History of India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Configurations of the Indic States System

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 34 Number 34 Spring 1996 Article 6 4-1-1996 Configurations of the Indic States System David Wilkinson University of California, Los Angeles Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Wilkinson, David (1996) "Configurations of the Indic States System," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 34 : No. 34 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol34/iss34/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Wilkinson: Configurations of the Indic States System 63 CONFIGURATIONS OF THE INDIC STATES SYSTEM David Wilkinson In his essay "De systematibus civitatum," Martin Wight sought to clari- fy Pufendorfs concept of states-systems, and in doing so "to formulate some of the questions or propositions which a comparative study of states-systems would examine." (1977:22) "States system" is variously defined, with variation especially as to the degrees of common purpose, unity of action, and mutually recognized legitima- cy thought to be properly entailed by that concept. As cited by Wight (1977:21-23), Heeren's concept is federal, Pufendorfs confederal, Wight's own one rather of mutuality of recognized legitimate independence. Montague Bernard's minimal definition—"a group of states having relations more or less permanent with one another"—begs no questions, and is adopted in this article. Wight's essay poses a rich menu of questions for the comparative study of states systems. -

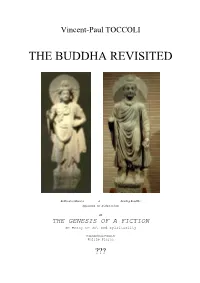

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

What the Romans Knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 • Part II

What the Romans knew Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know • Part II 1 What the Romans knew Archaic Roma Capitolium Forum 2 (Museo della Civiltà Romana, Roma) What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Wars against Carthage resulted in conquest of the Phoenician and Greek civilizations – Greek pantheon (Zeus=Jupiter, Juno = Hera, Minerva = Athena, Mars= Ares, Mercury = Hermes, Hercules = Heracles, Venus = Aphrodite,…) – Greek city plan (agora/forum, temples, theater, stadium/circus) – Beginning of Roman literature: the translation and adaptation of Greek epic and dramatic poetry (240 BC) – Beginning of Roman philosophy: adoption of Greek schools of philosophy (155 BC) – Roman sculpture: Greek sculpture 3 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Greeks: knowing over doing – Romans: doing over knowing (never translated Aristotle in Latin) – “The day will come when posterity will be amazed that we remained ignorant of things that will to them seem so plain” (Seneca, 1st c AD) – Impoverished mythology – Indifference to metaphysics – Pragmatic/social religion (expressing devotion to the state) 4 What the Romans Knew • Greek! – Western civilization = the combined effect of Greece's construction of a new culture and Rome's destruction of all other cultures. 5 What the Romans Knew • The Mediterranean Sea (Mare Nostrum) – Rome was mainly a sea power, an Etruscan legacy – Battle of Actium (31 BC) created the “mare nostrum”, a peaceful, safe sea for trade and communication – Disappearance of piracy – Sea routes were used by merchants, soldiers, -

Art. I.—The Iron Pillar of Delhi

JOURNAL THE ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY. ART. I.— The Iron Pillar of Delhi (Mihrauli) and the Emperor Candra {Chandra). By VINCENT A. SMITH, M.R.A.S., Indian Civil Service. PREFATORY NOTE. THE project of writing the "Ancient History of Northern India from the Monuments" has long occupied my thoughts, but the duties of my office do not permit me, so long as I remain in active service, to devote the time and attention necessary for the execution and completion of so arduous an undertaking. There is, indeed, little prospect that my project will ever be fully carried into effect by me. Be that as it may, I have made some small progress in the collection of materials, and have been compelled from time to time to make detailed preparatory studies of special subjects. I propose to publish these studies occasionally under the general title of " Prolegomena to Ancient Indian History." The essay now presented as No. I of the series is that which happens to be the first ready. It grew out of a footnote to the draft of a chapter on the history of Candra Gupta II. V. A. SMITH, Gorakhpur, India. July, 1896. , J.K.A.S. 1897. x 1 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. INSEAD, on 14 Sep 2018 at 15:56:13, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0035869X00024205 2 THE IRON PILLAR OF DELHI. The great mosque built by Qutb-ud-din 'Ibak in 1191 A.D., and subsequently enlarged by his successors, as well as its minaret, the celebrated Qutb Mlnar, stand on the site of Hindu temples, and within the limits of the fortifications known as the Fort of Rai Pithaura, which were erected in the middle or latter part of the twelfth century to protect the Hindu city of Delhi from the attacks of the Musalmans, who finally captured it in A.D. -

The Heritage of India Series

THE HERITAGE OF INDIA SERIES T The Right Reverend V. S. AZARIAH, t [ of Dornakal. E-J-J j Bishop I J. N. FARQUHAR, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon.). Already published. The Heart of Buddhism. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A. Asoka. J. M. MACPHAIL, M.A., M.D. Indian Painting. PRINCIPAL PERCY BROWN, Calcutta. Kanarese Literature, 2nd ed. E. P. RICE, B.A. The Samkhya System. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. Psalms of Maratha Saints. NICOL MACNICOL, M.A., D.Litt. A History of Hindi Literature. F. E. KEAY, M.A., D.Litt. The Karma-MImamsa. A. BERRIEDALE KEITH, D.C.L., D.Litt. Hymns of the Tamil Saivite Saints. F. KINGSBURY, B.A., and G. E. PHILLIPS, M.A. Rabindranath Tagore. E. J. THOMPSON, B.A., M.C. Hymns from the Rigveda. A. A. MACDONELL, M.A., Ph.D., Hon. LL.D. Gotama Buddha. K. J. SAUNDERS, M.A. Subjects proposed and volumes under Preparation. SANSKRIT AND PALI LITERATURE. Anthology of Mahayana Literature. Selections from the Upanishads. Scenes from the Ramayana. Selections from the Mahabharata. THE PHILOSOPHIES. An Introduction to Hindu Philosophy. J. N FARQUHAR and PRINCIPAL JOHN MCKENZIE, Bombay. The Philosophy of the Upanishads. Sankara's Vedanta. A. K. SHARMA, M.A., Patiala. Ramanuja's Vedanta. The Buddhist System. FINE ART AND MUSIC. Indian Architecture. R. L. EWING, B.A., Madras. Indian Sculpture. Insein, Burma. BIOGRAPHIES OF EMINENT INDIANS. Calcutta. V. SLACK, M.A., Tulsi Das. VERNACULAR LITERATURE. and K. T. PAUL, The Kurral. H. A. POPLBY, B.A., Madras, T> A Calcutta M. of the Alvars. -

Teacher Overview: What Led to the Gupta Golden Age? How Did The

Please Read: We encourage all teachers to modify the materials to meet the needs of their students. To create a version of this document that you can edit: 1. Make sure you are signed into a Google account when you are on the resource. 2. Go to the "File" pull down menu in the upper left hand corner and select "Make a Copy." This will give you a version of the document that you own and can modify. Teacher Overview: What led to the Gupta Golden Age? How did the Gupta Golden Age impact India, other regions, and later periods in history? Unit Essential Question(s): How did classical civilizations gain, consolidate, maintain and lose their power? | Link to Unit Supporting Question(s): ● What led to the Gupta Golden Age? How did the Gupta Golden Age impact India, other regions, and later periods in history? Objective(s): ● Contextualize the Gupta Golden Age. ● Explain the impact of the Gupta Golden Age on India, other regions, and later periods in history. Go directly to student-facing materials! Alignment to State Standards 1. NYS Social Studies Framework: Key Idea Conceptual Understandings Content Specifications 9.3 CLASSICAL CIVILIZATIONS: 9.3c A period of peace, prosperity, and Students will examine the achievements EXPANSION, ACHIEVEMENT, DECLINE: cultural achievements can be designated of Greece, Gupta, Han Dynasty, Maya, Classical civilizations in Eurasia and as a Golden Age. and Rome to determine if the civilizations Mesoamerica employed a variety of experienced a Golden Age. methods to expand and maintain control over vast territories. They developed lasting cultural achievements. -

The Madras Presidency, with Mysore, Coorg and the Associated States

: TheMADRAS PRESIDENG 'ff^^^^I^t p WithMysore, CooRGAND the Associated States byB. THURSTON -...—.— .^ — finr i Tin- PROVINCIAL GEOGRAPHIES Of IN QJofttell HttinerHitg Blibracg CHARLES WILLIAM WASON COLLECTION CHINA AND THE CHINESE THE GIFT OF CHARLES WILLIAM WASON CLASS OF 1876 1918 Digitized by Microsoft® Cornell University Library DS 485.M27T54 The Madras presidencypresidenc; with MysorMysore, Coor iliiiiliiiiiiilii 3 1924 021 471 002 Digitized by Microsoft® This book was digitized by Microsoft Corporation in cooperation witli Cornell University Libraries, 2007. You may use and print this copy in limited quantity for your personal purposes, but may not distribute or provide access to it (or modified or partial versions of it) for revenue-generating or other commercial purposes. Digitized by Microsoft® Provincial Geographies of India General Editor Sir T. H. HOLLAND, K.C.LE., D.Sc, F.R.S. THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES Digitized by Microsoft® CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS HonBnn: FETTER LANE, E.G. C. F. CLAY, Man^gek (EBiniurBi) : loo, PRINCES STREET Berlin: A. ASHER AND CO. Ji-tipjifl: F. A. BROCKHAUS i^cto Sotfe: G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS iBomlaj sriB Calcutta: MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. All rights reserved Digitized by Microsoft® THE MADRAS PRESIDENCY WITH MYSORE, COORG AND THE ASSOCIATED STATES BY EDGAR THURSTON, CLE. SOMETIME SUPERINTENDENT OF THE MADRAS GOVERNMENT MUSEUM Cambridge : at the University Press 1913 Digitized by Microsoft® ffiambttige: PRINTED BY JOHN CLAY, M.A. AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS. Digitized by Microsoft® EDITOR'S PREFACE "HE casual visitor to India, who limits his observations I of the country to the all-too-short cool season, is so impressed by the contrast between Indian life and that with which he has been previously acquainted that he seldom realises the great local diversity of language and ethnology. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College Is

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE IS GANGAIKONDA CHOLAPURAM BUILT BASED ON VAASTU SASTRA? A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE By Ramya Palani Norman, Oklahoma 2019 IS GANGAIKONDA CHOLAPURAM BUILT BASED ON VAASTU SASTRA? A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE CHRISTOPHER C. GIBBS COLLEGE OF ARCHITECTURE BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Callahan, Marjorie P., Chair Warnken, Charles G. Fithian, Lee A. ©Copyright by RAMYA PALANI 2019 All Rights Reserved. iv Abstract The Cholas (848 CE – 1279 CE) established an imperial line and united a large portion of what is now South India under their rule. The Cholas, known worldwide for their bronze sculptures, world heritage temples and land reforms, were also able builders. They followed a traditional systematic approach called Vaastu Sastra in building their cities, towns, and villages. In an attempt to discover and reconstruct Gangaikonda Cholapuram, an administrative capital (metropolis) of the Chola Dynasty, evidence is collected from the fragments of living inscriptions, epigraphs, archaeological excavation, secondary sources, and other sources pertinent to Vaastu Sastra. The research combines archival research methodology, archaeological documentation and informal architectural survey. The consolidation, analysis, and manipulation of data helps to uncover the urban infrastructure of Gangaikonda Cholapuram city. Keywords: Chola, Cola, South India, Vaastu Shastra, Gangaikonda Cholapuram, Medieval period, -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

Banbhore) (200 Bc to 200 Ad)

INTERNATIONAL TRADE OF SINDH FROM ITS PORT BARBARICON (BANBHORE) (200 BC TO 200 AD) BY M.H. PANHWAR This period covers the rule of Bactrian Greeks, Scythians, Parthians and Kushans in Sindh, rest of the present Pakistan and parts of India. The origins of the development of European trade in the Sindh and trade routes under notice go back to later part of the sixth century BC, and it involved continuous efforts over next seven centuries. (a) After Darius-I’s conquest of Gandhara and Sindhu, admiral Skylax (a Greek of Caryanda), made exploratory voyage down the Kabul and the Indus from Kaspapyrus or Kasyabapura (Peshawar) to the Sindh coast and thence along the Arabian coast to the Red Sea and Egypt in 518 BC, completing the journey in 2 1/2 years and returning to Iran in 514 BC. The voyage was meant to connect the South Asia with Egypt. Darius-I also restored Necho-II’s canal connecting the Nile with the Red Sea. Thus he made Egypt and not Mesopotamia the main line of communication between the Indian and the Mediterranean Oceans. Darius built ‘the Royal Road’ connecting various cities of the empire. It ran the distance of 1677 well-garrisoned miles from Euphesus to Susa. A much longer route than this was from Babylon to Ecbatans and from thence to Kabul, which was already connected with Peshawar. The great voyage of Skylax connected Peshawar with the Red Sea and Egypt, via the Indus and the Arabian Sea. The earlier Egyptian navigation under Pharaohs had purely utilitarian and limited objectives were in no way similar to the great historical voyages, like one by Skylax, for general exploration. -

Religious Spots Within Forts and Fort Sites

Eurasian Journal of Humanities Vol. 1. Issue 1. (2015) ISSN: 2413-9947 Religious spots within forts and fort sites: a study in cultural history of Bundelkhand region in India Purushottam Singh Vikramajit Singh Sanatan Dharm College Kanpur India [email protected] Abstract Bundelkhand geographically situated in exactly the south of the Ganges plane is memorable due to the ancient references. Firstly, saints, devotees, hermits were attracted from Ganges plane towards the isolated, solitary pleasing zone of Vindhyatavi. (Singh, Rajendra, 1994, pp.1, 2) The history of Bundelkhand starts from the Chedi dynasty. (Singh, Rajendra, 1990, pp.80-85) The two famous cities of that time Shuktimati and Shahgeet are now a matter of research. After Chedis, Gupta rulers and Harsh Vardhan became the main rulers, but Chandelas were the first ruler who constructed with the capital of the region of Chedis. (Majumdar, 1951, p.252) The Bundelas and Marathas can also be regarded in this sense. There was no fort without religious spots. The religious spots in the forts of Bundelkhand were the center of belief not only for royal families but also become the center of faith and reverence of general people. Therefore these sites have gained unique and peerless fame. The religious sites within the forts played an important role in preserving and recharging the cultural heritage up to the centuries in Bundelkhand. These became the cause of cultural and religious harmony between the royal families and general people. These religious centers always released the message of prayer, peace and wish of prosperity from the royal family. Many times these temples and other spots provided the faithful with links between the royal families and general people which resulted to be the cause of welfare rule in the region. -

Revised Study Guide

Spring 2021 Arts of Asia Lecture Series The Power of Images in Asian Art: Making the Invisible Visible Sponsored by the Society for Asian Art THE ENIGMA OF THE SCULPTURES AT KHAJURAHO Mary-Ann Milford-Lutzker, Carver Professor Emerita of East Asian Studies, Mills College January 22, 2021 Candella Dynasty: c. 830-1308 CE Harsha ca. 905-925 Yasovarman 925-950 Dhanga 950-999 Ganda 999-1003 Vidyadhara ca. 1004-1035 1019 and 1022: attacks by Mahmud of Ghazni Terms: alamkara: adornment, ornament, figure of speech apsara: heavenly female dancers mithuna: loving couples slesha: puns and double-entendres sura-sundaras, heavenly females vedibhanda: basement, foundation yantra: an abstract symbol for a field of energy Laksmana (Visnu) Temple, 954 CE inscription of Dhanga (double transcepts, Varaha Shrine, panchayatana design, 4 subsidiary shrines) Inscription dated 953-954 in the reign of Dhanga tells us that the temple was constructed by the Chandella King Yasovarman who died before 954, therefore, it was constructed between 930-950 and dedicated for worship in 953/4. Dedicated to the Vaikuntha form of Visnu, distinguished by 3 heads: lion, man and boar Vishvanath (Siva) Temple, late 10th C. Inscription by King Dhanga, 999 CE, refers to two lingas, an emerald and a stone one panchayatana design (main temple and 4 shrines) Kandariya Mahadeva (Siva) Temple, 1025-50 CE erected by Vidyadhara? Inscription refers to King Virimda, perhaps a name of King Vidhyadara Prabodhachandrodaya (Moonrise of Pure Knowledge) an allegorical play by Krishna Misra References: Dehejia, Vidya, The Body Adorned. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009. Desai, Devangana, Erotic Sculpture of India: A Socio-Cultural Study.