Malaysian English – a Distinct Variety

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discover the Taste of Solo

Discover the Taste of Solo Sejak tahun 1988, Dapur Solo berdedikasi untuk melestarikan kuliner tradisional Jawa. Dapur Solo dikenal akan keahliannya dalam kreasi hidangan khas Jawa untuk masyarakat modern, tanpa meninggalkan nilai unik dan tradisional. Seluruh sajian dimasak dengan penuh perhatian akan keunggulan dan keasliannya. KHAS SOLO 01 01. Nasi Urap Solo 40,5 Nasi, sayuran urapan dengan rasa sedikit pedas, pilihan lauk ayam / empal goreng, tempe bacem Dengan nasi kuning +1.000 02. Nasi Langgi Solo 41,5 Nasi langgi kuning khas Solo yang disajikan dengan ayam / empal goreng, terik daging, sambal goreng kentang, abon sapi, telur dadar tipis, serundeng kelapa, kering kentang, lalap serta kerupuk udang dan sambal Dengan nasi putih 40.500 02 04 03. Nasi Langgi Si Kecil 30,5 Nasi kuning dengan pilihan ayam goreng, abon sapi, telur dadar tipis dan kerupuk udang 04. Nasi Liwet Solo 40,5 Nasi gurih dengan suwiran ayam kampung, telur pindang, tempe bacem dan potongan ati ampela ayam disiram dengan sayur labu dengan rasa gurih sedikit pedas Menu favorit Menu pilihan anak 05 06 05. Lontong Solo 40,8 Lontong yang disiram dengan kuah opor kuning lengkap dengan suwiran ayam, telur pindang dan sambal goreng kentang 06. Timlo Solo 37,5 Sop kuah bening berisi sosis Solo, suwiran ayam, dan telur pindang 07. Selat Solo 41 Perpaduan daging semur yang manis dan mustard yang asam serta sayuran, menghasilkan cita rasa perpaduan dua budaya Jawa dan Belanda 07 Menu favorit Menu pilihan anak NUSANTARA 01 01. Nasi Timbel Sunda 42 Nasi timbel dengan pilihan lauk ayam / empal goreng, sayur asem, ikan asin, tempe bacem serta disajikan dengan kerupuk udang, lalap dan sambal 02 02. -

Depot Podjok Menu 2020 Nederlands 20200806.Indd

Bijgerechten (per 100 gram) Snacks Udang Peté € 7,50 Pangsit € 6,50 Gepelde kleine garnalen met Peteh bonen 6 stuks krokant gebakken Indonesische wontons met kip depot podjok Udang rica € 6,00 Loempia semarang € 2,75 Gepelde garnalen in pitti ge saus Loempia gevuld met jonge bamboe en kip Rendang € 3,50 Soempia € 2,50 INDONESISCH EETHUIS Langzaam gegaard pitti g rundvlees 6 stuks vegetarische mini loempia’s & CATERING Smoor € 3,00 Loempia ayam € 2,50 Rundvlees gesmoord in zoete saus Loempia gevuld met kip en groenten Tumis boontjes € 2,50 Panada € 2,50 Gewokte boontjes Pastei gevuld met tonijn Sayur lodeh € 3,00 Bapao € 2,50 Groenten in kokosbouillon Gestoomd broodje gevuld met kip of rund Orak arik € 2,75 Lemper € 2,50 Gewokte groenten Kleefrijst gekookt in kokos gevuld met gekruide kip Terong balado € 2,75 Pastei ayam € 2,50 Aubergine in pitti ge saus Pastei gevuld met kip en groenten Atjar djawa € 3,50 Risoles ayam € 2,50 Tafelzuur van komkommer en rode ui Krokant gepaneerd fl ensje gevuld met kipragout Dadar gulung € 2,50 Bijgerechten (per portie) Indonesische pannenkoek gevuld met kokos en palmsuiker Dadar isi € 8,50 Gevulde omelet met rundergehakt Sponscake € 2,50 Pandan cake Nasi kuning extra € 6,50 Spekkoek € 2,25 Nasi djawa extra € 6,50 In laagjes gebakken kruidige cake Catering Nasi goreng extra € 5,50 Dranken Iam Super Juice € 3,00 Depot Podjok verzorgt ook catering op maat. Bami goreng extra € 5,50 Diverse frisdranken € 2,75 Voor een afspraak kunt u contact opnemen. Teh botol € 2,00 Wi� e rijst extra € 4,00 Bintang € 3,50 Adres -

Singapore Dishes TABLE of CONTENTS

RECIPE BOOKLET ERIC M A’ A S C O D O N K A E R B R Singapore Dishes TABLE OF CONTENTS COOKING WITH PRESSURE ................................................. 3 VENTING METHODS ................................................................ 4 INSTANT POT FUNCTIONS COOKING TIME ................... 5 MAINS HAINANESE CHICKEN RICE .................................................. 6 STEAMED SHRIMP GLASS VERMICELLI .......................... 8 MUSHROOM & SCALLOP RISOTTO ................................... 10 CHICKEN VEGGIE MAC AND CHEESE............................... 12 HAINANESE HERBAL MUTTON SOUP.............................. 14 STICKY RICE DUMPLINGS ..................................................... 16 CURRY CHICKEN ....................................................................... 18 TEOCHEW BRAISED DUCK ................................................... 19 CHICKEN CENTURY EGG CONGEE .................................... 21 DESSERTS PULOT HITAM ............................................................................ 22 STEAMED SUGEE CAKE ........................................................ 23 PANDAN CAKE........................................................................... 25 Cooking with Pressure FAST The contents of the pressure cooker cooks at a higher temperature than what can be achieved by a conventional Add boil — more heat means more speed. ingredients Pressure cooking is about twice as fast as conventional cooking (sometimes, faster!) & liquid to Instant Pot® HEALTHY Pressure cooking is one of the healthiest -

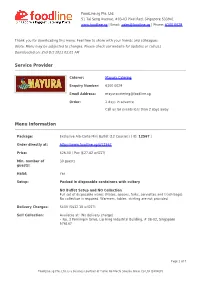

Service Provider Menu Information

FoodLine.sg Pte. Ltd. 51 Tai Seng Avenue, #03-03 Pixel Red, Singapore 533941 www.foodline.sg | Email: [email protected] | Phone: 6100 0029 Thank you for downloading this menu. Feel free to share with your friends and colleagues. (Note: Menu may be subjected to changes. Please check our website for updates or call us.) Downloaded on: 2nd Oct 2021 02:01 AM Service Provider Caterer: Mayura Catering Enquiry Number: 6100 0029 Email Address: [email protected] Order: 2 days in advance Call us for events less than 2 days away Menu Information Package: Exclusive Ala-Carte Mini Buffet (12 Courses) ( ID: 12567 ) Order directly at: https://www.foodline.sg/d/12567 Price: $26.00 / Pax ($27.82 w/GST) Min. number of 30 guests guests: Halal: Yes Setup: Packed in disposable containers with cultery NO Buffet Setup and NO Collection Full set of disposable wares (Plates, spoons, forks, serviettes and trash bags). No collection is required. Warmers, tables, skirting are not provided. Delivery Charges: S$30 (S$32.10 w/GST) Self Collection: Available at: (No delivery charge) • No. 3 Pemimpin Drive, Lip Hing Industrial Building, # 08-02, Singapore 576147 Page 1 of 7 FoodLine.sg Pte. Ltd. is a business partner of Yume No Machi Souzou Iinkai Co Ltd (2484:JP) FoodLine.sg Pte. Ltd. 51 Tai Seng Avenue, #03-03 Pixel Red, Singapore 533941 www.foodline.sg | Email: [email protected] | Phone: 6100 0029 Terms and Actual delivery timing may vary +/- 30 mins from the stipulated delivery time Conditions: due to unforeseen circumstances such as weather and traffic condition. -

Mek Mulung Di Pentas Dunia Pentas Di Mulung Mek

ISSN 2180 - 009 X Bil 1/2015 NASKHAH PERCUMA Assalamualaikum dan Salam 1Malaysia Lafaz syukur seawal bicara yang dapat diungkapkan atas penerbitan buletin JKKN Bil 1/2015 yang kini dikenali sebagai “Citra Seni Budaya”. Penjenamaan semula buletin ini adalah bertitik tolak daripada hasrat dan usaha JKKN untuk melaksanakan transformasi bagi memastikan setiap program dan aktiviti yang dilaksanakan memberi impak positif kepada masyarakat di samping pulangan kepada peningkatan ekonomi negara. Merujuk kepada Kamus Dewan Edisi Ke-4, Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, perkataan “Citra” membawa maksud ‘gambaran’ atau ‘imej peribadi seseorang’. Oleh itu, “Citra Seni Budaya” adalah refleksi kepada usaha murni JKKN yang dilaksanakan secara berterusan untuk memartabatkan seni dan budaya. Ia akan menjadi wadah perkongsian ilmu serta maklumat mengenai seni dan budaya yang boleh dimanfaatkan sebagai salah satu sumber rujukan sampingan. Semoga usaha kecil ini boleh membantu merealisasikan hasrat JKKN bagi menyebarluaskan maklumat berkaitan seni budaya yang hakikatnya berada bersama kita saban hari. Salmiyah Ahmad CORETAN EDITOR CORETAN Editor JABATAN SIDANG KEBUDAYAAN DAN EDITORIAL KESENIAN NEGARA YBhg. Datuk Norliza Rofli • Muhammad Faizal Ruslee Ketua Pengarah • Siti Anisah Abdul Rahman • Fauziah Ahmad YBrs. En. Mohamad Razy Mohd Nor Timbalan Ketua Pengarah Pereka Grafik/Kreatif (Sektor Dasar dan Perancangan) Bafti Hera Abu Bakar YBrs. Tn. Hj. Mesran Mohd Yusop Jurufoto Timbalan Ketua Pengarah Zaman Sulieman (Sektor Kebudayaan dan Kesenian) SIDANG REDAKSI YBrs. -

Kuaghjpteresalacartemenu.Pdf

Thoughtfully Sourced Carefully Served At Hyatt, we want to meet the needs of the present generation without compromising what’s best for future generations. We have a responsibility to ensure that every one of our dishes is thoughtfully sourced and carefully served. Look out for this symbol on responsibly sourced seafood certified by either MSC, ASC, BAP or WWF. “Sustainable” - Pertaining to a system that maintains its own viability by using techniques that allow for continual reuse. This is a lifestyle that will inevitably inspire change in the way we eat and every choice we make. Empower yourself and others to make the right choices. KAYA & BUTTER TOAST appetiser & soup V Tauhu sambal kicap 24 Cucumber, sprout, carrot, sweet turnip, chili soy sauce Rojak buah 25 Vegetable, fruit, shrimp paste, peanut, sesame seeds S Popiah 25 Fresh spring roll, braised turnip, prawn, boiled egg, peanut Herbal double-boiled Chinese soup 32 Chicken, wolfberry, ginseng, dried yam Sup ekor 38 Malay-style oxtail soup, potato, carrot toasties & sandwich S Kaya & butter toast 23 White toast, kaya jam, butter Paneer toastie 35 Onion, tomato, mayo, lettuce, sour dough bread S Roti John JP teres 36 Milk bread, egg, chicken, chili sauce, shallot, coriander, garlic JPt chicken tikka sandwich 35 Onion, tomato, mayo, lettuce, egg JPt Black Angus beef burger 68 Coleslaw, tomato, onion, cheese, lettuce S Signature dish V Vegetarian Prices quoted are in MYR and inclusive of 10% service charge and 6% service tax. noodles S Curry laksa 53 Yellow noodle, tofu, shrimp, -

INFUSION CAFÉ RESTAURANT BUFFET HITEA 1 Cold Cuts

INFUSION CAFÉ RESTAURANT BUFFET HITEA 1 Cold cuts (e.g – Beef salami, Roasted Beef, Meatloaf, Chicken Meatloaf, Mortadella, Beef Pepperoni, Beef Pastrami, Chicken Lyoner, Roasted Chicken) Organic Plain Salads Station Baby Spinach, Lettuce Iceburg, Asparagus , Baby Cucumber, Beetroot, Brocolli, Carrot, Cauliflower, Cherry Tomatoes, Butterhead, Wild Rocket, Mix garden salad ,Traffic Light Capsicum and Baby Romaine Lettuce with condiment and dressing Combine Salads (local & western) Chef creation and ideas 4 type. e.g- ETC……………………….. Thai Seafood Sld with Caremelized Pumpkin, Marinated Artichoke and Raddichio with Cottage Cheese, Boiled Prawns with Mango Salsa and curry Vinaigrette, Roasted Champignon ,Chestnut and Celery sld, Grilled Fennel with Orange sld, Poached Chicken Roulade with mixed fruits salad, Marinated Seared Tuna with Avocado,Tomoatoes and Asparagus Malaysian Local Bites Ulam Ulaman kampong with Cincaluk,Sambal Belacan in the basket 3 types of Local crackers 2 types of Salted Fish Local Counter - Rojak Of the Day Counter - (1 types) e.g – Gado – gado Indonesia , Rojak Buah Buahan, Indian Rojak with Spicy Indian Sauce, Rojak Pasemboh, Pecal Johor, Rojak Petis Johor, Rojak Tahu, Timun dan sambal Kicap.Tahu Sumbat w sc Dressing and Dipping Homemade Raspberry Vinaigrette,Homemade Orange Vinaigrette, Homemade Kiwi Vinaigrette, Lemon Vinaigrette, Thousand Island,French Dressing,Vinaigrette Dressing,Creamy French Dressing,Caesar dressing and Blue cheese. Assorted Japanese and Local Sushi- ala min prepare (e.g - Inari Sushi, Chuka Itaki Sushi, Chuka Hotite Sushi, Salmon Sushi, Kani Inari Sushi, Tuna Sushi, Ebiko Sushi, Samon Mayo Sushi, Aburi Cheese Sushi, Abalone Sushi, Chuka Jellyfish Sushi and Chuka Wabame) With Homemade Wasabi,Soyu and Tepanyaki sauce,Homemade Pickle Ginger Special Chinese Cooking Section - Ala Minute Fried Noodles any style with Yellow Mee,Mee Hoon and Kway Teow Chinese Styles . -

Dinner Buffet Malaysia Appetizer Ulam-Ulaman ,Sotong Kangkong

Dinner Buffet Malaysia Appetizer Ulam-ulaman ,sotong kangkong,rojak petis ,temper jawa, kerabu daging,kerabu taugeh,kerabu manga, kerabu soon,kerabu betik,acar mentah , kerabu kacang panjang ,kerabu sotong,kerabu telur dan kerabu ayam acar buah,telur masin,ikan masin goreng,malaysian crackers, jelatah, acar rampai & pickles sambal belacan, chutney, cincaluk, budu,sambal kicap Salad Farm 7 type of assorted garden salad tomato, cucumber, onion ring, carrot, serves with 1000 island dressing, Italian dressing & French dressing Sup Area Soto ayam with condiment Served with freshly baked homemade bread loafs, rolls and baguettes with butter. In the Glass Vegetable Tempura Served with wasabi and ginger soyu sauce Asian Pizza In The Box 2 type Malay pizza with nasi lemak & satay flavour Sauna Glass Roti jala ,putu mayam, lemang Served with vegetarian curry, sugar cane & coconut Live stall Char counter Served with 4 type of noodle, 6 type of vegetable and 3 type of meat. Noodle Stall 1 Laksa Serawak Boil egg, onion slice, fried onion, spring onion, red chilli, cucumber, bean sprout, lime, prawn meat, slice beef & slice chicken Pasta ala asia Stall Fusion 2 type Asian style pasta kungpow and rendang Carving stall Chicken Percik Served with white rice and percik sauce Rojak Counter Pasembor with condiment. Rojak buah with condiment Charcoal Area Cajun lamb shoulder, honey chicken wing, 2 type of fish, , Otak-otak, Chicken and beef satay serves with peanut sauce and condiment Main fare Nasi tomato ayam masak merah Thai fried mee hoon Butter mix vegetable Kari telur Chilli Crab Daging dendeng Lamb stronganof with potato Kid Street Chocolate fountain, ice mounting, cotton candy, 4 type Ice cream corner, fish finger Dessert area , coconut cream caramel,Assorted slice cake, assorted jelly, assorted sweet pie,Buah kurma,kuih wajid,kuih seri muka,pulut inti kelapa, dodol, kuih bahulu, kuih peneram, kuih makmur,kuih siput, kuih tart nenas, kuih batang buruk, Bubur durian,lin chee kang 4type mix fruit ,4 type local fruit. -

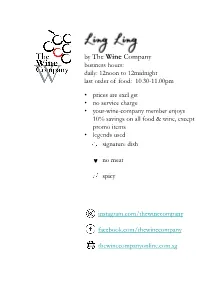

Ling Ling by the Wine Company Page 1 of 19 Nibbles

by The Wine Company business hours: daily: 12noon to 12midnight last order of food: 10.30-11.00pm • prices are excl gst • no service charge • your-wine-company member enjoys 10% savings on all food & wine, except promo items • legends used signature dish no meat spicy instagram.com/thewinecompany facebook.com/thewinecompany thewinecompanyonline.com.sg lunch available from 12pm to 3pm with complimentary coffee or tea or ice lemon tea hot dog 3.90 1 pc of hot dog with mustard; bun is lightly toasted add $1 for egg or avocado or bacon cream of mushroom 5.90 180g, made-from-scratch, assorted mushrooms, blended with cream drizzled with truffle oil; served with sugar cheese bun caesar salad 6.90 130g, a la minute of romaine lettuce, tomatoes, quail eggs, bacon bits, croutons, pine nuts and parmesan cheese pig trotter beehoon 6.90 150g, traditional hokkien comfort food, simple and oh so yummy cantonese porridge 6.90 porridge flavored with bone stock; garnished with spring onion, ginger & fried dough choice of chicken or pork add one century egg or one salted egg for $1.90 curry chicken 6.90 a concoction of singapore and malaysia style curry chicken fragrant steamed rice complimentary from the menu 30% savings select from mains, pasta and desserts price excl gst Ling Ling by The Wine Company page 1 of 19 nibbles fried ikan bilis and peanuts 4.90 130g of local anchovies; delicious and crunchy this is available until closing time recommend to pair with your favourite wine classic papadum 4.90 8pcs of indian-styled wafers served with cucumber-yogurt -

Pandan Gula Melaka Cheese Cake | Bakels Malaysia

www.maybakels.com DISPLAY CONDITIONS Chilled CATEGORY Cakes, Muffins & Sponge Products FINISHED PRODUCT Cake, Cheesecake PANDAN GULA MELAKA CHEESE CAKE www.maybakels.com INGREDIENTS Group A Ingredient KG Bakels Light Cheese Cake Mix 0.300 Dairy Whipping Cream 0.300 Egg Yolk (pcs) 0.150 Water 0.100 Total Weight: 0.850 Group B Ingredient KG Egg White 0.170 Sugar 0.120 Total Weight: 0.290 Group Mousse: Ingredient KG Bakels Mousse Mix 0.100 Water 0.120 Dairy Whipping Cream 0.300 Fresh Grated Coconut 0.200 Total Weight: 0.720 Group Topping: Ingredient KG Coconut Milk 0.200 Butter 0.070 Gula Melaka 0.080 Black Colouring - Total Weight: 0.350 METHOD Method: 1. Whisk Ingredients A on medium speed for 3 minutes, till well combined. 2. Whisk Ingredients B until soft peak. 3. Fold Mixture A into Mixture B. Divide the batter into two parts, first part batter, pour into the lined baking tray 12" x 12", second part batter add a few drops of Bakels Pandan Paste and pour into the second lined baking tray 12" x 12". Bake at 180°C for 15 minutes. 4. Let it cool and cut into 2 pieces of 6"x6" for both cakes. This recipe can make 2 of 6” x 6” cakes. 5. To make mousse: Whip the whipping cream till soft peak, set aside. Mix well mousse mix and water, then add in coconut milk. Fold in whipping cream. Divide the whipping cream into 4 parts. 6. To make Topping: In a saucepan, heat up butter and gula melaka until is melted. -

Souq Dinner Menu 1 APPERTISER Ulam Raja, Selom, Pucuk Pengaga

Souq Dinner Menu 1 APPERTISER Ulam Raja, Selom, Pucuk Pengaga, Kacang Botol Jantung Pisang, Petai, Pucuk Ubi, Timun, Bendi, Sambal Served With Sambal Belacan,Budu, Cencaluk, Tempoyak, Sambal Hitam, Sambal Kicap, Sambal Manga Muda, Sambal Cili Kering, Sambal Kelapa. Kerabu Mangga, Betik, Taugeh, Kerabu Ayam,Kerabu Perut Acar Jelatah, Jeruk, Cermai, Kelubi, Manga, Betik, Jambu, Anggur Rojak Pasembur Dan Rojak Buah HEALTHY GREENS Iceberg Lettuce, Frisee, Red Coral, Green Coral, Red Radicchio Green Capsicum, Red Capsicum, Carrot, Cucumber, Cherry Tomato, Sweet Corn Served With Sesame, Caesar, Italian, Thousand Island and Balsamic Dressing ITALIAN SECTION With Selection Of Spaghetti, Fettuccini And Penne. And Chioces Of Bolognaise, Cabonara, Napolitana Cooked To Perfection With Onion, Pepper, Turkey, Garlic, Mushroom, Parmesan Cheese KIDS ZONE Chicken Nuggets,Mini Pizza,Open Face Burger,Potato Chips Chocolate Fountain With Marshmallow,Fruit Dip All prices quoted in Malaysian Ringgit are inclusive of 10% service charge and 6% service tax Guests with allergies and intolerances should make a member of the team aware, before placing an order for food or beverages. Guests with severe allergies or intolerances, should be aware that although all due care is taken, there is a risk of allergen ingredients still being present. Please note, any bespoke orders requested cannot be guaranteed as entirely allergen free and will be consumed at the guest’s own risk. BARBEQUE ZONE Ikan Bakar Terubuk, Ikan Pari, Cencaru, Keli, Talapia, Dory, Ayam Percik Air Asam,Sambal Kicap,Sambal Belacan,Black Pepper,Bbq Sauce. Satay Ayam Dan Daging, Nasi Himpit, Bawang,Timun Dan Kuah Kacang, Otak Otak Gelang Patah, Lemang, Ketupat Palas, Serunding Ayam, Serunding Daging NOODLES ZONE Assam Laksa, Mee Rebus Haji Wahid Char Kway teaw kerang dan Mee Goreng Mamak SIGNATURE’S ZONE Soup Gearbox dengan Roti Benggali Roasted Whole Lamb with Garden Vegetables and Potatoes Served with Mint Sauce, Black Pepper, And Mushroom Sauce. -

2608 Nicollet Ave. S. Minneapolis, MN 55408

Peninsula, named after the Malay Peninsula, is established by a group of Malaysians with great passion of bringing the most authentic Malaysian and Southeast Asian cuisine to the Twin Cities. We are honored to present you with one of the finest Chefs in Malaysian cuisine in the country to lead Peninsula for your unique dining experience. We sincerely thank you for being our guests. 2608 Nicollet Ave. S. Minneapolis, MN 55408 Tel: 6128718282 Fax: 6128712863 www.PeninsulaMalaysianCuisine.com We open seven days a week. Hours: Sunday – Thursday: 11:00am – 10:00pm Friday & Saturday: 11:00am – 11:00pm Parking: Restaurant Parking in the rear (all day) Across the street at Dai Nam Lot (6pm closed) Valet Parking (Friday & Saturday 6pm – closed) APPETIZERS 开胃小菜 001. ROTI CANAI 印度面包 3.95 All time Malaysian favorite. Crispy Indian style pancake. Served with spicy curry chicken & potato dipping sauce. Pancake only 2.75. 002. ROTI TELUR 面包加蛋 4.95 Crispy Indian style pancake filled with eggs, onions & bell peppers. Served with spicy curry chicken & potato dipping sauce. 003. PASEMBUR 印度罗呀 7.95 Shredded cucumber, jicama, & bean sprout salad topped with shrimp pancakes, sliced eggs, tofu & a sweet & spicy sauce. 004. PENINSULA SATAY CHICKEN 沙爹鸡 6.95 Marinated & perfectly grilled chicken on skewers with homemade spicy peanut dipping sauce. 005. PENINSULA SATAY BEEF 沙爹牛 6.95 Marinated & perfectly grilled beef on skewers with homemade spicy peanut dipping sauce. 006. SATAY TOFU 沙爹豆腐 5.95 Shells of crispy homemade tofu, filled with shredded cucumbers, bean sprouts. Topped with homemade peanut sauce. 007. POPIAH 薄饼 4.95 Malaysian style spring rolls stuffed with jicama, tofu, & bean sprouts in freshly steamed wrappers (2 rolls).