Life and Works of Saint Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beware of False Shepherds, Warhs Hem. Cardinal

Member of Audit Bureau of Circulations Principals in Pallium Ceremony i * BEWARE OF FALSE SHEPHERDS, % WARHS HEM. CARDINAL STRITCH Contonto Copjrrighted by the Catholic Preas Society, Inc. 1946— Pemiosion to reproduce, Except on Articles Otherwise Marke^ given After 12 M. Friday Following Issue Traces Catastrophes DENVER OONOLIC Of Modern Society To Godless Leaders I ^ G I S T E R Sermon al Pallium Ceremony in Denver Cathe The National Catholic Welfare Conference News Service Supplies The Denver Catholic Register. We dral Shows How Archbishop Shares in Have Also the International Nows Service (Wire and Mail), a Large Special Service, Seven Smaller Services, Photo Features, and Wide World Photos. (3 cents per copy) True Pastoral Office VOL. XU. No. 35. DENVER, COLO., THURSDAY, A PR IL 25, 1946. $1 PER YEAR Beware of false shepherds who scoff at God, call morality a mere human convention, and use tyranny and persecution as their staff. There is more than a mere state ment of truth in the words of Christ: “I am the Good Shep Official Translation of Bulls herd.” There is a challenge. Other shepherds offer to lead men through life but lead men astray. Christ is the only shepherd. Faithfully He leads men to God. This striking comparison of shepherds is the theme Erecting Archdiocese Is Given of the sermon by H. Em. Cardinal Samuel A. Stritch of Chicago in the Solemn Pon + ' + + tifical Mass in the Deliver Ca An official translation of the PERPETUAL MEMORY OF THE rate, first of all, the Diocese of thedral this Thursday morning, Papal Bulls setting up the Arch EVENT Denver, together with its clergy April 25, at which the sacred pal diocese of Denver in 1941 was The things that seem to be more and people, from the Province of lium is being conferred upon Arch Bishop Lauds released this week by the Most helpful in procuring the greater Santa Fe. -

Lent/Easter Newsletter

New Camaldoli Hermitage LENT/EASTER 2021 New Wineskins And no one puts new wine into old wineskins. If he does, the new wine will burst the skins and it will be spilled, and the skins will be destroyed. – Luke 5:37 62475 Highway 1, Big Sur, CA 93920 • 831 667 2456 • www.contemplation.com LENT/EASTER 2021 Community as an Ecosystem and Energy In This Issue Prior Cyprian Consiglio, OSB Cam. 2 Community as an Ecosystem and Energy I attended the Workshop for Prioresses and Abbots (and Prior Cyprian Consiglio, OSB Cam. Priors!) some years back, shortly after I had assumed the mantle of leadership here at New Camaldoli. The work- 4 Contemplative Renewal and New Monasticism shop was entitled “Leadership in a Complicated Rapidly Fr. Adam Bucko Changing World.” It was filled with the best advice I have 6 Camaldolese Charism Wine for New Wineskins gotten about being the prior of this community, and Andrea Seitz, Oblate, OSB Cam. phrases from it continu- ally come to my mind 7 Bede, Bruno, and New Consciousness when I am thinking Dorothea Derickson about “the big picture” here at the Hermitage 9 New Wineskins Retreat and of the future of reli- Helena Chan, Oblate, OSB Cam. gious life in general. 10 Renewal of Heart and Soul Fr. Steve Coffey, OSB Cam. The presenters first offered us two images: 11 What the Monks Are Reading one could see a com- munity either as a 11 Activities and Visitors fortress or as an eco- system. A fortress is an institution, built on a high. -

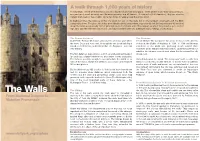

The Walls but on the Rampart Underneath and the Ditch Surrounding Them

A walk through 1,900 years of history The Bar Walls of York are the finest and most complete of any town in England. There are five main “bars” (big gateways), one postern (a small gateway) one Victorian gateway, and 45 towers. At two miles (3.4 kilometres), they are also the longest town walls in the country. Allow two hours to walk around the entire circuit. In medieval times the defence of the city relied not just on the walls but on the rampart underneath and the ditch surrounding them. The ditch, which has been filled in almost everywhere, was once 60 feet (18.3m) wide and 10 feet (3m) deep! The Walls are generally 13 feet (4m) high and 6 feet (1.8m) wide. The rampart on which they stand is up to 30 feet high (9m) and 100 feet (30m) wide and conceals the earlier defences built by Romans, Vikings and Normans. The Roman defences The Normans In AD71 the Roman 9th Legion arrived at the strategic spot where It took William The Conqueror two years to move north after his the rivers Ouse and Foss met. They quickly set about building a victory at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In 1068 anti-Norman sound set of defences, as the local tribe –the Brigantes – were not sentiment in the north was gathering steam around York. very friendly. However, when William marched north to quell the potential for rebellion his advance caused such alarm that he entered the city The first defences were simple: a ditch, an embankment made of unopposed. -

Profession Class of 2020 Survey

January 2021 Women and Men Professing Perpetual Vows in Religious Life: The Profession Class of 2020 Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate Georgetown University Washington, DC Women and Men Professing Perpetual Vows in Religious Life: The Profession Class of 2020 A Report to the Secretariat of Clergy, Consecrated Life and Vocations United States Conference of Catholic Bishops January 2021 Thu T. Do, LHC, Ph.D. Thomas P. Gaunt, SJ, Ph.D. Table of Contents Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................... 2 Major Findings ................................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 6 Institutes Reporting Perpetual Professions .................................................................................... 7 Age of Professed ............................................................................................................................. 8 Country of Birth and Age at Entry to the United States ................................................................. 9 Race and Ethnic Background......................................................................................................... 10 Family Background ....................................................................................................................... -

Anathemas and Fr John Shaw

ANATHEMAS AND FR. JOHN SHAW By Vladimir Moss The Orthodox world was shocked when, in 1965, Pope Paul VI and Patriarch Athenagoras “lifted the anathemas” on their churches. Metropolitan Philaret led the True Orthodox in protesting that this simply could not be done. The anathemas on the Filioque and other Papist heresies were eternally valid, for falsehood remains falsehood for ever; and as long as the Papists confessed these heresies, they fell under the anathemas. The essential point is this: if an anathema expresses truth, and the bishops who pronounce it are true, then it has power “to the ages of ages”, and nobody can lift it, because it is pronounced not only by the earthly Church, but also by the Heavenly Church, in accordance with the word of the Lord: “Whatever ye [the apostles and their successors] shall bind on earth shall be bound in heaven” (Matthew 18.18). However, following in the footsteps of Athenagoras, we now have a man who thinks he can lift anathemas: Fr. John Shaw. Or rather, Fr. John does not pretend to lift them (that would be a truly Herculean task for a mere priest!). He either (in the case of Patriarch Tikhon and the anathema on the Bolsheviks of 1918) says that a patriarch has lifted it, or (in the case of the ROCOR's anathema against ecumenism of 1983) does something even less plausible: he says it never really happened! The Anathema of 1918 Let us take the first case. On January 19, 1918 Patriarch Tikhon anathematised the Bolsheviks in the following words: “By the power given to Us by God, we forbid you to approach the Mysteries of Christ, we anathematise you, if only you bear Christian names and although by birth you belong to the Orthodox Church. -

The Saint Lazarus Chronicle Under the Protection of the Royal House of France

The Saint Lazarus Chronicle Under the protection of the Royal House of France Spring 2016 Commandeur Thierry de Villejust, Grand Prior “Vers l'avant!” Knights, Dames and Confrères Grand Prior, Commandeur Thierry de Villejust; H.R.H. Prince Charles-Philippe Marie Louis of Orléans, Duke of An- jou and , Grand Master Emeritus; and Commandeur Bruce Sebree at the Chapter General in Rome As our wonderfully moving sojourn at the Order’s Chapter General in Rome now settles into inspiring memories, we must take stock of our tasks and talents as the next three years will be particularly important for the Order. Internationally, we march to- wards achieving canonical status as an Association of the Faithful, which several of our Grand Priories have already attained na- tionally. We must continue to work hard to grow our order. We must also do more to spread our message of hope, by helping those who are lost or in need. Yes, our work is fun and we are energized by our mission of mercy! So let’s give thanks for our growth in spirit, in numbers, and in our contributions to making a better world. Let’s also rejoice that our Grand Mas- ter H. E. Jan Count Dobrzenský z Dobrzenicz was admitted to the Pontifical Equestrian Order of St Gregory the Great in the rank of Knight Commander on 10 December 2016 (See Page 2 story: “St. Lazarus Grand Master, Knighted by the Pope). This was bestowed upon him for doing what he loves: pursuing justice and mercy to the call of Atavis et Armis! Commander Thierry de Villejust, Grand Prior St. -

Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion

A (New) Ecclesiology of the Anglican Communion: Rediscovering the Radical and Transnational Nature of the Anglican Communion Guillermo René Cavieses Araya Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Faculty of Arts School of Philosophy, Religion and History of Science February 2019 1 The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from this thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2019 The University of Leeds and Guillermo René Cavieses Araya The right of Guillermo René Cavieses Araya to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by Guillermo René Cavieses Araya in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. 2 Acknowledgements No man is an island, and neither is his work. This thesis would not have been possible without the contribution of a lot of people, going a long way back. So, let’s start at the beginning. Mum, thank you for teaching me that it was OK for me to dream of working for a circus when I was little, so long as I first went to University to get a degree on it. Dad, thanks for teaching me the value of books and a solid right hook. To my other Dad, thank you for teaching me the virtue of patience (yes, I know, I am still working on that one). -

XIX.—Reginald, Bishop of Bath (Hjjfugi); His Episcopate, and His Share in the Building of the Church of Wells. by the Rev. C. M

XIX.—Reginald, bishop of Bath (HJJfUgi); his episcopate, and his share in the building of the church of Wells. By the Rev. C. M. CHURCH, M.A., F.8.A., Sub-dean and Canon Residentiary of Wells. Read June 10, 1886. I VENTURE to think that bishop Eeginald Fitzjocelin deserves a place of higher honour in the history of the diocese, and of the fabric of the church of Wells, than has hitherto been accorded to him. His memory has been obscured by the traditionary fame of bishop Robert as the "author," and of bishop Jocelin as the "finisher," of the church of Wells; and the importance of his episcopate as a connecting link in the work of these two master-builders has been comparatively overlooked. The only authorities followed for the history of his episcopate have been the work of the Canon of Wells, printed by Wharton, in his Anglia Sacra, 1691, and bishop Godwin, in his Catalogue of the Bishops of England, 1601—1616. But Wharton, in his notes to the text of his author, comments on the scanty notice of bishop Reginald ;a and Archer, our local chronicler, complains of the unworthy treatment bishop Reginald had received from Godwin, also a canon of his own cathedral church.b a Reginaldi gesta historicus noster brevius quam pro viri dignitate enarravit. Wharton, Anglia Sacra, i. 871. b Historicus noster et post eum Godwinus nimis breviter gesta Reginaldi perstringunt quae pro egregii viri dignitate narrationem magis applicatam de Canonicis istis Wellensibus merita sunt. Archer, Ghronicon Wellense, sive annales Ecclesiae Cathedralis Wellensis, p. -

Events of the Reformation Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution

May 20, 2018 Events of the Reformation Protestants and Roman Catholics agree on first 5 centuries. What changed? Why did some in the Church want reform by the 16th century? Outline Why the Reformation? 1. Church becomes powerful institution. 2. Additional teaching and practices were added. 3. People begin questioning the Church. 4. Martin Luther’s protest. Part 1 – Church Becomes Powerful Institution Evidence of Rome’s power grab • In 2nd century we see bishops over regions; people looked to them for guidance. • Around 195AD there was dispute over which day to celebrate Passover (14th Nissan vs. Sunday) • Polycarp said 14th Nissan, but now Victor (Bishop of Rome) liked Sunday. • A council was convened to decide, and they decided on Sunday. • But bishops of Asia continued the Passover on 14th Nissan. • Eusebius wrote what happened next: “Thereupon Victor, who presided over the church at Rome, immediately attempted to cut off from the common unity the parishes of all Asia, with the churches that agreed with them, as heterodox [heretics]; and he wrote letters and declared all the brethren there wholly excommunicate.” (Eus., Hist. eccl. 5.24.9) Everyone started looking to Rome to settle disputes • Rome was always ending up on the winning side in their handling of controversial topics. 1 • So through a combination of the fact that Rome was the most important city in the ancient world and its bishop was always right doctrinally then everyone started looking to Rome. • So Rome took that power and developed it into the Roman Catholic Church by the 600s. Church granted power to rule • Constantine gave the pope power to rule over Italy, Jerusalem, Constantinople and Alexandria. -

A Community of Monks Or Nuns, Ruled by an Abbot Or Abbess. Usually Founded by a Monastic Order

Abbey - a community of monks or nuns, ruled by an abbot or abbess. Usually founded by a monastic order. Abbeys oftne owe some form of feudal obligation to a lord or higher organization. They are normally self-contained. Abjuration - renunciation, under oath, of heresy to the Christian faith, made by a Christian wishing to be reconciled with the Church. Accidie - term used in ascetical literature for spiritual sloth, boredom, and discouragement. Acolyte - a clerk in minor orders whose particular duty was the service of the altar. Advocate - lay protector and legal representative of a monastery. Advowson - the right of nominating or presenting a clergyman to a vacant living. Agistment - a Church rate, or tithe, charged on pasture land. Aisle - lateral division of the nave or chancel of a church. Alb - a full-length white linen garment, with sleeves and girdle, worn by the celebrant at mass under a chasuble. Almoner - officer of a monastery entrusted with dispensing alms to the poor and sick. Almonry - place from which alms were dispensed to the poor. Almuce - large cape, often with attached hood, of cloth turned down over the shoulders and lined with fur. Doctors of Divinity and canons wore it lined with gray fur. Cape was edged with little Ambulatory - aisle leading round an apse, usually encircling the choir of a church. Amice - a square of white linen, folded diagonally, worn by the celebrant priest, on the head or about the neck and shoulders. Anathema - condemnation of heretics, similar to major excommunication. It inflicts the penalty of complete exclusion from Christian society. -

Inmate Release Report Snapshot Taken: 9/28/2021 6:00:10 AM

Inmate Release Report Snapshot taken: 9/28/2021 6:00:10 AM Projected Release Date Booking No Last Name First Name 9/29/2021 6090989 ALMEDA JONATHAN 9/29/2021 6249749 CAMACHO VICTOR 9/29/2021 6224278 HARTE GREGORY 9/29/2021 6251673 PILOTIN MANUEL 9/29/2021 6185574 PURYEAR KORY 9/29/2021 6142736 REYES GERARDO 9/30/2021 5880910 ADAMS YOLANDA 9/30/2021 6250719 AREVALO JOSE 9/30/2021 6226836 CALDERON ISAIAH 9/30/2021 6059780 ESTRADA CHRISTOPHER 9/30/2021 6128887 GONZALEZ JUAN 9/30/2021 6086264 OROZCO FRANCISCO 9/30/2021 6243426 TOBIAS BENJAMIN 10/1/2021 6211938 ALAS CHRISTOPHER 10/1/2021 6085586 ALVARADO BRYANT 10/1/2021 6164249 CASTILLO LUIS 10/1/2021 6254189 CASTRO JAYCEE 10/1/2021 6221163 CUBIAS ERICK 10/1/2021 6245513 MYERS ALBERT 10/1/2021 6084670 ORTIZ MATTHEW 10/1/2021 6085145 SANCHEZ ARAFAT 10/1/2021 6241199 SANCHEZ JORGE 10/1/2021 6085431 TORRES MANLIO 10/2/2021 6250453 ALVAREZ JOHNNY 10/2/2021 6241709 ESTRADA JOSE 10/2/2021 6242141 HUFF ADAM 10/2/2021 6254134 MEJIA GERSON 10/2/2021 6242125 ROBLES GUSTAVO 10/2/2021 6250718 RODRIGUEZ RAFAEL 10/2/2021 6225488 SANCHEZ NARCISO 10/2/2021 6248409 SOLIS PAUL 10/2/2021 6218628 VALDEZ EDDIE 10/2/2021 6159119 VERNON JIMMY 10/3/2021 6212939 ADAMS LANCE 10/3/2021 6239546 BELL JACKSON 10/3/2021 6222552 BRIDGES DAVID 10/3/2021 6245307 CERVANTES FRANCISCO 10/3/2021 6252321 FARAMAZOV ARTUR 10/3/2021 6251594 GOLDEN DAMON 10/3/2021 6242465 GOSSETT KAMERA 10/3/2021 6237998 MOLINA ANTONIO 10/3/2021 6028640 MORALES CHRISTOPHER 10/3/2021 6088136 ROBINSON MARK 10/3/2021 6033818 ROJO CHRISTOPHER 10/3/2021 -

Carroll-March-MEMHS-Meeting-1

Dear members of MEMHS, I’ve attached a chapter of my dissertation for our discussion on March 23. I am considering either revising the chapter for a book manuscript or dividing it up into several articles. Given my current career trajectory at the Sheridan Center, I am unsure which of these publication formats makes the most sense for me professionally, so I invite feedback on the paper’s potential in either of these formats (along with any other feedback you may wish to provide). I look forward to discussing the paper, and the project as a whole, with you all next Tuesday. Sincerely, Charlie Carroll CHAPTER 4 TO KNOW THE ORDINANCES OF THE HEAVENS: PREACHING MANLINESS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PARIS When Guillaume d’Auvergne, bishop of Paris, began his sermon on the Vigil of All Saints in 1230, his words likely echoed around an empty nave. Looking up from the pulpit, he would have glanced out at a much-depleted audience, an audience likely comprised largely of students and clergy.1 This was more than a year and a half since a drunken brawl between a band of students and an innkeeper over the price of wine led to an immediate strike of students and masters, thereby endangering both the establishment of the University and the economy of the city of Paris. The dispute, which had begun in the faubourg of Saint-Marcel on Shrove Tuesday in 1229, had quickly escalated from pulling hair and striking blows to, on the following day, an all-out street riot with students armed with wooden clubs.2 The bishop, along with the prior of Saint-Marcel and 1 The sermon is included in Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS nouv.