level, and economics, power, and desire? Also, is it possible to trace influence in craft as we expect to find it discussed in histories of art? What would influence explain about craft? Should a history of craft include features we don’t expect to find in histories of art? Overall, what scholarship and methods make a history of craft? These types of questions ask us to notice standards and expectations shaping knowledge in academic fields, such as art history and the history of craft. -

Crossing the Divide Between Art and Craft

Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato Volume 10 Article 4 2010 Crossing the Divide between Art and Craft Kristin Harsma Minnesota State University, Mankato Follow this and additional works at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur Part of the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Harsma, Kristin (2010) "Crossing the Divide between Art and Craft," Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato: Vol. 10 , Article 4. Available at: https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/jur/vol10/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Research Center at Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato by an authorized editor of Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato. Harsma: Crossing the Divide between Art and Craft Crossing the Divide Between Art and Craft Kristin Harsma Minnesota State University Faculty Mentor: Curt Germundson April 6, 2010 Published by Cornerstone: A Collection of Scholarly and Creative Works for Minnesota State University, Mankato, 2010 1 Journal of Undergraduate Research at Minnesota State University, Mankato, Vol. 10 [2010], Art. 4 Crossing the Divide Between Art and Craft Kristin J. Harsma (Arts and Humanities) Curt Germundson, Faculty Mentor (Arts and Humanities) Throughout history, various qualities of art have gone in and out of fashion, works declared high art being considered most important. However, there has always been a hierarchy of not only subjects of art but also of media used to create art. -

The Evolution of Craft in Contemporary Feminist Art

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2010 The volutE ion of Craft in onC temporary Feminist Art Carolyn E. Packer Scripps College Recommended Citation Packer, Carolyn E., "The vE olution of Craft in onC temporary Feminist Art" (2010). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 23. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/23 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Evolution of Craft in Contemporary Feminist Art By: Carolyn Elizabeth Packer SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS Professor Susan Rankaitis Professor Nancy Macko May 3, 2010 This Senior Project is dedicated to my Grandmother, Gloria Carolyn Reich. Thank you for giving me the invaluable skills that have inspired my art and being the model for woman I strive to become. Thank you also to Professor Susan Rankaitis for inspiring my dedication to this project, and to Professor Nancy Macko for being such a supportive and encouraging advisor, thesis reader, and role model. 2 Women’s art is rooted in a long history of traditional craft practices. It is said that during the times of male-dominated society, if a woman had any brains she would explore her creativity through quilting, clothing design and needlework; creating utilitarian objects for the household to serve her husband and family. Being a part of an extended family lineage of talented and inspired craftswomen has provoked me to analyze the evolution of craft from a domestic practice into a higher form of feminist art. -

Unit 1 Reconstructing Ancient Society with Special

Harappan Civilisation and UNIT 1 RECONSTRUCTING ANCIENT Other Chalcolithic SOCIETY WITH SPECIAL Cultures REFERENCE TO SOURCES Structure 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Sources 1.1.1 Epigraphy 1.1.2 Numismatics 1.1.3 Archaeology 1.1.4 Literature 1.2 Interpretation 1.3 The Ancient Society: Anthropological Readings 1.4 Nature of Archaeology 1.5 Textual Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Glossary 1.8 Exercises 1.0 INTRODUCTION The primary objective of this unit is to acquaint the learner with the interpretations of the sources that reveal the nature of the ancient society. We therefore need to define the meaning of the term ‘ancient society’ to begin with and then move on to define a loose chronology in the context of the sources and their readings. It would also be useful to have an understanding about the various readings of the sources, a kind of a historiography of the interpretative regime. In order to facilitate a better understanding this unit is divided into five sections. In the introduction we have discussed the range of interpretations that are deployed on the sources and often the sources also become interpretative in nature. The complexity of the sources has also been dealt with in the same context. The new section then discusses the ancient society and what it means. This discussion is spread across the regions and the varying sources that range from archaeology to oral traditions. The last section then gives some concluding remarks. 1.1 SOURCES Here we introduce you to different kinds of sources that help us reconstruct the social structure. -

Subject: EVOLUTION of SOCIAL STRUCTURE in INDIA: THROUGH the AGES Credits: 4 SYLLABUS

Subject: EVOLUTION OF SOCIAL STRUCTURE IN INDIA: THROUGH THE AGES Credits: 4 SYLLABUS Introductory & Cultures in Transition Harappan Civilisation and other Chalcolithic Cultures, Hunting-Gathering, Early Farming Society, Pastoralism, Reconstructing Ancient Society with Special Reference to Sources, Emergence of Buddhist Central And Peninsular India, Socio-Religious Ferment In North India: Buddhism And Jainism, Iron Age Cultures, Societies Represented In Vedic Literature Early Medieval Societies & Early Historic Societies: 6th Century - 4th Century A.D Religion in Society, Proliferation and consolidation of Castes and Jatis, The Problem of Urban Decline: Agrarian Expansion, Land Grants and Growth of Intermediaries, Transition To Early Medieval Societies, Marriage and Family Life,Notions of Untouchability, Changing Patterns in Varna and Jati, Early Tamil Society –Regions and Their Cultures and Cult of Hero Worship, Chaityas, Viharas and Their Interaction with Tribal Groups, Urban Classes: Traders and Artisans, Extension of Agricultural Settlements Medieval Society & Society on the Eve of Colonialism Rural Society: Peninsular India, Rural Society: North India, Village Community, The Eighteenth Century Society in Transition, Socio Religious Movements, Changing Social Structure in Peninsular India, Urban Social Groups in North India, Modern Society & Social Questions under Colonialism Social Structure in The Urban and Rural Areas, Pattern of Rural-Urban Mobility: Overseas Migration, Studying Castes in The New Historical Context, Perceptions of The Indian Social Structure by The Nationalists and Social Reformers, Clans and Confederacies in Western India, Studying Tribes Under Colonialism, Popular Protests and Social Structures, Social Discrimination, Gender/Women Under Colonialism, Colonial Forest Policies and Criminal Tribes Suggested Reading: 1. Nation, Nationalism and Social Structure in Ancient India : Shiva Acharya 2. -

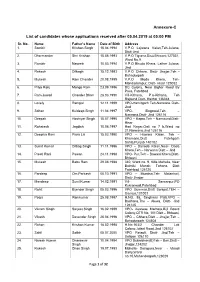

Annexure-C List of Candidates Whose Applications Received After 05.04

Annexure-C List of candidates whose applications received after 05.04.2019 at 05:00 PM Sr. No. Name Father’s Name Date of Birth Address 1. Sombir Krishan Singh 15.04.1994 V.P.O Lajwana Kalan,Teh-Julana, Distt-Jind 2. Dharmender Shri Krishan 15.08.1993 V.P.O Tigrana,Distt Bhiwani,127031, Ward No.9 3. Rambir Naseeb 10.03.1994 V.P.O Bhuda Khera, Lather Julana, Jind 4. Rakesh Dilbagh 15.12.1993 V.P.O Chhara, Distt- Jhajjar,Teh - Bahadurgarh 5. Mukesh Ram Chander 20.08.1995 V.P.O Moda Khera, Teh- Mandadampur, Distt- Hisar 125052 6. Priya Ranj Mange Ram 23.09.1996 DC Colony, Near Bighar Road By Pass, Fatehbad 7. Ram Juwari Chander Bhan 28.03.1990 Vill-Kithana, P.o-Kithana, Teh Rajaund,Distt- Kaithal 136044 8. Lovely Rampal 12.11.1999 VPO-Hamirgarh Teh-Narwana Distt- Jind 9. Sohan Kuldeep Singh 11.04.1997 VPO- Singowal,Teh – Narwana,Distt- Jind 126116 10. Deepak Hoshiyar Singh 15.07.1995 VPO – Kapro,Teh – Narnaund,Distt- Hisar 11. Rohatash Jagdish 10.06.1997 Hari Nagar,Gali no 7 b,Ward no 21,Narwana,Jind 126116 12. Deepika Rani Piara Lal 15.03.1990 VPO – Hawara Kalan, Teh – Khamano,Distt Fatehgarh Sahib,Punjab 140102 13. Sumit Kumar Dilbag Singh 11.11.1996 VPO – Danoda Kalan,Near- Dada Khera,Teh – Narwana Distt – Jind 14. Preeti Rani Pawan 24.11.1998 VPO- Pur,Teh – Bawani Khera,Distt- Bhiwani 15. Mukesh Babu Ram 29.08.1988 340, Ward no. 9, Killa Mohalla, Near Balmiki Mandir, Tohana, Distt Fatehbad 125120 16. -

Annual Report

JAIPUR VIRASAT FOUNDATION HERITAGE BASED SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2004-2005 Painting of the historic walled city of Jaipur commissioned by JVF -A CITY FESTIVAL TO DRIVE DEVELOPMENT- -A CONSERVATION BASED DEVELOPMENT INITIATIVE- -A VISION FOR SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN THE INDIAN CONTEXT- For its first three formative years (2002 - 2005), JVF has developed its objectives, strategies and structure under the umbrella of the Jaipur Heritage International Festival. For this report we present our activities under seven headings: Virasat Andolan (advocacy, awareness, community participation) Arts (conserving and documenting regional traditional arts) Buildings (conserving the historic built environment) Crafts (conserving traditional skills) Development (Best Practices to generate cultural industries) Education (engaging young people in the vision) Festival (to showcase the vision and demonstrate its economic potential) The seven headings represent the holistic nature of ongoing JVF activities. From 2005, JVF will engage increasingly with the built heritage and then with crafts. The seven headings provide the structure under which projects will be conceived and managed. As a citizens' initiative in response to the visible impact of modernisation on traditional communities and the consequent loss of cultural heritage, it is hoped that the pioneering work of JVF may grow as a model for other cities of India to help build a more equitable and sustainable future. pg.3 VIRASAT ANDOLAN JVF is committed to creating a heritage (virasat) movement (andolan ) among the people of Jaipur through advocacy, awareness programmes and engaging the community at all levels and opportunities. Regular meetings are held with experts and stakeholders, and every opportunity is taken to spread the virasat message and engage local people in the value and relevance of the region's extraordinary heritage. -

Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia October, 8-10, 2015 International Museum - Event Program

Fabergé Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia October, 8-10, 2015 International Museum - Event Program Section I. Fabergé’s Lapidary Art • Tatiana Muntian. Fabergé and His Flower Studies • Alexander von Solokoff. Rock Crystal Mushrooms by Fabergé • Valentin Skurlov. The Range of Products and Precious Stones in Fabergé’s Stone-Cutting Production (1890-1917) • Galina Korneva and Tatiana Cheboksarova. Stone Carvings in the Collection of the Great Duchess Maria Pavlovna • Pavel Kotlyar. Alexander Palace and the Fabergé Firm • Dmitriy Krivoshei. Stone-cut Objects and Clients of the Fabergé Company in 1909-1916’s (Based on General Ledger) • Svetlana Chestnykh. History of Hardstone Figure of Kamer-Kazak N.N. Pustynnikov Section II. Russian Lapidary Art in the 19th-Early 20th Centuries • Evgeniy Lukianov. Precious and Semi-precious Stones in Works of the Sazikov Firm (1850- 1880’s) • Andreiy Gilodo. Lapidary Art of Soviet Russia in 1920-1930’s • Ludmila Budrina. By Order of Mr. Governor: Ekaterinburg Lapidary Factory Items from 1880- 1890’s Made from Non-Chancery Designs • Natalia Borovkova. Works of the Ekaterinburg Lapidary Factory in 1870-1880's Commissioned by His Imperial Majesty's Own Chancery • Mariya Osipova. Stone Carvings of the Bolin Firm • Aleksandra Pestova. History of West Ural’s Stone Craft (1830-1930’s). Influence of Ekaterinburg Stone Carvers and Fabergé’s Craftsmen Section III. Origin of Russian Jeweler’s Art • Annette Fuhr. The Story of Idar-Oberstein, One of the Most Important Towns in the Gemstone World • Max Rutherston. Netsuke • Olga Alieva. Prototypes of Modern Ural Hardstone Sculpture • Raisa Lobatckaya. Siberian Ethnic Motives in Works of Modern Jewelers • Ekaterina Tarakanova.