Buonarroti and His International Secret Societies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unification of Italy and Germany

EUROPEAN HISTORY Unit 10 The Unification of Italy and Germany Form 4 Unit 10.1 - The Unification of Italy Revolution in Naples, 1848 Map of Italy before unification. Revolution in Rome, 1848 Flag of the Kingdom of Italy, 1861-1946 1. The Early Phase of the Italian Risorgimento, 1815-1848 The settlements reached in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna had restored Austrian domination over the Italian peninsula but had left Italy completely fragmented in a number of small states. The strongest and most progressive Italian state was the Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont in north-western Italy. At the Congress of Vienna this state had received the lands of the former Republic of Genoa. This acquisition helped Sardinia-Piedmont expand her merchant fleet and trade centred in the port of Genoa. There were three major obstacles to unity at the time of the Congress of Vienna: The Austrians occupied Lombardy and Venetia in Northern Italy. The Papal States controlled Central Italy. The other Italian states had maintained their independence: the Kingdom of Sardinia, also called Piedmont-Sardinia, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (ruler by the Bourbon dynasty) and the Duchies of Tuscany, Parma and Modena (ruled by relatives of the Austrian Habsburgs). During the 1820s the Carbonari secret society tried to organize revolts in Palermo and Naples but with very little success, mainly because the Carbonari did not have the support of the peasants. Then came Giuseppe Mazzini, a patriotic writer who set up a national revolutionary movement known as Young Italy (1831). Mazzini was in favour of a united republic. -

The Unification of Italy

New Dorp High School Social Studies Department AP Global Mr. Hubbs & Mrs. Zoleo The Unification of Italy While nationalism destroyed empires, it also built nations. Italy was one of the countries to form from the territories of the crumbling empires. After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Austria ruled the Italian provinces of Venetia and Lombardy in the north, and several small states. In the south, the Spanish Bourbon family ruled the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies. Nevertheless, between 1815 and 1848, increasing numbers of Italians were no longer content to live under foreign rulers. Amid growing discontent, two leaders appeared—one was idealistic, the other practical. They had different personalities and pursued different goals. But each contributed to the Unification of Italy. The Movement for Unity Begins In 1832, an idealistic 26-year-old Italian named Guiseppe Mazzini organized a nationalist group called, Young Italy. Similarly, youth were the leaders and custodians of the nineteenth century nationalist movements. The Napoleonic Wars were lead principally by younger men. Napoleon was 35 years of age when crowned Emperor. As nationalism spread across Europe the pattern continued. People over 40 were excluded from Mazzini's organization. During the violent year of 1848, revolts broke out in eight states on the Italian Peninsula. Mazzini briefly headed a republican government in Rome. He believed that nation-states were the best hope for social justice, democracy, and peace in Europe. However, the 1848 rebellions failed in Italy as they did elsewhere in Europe. The foreign rulers of the Italian states drove Mazzini and other nationalist leaders into exile. -

Marx, Bakunin, and the Question of Authoritarianism - David Adam

Marx, Bakunin, and the question of authoritarianism - David Adam Historically, Bakunin’s criticism of Marx’s “authoritarian” aims has tended to overshadow Marx’s critique of Bakunin’s “authoritarian” aims. This is in large part due to the fact that mainstream anarchism and Marxism have been polarized over a myth—that of Marx’s authoritarian statism—which they both share. Thus, the conflict in the First International is directly identified with a disagreement over anti-authoritarian principles, and Marx’s hostility toward Bakunin is said to stem from his rejection of these principles, his vanguardism, etc. Anarchism, not without justification, posits itself as the “libertarian” alternative to the “authoritarianism” of mainstream Marxism. Because of this, nothing could be easier than to see the famous conflict between the pioneering theorists of these movements—Bakunin and Marx—as a conflict between absolute liberty and authoritarianism. This essay will bring this narrative into question. It will not do this by making grand pronouncements about Anarchism and Marxism in the abstract, but simply by assembling some often neglected evidence. Bakunin’s ideas about revolutionary organization lie at the heart of this investigation. Political Philosophy We will begin by looking at some differences in political philosophy between Marx and Bakunin that will inform our understanding of their organizational disputes. In Bakunin, Marx criticized first and foremost what he saw as a modernized version of Proudhon’s doctrinaire attitude towards politics—the -

Mcq Drill for Practice—Test Yourself (Answer Key at the Last)

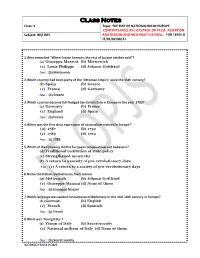

Class Notes Class: X Topic: THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN EUROPE CONTENTS-MCQ ,FILL UPS,TRUE OR FALSE, ASSERTION Subject: HISTORY AND REASON AND MCQ PRACTICE DRILL… FOR TERM-I/ JT/01/02/08/21 1.Who remarked “When France Sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold”? (a) Giuseppe Mazzini (b) Metternich (c) Louis Philippe (d) Johann Gottfried Ans : (b) Metternich 2.Which country had been party of the ‘Ottoman Empire’ since the 15th century? (b) Spain (b) Greece (c) France (d) Germany Ans : (b) Greece 3.Which country became full-fledged territorial state in Europe in the year 1789? (c) Germany (b) France (c) England (d) Spain Ans : (b) France 4.When was the first clear expression of nationalism noticed in Europe? (a) 1787 (b) 1759 (c) 1789 (d) 1769 Ans : (c) 1789 5.Which of the following did the European conservatives not believe in? (d) Traditional institution of state policy (e) Strengthened monarchy (f) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days Ans : (c) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days 6.Name the Italian revolutionary from Genoa. (g) Metternich (b) Johann Gottfried (c) Giuseppe Mazzini (d) None of these Ans : (c) Giuseppe Mazzini 7.Which language was spoken for purposes of diplomacy in the mid 18th century in Europe? (h) German (b) English (c) French (d) Spanish Ans : (c) French 8.What was ‘Young Italy’ ? (i) Vision of Italy (b) Secret society (c) National anthem of Italy (d) None of these Ans : (b) Secret society WORKED FROM HOME 9.Treaty of Constantinople recognised .......... as an independent nation. -

By Filippo Sabetti Mcgill University the MAKING of ITALY AS AN

THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE by Filippo Sabetti McGill University THE MAKING OF ITALY AS AN EXPERIMENT IN CONSTITUTIONAL CHOICE In his reflections on the history of European state-making, Charles Tilly notes that the victory of unitary principles of organiza- tion has obscured the fact, that federal principles of organization were alternative design criteria in The Formation of National States in West- ern Europe.. Centralized commonwealths emerged from the midst of autonomous, uncoordinated and lesser political structures. Tilly further reminds us that "(n)othing could be more detrimental to an understanding of this whole process than the old liberal conception of European history as the gradual creation and extension of political rights .... Far from promoting (representative) institutions, early state-makers 2 struggled against them." The unification of Italy in the nineteenth century was also a victory of centralized principles of organization but Italian state- making or Risorgimento differs from earlier European state-making in at least three respects. First, the prospects of a single political regime for the entire Italian peninsula and islands generated considerable debate about what model of government was best suited to a population that had for more than thirteen hundred years lived under separate and diverse political regimes. The system of government that emerged was the product of a conscious choice among alternative possibilities con- sidered in the formulation of the basic rules that applied to the organi- zation and conduct of Italian governance. Second, federal principles of organization were such a part of the Italian political tradition that the victory of unitary principles of organization in the making of Italy 2 failed to obscure or eclipse them completely. -

5 How Did Nationalism Lead to a United Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815

#5 How did nationalism lead to a united Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815 • Italy had been divided up • Controlled by ruling families of Austria, France & Spain • Secretive group of revolutionaries formed in S. Italy – inspired by French Rev. 1848 • Nationalistic feelings were intensifying– throughout the 8 Italian city-states • Revolts were led by Giuseppe Mazzini – returned from exile • Leader of the “Young Italy” movement – dedicated to securing “for Italy Unity, Independence & Liberty” These Revolts Failed • Looked to Kingdom of Sardinia to rule a unified Italy – agreed they would rather have a unified Italy with a monarch than a lot of foreign powers ruling over separate states • “Risorgimento” Count Cavour & King Victor Emmanuel II • Wanted to unify Italy – make Piedmont- Sardinia the model for unification • Began public works, building projects, political reform • Next step -- get Austria out of the Italian Peninsula • Outbreak of Crimean War -- France & Britain on one side, Russia on the other • Piedmont-Sardinia saw a chance to earn some respect and make a name for itself • They were victorious and Sardinia was able to attend the peace conference. As a result of this, Piedmont- Sardinia gained the support of Napoleon III. Giuseppe Garibaldi • Italian Nationalist • Invaded S. Italy with his followers, the Red Shirts • Also supported King Victor Emmanuel – Piedmont Sardinia was only nation capable of defeating Austria • Aided by Sardinia – Cavour gave firearms to Garibaldi • Guerrilla warfare (hit & run tactics) Unified Italy • Constitutional monarchy was established – Under King Victor Emmanuel • Rome – new capital • Pope went into “exile” Garibaldi And Victor Emmanuel "Right Leg in the Boot at Last" Problems of Unification • Inexperience in self- government • Tradition of regional independence • Large part of population was illiterate • Lots of debt • Had to build an infrastructure • Severe economic & cultural divisions • (S – poor, N – more industrialized) • Centralized state, but weak Independence • Lots of people left for the U.S. -

Unification of Italy 1792 to 1925 French Revolutionary Wars to Mussolini

UNIFICATION OF ITALY 1792 TO 1925 FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY WARS TO MUSSOLINI ERA SUMMARY – UNIFICATION OF ITALY Divided Italy—From the Age of Charlemagne to the 19th century, Italy was divided into northern, central and, southern kingdoms. Northern Italy was composed of independent duchies and city-states that were part of the Holy Roman Empire; the Papal States of central Italy were ruled by the Pope; and southern Italy had been ruled as an independent Kingdom since the Norman conquest of 1059. The language, culture, and government of each region developed independently so the idea of a united Italy did not gain popularity until the 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars wreaked havoc on the traditional order. Italian Unification, also known as "Risorgimento", refers to the period between 1848 and 1870 during which all the kingdoms on the Italian Peninsula were united under a single ruler. The most well-known character associated with the unification of Italy is Garibaldi, an Italian hero who fought dozens of battles for Italy and overthrew the kingdom of Sicily with a small band of patriots, but this romantic story obscures a much more complicated history. The real masterminds of Italian unity were not revolutionaries, but a group of ministers from the kingdom of Sardinia who managed to bring about an Italian political union governed by ITALY BEFORE UNIFICATION, 1792 B.C. themselves. Military expeditions played an important role in the creation of a United Italy, but so did secret societies, bribery, back-room agreements, foreign alliances, and financial opportunism. Italy and the French Revolution—The real story of the Unification of Italy began with the French conquest of Italy during the French Revolutionary Wars. -

Fair Shares for All

FAIR SHARES FOR ALL JACOBIN EGALITARIANISM IN PRACT ICE JEAN-PIERRE GROSS This study explores the egalitarian policies pursued in the provinces during the radical phase of the French Revolution, but moves away from the habit of looking at such issues in terms of the Terror alone. It challenges revisionist readings of Jacobinism that dwell on its totalitarian potential or portray it as dangerously Utopian. The mainstream Jacobin agenda held out the promise of 'fair shares' and equal opportunities for all in a private-ownership market economy. It sought to achieve social justice without jeopardising human rights and tended thus to complement, rather than undermine, the liberal, individualist programme of the Revolution. The book stresses the relevance of the 'Enlightenment legacy', the close affinities between Girondins and Montagnards, the key role played by many lesser-known figures and the moral ascendancy of Robespierre. It reassesses the basic social and economic issues at stake in the Revolution, which cannot be adequately understood solely in terms of political discourse. Past and Present Publications Fair shares for all Past and Present Publications General Editor: JOANNA INNES, Somerville College, Oxford Past and Present Publications comprise books similar in character to the articles in the journal Past and Present. Whether the volumes in the series are collections of essays - some previously published, others new studies - or mono- graphs, they encompass a wide variety of scholarly and original works primarily concerned with social, economic and cultural changes, and their causes and consequences. They will appeal to both specialists and non-specialists and will endeavour to communicate the results of historical and allied research in readable and lively form. -

Enjoy Your Visit!!!

declared war on Austria, in alliance with the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and attacked the weakened Austria in her Italian possessions. embarked to Sicily to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the But Piedmontese Army was defeated by Radetzky; Charles Albert abdicated Bourbons. Garibaldi gathered 1.089 volunteers: they were poorly armed in favor of his son Victor Emmanuel, who signed the peace treaty on 6th with dated muskets and were dressed in a minimalist uniform consisting of August 1849. Austria reoccupied Northern Italy. Sardinia wasn’t able to beat red shirts and grey trousers. On 5th May they seized two steamships, which Austria alone, so it had to look for an alliance with European powers. they renamed Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo, at Quarto, near Genoa. On 11th May they landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily; on 15th they Room 8 defeated Neapolitan troops at Calatafimi, than they conquered Palermo on PALAZZO MORIGGIA the 29th , after three days of violent clashes. Following the victory at Milazzo (29th May) they were able to control all the island. The last battle took MUSEO DEL RISORGIMENTO THE DECADE OF PREPARATION 1849-1859 place on 1st October at Volturno, where twenty-one thousand Garibaldini The Decade of Preparation 1849-1859 (Decennio defeated thirty thousand Bourbons soldiers. The feat was a success: Naples di Preparazione) took place during the last years of and Sicily were annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia by a plebiscite. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY HISTORY LABORATORY Risorgimento, ended in 1861 with the proclamation CIVIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION of the Kingdom of Italy, guided by Vittorio Emanuele Room 13-14 II. -

Giuseppe Mazzini's International Political Thought

Copyrighted Material INTRODUCTION Giuseppe Mazzini’s International Political Thought Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–72) is today largely remembered as the chief inspirer and leading political agitator of the Italian Risorgimento. Yet Mazzini was not merely an Italian patriot, and his influence reached far beyond his native country and his century. In his time, he ranked among the leading European intellectual figures, competing for public atten tion with Mikhail Bakunin and Karl Marx, John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville. According to his friend Alexander Herzen, the Russian political activist and writer, Mazzini was the “shining star” of the dem ocratic revolutions of 1848. In those days Mazzini’s reputation soared so high that even the revolution’s ensuing defeat left most of his Euro pean followers with a virtually unshakeable belief in the eventual tri umph of their cause.1 Mazzini was an original, if not very systematic, political thinker. He put forward principled arguments in support of various progressive causes, from universal suffrage and social justice to women’s enfran chisement. Perhaps most fundamentally, he argued for a reshaping of the European political order on the basis of two seminal principles: de mocracy and national selfdetermination. These claims were extremely radical in his time, when most of continental Europe was still under the rule of hereditary kingships and multinational empires such as the Habs burgs and the ottomans. Mazzini worked primarily on people’s minds and opinions, in the belief that radical political change first requires cultural and ideological transformations on which to take root. He was one of the first political agitators and public intellectuals in the contemporary sense of the term: not a solitary thinker or soldier but rather a political leader who sought popular support and participa tion. -

BUONARROTI's IDEAS on COMMUNISM and DICTATORSHIP Le Nom Seul De Buonarroti Est Une Doctrine

ARTHUR LEHNING BUONARROTI'S IDEAS ON COMMUNISM AND DICTATORSHIP Le nom seul de Buonarroti est une doctrine. Franzinetti, in ,,Le Radical", 24.9.1837. At the University of Pisa, where he studied law, Buonarroti had been acquainted with the 18th century social philosophers especially Hel- vetius, Mably, Rousseau and Morelly, who had moulded his social and political ideology. When the French Revolution broke out he was among the most courageous protagonists to defend its ideas: "J'atten- dais depuis longtemps le signal, il fut donne". In October 1789 he left his native Tuscany, "ivre de l'amour de la liberte, epris de la coura- geuse entreprise des Francais, indigne contre la tyrannie, et las de l'inquisition et des persecutions du despotisme", as he said later in his defence at Vendome. In Corsica he published an Italian paper in defence of the French Revolution, the Giornale Patriottico 1, and in November 1790 he obtained a post in the administration of the island as head of the "Bureau des domaines nationaux et du clerge". In this capacity he had to deal with the administration and sale of landed property. The rural economy of the island was based on a nearly equal distribution of very small holdings, there were hardly any labourers, and there existed a strong tradition of common interests and collective rights. In his Survey of Corsica Buonarroti wrote: "La communalite des biens semble garantir partout au pauvre le sentiment 1 The only complete copy known to exist is now in the Biblioteca Feltrinelli, Milan. Most biographical articles mention an Italian paper, l'Amico della Liberta Italiana, edited by Buonarroti in Corsica. -

Cultural Techniques

Cultural Techniques Cultural Techniques Assembling Spaces, Texts & Collectives Edited by Jörg Dünne, Kathrin Fehringer, Kristina Kuhn, and Wolfgang Struck We acknowledge support by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the Open Access Publication Fund of Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin. ISBN 978-3-11-064456-2 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-064704-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-064534-7 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110647044 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. For details go to: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020939337 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2020 Jörg Dünne, Kathrin Fehringer, Kristina Kuhn, and Wolfgang Struck, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: porpeller/iStock/Getty Images Plus Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Contents Jörg Dünne, Kathrin Fehringer, Kristina Kuhn, and Wolfgang Struck Introduction 1 Spaces Tom Ullrich Working on Barricades and Boulevards: Cultural Techniques of Revolution in Nineteenth-Century Paris 23 Jörg Dünne Cultural Techniques and Founding Fictions 47 Wolfgang Struck A Message in a Bottle 61 Gabriele Schabacher Waiting: Cultural Techniques, Media, and Infrastructures 73 Christoph Eggersglüß Orthopedics by the Roadside: Spikes and Studs as Devices of Social Normalization 87 Hannah Zindel Ballooning: Aeronautical Techniques from Montgolfier to Google 107 Texts/Bodies Bernhard Siegert Attached: The Object and the Collective 131 Michael Cuntz Monturen/montures: On Riding, Dressing, and Wearing.