Biography and the Making of Modern Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mcq Drill for Practice—Test Yourself (Answer Key at the Last)

Class Notes Class: X Topic: THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN EUROPE CONTENTS-MCQ ,FILL UPS,TRUE OR FALSE, ASSERTION Subject: HISTORY AND REASON AND MCQ PRACTICE DRILL… FOR TERM-I/ JT/01/02/08/21 1.Who remarked “When France Sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold”? (a) Giuseppe Mazzini (b) Metternich (c) Louis Philippe (d) Johann Gottfried Ans : (b) Metternich 2.Which country had been party of the ‘Ottoman Empire’ since the 15th century? (b) Spain (b) Greece (c) France (d) Germany Ans : (b) Greece 3.Which country became full-fledged territorial state in Europe in the year 1789? (c) Germany (b) France (c) England (d) Spain Ans : (b) France 4.When was the first clear expression of nationalism noticed in Europe? (a) 1787 (b) 1759 (c) 1789 (d) 1769 Ans : (c) 1789 5.Which of the following did the European conservatives not believe in? (d) Traditional institution of state policy (e) Strengthened monarchy (f) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days Ans : (c) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days 6.Name the Italian revolutionary from Genoa. (g) Metternich (b) Johann Gottfried (c) Giuseppe Mazzini (d) None of these Ans : (c) Giuseppe Mazzini 7.Which language was spoken for purposes of diplomacy in the mid 18th century in Europe? (h) German (b) English (c) French (d) Spanish Ans : (c) French 8.What was ‘Young Italy’ ? (i) Vision of Italy (b) Secret society (c) National anthem of Italy (d) None of these Ans : (b) Secret society WORKED FROM HOME 9.Treaty of Constantinople recognised .......... as an independent nation. -

5 How Did Nationalism Lead to a United Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815

#5 How did nationalism lead to a united Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815 • Italy had been divided up • Controlled by ruling families of Austria, France & Spain • Secretive group of revolutionaries formed in S. Italy – inspired by French Rev. 1848 • Nationalistic feelings were intensifying– throughout the 8 Italian city-states • Revolts were led by Giuseppe Mazzini – returned from exile • Leader of the “Young Italy” movement – dedicated to securing “for Italy Unity, Independence & Liberty” These Revolts Failed • Looked to Kingdom of Sardinia to rule a unified Italy – agreed they would rather have a unified Italy with a monarch than a lot of foreign powers ruling over separate states • “Risorgimento” Count Cavour & King Victor Emmanuel II • Wanted to unify Italy – make Piedmont- Sardinia the model for unification • Began public works, building projects, political reform • Next step -- get Austria out of the Italian Peninsula • Outbreak of Crimean War -- France & Britain on one side, Russia on the other • Piedmont-Sardinia saw a chance to earn some respect and make a name for itself • They were victorious and Sardinia was able to attend the peace conference. As a result of this, Piedmont- Sardinia gained the support of Napoleon III. Giuseppe Garibaldi • Italian Nationalist • Invaded S. Italy with his followers, the Red Shirts • Also supported King Victor Emmanuel – Piedmont Sardinia was only nation capable of defeating Austria • Aided by Sardinia – Cavour gave firearms to Garibaldi • Guerrilla warfare (hit & run tactics) Unified Italy • Constitutional monarchy was established – Under King Victor Emmanuel • Rome – new capital • Pope went into “exile” Garibaldi And Victor Emmanuel "Right Leg in the Boot at Last" Problems of Unification • Inexperience in self- government • Tradition of regional independence • Large part of population was illiterate • Lots of debt • Had to build an infrastructure • Severe economic & cultural divisions • (S – poor, N – more industrialized) • Centralized state, but weak Independence • Lots of people left for the U.S. -

Northern Italy: the Alps, Dolomites & Lombardy 2021

YOUR O.A.T. ADVENTURE TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE® Northern Italy: The Alps, Dolomites & Lombardy 2021 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 13) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Personalized Small Group Adventures on the Road Less Traveled 1 Dear Traveler, At last, the world is opening up again for curious travel lovers like you and me. And the O.A.T. Northern Italy: The Alps, Dolomites & Lombardy itinerary you’ve expressed interest in will be a wonderful way to resume the discoveries that bring us so much joy. You might soon be enjoying standout moments like these: In my mind, nothing is more idyllic than the mountainous landscapes and rural villages of Alpine Europe. To immerse myself in their pastoral traditions and everyday life, I love to explore rural communities like Teglio, a small village nestled in the Valtellina Valley. You’ll see what I mean when you experience A Day in the Life of a small, family-run farm here where you’ll have the opportunity to meet the owner, walk the grounds, lend a hand with the daily farm chores, and share a traditional meal with your hosts in the farmhouse. You’ll also get a taste for some of the other crafts in the Valley when you visit a locally-owned goat cheese producer and a water-powered mill. But the most moving stories of all were the ones I heard directly from the local people I met. You’ll meet them, too, and hear their personal experiences during a conversation with two political refugeees at a local café in Milan to discuss the deeply divisive issue of immigration in Italy. -

Pius Ix and the Change in Papal Authority in the Nineteenth Century

ABSTRACT ONE MAN’S STRUGGLE: PIUS IX AND THE CHANGE IN PAPAL AUTHORITY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Andrew Paul Dinovo This thesis examines papal authority in the nineteenth century in three sections. The first examines papal issues within the world at large, specifically those that focus on the role of the Church within the political state. The second section concentrates on the authority of Pius IX on the Italian peninsula in the mid-nineteenth century. The third and final section of the thesis focuses on the inevitable loss of the Papal States within the context of the Vatican Council of 1869-1870. Select papal encyclicals from 1859 to 1871 and the official documents of the Vatican Council of 1869-1870 are examined in light of their relevance to the change in the nature of papal authority. Supplementing these changes is a variety of seminal secondary sources from noted papal scholars. Ultimately, this thesis reveals that this change in papal authority became a point of contention within the Church in the twentieth century. ONE MAN’S STRUGGLE: PIUS IX AND THE CHANGE IN PAPAL AUTHORITY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Andrew Paul Dinovo Miami University Oxford, OH 2004 Advisor____________________________________________ Dr. Sheldon Anderson Reader_____________________________________________ Dr. Wietse de Boer Reader_____________________________________________ Dr. George Vascik Contents Section I: Introduction…………………………………………………………………….1 Section II: Primary Sources……………………………………………………………….5 Section III: Historiography……...………………………………………………………...8 Section IV: Issues of Church and State: Boniface VIII and Unam Sanctam...…………..13 Section V: The Pope in Italy: Political Papal Encyclicals….……………………………20 Section IV: The Loss of the Papal States: The Vatican Council………………...………41 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………..55 ii I. -

Enjoy Your Visit!!!

declared war on Austria, in alliance with the Papal States and the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and attacked the weakened Austria in her Italian possessions. embarked to Sicily to conquer the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, ruled by the But Piedmontese Army was defeated by Radetzky; Charles Albert abdicated Bourbons. Garibaldi gathered 1.089 volunteers: they were poorly armed in favor of his son Victor Emmanuel, who signed the peace treaty on 6th with dated muskets and were dressed in a minimalist uniform consisting of August 1849. Austria reoccupied Northern Italy. Sardinia wasn’t able to beat red shirts and grey trousers. On 5th May they seized two steamships, which Austria alone, so it had to look for an alliance with European powers. they renamed Il Piemonte and Il Lombardo, at Quarto, near Genoa. On 11th May they landed at Marsala, on the westernmost point of Sicily; on 15th they Room 8 defeated Neapolitan troops at Calatafimi, than they conquered Palermo on PALAZZO MORIGGIA the 29th , after three days of violent clashes. Following the victory at Milazzo (29th May) they were able to control all the island. The last battle took MUSEO DEL RISORGIMENTO THE DECADE OF PREPARATION 1849-1859 place on 1st October at Volturno, where twenty-one thousand Garibaldini The Decade of Preparation 1849-1859 (Decennio defeated thirty thousand Bourbons soldiers. The feat was a success: Naples di Preparazione) took place during the last years of and Sicily were annexed to the Kingdom of Sardinia by a plebiscite. MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY HISTORY LABORATORY Risorgimento, ended in 1861 with the proclamation CIVIC HISTORICAL COLLECTION of the Kingdom of Italy, guided by Vittorio Emanuele Room 13-14 II. -

Giuseppe Mazzini's International Political Thought

Copyrighted Material INTRODUCTION Giuseppe Mazzini’s International Political Thought Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–72) is today largely remembered as the chief inspirer and leading political agitator of the Italian Risorgimento. Yet Mazzini was not merely an Italian patriot, and his influence reached far beyond his native country and his century. In his time, he ranked among the leading European intellectual figures, competing for public atten tion with Mikhail Bakunin and Karl Marx, John Stuart Mill and Alexis de Tocqueville. According to his friend Alexander Herzen, the Russian political activist and writer, Mazzini was the “shining star” of the dem ocratic revolutions of 1848. In those days Mazzini’s reputation soared so high that even the revolution’s ensuing defeat left most of his Euro pean followers with a virtually unshakeable belief in the eventual tri umph of their cause.1 Mazzini was an original, if not very systematic, political thinker. He put forward principled arguments in support of various progressive causes, from universal suffrage and social justice to women’s enfran chisement. Perhaps most fundamentally, he argued for a reshaping of the European political order on the basis of two seminal principles: de mocracy and national selfdetermination. These claims were extremely radical in his time, when most of continental Europe was still under the rule of hereditary kingships and multinational empires such as the Habs burgs and the ottomans. Mazzini worked primarily on people’s minds and opinions, in the belief that radical political change first requires cultural and ideological transformations on which to take root. He was one of the first political agitators and public intellectuals in the contemporary sense of the term: not a solitary thinker or soldier but rather a political leader who sought popular support and participa tion. -

3.-Unifying-Italy.Pdf

WH07_TE_ch22_s03_na_s.fm Page 700 Tuesday, February 13, 2007 4:52wh07_se_ch22_s03_s.fm PM Page 700 Wednesday, December 6, 2006 3:15 PM Flag of Italy, 1833 Step-by-Step WITNESS HISTORY AUDIO SECTION Instruction 3 Stirrings of Nationalism After a failed revolution against Austrian rule in northern Objectives Italy, many rebels, fearing retribution, begged for funds to As you teach this section, keep students pay for safe passage to Spain. Giuseppe Mazzini (mat SEE focused on the following objectives to help nee), still a boy, described his reaction to the situation: them answer the Section Focus Question “ He (a rebel) held out a white handkerchief, merely say- and master core content. ing, ‘For the refugees of Italy.’ My mother . dropped 3 some money into the handkerchief. That day was the ■ List the key obstacles to Italian unity. first in which a confused idea presented itself to my mind ■ Understand what roles Count Camillo . an idea that we Italians could and therefore ought to Cavour and Giuseppe Garibaldi played struggle for the liberty of our country. .” in the struggle for Italy. —Giuseppe Mazzini, Life and Writings Focus Question How did influential leaders help to create ■ Describe the challenges that faced the Giuseppe Mazzini, a unified Italy? new nation of Italy. around 1865 Unifying Italy Prepare to Read Objectives Although the people of the Italian peninsula spoke the same lan- Build Background Knowledge L3 • List the key obstacles to Italian unity. guage, they had not experienced political unity since Roman Ask students to recall the issues facing • Understand what roles Count Camillo Cavour times. -

Il Risorgimento a Verona E Nel Veronese

Il Risorgimento a Verona e ne l Veronese provincia di verona FONDAZIONE F IORONI ASSESSORATO CULTURA, IDENTITÀ VENETA E BENI AMBIENTALI MUSEI E B IBLIOTECA P UBBLICA Il Risorgimento a Verona e ne l Veronese Coordinamento provinciale per il 150° anniversario dell’unità d’Italia A cura di Andrea Ferrarese provincia di verona FONDAZIONE F IORONI ASSESSORATO CULTURA, IDENTITÀ VENETA E BENI AMBIENTALI MUSEI E B IBLIOTECA P UBBLICA Coordinamento provinciale Comune di Verona Comune di Bardolino Comune di Comune di Legnago Comune di Pastrengo Castelnuovo del Garda Comune di Peschiera Comune di Rivoli Comune di Comune di Sona Comune di Comune di Villafranca Sommacampagna Valeggio sul Mincio FONDAZIONE F IORONI COMFOTER ISTITUTO STORICO MUSEI E B IBLIOTECA P UBBLICA ARCHITETTURA M ILITARE CON IL PATROCINIO DEL CONSIGLIO REGIONALE DEL VENETO alla primavera del 2010 l’Assessorato alla Cultura e DIdentità Veneta della Provincia di Verona ha promos- so, nell’ambito del 150° anniversario dell’unità d’Italia che corre quest’anno, un progetto di coordinamento tra le prin- cipali realtà territoriali veronesi interessate da momenti ed episodi salienti per la storia del Risorgimento a Verona e nel Veronese. Fin dai primi incontri e confronti nei mesi che hanno scan- dito l’avvicinarsi di ‘Italia 150’, è emersa con chiarezza la necessità di dare vita ad una “rete” di idee tra le ammini- strazioni comunali e gli enti coinvolti nella complessa pro- gettualità dell’evento, una rete in grado di promuovere e coordinare le sinergie culturali ed i programmi dei vari co- muni, per avvicinare il pubblico ai momenti salienti della storia risorgimentale. -

Mazzini's Filosofia Della Musica: an Early Nineteenth-Century Vision Of

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Arts and Architecture MAZZINI’S FILOSOFIA DELLA MUSICA: AN EARLY NINETEENTH-CENTURY VISION OF OPERATIC REFORM A Thesis in Musicology by Claire Thompson © 2012 Claire Thompson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts May 2012 ii The thesis of Claire Thompson was reviewed and approved* by the following: Charles Youmans Associate Professor of Musicology Thesis Adviser Marie Sumner Lott Assistant Professor of Musicology Sue Haug Director of the School of Music *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT Although he is better known for his political writings and for heading a series of failed revolutions in mid-nineteenth century Italy, Giuseppe Mazzini also delved into the realm of music aesthetics with his treatise Filosofia della Musica. Ignoring technical considerations, Mazzini concerned himself with the broader social implications of opera, calling for operatic reform to combat Italian opera’s materialism, its lack of unifying characteristics, and its privileging of melody over all other considerations. Mazzini frames his argument for the transformation of opera into a social art within the context of a larger Hegelian dialectic, which pits Italian music (which Mazzini associates with melody and the individual) against German music (which Mazzini associates with harmony and society). The resulting synthesis, according to Mazzini, would be a moral operatic drama, situating individuals within a greater society, and manifesting itself in a cosmopolitan or pan-European style of music. This thesis explores Mazzini’s treatise, including the context of its creation, the biases it demonstrates, the philosophical issues it raises about the nature and role of music, and the individual details of Mazzini’s vision of reform. -

Study Guide Fall 2016

Santa Reparata International School of Art Academic Year 2016/2017 Contemporary Italy professor dr. Lorenzo Pubblici Study Guide 1. The Italian Unification The notion of Risorgimento in Italian history What is the Risorgimento? • Traditional view: 1815-1871 • Modern view: 1789-1918 • Political Risorgimento and Literary Risorgimento Vittorio Alfieri (1749-1803) and other intellectuals Italy is a Country where the national culture was born before the Nation itself. Let’s see the steps towards the creation of the idea of Italy • Ancient Roman Empire: Augustus and the reform of the provinces • Free citizens were Roman citizen • 476: fall of the Roman Empire, the peninsular unity is not broken • VI Century: Byzantine-Gothic war • End of the VI Century: Lombard invasion, the Peninsula loses its geographical unity • The fusion of the two elements: germanic and latin The Franks • The invasion of the Franks (Charlemagne) breaks the Regnum Langobardorum • The Franks and the desire of autonomy of the Northern Italian cities • The attempts for an unitarian kingdom by Frederick 2nd, and birth of the Communes • The Roman Church remains the only identitarian power in Italy The intellectuals • The Regional States and the Signorie, late Middle Ages • The Humanism and the Rinascimento: Italy, heir of Rome. • Complaining of the actual situation (all the rulers in Italy are foreigners) Dante, Petrarca and Boccaccio and the Italian language • Cosimo dei Medici and Lorenzo as Pater Patriae • Machiavelli and Guicciardini: the central State and the Federal one The French Revolution and the Napoleonic period • The French Revolution, the Enlightenment and the results in Europe and in Italy • Napoleon invades Italy (1796). -

AP European History - Chapter 22 an Age of Nationalism and Realism, 1850-1871 Class Notes & Critical Thinking

AP European History - Chapter 22 An Age of Nationalism and Realism, 1850-1871 Class Notes & Critical Thinking Focus Question: What were the characteristics of Napoleon III’s government, and how did his foreign policy continue to the unification of Italy and Germany? Second French Republic Critical Thinking: • President Louis Napoleon: seen by voters as a symbol of stability and greatness • Dedicated to law and order, opposed to socialism and radicalism, and favored the conservative classes—the Church, army, property-owners, and business. • Universal suffrage The Second Empire (or Liberal Empire) • Emperor Napoleon III, 1851: took control of gov’t in coup d’etat (December 1851) and became emperor • 1851-1860: Napoleon III’s control was direct and authoritarian. • 1860-1870: Regime liberalized by a series of reforms. • Used nationalism to strengthen the state • Economic reforms resulted in a healthy economy • Infrastructure: canals, roads; Baron Haussmann redevelops Another Napoleon Emperor??? Why did Paris the French people want Napoleon III? • Movement towards free trade • Banking: Credit Mobilier funded industrial and infrastructure growth • Foreign policy struggles resulted in strong criticism of Napoleon III • Algeria, Crimean War, Italian unification struggles, colonial possessions in Africa, Mexico • Liberal reforms (done in part to divert attention from unsuccessful foreign policy) • Extended power of the Legislative Assembly • Returned control of secondary education to the government (instead of Catholic Church) • Permitted trade unions and right to strike • Eased censorship and granted amnesty to political prisoners • Franco-Prussian War and capture of Napoleon III results in collapse of 2nd Empire • Napoleon III’s rule provided a model for other political leaders in Europe. -

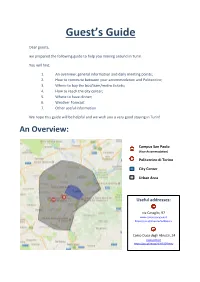

Guest's Guide

Guest’s Guide Dear guests, we prepared the following guide to help you moving around in Turin. You will find: 1. An overview: general information and daily meeting points; 2. How to commute between your accommodation and Politecnico; 3. Where to buy the bus/tram/metro tickets; 4. How to reach the city center; 5. Where to have dinner; 6. Weather Forecast 7. Other useful information We hope this guide will be helpful and we wish you a very good staying in Turin! An Overview: Campus San Paolo (Your Accommodation) Politecnico di Torino City Center Urban Area Useful addresses: via Caraglio, 97 www.campussanpaolo.it https://goo.gl/maps/aZVzf2pquHv Corso Duca degli Abruzzi, 24 www.polito.it https://goo.gl/maps/hLWP2ZYRmvy AIRPORT Transfer: From TORINO (Caselle) AIRPORT 1. The SADEM bus service connects Caselle Airport to the city center of Turin. The final stops of the bus are at Turin main railway stations: Porta Susa and Porta Nuova. We suggest you to stop at Porta Susa. Single ticket price: 6.50€ (+1,00€ if tickets are purchased on board). Journey time: 45/50 minutes. Departure location of the bus: Airport Arrival Area (ground floor). Tickets: The tickets can be purchased at the ticket office (Ricevitoria) and at ticket machines in the Arrival lounge; they can also be purchased on board (+1,00€ extra-charge). It is suggested to buy the tickets before getting on the bus. For the timetables you can visit the website: http://www.sadem.it/en/prodotti/collegamento- aeroporti/torino-caselle-international-airport.aspx From Porta Susa, to get to your accommodation at Campus SanPaolo (via Caraglio 97), you can take bus 55 towards Don Borio at Porta Susa bus stop (2668) and stop at Robilant bus stop (1513) – approx.