Pius Ix and the Change in Papal Authority in the Nineteenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Plenary Indulgence

Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers Pope Francis Proclaims Plenary Indulgence Affirming the Response to the PAENITENIARIA 10th Year Jubilee Plenary Indulgence Honoring Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers, by Apostolic Papal Decree a Plenary Indulgence is granted to faithful making pilgrimage to Lourdes or experiencing Lourdes in a Virtual Pilgrimage with North American Lourdes Volunteers by fulfilling the usual norms and conditions between July 16, 2013 thru July 15, 2020. APOSTOLICA Jesus Christ lovingly sacrificed Himself for the salvation of humanity. Through Baptism, we are freed from the Original Sin of disobedience inherited from Adam and Eve. With our gift of free will we can choose to sin, personally separating ourselves from God. Although we can be completely forgiven, temporal (temporary) consequences of sin remain. Indulgences are special graces that can rid us of temporal punishment. What is a plenary indulgence? “An indulgence is a remission before God of the temporal punishment Our Lady of Lourdes Hospitality North American Volunteers due to sins whose guilt has already been forgiven.” (CCC 1471) There Public Association of the Christian Faithful and First Hospitality of the Americas are two types of indulgences: plenary and partial. A plenary indulgence www.LourdesVolunteers.org [email protected] removes all of the temporal punishment due to sin; a partial indulgence (315) 476-0026 FAX (419) 730-4540 removes some but not all of the temporal punishment. © 2017 V. 1-18 What is temporal punishment for sin? How can the Church give indulgences? Temporal punishment for sin is the sanctification from attachment to sin, The Church is able to grant indulgences by the purification to holiness needed for us to be able to enter Heaven. -

Anathemas and Fr John Shaw

ANATHEMAS AND FR. JOHN SHAW By Vladimir Moss The Orthodox world was shocked when, in 1965, Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras “lifted the anathemas” on their churches. Metropolitan Philaret led the True Orthodox in protesting that this simply could not be done. The anathemas on the Filioque and other Papist heresies were eternally valid, for falsehood remains falsehood for ever; and as long as the Papists confessed these heresies, they fell under the anathemas. The essential point is this: if an anathema expresses truth, and the bishops who pronounce it are true, then it has power “to the ages of ages”, and nobody can lift it, because it is pronounced not only by the earthly Church, but also by the Heavenly Church, in accordance with the word of the Lord: “Whatever ye [the apostles and their successors] shall bind on earth shall be bound in heaven” (Matthew 18.18). However, following in the footsteps of Athenagoras, we now have a man who thinks he can lift anathemas: Fr. John Shaw. Or rather, Fr. John does not pretend to lift them (that would be a truly Herculean task for a mere priest!). He either (in the case of Patriarch Tikhon and the anathema on the Bolsheviks of 1918) says that a patriarch has lifted it, or (in the case of the ROCOR's anathema against ecumenism of 1983) does something even less plausible: he says it never really happened! The Anathema of 1918 Let us take the first case. On January 19, 1918 Patriarch Tikhon anathematised the Bolsheviks in the following words: “By the power given to Us by God, we forbid you to approach the Mysteries of Christ, we anathematise you, if only you bear Christian names and although by birth you belong to the Orthodox Church. -

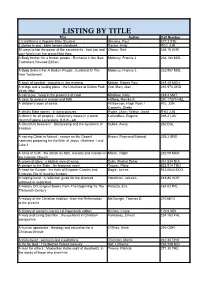

Parish Library Listing

LISTING BY TITLE Title Author Call Number 2 Corinthians (Lifeguide Bible Studies) Stevens, Paul 227.3 STE 3 stories in one : bible heroes storybook Rector, Andy REC JUN 50 ways to tap the power of the sacraments : how you and Ghezzi, Bert 234.16 GHE your family can live grace-filled lives A Body broken for a broken people : Eucharist in the New Moloney, Francis J. 234.163 MOL Testament Revised Edition A Body Broken For A Broken People : Eucharist In The Moloney, Francis J. 232.957 MOL New Testament A book of comfort : thoughts in late evening Mohan, Robert Paul 248.48 MOH A bridge and a resting place : the Ursulines at Dutton Park Ord, Mary Joan 255.974 ORD 1919-1980 A call to joy : living in the presence of God Matthew, Kelly 248.4 MAT A case for peace in reason and faith Hellwig, Monika K. 291.17873 HEL A children's book of saints Williamson, Hugh Ross / WIL JUN Connelly, Sheila A child's Bible stories : in living pictures Ryder, Lilian / Walsh, David RYD JUN A church for all peoples : missionary issues in a world LaVerdiere, Eugene 266.2 LAV church Eugene LaVerdiere, S.S.S - edi A Church to believe in : Discipleship and the dynamics of Dulles, Avery 262 DUL freedom A coming Christ in Advent : essays on the Gospel Brown, Raymond Edward 226.2 BRO narritives preparing for the Birth of Jesus : Matthew 1 and Luke 1 A crisis of truth - the attack on faith, morality and mission in Martin, Ralph 282.09 MAR the Catholic Church A crown of glory : a biblical view of aging Dulin, Rachel Zohar 261.834 DUL A danger to the State : An historical novel Trower, Philip 823.914 TRO A heart for Europe : the lives of Emporer Charles and Bogle, James 943.6044 BOG Empress Zita of Austria-Hungary A helping hand : A reflection guide for the divorced, Horstman, James L. -

A Pope of Their Own

Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church UPPSALA STUDIES IN CHURCH HISTORY 1 About the series Uppsala Studies in Church History is a series that is published in the Department of Theology, Uppsala University. The series includes works in both English and Swedish. The volumes are available open-access and only published in digital form. For a list of available titles, see end of the book. About the author Magnus Lundberg is Professor of Church and Mission Studies and Acting Professor of Church History at Uppsala University. He specializes in early modern and modern church and mission history with focus on colonial Latin America. Among his monographs are Mission and Ecstasy: Contemplative Women and Salvation in Colonial Spanish America and the Philippines (2015) and Church Life between the Metropolitan and the Local: Parishes, Parishioners and Parish Priests in Seventeenth-Century Mexico (2011). Personal web site: www.magnuslundberg.net Uppsala Studies in Church History 1 Magnus Lundberg A Pope of their Own El Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church Lundberg, Magnus. A Pope of Their Own: Palmar de Troya and the Palmarian Church. Uppsala Studies in Church History 1.Uppsala: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, 2017. ISBN 978-91-984129-0-1 Editor’s address: Uppsala University, Department of Theology, Church History, Box 511, SE-751 20 UPPSALA, Sweden. E-mail: [email protected]. Contents Preface 1 1. Introduction 11 The Religio-Political Context 12 Early Apparitions at El Palmar de Troya 15 Clemente Domínguez and Manuel Alonso 19 2. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

What Is an Apostolic Exhortation? It's a Papal Document That Exhorts

‘Evangelii Gaudium’ and ‘Laudato Si’ All creation “groans in travail” (Rom 8:22) How are we called to a deeper conversion? What is an apostolic exhortation? A papal document that encourages the faithful to implement a particular aspect of the Church’s life and teaching. What is an encyclical? A part of the ordinary magisterium (teaching authority) of the Church Evangelii Gaudium (English: The Joy of the Gospel) is a 2013 apostolic exhortation by Pope Francis on "the church's primary mission of evangelization in the modern world." Evangelii Gaudium What is Pope Francis’ main message in Evangelii Gaudium? The principal theme involves the need for a joyful proclamation of the Gospel to the entire world. “…an Apostolic Exhortation written around the theme of Christian joy in order that the Church may rediscover the original source of evangelisation in the contemporary world” In Evangelii Gaudium Pope Francis’ expresses: Concern that the Church is becoming more judgmental than merciful. He wants a Church that has the outgoing spirit of the pilgrim, as opposed to a Church closed in on itself, languishing in ‘institutional inertia’ He worries that some Catholics have become too attached to the external forms of the faith, while their hearts have grown cold. 6 insights provided by Pope Francis, in EG: 1 God’s inexhaustible mercy. 2 The way of beauty. 3 The ‘revolution of tenderness.’ 4 Humility before Scripture. 5 The wounds of Christ. 6 ‘Faith is always a cross.’ God’s inexhaustible mercy. We are called to renew our commitment to mercy as an external work “The Eucharist, although it is the fullness of sacramental life, is not a prize for the perfect but a powerful medicine and nourishment for the weak.” The way of beauty. -

Events of the Reformation Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution

May 20, 2018 Events of the Reformation Protestants and Roman Catholics agree on first 5 centuries. What changed? Why did some in the Church want reform by the 16th century? Outline Why the Reformation? 1. Church becomes powerful institution. 2. Additional teaching and practices were added. 3. People begin questioning the Church. 4. Martin Luther’s protest. Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution Evidence of Rome’s power grab • In 2nd century we see bishops over regions; people looked to them for guidance. • Around 195AD there was dispute over which day to celebrate Passover (14th Nissan vs. Sunday) • Polycarp said 14th Nissan, but now Victor (Bishop of Rome) liked Sunday. • A council was convened to decide, and they decided on Sunday. • But bishops of Asia continued the Passover on 14th Nissan. • Eusebius wrote what happened next: “Thereupon Victor, who presided over the church at Rome, immediately attempted to cut off from the common unity the parishes of all Asia, with the churches that agreed with them, as heterodox [heretics]; and he wrote letters and declared all the brethren there wholly excommunicate.” (Eus., Hist. eccl. 5.24.9) Everyone started looking to Rome to settle disputes • Rome was always ending up on the winning side in their handling of controversial topics. 1 • So through a combination of the fact that Rome was the most important city in the ancient world and its bishop was always right doctrinally then everyone started looking to Rome. • So Rome took that power and developed it into the Roman Catholic Church by the 600s. Church granted power to rule • Constantine gave the pope power to rule over Italy, Jerusalem, Constantinople and Alexandria. -

Parish Administrative Manual

Parish Administrative Manual Diocese of Bridgeport March 2021 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS I INTRODUCTION AND PURPOSE OF THE MANUAL………………………. 8 1. Calendar 2. Overview 3. Distribution 4. Parish Community II OFFICE OF THE BISHOP……………………………………………………………... 11 1. Overview 2. Calendar Requests for Bishop 2.1 Liturgical Celebrations 2.2 Non-Liturgical Events 3. Pastoral Year Calendar 4. Confirmation 4.1 Process III OFFICE OF THE CHANCELLOR…………………………………………………….. 14 1. Overview 2. Mass Census 3. Annual Statistical Summary 4. Official Catholic Directory 4.1 Tax-exempt Status 4.2 Public Charity Organizations IV SAFE ENVIRONMENT PROCESS………………………………………………….. 17 1. Overview 2. Reporting Suspected Abuse of a Minor or Vulnerable Adult 3. VIRTUS® Database 4. VIRTUS® Training and Requirements V EMPLOYMENT AND PERSONNEL PROCESSES……………………………. 20 1. Overview 2. Personnel Action Form Parish Employment Parish Administrative Manual Diocese of Bridgeport Issued March 2021 The entire contents of this Parish Administrative Manual © 2021 The Bridgeport Roman Catholic Diocesan Corporation. All rights reserved. 5 VI PARISH GOVERNANCE AND LEGAL ADMINISTRATION……………… 22 1. Overview 2. Religious Corporations 2.1 By-laws of the Corporation 2.2 Corporation Paperwork and Annual Meetings 3. Consultative Councils 3.1 Trustees 3.2 Finance Council 3.3 Pastoral Council 4. Leases 4.1 Lease Consent 4.2 Holy See Approval Process 5. Records 5.1 ParishSOFT 5.2 Sacramental Records 5.3 Parish Records 6. Tribunal VII FINANCE AND BUDGETING……………………………………………………… 31 1. Overview 2. Summary of Financial Accountability and Transparency 3. Reporting Timelines VIII FACILITIES AND OPERATIONS…………………………………………………… 33 1. Overview 2. Catholic Mutual Coverage Program and Assessment 3. Renovation of Sacred Space, Capital Improvements and Repairs 3.1 Diocesan Building and Sacred Arts Commission 3.2 Approval Process 4. -

Integrating Ecology and Justice: the New Papal Encyclical by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim

Feature Integrating Ecology and Justice: The New Papal Encyclical by Mary Evelyn Tucker and John Grim Mat McDermott Una Terra Una Famiglia Humana, One Earth One Family climate march in Vatican City in June 2015. In Brief In June of 2015, Pope Francis released the first encyclical on ecology. The Pope’s message highlights “integral ecology,” intrinsically linking ecological integrity and social justice. While the encyclical notes the statements of prior Popes and Bishops on the environment, Pope Francis has departed from earlier biblical language describing the domination of nature. Instead, he expresses a broader understanding of the beauty and complexity of nature, on which humans fundamentally depend. With “integral ecology” he underscores this connection of humans to the natural environment. This perspective shifts the climate debate to one of a human change of consciousness and conscience. As such, the encyclical has the potential to bring about a tipping point in the global community regarding the climate debate, not merely among Christians, but to all those attending to this moral call to action. 38 | Solutions | July-August 2015 | www.thesolutionsjournal.org n June 18, 2015 Pope Francis thinking. By drawing on and develop- We can compare Pope Francis’ released Laudato Si, the first ing the work of earlier theologians and thinking to the writing of Pope John encyclical in the history of ethicists, this encyclical makes explicit Paul II, who himself builds on Pope O Rerum the Catholic Church on ecology. An the links between social justice and Leo XIII’s progressive encyclical encyclical is the highest-level teaching eco-justice.1 Novarum on workers’ rights in 1891. -

THE CORE THEMES of the ENCYCLICAL FRATELLI TUTTI St

THE CORE THEMES OF THE ENCYCLICAL FRATELLI TUTTI St. John Lateran, 15 November 2020 Card. GIANFRANCO RAVASI Preamble Let us begin from a spiritual account drawn from Tibetan Buddhism, a different world from that of the encyclical, but significant nonetheless. A man walks alone on a desert track that dissolves into the distance on the horizon. He suddenly realises that there is another being, difficult to make out, on the same path. It may be a beast that inhabits these deserted spaces; the traveller’s heart beats faster and faster out of fear, as the wilderness does not offer any shelter or help, so he must continue to walk. As he advances, he discerns the profile: a man’s. However, fear does not leave him; in fact, that man could be a fierce bandit. He has no choice but to go on, as the fear of an assault grips his soul. The traveller no longer has the courage to look up. He can hear the other man’s steps approaching. The two men are now face to face: he looks up and stares at the person before him. In his surprise he cries out: “This is my brother whom I haven’t seen for many years!” We wish to refer to this ancient parable from a different religion and culture at the beginning of this presentation to show that the yearning pervading Pope Francis’s new encyclical Fratelli tutti is an essential component of the spiritual breadth of all humanity. In fact, we find a few unexpected “secular” quotations in the text, such as the 1962 album Samba da Bênção by Brazilian poet and musician Vinicius de Moraes (1913-1980) in which he sang: “Life, for all its confrontations, is the art of encounter” (n. -

The Holy See

The Holy See POST-SYNODAL APOSTOLIC EXHORTATION ECCLESIA IN ASIA OF THE HOLY FATHER JOHN PAUL II TO THE BISHOPS, PRIESTS AND DEACONS, MEN AND WOMEN IN THE CONSECRATED LIFE AND ALL THE LAY FAITHFUL ON JESUS CHRIST THE SAVIOUR AND HIS MISSION OF LOVE AND SERVICE IN ASIA: "...THAT THEY MAY HAVE LIFE, AND HAVE IT ABUNDANTLY" (Jn 10:10) INTRODUCTION The Marvel of God's Plan in Asia1. The Church in Asia sings the praises of the "God of salvation" (Ps 68:20) for choosing to initiate his saving plan on Asian soil, through men and women of that continent. It was in fact in Asia that God revealed and fulfilled his saving purpose from the beginning. He guided the patriarchs (cf. Gen 12) and called Moses to lead his people to freedom (cf. Ex 3:10). He spoke to his chosen people through many prophets, judges, kings and valiant women of faith. In "the fullness of time" (Gal 4:4), he sent his only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ the Saviour, who took flesh as an Asian! Exulting in the goodness of the continent's peoples, cultures, and religious vitality, and conscious at the same time of the unique gift of faith which she has received for the good of all, the Church in Asia cannot cease to proclaim: "Give thanks to the Lord for he is good, for his love endures for ever" (Ps 118:1). Because Jesus was born, lived, died and rose from the dead in the Holy Land, that small portion of Western Asia became a land of promise and hope for all mankind. -

5 How Did Nationalism Lead to a United Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815

#5 How did nationalism lead to a united Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815 • Italy had been divided up • Controlled by ruling families of Austria, France & Spain • Secretive group of revolutionaries formed in S. Italy – inspired by French Rev. 1848 • Nationalistic feelings were intensifying– throughout the 8 Italian city-states • Revolts were led by Giuseppe Mazzini – returned from exile • Leader of the “Young Italy” movement – dedicated to securing “for Italy Unity, Independence & Liberty” These Revolts Failed • Looked to Kingdom of Sardinia to rule a unified Italy – agreed they would rather have a unified Italy with a monarch than a lot of foreign powers ruling over separate states • “Risorgimento” Count Cavour & King Victor Emmanuel II • Wanted to unify Italy – make Piedmont- Sardinia the model for unification • Began public works, building projects, political reform • Next step -- get Austria out of the Italian Peninsula • Outbreak of Crimean War -- France & Britain on one side, Russia on the other • Piedmont-Sardinia saw a chance to earn some respect and make a name for itself • They were victorious and Sardinia was able to attend the peace conference. As a result of this, Piedmont- Sardinia gained the support of Napoleon III. Giuseppe Garibaldi • Italian Nationalist • Invaded S. Italy with his followers, the Red Shirts • Also supported King Victor Emmanuel – Piedmont Sardinia was only nation capable of defeating Austria • Aided by Sardinia – Cavour gave firearms to Garibaldi • Guerrilla warfare (hit & run tactics) Unified Italy • Constitutional monarchy was established – Under King Victor Emmanuel • Rome – new capital • Pope went into “exile” Garibaldi And Victor Emmanuel "Right Leg in the Boot at Last" Problems of Unification • Inexperience in self- government • Tradition of regional independence • Large part of population was illiterate • Lots of debt • Had to build an infrastructure • Severe economic & cultural divisions • (S – poor, N – more industrialized) • Centralized state, but weak Independence • Lots of people left for the U.S.