Ancient Iron Making in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Art. I.—The Iron Pillar of Delhi

JOURNAL THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY. ART. I.— The Iron Pillar of Delhi (Mihrauli) and the Emperor Candra {Chandra). By VINCENT A. SMITH, M.R.A.S., Indian Civil Service. PREFATORY NOTE. THE project of writing the "Ancient History of Northern India from the Monuments" has long occupied my thoughts, but the duties of my office do not permit me, so long as I remain in active service, to devote the time and attention necessary for the execution and completion of so arduous an undertaking. There is, indeed, little prospect that my project will ever be fully carried into effect by me. Be that as it may, I have made some small progress in the collection of materials, and have been compelled from time to time to make detailed preparatory studies of special subjects. I propose to publish these studies occasionally under the general title of " Prolegomena to Ancient Indian History." The essay now presented as No. I of the series is that which happens to be the first ready. It grew out of a footnote to the draft of a chapter on the history of Candra Gupta II. V. A. SMITH, Gorakhpur, India. July, 1896. , J.K.A.S. 1897. x 1 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. INSEAD, on 14 Sep 2018 at 15:56:13, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0035869X00024205 2 THE IRON PILLAR OF DELHI. The great mosque built by Qutb-ud-din 'Ibak in 1191 A.D., and subsequently enlarged by his successors, as well as its minaret, the celebrated Qutb Mlnar, stand on the site of Hindu temples, and within the limits of the fortifications known as the Fort of Rai Pithaura, which were erected in the middle or latter part of the twelfth century to protect the Hindu city of Delhi from the attacks of the Musalmans, who finally captured it in A.D. -

Teacher Overview: What Led to the Gupta Golden Age? How Did The

Please Read: We encourage all teachers to modify the materials to meet the needs of their students. To create a version of this document that you can edit: 1. Make sure you are signed into a Google account when you are on the resource. 2. Go to the "File" pull down menu in the upper left hand corner and select "Make a Copy." This will give you a version of the document that you own and can modify. Teacher Overview: What led to the Gupta Golden Age? How did the Gupta Golden Age impact India, other regions, and later periods in history? Unit Essential Question(s): How did classical civilizations gain, consolidate, maintain and lose their power? | Link to Unit Supporting Question(s): ● What led to the Gupta Golden Age? How did the Gupta Golden Age impact India, other regions, and later periods in history? Objective(s): ● Contextualize the Gupta Golden Age. ● Explain the impact of the Gupta Golden Age on India, other regions, and later periods in history. Go directly to student-facing materials! Alignment to State Standards 1. NYS Social Studies Framework: Key Idea Conceptual Understandings Content Specifications 9.3 CLASSICAL CIVILIZATIONS: 9.3c A period of peace, prosperity, and Students will examine the achievements EXPANSION, ACHIEVEMENT, DECLINE: cultural achievements can be designated of Greece, Gupta, Han Dynasty, Maya, Classical civilizations in Eurasia and as a Golden Age. and Rome to determine if the civilizations Mesoamerica employed a variety of experienced a Golden Age. methods to expand and maintain control over vast territories. They developed lasting cultural achievements. -

History of India

HISTORY OF INDIA VOLUME - 2 History of India Edited by A. V. Williams Jackson, Ph.D., LL.D., Professor of Indo-Iranian Languages in Columbia University Volume 2 – From the Sixth Century B.C. to the Mohammedan Conquest, Including the Invasion of Alexander the Great By: Vincent A. Smith, M.A., M.R.A.S., F.R.N.S. Late of the Indian Civil Service, Author of “Asoka, the Buddhist Emperor of India” 1906 Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2018) Preface by the Editor This volume covers the interesting period from the century in which Buddha appeared down to the first centuries after the Mohammedans entered India, or, roughly speaking, from 600 B.C. to 1200 A.D. During this long era India, now Aryanized, was brought into closer contact with the outer world. The invasion of Alexander the Great gave her at least a touch of the West; the spread of Buddhism and the growth of trade created new relations with China and Central Asia; and, toward the close of the period, the great movements which had their origin in Arabia brought her under the influences which affected the East historically after the rise of Islam. In no previous work will the reader find so thorough and so comprehensive a description as Mr. Vincent Smith has given of Alexander’s inroad into India and of his exploits which stirred, even if they did not deeply move, the soul of India; nor has there existed hitherto so full an account of the great rulers, Chandragupta, Asoka, and Harsha, each of whom made famous the age in which he lived. -

Unit 1 Reconstructing Ancient Society with Special

Harappan Civilisation and UNIT 1 RECONSTRUCTING ANCIENT Other Chalcolithic SOCIETY WITH SPECIAL Cultures REFERENCE TO SOURCES Structure 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Sources 1.1.1 Epigraphy 1.1.2 Numismatics 1.1.3 Archaeology 1.1.4 Literature 1.2 Interpretation 1.3 The Ancient Society: Anthropological Readings 1.4 Nature of Archaeology 1.5 Textual Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Glossary 1.8 Exercises 1.0 INTRODUCTION The primary objective of this unit is to acquaint the learner with the interpretations of the sources that reveal the nature of the ancient society. We therefore need to define the meaning of the term ‘ancient society’ to begin with and then move on to define a loose chronology in the context of the sources and their readings. It would also be useful to have an understanding about the various readings of the sources, a kind of a historiography of the interpretative regime. In order to facilitate a better understanding this unit is divided into five sections. In the introduction we have discussed the range of interpretations that are deployed on the sources and often the sources also become interpretative in nature. The complexity of the sources has also been dealt with in the same context. The new section then discusses the ancient society and what it means. This discussion is spread across the regions and the varying sources that range from archaeology to oral traditions. The last section then gives some concluding remarks. 1.1 SOURCES Here we introduce you to different kinds of sources that help us reconstruct the social structure. -

Society and Economy During Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: an Archaeological Perspective

Society and Economy during Early Historic Period in Maharashtra: An Archaeological Perspective Tilok Thakuria1 1. Department of History and Archaeology, North Eastern Hill University, Tura Campus, Meghalaya – 794002, India (Email: [email protected]) Received: 31July 2017; Revised: 29September 2017; Accepted: 09November 2017 Heritage: Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies in Archaeology 5 (2017): 169‐190 Abstract: The paper aims to analyze the archaeological evidence to understand the social and economic formation during the Early Historic period in Maharashtra. The analysis and discussion offered in the paper are based mainly on archaeological evidences unearthed in excavations. However, historical information were also taken into consideration for verification and understanding of archaeological evidence. Keywords: Early History, Megalithic, Pre‐Mauryan, Satavahana, Society, Economy, Maharashtra Introduction History and archaeology need to grow together, instead of parallel, by sharing and utilizing sources as the primary aim of both is to write history. According to Thapar (1984: 193‐194) “The study of social history, economic history and the role of technology in Indian history, being comparatively new to the concern of both archaeologist and historians, require appropriate emphasis. Furthermore, in these fields, the evidence from archaeology can be used more directly. The historian has data on these aspects from literary sources but the data tends to be impressionistic and confined by the context. Archaeology can provide the historian with more precise data on the fundamentals of these aspects of history, resulting thereby in a better comprehension of the early forms of socio‐economic institutions”. The social and economic conditions of Maharashtra during the early historic period have been reconstructed mostly based on available sources like inscriptions, coins and travelers’ accounts. -

Objectives the Main Objective of This Course Is to Introduce Students to Archaeology and the Methods Used by Archaeologists

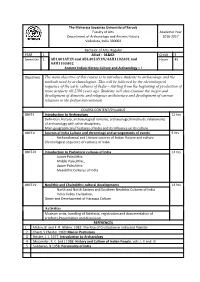

The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Faculty of Arts Academic Year Department of Archaeology and Ancient History 2016-2017 Vadodara, India 390002 Bachelor of Arts: Regular YEAR 1 Allied - 01&02: Credit 3 Semester 1 AB1A01AY1N and AB1A02AY1N/AAH1102A01 and Hours 45 AAH1103A02 Ancient Indian History Culture and Archaeology – I Objectives The main objective of this course is to introduce students to archaeology and the methods used by archaeologists. This will be followed by the chronological sequence of the early cultures of India – starting from the beginning of production of stone artifacts till 2700 years ago. Students will also examine the origin and development of domestic and religious architecture and development of various religions in the Indian subcontinent COURSE CONTENT/SYLLABUS UNIT-I Introduction to Archaeology 12 hrs Definition, history, archaeological remains, archaeological methods, relationship of archaeology with other disciplines; Main geographical of features of India and its influence on its culture UNIT-II Sources of India Culture and chronology and arrangements of events 5 hrs Archaeological and Literary sources of Indian History and culture Chronological sequence of cultures of India UNIT-III Introduction to Prehistoric cultures of India 14 hrs Lower Paleolithic, Middle Paleolithic, Upper Paleolithic, Mesolithic Cultures of India UNIT-IV Neolithic and Chalcolithic cultural developments 14 hrs North and North Eastern and Southern Neolithic Cultures of India Indus Valley Civilization, Origin and Development of Harappa Culture Activities Museum visits, handling of Artefacts, registration and documentation of artefacts,Presentation and discussion REFERENCES 1 Allchin, B. and F. R. Allchin. 1982. The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. -

Autochthonous Aryans? the Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts

Michael Witzel Harvard University Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts. INTRODUCTION §1. Terminology § 2. Texts § 3. Dates §4. Indo-Aryans in the RV §5. Irano-Aryans in the Avesta §6. The Indo-Iranians §7. An ''Aryan'' Race? §8. Immigration §9. Remembrance of immigration §10. Linguistic and cultural acculturation THE AUTOCHTHONOUS ARYAN THEORY § 11. The ''Aryan Invasion'' and the "Out of India" theories LANGUAGE §12. Vedic, Iranian and Indo-European §13. Absence of Indian influences in Indo-Iranian §14. Date of Indo-Aryan innovations §15. Absence of retroflexes in Iranian §16. Absence of 'Indian' words in Iranian §17. Indo-European words in Indo-Iranian; Indo-European archaisms vs. Indian innovations §18. Absence of Indian influence in Mitanni Indo-Aryan Summary: Linguistics CHRONOLOGY §19. Lack of agreement of the autochthonous theory with the historical evidence: dating of kings and teachers ARCHAEOLOGY __________________________________________ Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7-3 (EJVS) 2001(1-115) Autochthonous Aryans? 2 §20. Archaeology and texts §21. RV and the Indus civilization: horses and chariots §22. Absence of towns in the RV §23. Absence of wheat and rice in the RV §24. RV class society and the Indus civilization §25. The Sarasvatī and dating of the RV and the Bråhmaas §26. Harappan fire rituals? §27. Cultural continuity: pottery and the Indus script VEDIC TEXTS AND SCIENCE §28. The ''astronomical code of the RV'' §29. Astronomy: the equinoxes in ŚB §30. Astronomy: Jyotia Vedåga and the -

Iron & Steel Archives

Laval University From the SelectedWorks of Fathi Habashi June, 2018 Iron & steel archives Fathi Habashi Available at: https://works.bepress.com/fathi_habashi/379/ Iron and Steel. Archives and Historians Fathi Habashi Department of Mining, Metallurgical, and Materials Engineering Laval University, Quebec City, Canada [email protected] ABSTRACT The Hittites in Asia Minor are known to be the first to produce iron. The first ferrous material known from ancient times was the iron pillar of Delhi in the 4th century AD. In the Roman Empire iron was produced at Noricum the ancient name for southern Austria. Damascus steel became known at the time of Crusades in the 12th century. Understanding the nature of steel was the aim of many researchers of the 18th and 19th centuries when another mysterious ferrous material became available: iron meteorites. The role of Torbern Bergman in Uppsala in 1781 opened the way to understanding the nature of steel. Books were written afterwards on steelmaking by researchers and educators in Germany, Russia, USA, and England. The Eisen Bibliothek in Switzerland has a collection of iron and steel books. INTRODUCTION Although important books on nonferrous metallurgy were written in the 16th century by Georgius Agricola (1494-1555) and others yet those on ferrous metallurgy started more than a century and half later. There is no explanation for this fact except that the nature of steel and the role of carbon in iron were not known till the work of Torbern Bergman (1735-1784) in Uppsala in 1781. It is believed that iron was first produced by the Hittites in Anatolia around 2000 BC since then it became known all over the world. -

Indian Serpent Lore Or the Nagas in Hindu Legend And

D.G.A. 79 9 INDIAN SERPENT-LOEE OR THE NAGAS IN HINDU LEGEND AND ART INDIAN SERPENT-LORE OR THE NAGAS IN HINDU LEGEND AND ART BY J. PH. A'OGEL, Ph.D., Profetsor of Sanskrit and Indian Archirology in /he Unircrsity of Leyden, Holland, ARTHUR PROBSTHAIN 41 GREAT RUSSELL STREET, LONDON, W.C. 1926 cr," 1<A{. '. ,u -.Aw i f\0 <r/ 1^ . ^ S cf! .D.I2^09S< C- w ^ PRINTED BY STEPHEN AUSTIN & SONS, LTD., FORE STREET, HERTFORD. f V 0 TO MY FRIEND AND TEACHER, C. C. UHLENBECK, THIS VOLUME IS DEDICATED. PEEFACE TT is with grateful acknowledgment that I dedicate this volume to my friend and colleague. Professor C. C. Uhlenbeck, Ph.D., who, as my guru at the University of Amsterdam, was the first to introduce me to a knowledge of the mysterious Naga world as revealed in the archaic prose of the Paushyaparvan. In the summer of the year 1901 a visit to the Kulu valley brought me face to face with people who still pay reverence to those very serpent-demons known from early Indian literature. In the course of my subsequent wanderings through the Western Himalayas, which in their remote valleys have preserved so many ancient beliefs and customs, I had ample opportunity for collecting information regarding the worship of the Nagas, as it survives up to the present day. Other nations have known or still practise this form of animal worship. But it would be difficult to quote another instance in which it takes such a prominent place in literature folk-lore, and art, as it does in India. -

Department of History & Culture

Department of History & Culture CBCE, SEC AND AEC COURSES OFFERED TO B.A. PROGRAMME STUDENTS UNDER CBCS SCHEME Semester Paper No. and Title Nature Credits Semester I Medieval Indian Culture CBCE 4 Semester II A Study of Heritage: Monuments of Delhi (Sultanate Period) SEC 4 Semester III History of Modern China: Eighteemth to Twemtieth Century AEC 4 Semester IV History of USA from Pre Columbian Times to The Cold War CBCE 4 Semester V Political Institutions and Economy in Medieval India CBCE 4 Semester VI History of Russia and USSR (1861-1991) CBCE 4 PROGRAMME: COURSE ID: B.A. Programme BHSX 11P MEDIEVAL INDIAN CULTURE SEMESTER: CREDITS: I 04 Unit-I Kingship and Courtly Cultures 1. Traditions of kingship during the Chola, Sultanate, Vijayanagar and Mughal periods 2. Popular Perceptions of Kingship during Vijayanagar and Mughal periods 3. Courtly cultures and ceremonies: Sultanate, Mughals and Vijayanagar Unit-II Art and Architecture 4. Architectural developments during the Chola, Sultanate, Vijayanagar and Mughal periods 5. Mughal and Rajput paintings 6. Music, musicians and their patrons Unit-III Languages and Literature 7. Growth of Regional Languages and literature 8. Indo-Persian Literature 9. Literary cultures and cultural representations in medieval court Unit-IV Religion and Ideas 10. Growth of Sufism and Sufi silsilas 11. Growth and dissemination of Bhakti-based movements 12. Intellectual trends Suggested Readings: 1. Amrit Rai, A House Divided: The Origin and Development of Hindi/Hindavi, Oxford University Press, Delhi, 1984. 2. Aziz Ahmad, Intellectual History of Islam in India, Edinburg University Press, Edinburg, 1996. 3. Aziz Ahmad, Studies in Islamic Culture in the Indian Environment, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1966. -

Iron Technology and Social Change in Early India (350 B.C.-200 B.C.)

B 2001 NML Jamshedpur 831 007, India; Metallurgy in India: A Retrospective; (ISBN: 81-87053-S6-7); Eds: P. Ramachandra Rao and N.G. Goswami; pp. 134-142. 6 Iron Technology and Social Change in Early India (350 B.C.-200 B.C.) V.K. Thakur Professor of History, Patna University, Patna, India. ABSTRACT The paper encompasses the social changes that have been encountered with the development of iron technology during:350 BC to 200 BC. A greater exploitation of iron mines fulfilled the growing demands for the metals on one side and subsequent technological advancement on the other side. All these have social implication too. Archaelogical evidences also support them. Key words Iron technology, Social change, Ashokan inscription, • Archaclogy. The study of iron in early India, both in its technical and social manifestations, suffers from a serious limitation. Most of the available writings are essentially unidimensional in approach. The society as a prime technological variable gets ignored with the result that social complex is always at the receiving .end, almost as hapless passive formation devoid of any dynamism of its own. Such an under standing of the social role of technology sees techniques as independent of the milieu in which these evolve. This tantamounts to taking a position divorcing the process of the origin and growth of a technology from the contemporaiy .social system, a- line of argument that can lead to funny conclusions. It has to be emphasized, therefore, that the study of technology must keep in mina. the dependent social climate. It is common knowledge that a technological innovation is the product of a social system and, in turn, it becomes viable only when the society gets ready for it. -

Department of Ancient History, Culture and Archaeology University of Allahabad C.B.C.S

Department of Ancient History, Culture and Archaeology University of Allahabad C.B.C.S. ---2016-2016 CBCS Syllabus COURSE STRUCTURE WITH MARKS DISTRIBUTION MONSOON (SPRING ) SEMESTER Course Code Paper/Course M.A.Semester -I Maximum Marks ANC -50 1 Core Paper I: Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture (Political, Social and 60 Marks Economic Institutions) ANC -50 2 Core Paper II : Political History of Ancient India (from 6 th Century B.C. to 60 Marks C. 185 B.C.) ANC -50 3 Core Paper III : Indian Paleography 60 Marks ANC -50 4 Paper IV (a) : Archaeological Theories ( Archaeology Group ) Elective OROROR 60 Marks ANC-505 Paper IV (b): Elements of Indian Archaeology: Prehistory ( Non- Archaeology Group ) Sessional Test/Exam (Semester(Semester----I)I)I)I) Sessional Test/Exam (40 Marks) Exam Schedule Test -1* Third week of September 20 Marks Mid -Semester Exam Third week of October 20 Marks Test -2 * Third week of November 20 Marks *Best of the two test’s marks (Test-1 Or Test-2) will be posted End Semester First /Second Week of December 60 Marks Semester –I: Total Max imum Marks 400 Marks COURSE STRUCTURE WITH MARKS DISTRIBUTION WINTER (AUTUMN ) SEMESTER Course Code Paper/Course M.A.Semester -II Maximum Marks ANC -50 6 Core Paper V : Aspects of Ancient Indian Culture (Religion, Philosophy, 60 Marks Literature and Art) ANC -50 7 Core Paper VI : Political History of Ancient India (from C. 185 B.C. to 319 60 Marks A.D.) ANC -50 8 Core Paper VII : Indian Numismatics 60 Marks ANC -509 Paper VIII (a) : Archaeological Methods and Techniques (Archaeology Group ) Elective OROROR 60 Marks ANC-510 Paper VIII (b): Elements of Indian Archaeology: Protohistory and Historical Archaeology ( Non-Archaeology Group ) Sessional Test/Exam (Semester(Semester----II)II)II)II) Sessional Test/Exam (40 Marks) Exam Schedule Test -1* Third week of January 20 Marks Mid -Semester Exam Last week of February 20 Marks Test -2* Third week of March 20 Marks *Best of the two test’s marks (Test-1 Or Test-2) will be posted End Semester Third week of April 60 Marks Semester –II: Total Maximum Marks 400 Marks 1.