From "Duties of Country"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unification of Italy and Germany

EUROPEAN HISTORY Unit 10 The Unification of Italy and Germany Form 4 Unit 10.1 - The Unification of Italy Revolution in Naples, 1848 Map of Italy before unification. Revolution in Rome, 1848 Flag of the Kingdom of Italy, 1861-1946 1. The Early Phase of the Italian Risorgimento, 1815-1848 The settlements reached in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna had restored Austrian domination over the Italian peninsula but had left Italy completely fragmented in a number of small states. The strongest and most progressive Italian state was the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in north-western Italy. At the Congress of Vienna this state had received the lands of the former Republic of Genoa. This acquisition helped Sardinia-Piedmont expand her merchant fleet and trade centred in the port of Genoa. There were three major obstacles to unity at the time of the Congress of Vienna: The Austrians occupied Lombardy and Venetia in Northern Italy. The Papal States controlled Central Italy. The other Italian states had maintained their independence: the Kingdom of Sardinia, also called Piedmont-Sardinia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (ruler by the Bourbon dynasty) and the Duchies of Tuscany, Parma and Modena (ruled by relatives of the Austrian Habsburgs). During the 1820s the Carbonari secret society tried to organize revolts in Palermo and Naples but with very little success, mainly because the Carbonari did not have the support of the peasants. Then came Giuseppe Mazzini, a patriotic writer who set up a national revolutionary movement known as Young Italy (1831). Mazzini was in favour of a united republic. -

The Unification of Italy

New Dorp High School Social Studies Department AP Global Mr. Hubbs & Mrs. Zoleo The Unification of Italy While nationalism destroyed empires, it also built nations. Italy was one of the countries to form from the territories of the crumbling empires. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Austria ruled the Italian provinces of Venetia and Lombardy in the north, and several small states. In the south, the Spanish Bourbon family ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Nevertheless, between 1815 and 1848, increasing numbers of Italians were no longer content to live under foreign rulers. Amid growing discontent, two leaders appeared—one was idealistic, the other practical. They had different personalities and pursued different goals. But each contributed to the Unification of Italy. The Movement for Unity Begins In 1832, an idealistic 26-year-old Italian named Guiseppe Mazzini organized a nationalist group called, Young Italy. Similarly, youth were the leaders and custodians of the nineteenth century nationalist movements. The Napoleonic Wars were lead principally by younger men. Napoleon was 35 years of age when crowned Emperor. As nationalism spread across Europe the pattern continued. People over 40 were excluded from Mazzini's organization. During the violent year of 1848, revolts broke out in eight states on the Italian Peninsula. Mazzini briefly headed a republican government in Rome. He believed that nation-states were the best hope for social justice, democracy, and peace in Europe. However, the 1848 rebellions failed in Italy as they did elsewhere in Europe. The foreign rulers of the Italian states drove Mazzini and other nationalist leaders into exile. -

Mcq Drill for Practice—Test Yourself (Answer Key at the Last)

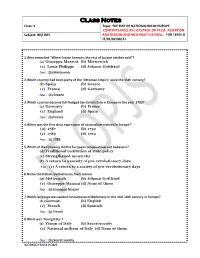

Class Notes Class: X Topic: THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN EUROPE CONTENTS-MCQ ,FILL UPS,TRUE OR FALSE, ASSERTION Subject: HISTORY AND REASON AND MCQ PRACTICE DRILL… FOR TERM-I/ JT/01/02/08/21 1.Who remarked “When France Sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold”? (a) Giuseppe Mazzini (b) Metternich (c) Louis Philippe (d) Johann Gottfried Ans : (b) Metternich 2.Which country had been party of the ‘Ottoman Empire’ since the 15th century? (b) Spain (b) Greece (c) France (d) Germany Ans : (b) Greece 3.Which country became full-fledged territorial state in Europe in the year 1789? (c) Germany (b) France (c) England (d) Spain Ans : (b) France 4.When was the first clear expression of nationalism noticed in Europe? (a) 1787 (b) 1759 (c) 1789 (d) 1769 Ans : (c) 1789 5.Which of the following did the European conservatives not believe in? (d) Traditional institution of state policy (e) Strengthened monarchy (f) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days Ans : (c) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days 6.Name the Italian revolutionary from Genoa. (g) Metternich (b) Johann Gottfried (c) Giuseppe Mazzini (d) None of these Ans : (c) Giuseppe Mazzini 7.Which language was spoken for purposes of diplomacy in the mid 18th century in Europe? (h) German (b) English (c) French (d) Spanish Ans : (c) French 8.What was ‘Young Italy’ ? (i) Vision of Italy (b) Secret society (c) National anthem of Italy (d) None of these Ans : (b) Secret society WORKED FROM HOME 9.Treaty of Constantinople recognised .......... as an independent nation. -

By Filippo Sabetti Mcgill University the MAKING of ITALY AS AN

THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE by Filippo Sabetti McGill University THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE In his reflections on the history of European state-making, Charles Tilly notes that the victory of unitary principles of organiza- tion has obscured the fact, that federal principles of organization were alternative design criteria in The Formation of National States in West- ern Europe.. Centralized commonwealths emerged from the midst of autonomous, uncoordinated and lesser political structures. Tilly further reminds us that "(n)othing could be more detrimental to an understanding of this whole process than the old liberal conception of European history as the gradual creation and extension of political rights .... Far from promoting (representative) institutions, early state-makers 2 struggled against them." The unification of Italy in the nineteenth century was also a victory of centralized principles of organization but Italian state- making or Risorgimento differs from earlier European state-making in at least three respects. First, the prospects of a single political regime for the entire Italian peninsula and islands generated considerable debate about what model of government was best suited to a population that had for more than thirteen hundred years lived under separate and diverse political regimes. The system of government that emerged was the product of a conscious choice among alternative possibilities con- sidered in the formulation of the basic rules that applied to the organi- zation and conduct of Italian governance. Second, federal principles of organization were such a part of the Italian political tradition that the victory of unitary principles of organization in the making of Italy 2 failed to obscure or eclipse them completely. -

5 How Did Nationalism Lead to a United Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815

#5 How did nationalism lead to a united Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815 • Italy had been divided up • Controlled by ruling families of Austria, France & Spain • Secretive group of revolutionaries formed in S. Italy – inspired by French Rev. 1848 • Nationalistic feelings were intensifying– throughout the 8 Italian city-states • Revolts were led by Giuseppe Mazzini – returned from exile • Leader of the “Young Italy” movement – dedicated to securing “for Italy Unity, Independence & Liberty” These Revolts Failed • Looked to Kingdom of Sardinia to rule a unified Italy – agreed they would rather have a unified Italy with a monarch than a lot of foreign powers ruling over separate states • “Risorgimento” Count Cavour & King Victor Emmanuel II • Wanted to unify Italy – make Piedmont- Sardinia the model for unification • Began public works, building projects, political reform • Next step -- get Austria out of the Italian Peninsula • Outbreak of Crimean War -- France & Britain on one side, Russia on the other • Piedmont-Sardinia saw a chance to earn some respect and make a name for itself • They were victorious and Sardinia was able to attend the peace conference. As a result of this, Piedmont- Sardinia gained the support of Napoleon III. Giuseppe Garibaldi • Italian Nationalist • Invaded S. Italy with his followers, the Red Shirts • Also supported King Victor Emmanuel – Piedmont Sardinia was only nation capable of defeating Austria • Aided by Sardinia – Cavour gave firearms to Garibaldi • Guerrilla warfare (hit & run tactics) Unified Italy • Constitutional monarchy was established – Under King Victor Emmanuel • Rome – new capital • Pope went into “exile” Garibaldi And Victor Emmanuel "Right Leg in the Boot at Last" Problems of Unification • Inexperience in self- government • Tradition of regional independence • Large part of population was illiterate • Lots of debt • Had to build an infrastructure • Severe economic & cultural divisions • (S – poor, N – more industrialized) • Centralized state, but weak Independence • Lots of people left for the U.S. -

Unification of Italy 1792 to 1925 French Revolutionary Wars to Mussolini

UNIFICATION OF ITALY 1792 TO 1925 FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY WARS TO MUSSOLINI ERA SUMMARY – UNIFICATION OF ITALY Divided Italy—From the Age of Charlemagne to the 19th century, Italy was divided into northern, central and, southern kingdoms. Northern Italy was composed of independent duchies and city-states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire; the Papal States of central Italy were ruled by the Pope; and southern Italy had been ruled as an independent Kingdom since the Norman conquest of 1059. The language, culture, and government of each region developed independently so the idea of a united Italy did not gain popularity until the 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars wreaked havoc on the traditional order. Italian Unification, also known as "Risorgimento", refers to the period between 1848 and 1870 during which all the kingdoms on the Italian Peninsula were united under a single ruler. The most well-known character associated with the unification of Italy is Garibaldi, an Italian hero who fought dozens of battles for Italy and overthrew the kingdom of Sicily with a small band of patriots, but this romantic story obscures a much more complicated history. The real masterminds of Italian unity were not revolutionaries, but a group of ministers from the kingdom of Sardinia who managed to bring about an Italian political union governed by ITALY BEFORE UNIFICATION, 1792 B.C. themselves. Military expeditions played an important role in the creation of a United Italy, but so did secret societies, bribery, back-room agreements, foreign alliances, and financial opportunism. Italy and the French Revolution—The real story of the Unification of Italy began with the French conquest of Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars. -

Enjoy Your Visit!!!

declared war on Austria, in alliance with the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and attacked the weakened Austria in her Italian possessions. embarked to Sicily to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the But Piedmontese Army was defeated by Radetzky; Charles Albert abdicated Bourbons. Garibaldi gathered 1.089 volunteers: they were poorly armed in favor of his son Victor Emmanuel, who signed the peace treaty on 6th with dated muskets and were dressed in a minimalist uniform consisting of August 1849. Austria reoccupied Northern Italy. Sardinia wasn’t able to beat red shirts and grey trousers. On 5th May they seized two steamships, which Austria alone, so it had to look for an alliance with European powers. they renamed Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo, at Quarto, near Genoa. On 11th May they landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily; on 15th they Room 8 defeated Neapolitan troops at Calatafimi, than they conquered Palermo on PALAZZO MORIGGIA the 29th , after three days of violent clashes. Following the victory at Milazzo (29th May) they were able to control all the island. The last battle took MUSEO DEL RISORGIMENTO THE DECADE OF PREPARATION 1849-1859 place on 1st October at Volturno, where twenty-one thousand Garibaldini The Decade of Preparation 1849-1859 (Decennio defeated thirty thousand Bourbons soldiers. The feat was a success: Naples di Preparazione) took place during the last years of and Sicily were annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia by a plebiscite. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY HISTORY LABORATORY Risorgimento, ended in 1861 with the proclamation CIVIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION of the Kingdom of Italy, guided by Vittorio Emanuele Room 13-14 II. -

Giuseppe Mazzini's International Political Thought

Copyrighted Material INTRODUCTION Giuseppe Mazzini’s International Political Thought Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–72) is today largely remembered as the chief inspirer and leading political agitator of the Italian Risorgimento. Yet Mazzini was not merely an Italian patriot, and his influence reached far beyond his native country and his century. In his time, he ranked among the leading European intellectual figures, competing for public atten tion with Mikhail Bakunin and Karl Marx, John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville. According to his friend Alexander Herzen, the Russian political activist and writer, Mazzini was the “shining star” of the dem ocratic revolutions of 1848. In those days Mazzini’s reputation soared so high that even the revolution’s ensuing defeat left most of his Euro pean followers with a virtually unshakeable belief in the eventual tri umph of their cause.1 Mazzini was an original, if not very systematic, political thinker. He put forward principled arguments in support of various progressive causes, from universal suffrage and social justice to women’s enfran chisement. Perhaps most fundamentally, he argued for a reshaping of the European political order on the basis of two seminal principles: de mocracy and national selfdetermination. These claims were extremely radical in his time, when most of continental Europe was still under the rule of hereditary kingships and multinational empires such as the Habs burgs and the ottomans. Mazzini worked primarily on people’s minds and opinions, in the belief that radical political change first requires cultural and ideological transformations on which to take root. He was one of the first political agitators and public intellectuals in the contemporary sense of the term: not a solitary thinker or soldier but rather a political leader who sought popular support and participa tion. -

3.-Unifying-Italy.Pdf

WH07_TE_ch22_s03_na_s.fm Page 700 Tuesday, February 13, 2007 4:52wh07_se_ch22_s03_s.fm PM Page 700 Wednesday, December 6, 2006 3:15 PM Flag of Italy, 1833 Step-by-Step WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO SECTION Instruction 3 Stirrings of Nationalism After a failed revolution against Austrian rule in northern Objectives Italy, many rebels, fearing retribution, begged for funds to As you teach this section, keep students pay for safe passage to Spain. Giuseppe Mazzini (mat SEE focused on the following objectives to help nee), still a boy, described his reaction to the situation: them answer the Section Focus Question “ He (a rebel) held out a white handkerchief, merely say- and master core content. ing, ‘For the refugees of Italy.’ My mother . dropped 3 some money into the handkerchief. That day was the ■ List the key obstacles to Italian unity. first in which a confused idea presented itself to my mind ■ Understand what roles Count Camillo . an idea that we Italians could and therefore ought to Cavour and Giuseppe Garibaldi played struggle for the liberty of our country. .” in the struggle for Italy. —Giuseppe Mazzini, Life and Writings Focus Question How did influential leaders help to create ■ Describe the challenges that faced the Giuseppe Mazzini, a unified Italy? new nation of Italy. around 1865 Unifying Italy Prepare to Read Objectives Although the people of the Italian peninsula spoke the same lan- Build Background Knowledge L3 • List the key obstacles to Italian unity. guage, they had not experienced political unity since Roman Ask students to recall the issues facing • Understand what roles Count Camillo Cavour times. -

Buonarroti and His International Secret Societies

ARTHUR LEHNING BUONARROTI AND HIS INTERNATIONAL SECRET SOCIETIES On the 27th May 1797 the High Court at Vendome sentenced Babeuf to death and Buonarroti, then 36 years old, to deportation, but this being postponed there followed a long life of imprisonment and exile. Buonarroti led a mysterious life, and our knowledge about certain phases of his life and activities since Vendome is incomplete. Buonar- roti has, of course, always been known as one of the important actors of the conspiracy connected with the name of Babeuf, and as the author of a book, dealing with this conspiracy. This rare and famous book, published in 1828 1, was mainly regarded as the historical account of an eye-witness and participant of a post-thermidorian episode of the French Revolution. The book, however, was also a landmark in the historiography of the French Revolution, and did much for the revaluation and the rehabilitation of Robespierre and the revival of the Jacobin tradition under the Monarchy of July. By exposing the social implications of the Terror, and by a detailed account of the organisation and the methods and the aims of the conspiracy of 1796, the book became a textbook for the communist movement in the 1830's and fourties in France, and the fundamental source for its ideology. In fact, with the "Conspiration" started the Jacobin trend in European socialism. In speaking of his widespread influence 2 one has to consider differ- ent aspects: his communist ideology, his conspirative and insurrectio- nal methods and his theory of a revolutionary dictatorship. In what has always been called somewhat vaguely Babouvism and neo-Babouvism there has never been made a distinction between the ideas of Babeuf and Buonarroti, nor has the question ever been asked as to how far the 1 Conspiration pour l'egalite dite de Babeuf, Bruxelles 1828, 2 vol. -

Mazzini's Filosofia Della Musica: an Early Nineteenth-Century Vision Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture MAZZINI’S FILOSOFIA DELLA MUSICA: AN EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY VISION OF OPERATIC REFORM A Thesis in Musicology by Claire Thompson © 2012 Claire Thompson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2012 ii The thesis of Claire Thompson was reviewed and approved* by the following: Charles Youmans Associate Professor of Musicology Thesis Adviser Marie Sumner Lott Assistant Professor of Musicology Sue Haug Director of the School of Music *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT Although he is better known for his political writings and for heading a series of failed revolutions in mid-nineteenth century Italy, Giuseppe Mazzini also delved into the realm of music aesthetics with his treatise Filosofia della Musica. Ignoring technical considerations, Mazzini concerned himself with the broader social implications of opera, calling for operatic reform to combat Italian opera’s materialism, its lack of unifying characteristics, and its privileging of melody over all other considerations. Mazzini frames his argument for the transformation of opera into a social art within the context of a larger Hegelian dialectic, which pits Italian music (which Mazzini associates with melody and the individual) against German music (which Mazzini associates with harmony and society). The resulting synthesis, according to Mazzini, would be a moral operatic drama, situating individuals within a greater society, and manifesting itself in a cosmopolitan or pan-European style of music. This thesis explores Mazzini’s treatise, including the context of its creation, the biases it demonstrates, the philosophical issues it raises about the nature and role of music, and the individual details of Mazzini’s vision of reform. -

Study Guide Fall 2016

Santa Reparata International School of Art Academic Year 2016/2017 Contemporary Italy professor dr. Lorenzo Pubblici Study Guide 1. The Italian Unification The notion of Risorgimento in Italian history What is the Risorgimento? • Traditional view: 1815-1871 • Modern view: 1789-1918 • Political Risorgimento and Literary Risorgimento Vittorio Alfieri (1749-1803) and other intellectuals Italy is a Country where the national culture was born before the Nation itself. Let’s see the steps towards the creation of the idea of Italy • Ancient Roman Empire: Augustus and the reform of the provinces • Free citizens were Roman citizen • 476: fall of the Roman Empire, the peninsular unity is not broken • VI Century: Byzantine-Gothic war • End of the VI Century: Lombard invasion, the Peninsula loses its geographical unity • The fusion of the two elements: germanic and latin The Franks • The invasion of the Franks (Charlemagne) breaks the Regnum Langobardorum • The Franks and the desire of autonomy of the Northern Italian cities • The attempts for an unitarian kingdom by Frederick 2nd, and birth of the Communes • The Roman Church remains the only identitarian power in Italy The intellectuals • The Regional States and the Signorie, late Middle Ages • The Humanism and the Rinascimento: Italy, heir of Rome. • Complaining of the actual situation (all the rulers in Italy are foreigners) Dante, Petrarca and Boccaccio and the Italian language • Cosimo dei Medici and Lorenzo as Pater Patriae • Machiavelli and Guicciardini: the central State and the Federal one The French Revolution and the Napoleonic period • The French Revolution, the Enlightenment and the results in Europe and in Italy • Napoleon invades Italy (1796).