By Filippo Sabetti Mcgill University the MAKING of ITALY AS AN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tuscany & Umbria

ITALY Tuscany & Umbria A Guided Walking Adventure Table of Contents Daily Itinerary ........................................................................... 4 Tour Itinerary Overview .......................................................... 10 Tour Facts at a Glance ........................................................... 12 Traveling To and From Your Tour .......................................... 14 Information & Policies ............................................................ 17 Italy at a Glance ..................................................................... 19 Packing List ........................................................................... 24 800.464.9255 / countrywalkers.com 2 © 2015 Otago, LLC dba Country Walkers Travel Style This small-group Guided Walking Adventure offers an authentic travel experience, one that takes you away from the crowds and deep in to the fabric of local life. On it, you’ll enjoy 24/7 expert guides, premium accommodations, delicious meals, effortless transportation, and local wine or beer with dinner. Rest assured that every trip detail has been anticipated so you’re free to enjoy an adventure that exceeds your expectations. And, with our optional Flight + Tour ComboCombo, Florence PrePre----tourtour Extension and Rome PostPost----TourTour Extension to complement this destination, we take care of all the travel to simplify the journey. Refer to the attached itinerary for more details. Overview A walk in the sweeping hills of Tuscany and Umbria is a journey into Italy’s artistic and agricultural heart. Your path follows history, from Florence—where your tour commences—to Siena—an important art center distinguished by its remarkable cathedral—and on to Assisi to view the art treasures of the Basilica of St. Francis. Deep in Umbria, you view Gubbio’s stunning Palazzo dei Consolo and move on to the mosaics decorating Orvieto’s Gothic cathedral. Your stay in the Roman town of Spello—known for its medieval frescoes— inspires with aesthetic balance and timeless charm. -

Multiple Sclerosis in the Campania Region (South Italy): Algorithm Validation and 2015–2017 Prevalence

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Multiple Sclerosis in the Campania Region (South Italy): Algorithm Validation and 2015–2017 Prevalence Marcello Moccia 1,* , Vincenzo Brescia Morra 1, Roberta Lanzillo 1, Ilaria Loperto 2 , Roberta Giordana 3, Maria Grazia Fumo 4, Martina Petruzzo 1, Nicola Capasso 1, Maria Triassi 2, Maria Pia Sormani 5 and Raffaele Palladino 2,6 1 Multiple Sclerosis Clinical Care and Research Centre, Department of Neuroscience, Reproductive Science and Odontostomatology, Federico II University, Via Sergio Pansini 5, 80131 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (V.B.M.); [email protected] (R.L.); [email protected] (M.P.); [email protected] (N.C.) 2 Department of Public Health, Federico II University, 80131 Naples, Italy; [email protected] (I.L.); [email protected] (M.T.); raff[email protected] (R.P.) 3 Campania Region Healthcare System Commissioner Office, 80131 Naples, Italy; [email protected] 4 Regional Healthcare Society (So.Re.Sa), 80131 Naples, Italy; [email protected] 5 Biostatistics Unit, Department of Health Sciences, University of Genoa, 16121 Genoa, Italy; [email protected] 6 Department of Primary Care and Public Health, Imperial College, London SW7 2AZ, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel./Fax: +39-081-7462670 Received: 21 April 2020; Accepted: 12 May 2020; Published: 13 May 2020 Abstract: We aim to validate a case-finding algorithm to detect individuals with multiple sclerosis (MS) using routinely collected healthcare data, and to assess the prevalence of MS in the Campania Region (South Italy). To identify individuals with MS living in the Campania Region, we employed an algorithm using different routinely collected healthcare administrative databases (hospital discharges, drug prescriptions, outpatient consultations with payment exemptions), from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2017. -

The Unification of Italy and Germany

EUROPEAN HISTORY Unit 10 The Unification of Italy and Germany Form 4 Unit 10.1 - The Unification of Italy Revolution in Naples, 1848 Map of Italy before unification. Revolution in Rome, 1848 Flag of the Kingdom of Italy, 1861-1946 1. The Early Phase of the Italian Risorgimento, 1815-1848 The settlements reached in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna had restored Austrian domination over the Italian peninsula but had left Italy completely fragmented in a number of small states. The strongest and most progressive Italian state was the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in north-western Italy. At the Congress of Vienna this state had received the lands of the former Republic of Genoa. This acquisition helped Sardinia-Piedmont expand her merchant fleet and trade centred in the port of Genoa. There were three major obstacles to unity at the time of the Congress of Vienna: The Austrians occupied Lombardy and Venetia in Northern Italy. The Papal States controlled Central Italy. The other Italian states had maintained their independence: the Kingdom of Sardinia, also called Piedmont-Sardinia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (ruler by the Bourbon dynasty) and the Duchies of Tuscany, Parma and Modena (ruled by relatives of the Austrian Habsburgs). During the 1820s the Carbonari secret society tried to organize revolts in Palermo and Naples but with very little success, mainly because the Carbonari did not have the support of the peasants. Then came Giuseppe Mazzini, a patriotic writer who set up a national revolutionary movement known as Young Italy (1831). Mazzini was in favour of a united republic. -

The Unification of Italy

New Dorp High School Social Studies Department AP Global Mr. Hubbs & Mrs. Zoleo The Unification of Italy While nationalism destroyed empires, it also built nations. Italy was one of the countries to form from the territories of the crumbling empires. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Austria ruled the Italian provinces of Venetia and Lombardy in the north, and several small states. In the south, the Spanish Bourbon family ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Nevertheless, between 1815 and 1848, increasing numbers of Italians were no longer content to live under foreign rulers. Amid growing discontent, two leaders appeared—one was idealistic, the other practical. They had different personalities and pursued different goals. But each contributed to the Unification of Italy. The Movement for Unity Begins In 1832, an idealistic 26-year-old Italian named Guiseppe Mazzini organized a nationalist group called, Young Italy. Similarly, youth were the leaders and custodians of the nineteenth century nationalist movements. The Napoleonic Wars were lead principally by younger men. Napoleon was 35 years of age when crowned Emperor. As nationalism spread across Europe the pattern continued. People over 40 were excluded from Mazzini's organization. During the violent year of 1848, revolts broke out in eight states on the Italian Peninsula. Mazzini briefly headed a republican government in Rome. He believed that nation-states were the best hope for social justice, democracy, and peace in Europe. However, the 1848 rebellions failed in Italy as they did elsewhere in Europe. The foreign rulers of the Italian states drove Mazzini and other nationalist leaders into exile. -

QUALESTORIA. Rivista Di Storia Contemporanea. L'italia E La

«Qualestoria» n.1, giugno 2021, pp. 163-186 DOI: 10.13137/0393-6082/32191 https://www.openstarts.units.it/handle/10077/21200 163 Culture, arts, politics. Italy in Ivan Meštrović’s and Bogdan Radica’s discourses between the two World Wars di Maciej Czerwiński In this article the activity and discourses of two Dalmatian public figures are taken into consideration: the sculptor Ivan Meštrović and the journalist Bogdan Radica. They both had an enormous influence on how the image of Italy was created and disseminated in Yugoslavia, in particular in the 1920s and 1930s. The analysis of their discourses is interpreted in terms of the concept of Dalmatia within a wider Mediterranean basin which also refers to two diverse conceptualizations of Yugoslavism, cultural and politi- cal. Meštrović’s vision of Dalmatia/Croatia/Yugoslavia was based on his rural hinterland idiom enabling him to embrace racial and cultural Yugoslavism. In contrast, Radica, in spite of having a pro-Yugoslav orientation during the same period, did not believe in race, so for him the idea of Croat-Serb unity was more a political issue (to a lesser extent a cultural one). Keywords: Dalmatia, Yugoslav-Italian relationships, Croatianness, Yugoslavism, Bor- derlands Parole chiave: Dalmazia, Relazioni Jugoslavia-Italia, Croaticità, Jugoslavismo, Aree di confine Introduction This article takes into consideration the activity and discourses of the sculptor Ivan Meštrović and the journalist Bogdan Radica1. The choice of these two figures from Dalmatia, though very different in terms of their profession and political status in the interwar Yugoslav state (1918-41), has an important justification. Not only they both were influenced by Italian culture and heritage (displaying the typical Dalmatian ambivalence towards politics), but they also evaluated Italian heritage and politics in the Croatian/Yugoslav public sphere. -

The North-South Divide in Italy: Reality Or Perception?

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk EUROPEAN SPATIAL RESEARCH AND POLICY Volume 25 2018 Number 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.25.1.03 Dario MUSOLINO∗ THE NORTH-SOUTH DIVIDE IN ITALY: REALITY OR PERCEPTION? Abstract. Although the literature about the objective socio-economic characteristics of the Italian North- South divide is wide and exhaustive, the question of how it is perceived is much less investigated and studied. Moreover, the consistency between the reality and the perception of the North-South divide is completely unexplored. The paper presents and discusses some relevant analyses on this issue, using the findings of a research study on the stated locational preferences of entrepreneurs in Italy. Its ultimate aim, therefore, is to suggest a new approach to the analysis of the macro-regional development gaps. What emerges from these analyses is that the perception of the North-South divide is not consistent with its objective economic characteristics. One of these inconsistencies concerns the width of the ‘per- ception gap’, which is bigger than the ‘reality gap’. Another inconsistency concerns how entrepreneurs perceive in their mental maps regions and provinces in Northern and Southern Italy. The impression is that Italian entrepreneurs have a stereotyped, much too negative, image of Southern Italy, almost a ‘wall in the head’, as also can be observed in the German case (with respect to the East-West divide). Keywords: North-South divide, stated locational preferences, perception, image. 1. INTRODUCTION The North-South divide1 is probably the most known and most persistent charac- teristic of the Italian economic geography. -

Using Italian

This page intentionally left blank Using Italian This is a guide to Italian usage for students who have already acquired the basics of the language and wish to extend their knowledge. Unlike conventional grammars, it gives special attention to those areas of vocabulary and grammar which cause most difficulty to English speakers. Careful consideration is given throughout to questions of style, register, and politeness which are essential to achieving an appropriate level of formality or informality in writing and speech. The book surveys the contemporary linguistic scene and gives ample space to the new varieties of Italian that are emerging in modern Italy. The influence of the dialects in shaping the development of Italian is also acknowledged. Clear, readable and easy to consult via its two indexes, this is an essential reference for learners seeking access to the finer nuances of the Italian language. j. j. kinder is Associate Professor of Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He has published widely on the Italian language spoken by migrants and their children. v. m. savini is tutor in Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He works as both a tutor and a translator. Companion titles to Using Italian Using French (third edition) Using Italian Synonyms A guide to contemporary usage howard moss and vanna motta r. e. batc h e lor and m. h. of f ord (ISBN 0 521 47506 6 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 64177 2 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 47573 2 paperback) (ISBN 0 521 64593 X paperback) Using French Vocabulary Using Spanish jean h. -

![Italian: Repubblica Italiana),[7][8][9][10] Is a Unitary Parliamentary Republic Insouthern Europe](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6369/italian-repubblica-italiana-7-8-9-10-is-a-unitary-parliamentary-republic-insouthern-europe-356369.webp)

Italian: Repubblica Italiana),[7][8][9][10] Is a Unitary Parliamentary Republic Insouthern Europe

Italy ( i/ˈɪtəli/; Italian: Italia [iˈtaːlja]), officially the Italian Republic (Italian: Repubblica italiana),[7][8][9][10] is a unitary parliamentary republic inSouthern Europe. Italy covers an area of 301,338 km2 (116,347 sq mi) and has a largely temperate climate; due to its shape, it is often referred to in Italy as lo Stivale (the Boot).[11][12] With 61 million inhabitants, it is the 5th most populous country in Europe. Italy is a very highly developed country[13]and has the third largest economy in the Eurozone and the eighth-largest in the world.[14] Since ancient times, Etruscan, Magna Graecia and other cultures have flourished in the territory of present-day Italy, being eventually absorbed byRome, that has for centuries remained the leading political and religious centre of Western civilisation, capital of the Roman Empire and Christianity. During the Dark Ages, the Italian Peninsula faced calamitous invasions by barbarian tribes, but beginning around the 11th century, numerous Italian city-states rose to great prosperity through shipping, commerce and banking (indeed, modern capitalism has its roots in Medieval Italy).[15] Especially duringThe Renaissance, Italian culture thrived, producing scholars, artists, and polymaths such as Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo, Michelangelo and Machiavelli. Italian explorers such as Polo, Columbus, Vespucci, and Verrazzano discovered new routes to the Far East and the New World, helping to usher in the European Age of Discovery. Nevertheless, Italy would remain fragmented into many warring states for the rest of the Middle Ages, subsequently falling prey to larger European powers such as France, Spain, and later Austria. -

Stewart2019.Pdf

Political Change and Scottish Nationalism in Dundee 1973-2012 Thomas A W Stewart PhD Thesis University of Edinburgh 2019 Abstract Prior to the 2014 independence referendum, the Scottish National Party’s strongest bastions of support were in rural areas. The sole exception was Dundee, where it has consistently enjoyed levels of support well ahead of the national average, first replacing the Conservatives as the city’s second party in the 1970s before overcoming Labour to become its leading force in the 2000s. Through this period it achieved Westminster representation between 1974 and 1987, and again since 2005, and had won both of its Scottish Parliamentary seats by 2007. This performance has been completely unmatched in any of the country’s other cities. Using a mixture of archival research, oral history interviews, the local press and memoires, this thesis seeks to explain the party’s record of success in Dundee. It will assess the extent to which the character of the city itself, its economy, demography, geography, history, and local media landscape, made Dundee especially prone to Nationalist politics. It will then address the more fundamental importance of the interaction of local political forces that were independent of the city’s nature through an examination of the ability of party machines, key individuals and political strategies to shape the city’s electoral landscape. The local SNP and its main rival throughout the period, the Labour Party, will be analysed in particular detail. The thesis will also take time to delve into the histories of the Conservatives, Liberals and Radical Left within the city and their influence on the fortunes of the SNP. -

Ibn Hamdis." 26-27: Cormo

NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains pages with slanted print. Pages were microfilmed as received. This reproduction is the best copy available Medieval Sicilian fyric poetry: Poets at the courts of Roger IT and Frederick II Karla Mdette A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of PhD Graduate Department of Medieval Studies University of Toronto O Copyright by Karla Mdlette 1998 National Library BibIioth&que nationale me1 of-& du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, nre Wellington OttawaON K1AW OttawaON K1AON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde me licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distri'bute or sell reproduire, prtter, distnbuer cu copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de nlicrofiche/film, de reprod~ctior~sur papier ou sur format eectronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts from it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celleci ne doivent Stre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Medieval Sicilian Lyric Poetry: Poets at the Courts of Roger lI and Frederick II Submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of PhD, 1998 Karla Mallette Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Toronto During the twelfth century, a group of poets at the Norman court in Sicily composed traditional Arabic panegyrics in praise of the kingdom's Christian monarchs. -

National Identity As Part of Ethical History Mirko Tasic, Webster

Conceptual Reality: National Identity as Part of Ethical History Mirko Tasic, Webster University, Thailand The Asian Conference on Ethics, Religion & Philosophy 2019 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract This article explores the concept of national identity as ‘acceptable reality’ from three different perspectives: individuals, the society as a whole, and the international community. National identity and the process of its formation has been a hot topic in various fields of social science. However, most of the academic researches of national identity usually employ atomistic perspective of a nation-territory-sovereignty axis imposed by a long lasting dominance of rationalist theoretical approaches. In the quest to define what is identity of a nation and how it has been developed, the nation itself was omitted in all its complexity and taken as a self-explanatory notion. The process of admission of a nation in the pantheon of ethical sovereigns precedes the process of conceptualization and historical foundation of national identity. Thus, who, why and how is accepting and being accepted, rather than what is the identity of a nation which will be proudly exposed in the showcase of Oscar winning ethical nations, or dumped in the field of unethical (histories/identities) golden raspberries. The case study analysis of several European countries confirms the main assumption of this study, stated: the national identity is recognized as such only as part of ethical history, which again will determine the scope and concept of nation itself. This implies that national identity does not exist independently before the process of ethicalization. Keywords: national identity, ethical history, Tabula Rogeriana, poststructuralism iafor The International Academic Forum www.iafor.org Introduction The social sector often blurs the straight lines drawn in the political domain. -

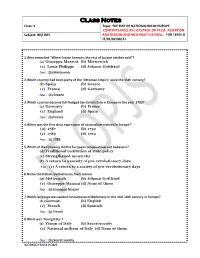

Mcq Drill for Practice—Test Yourself (Answer Key at the Last)

Class Notes Class: X Topic: THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN EUROPE CONTENTS-MCQ ,FILL UPS,TRUE OR FALSE, ASSERTION Subject: HISTORY AND REASON AND MCQ PRACTICE DRILL… FOR TERM-I/ JT/01/02/08/21 1.Who remarked “When France Sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold”? (a) Giuseppe Mazzini (b) Metternich (c) Louis Philippe (d) Johann Gottfried Ans : (b) Metternich 2.Which country had been party of the ‘Ottoman Empire’ since the 15th century? (b) Spain (b) Greece (c) France (d) Germany Ans : (b) Greece 3.Which country became full-fledged territorial state in Europe in the year 1789? (c) Germany (b) France (c) England (d) Spain Ans : (b) France 4.When was the first clear expression of nationalism noticed in Europe? (a) 1787 (b) 1759 (c) 1789 (d) 1769 Ans : (c) 1789 5.Which of the following did the European conservatives not believe in? (d) Traditional institution of state policy (e) Strengthened monarchy (f) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days Ans : (c) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days 6.Name the Italian revolutionary from Genoa. (g) Metternich (b) Johann Gottfried (c) Giuseppe Mazzini (d) None of these Ans : (c) Giuseppe Mazzini 7.Which language was spoken for purposes of diplomacy in the mid 18th century in Europe? (h) German (b) English (c) French (d) Spanish Ans : (c) French 8.What was ‘Young Italy’ ? (i) Vision of Italy (b) Secret society (c) National anthem of Italy (d) None of these Ans : (b) Secret society WORKED FROM HOME 9.Treaty of Constantinople recognised .......... as an independent nation.