The Unification of Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timeline / Before 1800 to After 1930 / ITALY

Timeline / Before 1800 to After 1930 / ITALY Date Country Theme 1800 - 1814 Italy Cities And Urban Spaces In the Napoleonic age, monumental architecture is intended to celebrate the glory of the new regime. An example of that is the Foro Bonaparte, in the area around the Sforza’s Castle in Milan (a project by Giovanni Antonio Antolini). 1800s - 1850s Italy Travelling The “Grand Tour” falls out of vogue; it used to be a period of educational travel, popular among the European aristocrats in the 17th and 18th centuries. Its primary destination was Italy. In the second half of the 19th century, vanguard artists no longer looked at Roman antiquities and Renaissance for inspiration. 1807 - 1837 Italy Cities And Urban Spaces In Milan, Luigi Cagnola completes the construction of the Arch of Peace, started during the Napoleonic age and inspired by the Arc du Carrousel in Paris. The stunning architectures of the Napoleonic age use arches, obelisks and allegorical groups of Roman and French classical inspiration. 1809 Italy Music, Literature, Dance And Fashion Giacomo Leopardi (1798–1837), philosopher, scholar and one of the greatest Italian poets of all times, writes his first poem. 1815 - 1816 Italy Rediscovering The Past Antonio Canova, acting on behalf of Pope Pio VII, recovers from France several pieces of art belonging to the Papal States, which had been brought to Paris by Napoleon, including the Villa Borghese’s archaeological collection. 1815 - 1860 Italy Political Context Italian “Risorgimento” (movement for national unification). 1815 Italy Political Context The Congress of Vienna decides the restoration of pre-Napoleonic monarchies: Kingdom of Sardinia (Piedmont, Genoa, Sardinia); Kingdom of Two Sicilies (Southern Italy and Sicily), the Papal States (part of Central Italy), Grand Duchy of Tuscany and other smaller states. -

The Unification of Italy and Germany

EUROPEAN HISTORY Unit 10 The Unification of Italy and Germany Form 4 Unit 10.1 - The Unification of Italy Revolution in Naples, 1848 Map of Italy before unification. Revolution in Rome, 1848 Flag of the Kingdom of Italy, 1861-1946 1. The Early Phase of the Italian Risorgimento, 1815-1848 The settlements reached in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna had restored Austrian domination over the Italian peninsula but had left Italy completely fragmented in a number of small states. The strongest and most progressive Italian state was the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in north-western Italy. At the Congress of Vienna this state had received the lands of the former Republic of Genoa. This acquisition helped Sardinia-Piedmont expand her merchant fleet and trade centred in the port of Genoa. There were three major obstacles to unity at the time of the Congress of Vienna: The Austrians occupied Lombardy and Venetia in Northern Italy. The Papal States controlled Central Italy. The other Italian states had maintained their independence: the Kingdom of Sardinia, also called Piedmont-Sardinia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (ruler by the Bourbon dynasty) and the Duchies of Tuscany, Parma and Modena (ruled by relatives of the Austrian Habsburgs). During the 1820s the Carbonari secret society tried to organize revolts in Palermo and Naples but with very little success, mainly because the Carbonari did not have the support of the peasants. Then came Giuseppe Mazzini, a patriotic writer who set up a national revolutionary movement known as Young Italy (1831). Mazzini was in favour of a united republic. -

Mcq Drill for Practice—Test Yourself (Answer Key at the Last)

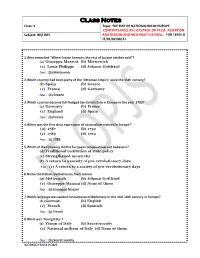

Class Notes Class: X Topic: THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN EUROPE CONTENTS-MCQ ,FILL UPS,TRUE OR FALSE, ASSERTION Subject: HISTORY AND REASON AND MCQ PRACTICE DRILL… FOR TERM-I/ JT/01/02/08/21 1.Who remarked “When France Sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold”? (a) Giuseppe Mazzini (b) Metternich (c) Louis Philippe (d) Johann Gottfried Ans : (b) Metternich 2.Which country had been party of the ‘Ottoman Empire’ since the 15th century? (b) Spain (b) Greece (c) France (d) Germany Ans : (b) Greece 3.Which country became full-fledged territorial state in Europe in the year 1789? (c) Germany (b) France (c) England (d) Spain Ans : (b) France 4.When was the first clear expression of nationalism noticed in Europe? (a) 1787 (b) 1759 (c) 1789 (d) 1769 Ans : (c) 1789 5.Which of the following did the European conservatives not believe in? (d) Traditional institution of state policy (e) Strengthened monarchy (f) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days Ans : (c) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days 6.Name the Italian revolutionary from Genoa. (g) Metternich (b) Johann Gottfried (c) Giuseppe Mazzini (d) None of these Ans : (c) Giuseppe Mazzini 7.Which language was spoken for purposes of diplomacy in the mid 18th century in Europe? (h) German (b) English (c) French (d) Spanish Ans : (c) French 8.What was ‘Young Italy’ ? (i) Vision of Italy (b) Secret society (c) National anthem of Italy (d) None of these Ans : (b) Secret society WORKED FROM HOME 9.Treaty of Constantinople recognised .......... as an independent nation. -

By Filippo Sabetti Mcgill University the MAKING of ITALY AS AN

THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE by Filippo Sabetti McGill University THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE In his reflections on the history of European state-making, Charles Tilly notes that the victory of unitary principles of organiza- tion has obscured the fact, that federal principles of organization were alternative design criteria in The Formation of National States in West- ern Europe.. Centralized commonwealths emerged from the midst of autonomous, uncoordinated and lesser political structures. Tilly further reminds us that "(n)othing could be more detrimental to an understanding of this whole process than the old liberal conception of European history as the gradual creation and extension of political rights .... Far from promoting (representative) institutions, early state-makers 2 struggled against them." The unification of Italy in the nineteenth century was also a victory of centralized principles of organization but Italian state- making or Risorgimento differs from earlier European state-making in at least three respects. First, the prospects of a single political regime for the entire Italian peninsula and islands generated considerable debate about what model of government was best suited to a population that had for more than thirteen hundred years lived under separate and diverse political regimes. The system of government that emerged was the product of a conscious choice among alternative possibilities con- sidered in the formulation of the basic rules that applied to the organi- zation and conduct of Italian governance. Second, federal principles of organization were such a part of the Italian political tradition that the victory of unitary principles of organization in the making of Italy 2 failed to obscure or eclipse them completely. -

5 How Did Nationalism Lead to a United Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815

#5 How did nationalism lead to a united Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815 • Italy had been divided up • Controlled by ruling families of Austria, France & Spain • Secretive group of revolutionaries formed in S. Italy – inspired by French Rev. 1848 • Nationalistic feelings were intensifying– throughout the 8 Italian city-states • Revolts were led by Giuseppe Mazzini – returned from exile • Leader of the “Young Italy” movement – dedicated to securing “for Italy Unity, Independence & Liberty” These Revolts Failed • Looked to Kingdom of Sardinia to rule a unified Italy – agreed they would rather have a unified Italy with a monarch than a lot of foreign powers ruling over separate states • “Risorgimento” Count Cavour & King Victor Emmanuel II • Wanted to unify Italy – make Piedmont- Sardinia the model for unification • Began public works, building projects, political reform • Next step -- get Austria out of the Italian Peninsula • Outbreak of Crimean War -- France & Britain on one side, Russia on the other • Piedmont-Sardinia saw a chance to earn some respect and make a name for itself • They were victorious and Sardinia was able to attend the peace conference. As a result of this, Piedmont- Sardinia gained the support of Napoleon III. Giuseppe Garibaldi • Italian Nationalist • Invaded S. Italy with his followers, the Red Shirts • Also supported King Victor Emmanuel – Piedmont Sardinia was only nation capable of defeating Austria • Aided by Sardinia – Cavour gave firearms to Garibaldi • Guerrilla warfare (hit & run tactics) Unified Italy • Constitutional monarchy was established – Under King Victor Emmanuel • Rome – new capital • Pope went into “exile” Garibaldi And Victor Emmanuel "Right Leg in the Boot at Last" Problems of Unification • Inexperience in self- government • Tradition of regional independence • Large part of population was illiterate • Lots of debt • Had to build an infrastructure • Severe economic & cultural divisions • (S – poor, N – more industrialized) • Centralized state, but weak Independence • Lots of people left for the U.S. -

Unification of Italy 1792 to 1925 French Revolutionary Wars to Mussolini

UNIFICATION OF ITALY 1792 TO 1925 FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY WARS TO MUSSOLINI ERA SUMMARY – UNIFICATION OF ITALY Divided Italy—From the Age of Charlemagne to the 19th century, Italy was divided into northern, central and, southern kingdoms. Northern Italy was composed of independent duchies and city-states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire; the Papal States of central Italy were ruled by the Pope; and southern Italy had been ruled as an independent Kingdom since the Norman conquest of 1059. The language, culture, and government of each region developed independently so the idea of a united Italy did not gain popularity until the 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars wreaked havoc on the traditional order. Italian Unification, also known as "Risorgimento", refers to the period between 1848 and 1870 during which all the kingdoms on the Italian Peninsula were united under a single ruler. The most well-known character associated with the unification of Italy is Garibaldi, an Italian hero who fought dozens of battles for Italy and overthrew the kingdom of Sicily with a small band of patriots, but this romantic story obscures a much more complicated history. The real masterminds of Italian unity were not revolutionaries, but a group of ministers from the kingdom of Sardinia who managed to bring about an Italian political union governed by ITALY BEFORE UNIFICATION, 1792 B.C. themselves. Military expeditions played an important role in the creation of a United Italy, but so did secret societies, bribery, back-room agreements, foreign alliances, and financial opportunism. Italy and the French Revolution—The real story of the Unification of Italy began with the French conquest of Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2006 Version

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2006 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/ris/key_ris_index.htm. Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8 th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9 th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands . Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 7, 2 nd edition, as amended by COP9 Resolution IX.1 Annex B). A 3 rd edition of the Handbook, incorporating these amendments, is in preparation and will be available in 2006. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY . Directorate General for Nature Protection - Ministry o DD MM YY Environment and Nature Protection – Via Capitan Bavastro 174 – I-00100 ROMA [email protected] Designation date Site Reference Number 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: 12 June 2006 3. Country: Italy 4. -

Integrazione Dati

Area delle MAINARDE Verso una strategia nazionale per le aree interne – Regione Molise AREA DELLE MAINARDE 1M. Trend della popolazione 1991-2011 (Area delle Mainarde, 13 comuni) ............................................................................................................................................. 2 2M. Indici demografici: indice di vecchiaia, di dipendenza dei giovani e degli anziani per l’area delle Mainarde .................................................................................... 3 3M. Analisi della struttura demografica Area delle Mainarde ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 4M. Comuni delle province di Campobasso ed Isernia rientranti nel Patto Trigno Sinello. ....................................................................................................................... 6 5M. Sovrapposizione Area delle Mainarde con macro aree PSR 2007-13, Unione dei comini del Molise ed ATS .................................................................................... 7 6M. Servizi Scolastici Area delle Mainarde .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 7M. Servizi per Anziani Area delle Mainarde ........................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Fascist Italy Collection Bernath Mss 495

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8988cmq No online items Guide to the Fascist Italy collection Bernath Mss 495 Finding aid prepared by Wyatt Young, 2016; revised by Zachary Liebhaber, 2019. UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Research Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara 93106-9010 [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections 2016 August 9; 2019 Guide to the Fascist Italy Bernath Mss 495 1 collection Bernath Mss 495 Title: Fascist Italy collection Identifier/Call Number: Bernath Mss 495 Contributing Institution: UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Research Collections Language of Material: Italian Physical Description: 4.21 linear feet(1 half-size document box, 1 map cabinet drawer) Date (inclusive): circa 1900-1943 Abstract: The Fascist Italy collection comprises books, pamphlets, postcards, sheet music, posters and various propaganda materials from the early to mid 20th century in Italy. Physical Location: Special Research Collections, UC Santa Barbara Library Language of Material: The collection is in Italian. Access Restrictions The collection is open for research. Use Restrictions Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Department of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained. Preferred Citation [Identification of Item], Fascist Italy collection, Bernath Mss 495. Department of Special Collections, UC Santa Barbara Library, University of California, Santa Barbara. -

Enjoy Your Visit!!!

declared war on Austria, in alliance with the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and attacked the weakened Austria in her Italian possessions. embarked to Sicily to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the But Piedmontese Army was defeated by Radetzky; Charles Albert abdicated Bourbons. Garibaldi gathered 1.089 volunteers: they were poorly armed in favor of his son Victor Emmanuel, who signed the peace treaty on 6th with dated muskets and were dressed in a minimalist uniform consisting of August 1849. Austria reoccupied Northern Italy. Sardinia wasn’t able to beat red shirts and grey trousers. On 5th May they seized two steamships, which Austria alone, so it had to look for an alliance with European powers. they renamed Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo, at Quarto, near Genoa. On 11th May they landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily; on 15th they Room 8 defeated Neapolitan troops at Calatafimi, than they conquered Palermo on PALAZZO MORIGGIA the 29th , after three days of violent clashes. Following the victory at Milazzo (29th May) they were able to control all the island. The last battle took MUSEO DEL RISORGIMENTO THE DECADE OF PREPARATION 1849-1859 place on 1st October at Volturno, where twenty-one thousand Garibaldini The Decade of Preparation 1849-1859 (Decennio defeated thirty thousand Bourbons soldiers. The feat was a success: Naples di Preparazione) took place during the last years of and Sicily were annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia by a plebiscite. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY HISTORY LABORATORY Risorgimento, ended in 1861 with the proclamation CIVIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION of the Kingdom of Italy, guided by Vittorio Emanuele Room 13-14 II. -

Mussolini's Ambiguous and Opportunistic Conception of Romanità

“A Mysterious Revival of Roman Passion”: Mussolini’s Ambiguous and Opportunistic Conception of Romanità Benjamin Barron Senior Honors Thesis in History HIST-409-02 Georgetown University Mentored by Professor Foss May 4, 2009 “A Mysterious Revival of Roman Passion”: Mussolini’s Ambiguous and Opportunistic Conception of Romanità CONTENTS Preface and Acknowledgments ii List of Illustrations iii Introduction 1 I. Mussolini and the Power of Words 7 II. The Restrained Side of Mussolini’s Romanità 28 III. The Shift to Imperialism: The Second Italo-Ethiopian War 1935 – 1936 49 IV. Romanità in Mussolini’s New Roman Empire 58 Conclusion 90 Bibliography 95 i PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I first came up with the topic for this thesis when I visited Rome for the first time in March of 2008. I was studying abroad for the spring semester in Milan, and my six-month experience in Italy undoubtedly influenced the outcome of this thesis. In Milan, I grew to love everything about Italy – the language, the culture, the food, the people, and the history. During this time, I traveled throughout all of Italian peninsula and, without the support of my parents, this tremendous experience would not have been possible. For that, I thank them sincerely. This thesis would not have been possible without a few others whom I would like to thank. First and foremost, thank you, Professor Astarita, for all the time you put into our Honors Seminar class during the semester. I cannot imagine how hard it must have been to read all of our drafts so intently. Your effort has not gone unnoticed. -

MOLISE Shorter Travelling Time to Rome the New Railway Lines

MOLISE Shorter travelling time to Rome The new railway lines passing through the Molise region will be faster and, above all, safer. The new line, 49 km long, currently under construction between the stations of Rocca d’Evandro and Vairano, could reduce travelling time between Rome and Campobasso by about 20 minutes. Passengers arriving from Termoli on the Adriatic line could go through Venafro to reach the high-speed Rome-Naples line, which is also under construction, more quickly. The Venafro-Vairano stretch, on the other hand, is in need of technological upgrading. Centralised traffic control (CTC) is being installed on the Molise part of the Adriatic line. This is indispensable for railway safety given that double tracking on parts of the line will increase train speeds. Cleaner water A number of schemes have been promoted in an effort to improve water and sewage networks and upgrade the water purification system. As regards water networks, new equipment has been installed and some existing plant improved. This involved 109 projects spread over 136 municipalities in the region. In addition, 108 km of sewer trunk lines and collectors were laid and 74 new sewage plants put into operation, serving a population of 250,000 out of a total of about 330,000. The Pompei of the Dark Ages In the province of Isernia, major rehabilitation has been carried out in the San Vincenzo al Volturno area, an abbatial settlement founded in the Dark Ages and one of the most important monastic institutions of the Carolingian period, described by some as the Pompei of the Dark Ages.