Giuseppe Mazzini's International Political Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter One: Introduction

CHANGING PERCEPTIONS OF IL DUCE TRACING POLITICAL TRENDS IN THE ITALIAN-AMERICAN MEDIA DURING THE EARLY YEARS OF FASCISM by Ryan J. Antonucci Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2013 Changing Perceptions of il Duce Tracing Political Trends in the Italian-American Media during the Early Years of Fascism Ryan J. Antonucci I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Ryan J. Antonucci, Student Date Approvals: Dr. David Simonelli, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Brian Bonhomme, Committee Member Date Dr. Martha Pallante, Committee Member Date Dr. Carla Simonini, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Associate Dean of Graduate Studies Date Ryan J. Antonucci © 2013 iii ABSTRACT Scholars of Italian-American history have traditionally asserted that the ethnic community’s media during the 1920s and 1930s was pro-Fascist leaning. This thesis challenges that narrative by proving that moderate, and often ambivalent, opinions existed at one time, and the shift to a philo-Fascist position was an active process. Using a survey of six Italian-language sources from diverse cities during the inauguration of Benito Mussolini’s regime, research shows that interpretations varied significantly. One of the newspapers, Il Cittadino Italo-Americano (Youngstown, Ohio) is then used as a case study to better understand why events in Italy were interpreted in certain ways. -

The Unification of Italy and Germany

EUROPEAN HISTORY Unit 10 The Unification of Italy and Germany Form 4 Unit 10.1 - The Unification of Italy Revolution in Naples, 1848 Map of Italy before unification. Revolution in Rome, 1848 Flag of the Kingdom of Italy, 1861-1946 1. The Early Phase of the Italian Risorgimento, 1815-1848 The settlements reached in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna had restored Austrian domination over the Italian peninsula but had left Italy completely fragmented in a number of small states. The strongest and most progressive Italian state was the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in north-western Italy. At the Congress of Vienna this state had received the lands of the former Republic of Genoa. This acquisition helped Sardinia-Piedmont expand her merchant fleet and trade centred in the port of Genoa. There were three major obstacles to unity at the time of the Congress of Vienna: The Austrians occupied Lombardy and Venetia in Northern Italy. The Papal States controlled Central Italy. The other Italian states had maintained their independence: the Kingdom of Sardinia, also called Piedmont-Sardinia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (ruler by the Bourbon dynasty) and the Duchies of Tuscany, Parma and Modena (ruled by relatives of the Austrian Habsburgs). During the 1820s the Carbonari secret society tried to organize revolts in Palermo and Naples but with very little success, mainly because the Carbonari did not have the support of the peasants. Then came Giuseppe Mazzini, a patriotic writer who set up a national revolutionary movement known as Young Italy (1831). Mazzini was in favour of a united republic. -

The Unification of Italy

New Dorp High School Social Studies Department AP Global Mr. Hubbs & Mrs. Zoleo The Unification of Italy While nationalism destroyed empires, it also built nations. Italy was one of the countries to form from the territories of the crumbling empires. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Austria ruled the Italian provinces of Venetia and Lombardy in the north, and several small states. In the south, the Spanish Bourbon family ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Nevertheless, between 1815 and 1848, increasing numbers of Italians were no longer content to live under foreign rulers. Amid growing discontent, two leaders appeared—one was idealistic, the other practical. They had different personalities and pursued different goals. But each contributed to the Unification of Italy. The Movement for Unity Begins In 1832, an idealistic 26-year-old Italian named Guiseppe Mazzini organized a nationalist group called, Young Italy. Similarly, youth were the leaders and custodians of the nineteenth century nationalist movements. The Napoleonic Wars were lead principally by younger men. Napoleon was 35 years of age when crowned Emperor. As nationalism spread across Europe the pattern continued. People over 40 were excluded from Mazzini's organization. During the violent year of 1848, revolts broke out in eight states on the Italian Peninsula. Mazzini briefly headed a republican government in Rome. He believed that nation-states were the best hope for social justice, democracy, and peace in Europe. However, the 1848 rebellions failed in Italy as they did elsewhere in Europe. The foreign rulers of the Italian states drove Mazzini and other nationalist leaders into exile. -

INTRODUCTION 1. Charles Esdaile, the Wars of Napoleon (New York, 1995), Ix; Philip Dwyer, “Preface,” Napoleon and Europe, E

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Charles Esdaile, The Wars of Napoleon (New York, 1995), ix; Philip Dwyer, “Preface,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), ix. 2. Michael Broers, Europe under Napoleon, 1799–1815 (London, 1996), 3. 3. An exception to the Franco-centric bibliography in English prior to the last decade is Owen Connelly, Napoleon’s Satellite Kingdoms (New York, 1965). Connelly discusses the developments in five satellite kingdoms: Italy, Naples, Holland, Westphalia, and Spain. Two other important works that appeared before 1990, which explore the internal developments in two countries during the Napoleonic period, are Gabriel Lovett, Napoleon and the Birth of Modern Spain (New York, 1965) and Simon Schama, Patriots and Liberators: Revolution in the Netherlands, 1780–1813 (London, 1977). 4. Stuart Woolf, Napoleon’s Integration of Europe (London and New York, 1991), 8–13. 5. Geoffrey Ellis, “The Nature of Napoleonic Imperialism,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), 102–5; Broers, Europe under Napoleon, passim. 1 THE FORMATION OF THE NAPOLEONIC EMPIRE 1. Geoffrey Ellis, “The Nature of Napoleonic Imperialism,” Napoleon and Europe, ed. Philip Dwyer (London, 2001), 105. 2. Martyn Lyons, Napoleon Bonaparte and the Legacy of the French Revolution (New York, 1994), 43. 3. Ellis, “The Nature,” 104–5. 4. On the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars and international relations, see Tim Blanning, The French Revolutionary Wars, 1787–1802 (London, 1996); David Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon: the Mind and Method of History’s Greatest Soldier (London, 1966); Owen Connelly, Blundering to Glory: Napoleon’s Military 212 Notes 213 Campaigns (Wilmington, DE, 1987); J. -

Mcq Drill for Practice—Test Yourself (Answer Key at the Last)

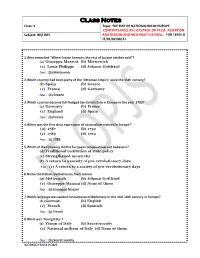

Class Notes Class: X Topic: THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN EUROPE CONTENTS-MCQ ,FILL UPS,TRUE OR FALSE, ASSERTION Subject: HISTORY AND REASON AND MCQ PRACTICE DRILL… FOR TERM-I/ JT/01/02/08/21 1.Who remarked “When France Sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold”? (a) Giuseppe Mazzini (b) Metternich (c) Louis Philippe (d) Johann Gottfried Ans : (b) Metternich 2.Which country had been party of the ‘Ottoman Empire’ since the 15th century? (b) Spain (b) Greece (c) France (d) Germany Ans : (b) Greece 3.Which country became full-fledged territorial state in Europe in the year 1789? (c) Germany (b) France (c) England (d) Spain Ans : (b) France 4.When was the first clear expression of nationalism noticed in Europe? (a) 1787 (b) 1759 (c) 1789 (d) 1769 Ans : (c) 1789 5.Which of the following did the European conservatives not believe in? (d) Traditional institution of state policy (e) Strengthened monarchy (f) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days Ans : (c) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days 6.Name the Italian revolutionary from Genoa. (g) Metternich (b) Johann Gottfried (c) Giuseppe Mazzini (d) None of these Ans : (c) Giuseppe Mazzini 7.Which language was spoken for purposes of diplomacy in the mid 18th century in Europe? (h) German (b) English (c) French (d) Spanish Ans : (c) French 8.What was ‘Young Italy’ ? (i) Vision of Italy (b) Secret society (c) National anthem of Italy (d) None of these Ans : (b) Secret society WORKED FROM HOME 9.Treaty of Constantinople recognised .......... as an independent nation. -

Sub-National Regionalism and the European Union

Sub-National Regionalism and the European Union Roman Szul ABSTRACT The article discusses the relationship between sub-national regionalism and the European Union. Specific attention is paid to the influence of EU accession on regionalism and regionalisation in Poland, especially the situation of the Mazovian Region. It is argued that the relationship between sub-national regionalism and the European Union (as a form of European integration) is determined by four factors: firstly, the decrease of the traditional role of nation state after the second world war and redefinition of international (interstate) relations which made more space both for European integration and regionalism; secondly, practical activities of the EU, especially its funds for regional develop- ment, which prompted or encouraged some countries, especially the new members states from central-eastern Europe, to create regions and stimulated regionalism; thirdly, the recent austerity policy prescribed by the EU in some countries, especially in Spain, which stimulates radicalism of regionalist movements (the case of Catalonia); fourthly, the very ex- istence of the EU and the need to negotiate EU membership which discourages those regionalist-nationalist movements which aim to separate their regions from the existing EU member states while remaining in the EU. Introductory comments The purpose of this paper is to analyse relationships between “sub-national” regionalism and the European Union. The adjective “sub-national” is used to distinguish two completely different meanings of the word “regionalism”: one relating to regions understood as parts of the existing nation states1 and the other (supra-national regionalism) relating to regions as parts of the world and consisting of integration of countries belonging to the same world region2. -

5 How Did Nationalism Lead to a United Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815

#5 How did nationalism lead to a united Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815 • Italy had been divided up • Controlled by ruling families of Austria, France & Spain • Secretive group of revolutionaries formed in S. Italy – inspired by French Rev. 1848 • Nationalistic feelings were intensifying– throughout the 8 Italian city-states • Revolts were led by Giuseppe Mazzini – returned from exile • Leader of the “Young Italy” movement – dedicated to securing “for Italy Unity, Independence & Liberty” These Revolts Failed • Looked to Kingdom of Sardinia to rule a unified Italy – agreed they would rather have a unified Italy with a monarch than a lot of foreign powers ruling over separate states • “Risorgimento” Count Cavour & King Victor Emmanuel II • Wanted to unify Italy – make Piedmont- Sardinia the model for unification • Began public works, building projects, political reform • Next step -- get Austria out of the Italian Peninsula • Outbreak of Crimean War -- France & Britain on one side, Russia on the other • Piedmont-Sardinia saw a chance to earn some respect and make a name for itself • They were victorious and Sardinia was able to attend the peace conference. As a result of this, Piedmont- Sardinia gained the support of Napoleon III. Giuseppe Garibaldi • Italian Nationalist • Invaded S. Italy with his followers, the Red Shirts • Also supported King Victor Emmanuel – Piedmont Sardinia was only nation capable of defeating Austria • Aided by Sardinia – Cavour gave firearms to Garibaldi • Guerrilla warfare (hit & run tactics) Unified Italy • Constitutional monarchy was established – Under King Victor Emmanuel • Rome – new capital • Pope went into “exile” Garibaldi And Victor Emmanuel "Right Leg in the Boot at Last" Problems of Unification • Inexperience in self- government • Tradition of regional independence • Large part of population was illiterate • Lots of debt • Had to build an infrastructure • Severe economic & cultural divisions • (S – poor, N – more industrialized) • Centralized state, but weak Independence • Lots of people left for the U.S. -

Northern Italy: the Alps, Dolomites & Lombardy 2021

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® Northern Italy: The Alps, Dolomites & Lombardy 2021 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Northern Italy: The Alps, Dolomites & Lombardy itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: In my mind, nothing is more idyllic than the mountainous landscapes and rural villages of Alpine Europe. To immerse myself in their pastoral traditions and everyday life, I love to explore rural communities like Teglio, a small village nestled in the Valtellina Valley. You’ll see what I mean when you experience A Day in the Life of a small, family-run farm here where you’ll have the opportunity to meet the owner, walk the grounds, lend a hand with the daily farm chores, and share a traditional meal with your hosts in the farmhouse. You’ll also get a taste for some of the other crafts in the Valley when you visit a locally-owned goat cheese producer and a water-powered mill. But the most moving stories of all were the ones I heard directly from the local people I met. You’ll meet them, too, and hear their personal experiences during a conversation with two political refugeees at a local café in Milan to discuss the deeply divisive issue of immigration in Italy. -

Il Fuoruscitismo Italiano Dal 1922 Al 1943 (*)

IL FUORUSCITISMO ITALIANO DAL 1922 AL 1943 (*) Possiamo organicamente dividere l’emigrazione politica, uno de gli aspetti più rilevanti della storia italiana durante i primi anni del regime fascista, in tre grandi periodi (1). Durante il primo, che va dal 1922 al 1924, tale esodo può apparire motivato da considerazioni economiche, proprio come era avvenuto per molti decenni; tuttavia, anche in questo periodo iniziale, in cui il fascismo non aveva ancora assunto il suo carattere dittatoriale, vi erano motivi politici che face vano capolino nella emigrazione. A migliaia di italiani che, senza un particolare interesse politico, avevano cercato lavoro sui mercati di Francia, Svizzera e Belgio, presto si aggiunsero numerosi altri la voratori, di idee socialiste od anarchiche, che avevano preso parte (1) Le seguenti statistiche possono dare un’idea delle variazioni nell’emigra zione. E’ impossibile, naturalmente, stabilire quanti emigrati fossero spinti prin cipalmente da motivi politici e quanti da considerazioni economiche. Le cifre sono prese dall’« Annuario Statistico italiano », Istituto centrale di Statistica, 1944-48, Serie V (Roma, 1949), I, 49. Anno Emigrazione verso Emigrazione verso Emigraz. ve la Francia l’Europa (Francia compr.) Paesi non Euro 1921 44.782 84.328 116.963 1922 99.464 155.554 125.716 1923 167.982 205.273 184.684 1924 201.715 239.088 125.282 1925 145.529 177.558 101.873 1926 111.252 139.900 122.496 1927 52.784 86.247 132.687 1928 49.351 79.173 70.794 1929 51.001 88.054 61.777 1930 167.209 220.985 59.112 1931 74.115 125.079 40.781 1932 33.516 58.545 24.803 1933 35.745 60.736 22.328 1934 20.725 42.296 26.165 1935 11.666 30.579 26.829 1936 9.614 21.682 19.828 1937 14.717 29.670 30.275 1938 10.551 71.848 27.99-* 1939 2.015 56.625 16.198 L’articolo è qui pubblicato per cortese concessione del « Journal of Central European Affairs » (University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado) che l’ha pubbli cato il 1 aprile 1952 (voi. -

Pius Ix and the Change in Papal Authority in the Nineteenth Century

ABSTRACT ONE MAN’S STRUGGLE: PIUS IX AND THE CHANGE IN PAPAL AUTHORITY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Andrew Paul Dinovo This thesis examines papal authority in the nineteenth century in three sections. The first examines papal issues within the world at large, specifically those that focus on the role of the Church within the political state. The second section concentrates on the authority of Pius IX on the Italian peninsula in the mid-nineteenth century. The third and final section of the thesis focuses on the inevitable loss of the Papal States within the context of the Vatican Council of 1869-1870. Select papal encyclicals from 1859 to 1871 and the official documents of the Vatican Council of 1869-1870 are examined in light of their relevance to the change in the nature of papal authority. Supplementing these changes is a variety of seminal secondary sources from noted papal scholars. Ultimately, this thesis reveals that this change in papal authority became a point of contention within the Church in the twentieth century. ONE MAN’S STRUGGLE: PIUS IX AND THE CHANGE IN PAPAL AUTHORITY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Andrew Paul Dinovo Miami University Oxford, OH 2004 Advisor____________________________________________ Dr. Sheldon Anderson Reader_____________________________________________ Dr. Wietse de Boer Reader_____________________________________________ Dr. George Vascik Contents Section I: Introduction…………………………………………………………………….1 Section II: Primary Sources……………………………………………………………….5 Section III: Historiography……...………………………………………………………...8 Section IV: Issues of Church and State: Boniface VIII and Unam Sanctam...…………..13 Section V: The Pope in Italy: Political Papal Encyclicals….……………………………20 Section IV: The Loss of the Papal States: The Vatican Council………………...………41 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..55 ii I. -

Europe (In Theory)

EUROPE (IN THEORY) ∫ 2007 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Minion with Univers display by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. There is a damaging and self-defeating assumption that theory is necessarily the elite language of the socially and culturally privileged. It is said that the place of the academic critic is inevitably within the Eurocentric archives of an imperialist or neo-colonial West. —HOMI K. BHABHA, The Location of Culture Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: A pigs Eye View of Europe 1 1 The Discovery of Europe: Some Critical Points 11 2 Montesquieu’s North and South: History as a Theory of Europe 52 3 Republics of Letters: What Is European Literature? 87 4 Mme de Staël to Hegel: The End of French Europe 134 5 Orientalism, Mediterranean Style: The Limits of History at the Margins of Europe 172 Notes 219 Works Cited 239 Index 267 Acknowledgments I want to thank for their suggestions, time, and support all the people who have heard, read, and commented on parts of this book: Albert Ascoli, David Bell, Joe Buttigieg, miriam cooke, Sergio Ferrarese, Ro- berto Ferrera, Mia Fuller, Edna Goldstaub, Margaret Greer, Michele Longino, Walter Mignolo, Marc Scachter, Helen Solterer, Barbara Spack- man, Philip Stewart, Carlotta Surini, Eric Zakim, and Robert Zimmer- man. Also invaluable has been the help o√ered by the Ethical Cosmopol- itanism group and the Franklin Humanities Seminar at Duke University; by the Program in Comparative Literature at Notre Dame; by the Khan Institute Colloquium at Smith College; by the Mediterranean Studies groups of both Duke and New York University; and by European studies and the Italian studies program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. -

Enjoy Your Visit!!!

declared war on Austria, in alliance with the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and attacked the weakened Austria in her Italian possessions. embarked to Sicily to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the But Piedmontese Army was defeated by Radetzky; Charles Albert abdicated Bourbons. Garibaldi gathered 1.089 volunteers: they were poorly armed in favor of his son Victor Emmanuel, who signed the peace treaty on 6th with dated muskets and were dressed in a minimalist uniform consisting of August 1849. Austria reoccupied Northern Italy. Sardinia wasn’t able to beat red shirts and grey trousers. On 5th May they seized two steamships, which Austria alone, so it had to look for an alliance with European powers. they renamed Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo, at Quarto, near Genoa. On 11th May they landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily; on 15th they Room 8 defeated Neapolitan troops at Calatafimi, than they conquered Palermo on PALAZZO MORIGGIA the 29th , after three days of violent clashes. Following the victory at Milazzo (29th May) they were able to control all the island. The last battle took MUSEO DEL RISORGIMENTO THE DECADE OF PREPARATION 1849-1859 place on 1st October at Volturno, where twenty-one thousand Garibaldini The Decade of Preparation 1849-1859 (Decennio defeated thirty thousand Bourbons soldiers. The feat was a success: Naples di Preparazione) took place during the last years of and Sicily were annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia by a plebiscite. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY HISTORY LABORATORY Risorgimento, ended in 1861 with the proclamation CIVIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION of the Kingdom of Italy, guided by Vittorio Emanuele Room 13-14 II.