Kobus Ellipsiprymnus Ellipsiprymnus – Waterbuck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ntinini Controlled Hunting Area

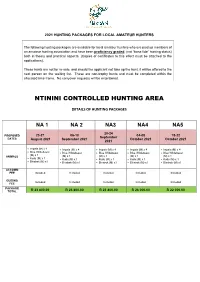

2021 HUNTING PACKAGES FOR LOCAL AMATEUR HUNTERS The following hunting packages are available for local amateur hunters who are paid up members of an amateur hunting association and have been proficiency graded, (not “bona fide” hunting status) both in theory and practical aspects. (Copies of certificates to this effect must be attached to the applications). These hunts are not for re-sale, and should the applicant not take up the hunt, it will be offered to the next person on the waiting list. These are non-trophy hunts and must be completed within the allocated time frame. No carryover requests will be entertained. NTININI CONTROLLED HUNTING AREA DETAILS OF HUNTING PACKAGES NA 1 NA 2 NA3 NA4 NA5 20-24 23-27 06-10 04-08 18-22 PROPOSED September DATES August 2021 September 2021 October 2021 October 2021 2021 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest (M) x 1 ANIMALS (M) x 1 (M) x 1 (M) x 1 (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 ACCOMM FEE Included Included Included Included Included GUIDING Included Included Included Included Included FEE PACKAGE TOTAL R 23 800.00 R 23 800.00 R 23 800.00 R 26 000.00 R 22 000.00 ITHALA CONTROLLED HUNTING AREA DETAILS OF HUNTING PACKAGES IGRA 1 IGRA 2 IGRA 3 IGRA 4 PROPOSED 11-16 02-07 16-21 06-11 DATES June 2021 July 2021 July 2021 August 2021 • Impala -

Demographic Observations of Mountain Nyala Tragelaphus Buxtoni in A

y & E sit nd er a v n i g d e Evangelista et al., J Biodivers Endanger Species 2015, 3:1 o i r e Journal of B d f S o p l e a c ISSN:n 2332-2543 1 .1000145 r i DOI: 0.4172/2332-2543 e u s o J Biodiversity & Endangered Species Research article Open Access Demographic Observations of Mountain Nyala Tragelaphus Buxtoni in a Controlled Hunting Area, Ethiopia Paul Evangelista1*, Nicholas Young1, David Swift1 and Asrat Wolde1 Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory Colorado State University B254 Fort Collins, Colorado *Corresponding author: Paul Evangelista, Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory Colorado State University B254 Fort Collins, Colorado, Tel: (970) 491-2302; E-mail: [email protected] Received date: December 4, 2014; Accepted date: January 30, 2015; Published date: February 6, 2015 Copyright: © 2015 Evangelista P. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract The highlands of Ethiopia are inhabited by the culturally and economically significant mountain nyala Tragelaphus buxtoni, an endemic spiral horned antelope. The natural range of this species has become highly fragmented with increasing anthropogenic pressures; driving land conversion in areas previously considered critical mountain nyala habitat. Therefore, baseline demographic data on this species throughout its existing range are needed. Previous studies on mountain nyala demographics have primarily focused on a confined portion of its known range where trophy hunting is not practiced. Our objectives were to estimate group size, proportion of females, age class proportions, and calf and juvenile productivity for a sub-population of mountain nyala where trophy hunting is permitted and compare our results to recent and historical observations. -

Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout Has in THIS ISSUE Dbeen Awarded the President’S Cup Letter from the President

DSC NEWSLETTER VOLUME 32,Camp ISSUE 5 TalkJUNE 2019 Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout has IN THIS ISSUE Dbeen awarded the President’s Cup Letter from the President .....................1 for her pending world record East African DSC Foundation .....................................2 Defassa Waterbuck. Awards Night Results ...........................4 DSC’s April Monthly Meeting brings Industry News ........................................8 members together to celebrate the annual Chapter News .........................................9 Trophy and Photo Award presentation. Capstick Award ....................................10 This year, there were over 150 entries for Dove Hunt ..............................................12 the Trophy Awards, spanning 22 countries Obituary ..................................................14 and almost 100 different species. Membership Drive ...............................14 As photos of all the entries played Kid Fish ....................................................16 during cocktail hour, the room was Wine Pairing Dinner ............................16 abuzz with stories of all the incredible Traveler’s Advisory ..............................17 adventures experienced – ibex in Spain, Hotel Block for Heritage ....................19 scenic helicopter rides over the Northwest Big Bore Shoot .....................................20 Territories, puku in Zambia. CIC International Conference ..........22 In determining the winners, the judges DSC Publications Update -

Population, Distribution and Conservation Status of Sitatunga (Tragelaphus Spekei) (Sclater) in Selected Wetlands in Uganda

POPULATION, DISTRIBUTION AND CONSERVATION STATUS OF SITATUNGA (TRAGELAPHUS SPEKEI) (SCLATER) IN SELECTED WETLANDS IN UGANDA Biological -Life history Biological -Ecologicl… Protection -Regulation of… 5 Biological -Dispersal Protection -Effectiveness… 4 Biological -Human tolerance Protection -proportion… 3 Status -National Distribtuion Incentive - habitat… 2 Status -National Abundance Incentive - species… 1 Status -National… Incentive - Effect of harvest 0 Status -National… Monitoring - confidence in… Status -National Major… Monitoring - methods used… Harvest Management -… Control -Confidence in… Harvest Management -… Control - Open access… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -Aim… Control of Harvest-in… Harvest Management -… Control of Harvest-in… Tragelaphus spekii (sitatunga) NonSubmitted Detrimental to Findings (NDF) Research and Monitoring Unit Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) Plot 7 Kira Road Kamwokya, P.O. Box 3530 Kampala Uganda Email/Web - [email protected]/ www.ugandawildlife.org Prepared By Dr. Edward Andama (PhD) Lead consultant Busitema University, P. O. Box 236, Tororo Uganda Telephone: 0772464279 or 0704281806 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Final Report i January 2019 Contents ACRONYMS, ABBREVIATIONS, AND GLOSSARY .......................................................... vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................... viii 1.1Background ........................................................................................................................... -

EST. S 1987 Wildlife Systems, Inc

EST. s 1987 Wildlife Systems, Inc. was founded in 1987 with a primary focus of providing a dual blend of hunting services for sportsmen seeking quality outdoor adventure, as well as providing landowners with wildlife management services, and this enterprise concept remains the same today. WSI has worked across most regions of Texas, several other states, and multiple foreign countries, and the company's ability to provide adaptive services is one of the unique features that have allowed WSI to successfully integrate into various settings, regardless of the region or resources of interest. WSI currently operates hunting programs on approximately 700,000 acres of private land, offering hunting services for a variety of game species, and hosts hunts each year for clients from over 30 states. Wildlife consulting is provided on numerous other properties which are not enrolled under a WSI hunting program. The growth and continued success of WSI is a direct funtion of a support staff who share in similar operational philosophies developed through company training protocols, striving to offer consistent quality service to our hunters and landowners. From office personnel to guides, cooks to field techs, part-time, fulltime, and seasonal, this group of 30-40 staffers represent the heartbeat of WSI. The quality of their work has been featured in many national and regional magazines, several major television networks, and have received various recognitions including being named the 2002 Dodge Outfitter of the Year, from a cast of over 400 different hunting operations in North America. Company founder and owner, Greg Simons, is a respected wildlife biologist who has been active in his professional peer field for many years, serving as an officer in Texas Chapter of The Wildlife Society and Texas Wildlife Associa tion. -

Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus Oryx) Meat Composition on Its Further Technological Processing

CZECH UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES PRAGUE Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences Department of Animal Science and Food Processing Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) Meat Composition on its further Technological Processing DISSERTATION THESIS Prague 2018 Author: Supervisor: Ing. et Ing. Petr Kolbábek prof. MVDr. Daniela Lukešová, CSc. Co-supervisors: Ing. Radim Kotrba, Ph.D. Ing. Ludmila Prokůpková, Ph.D. Declaration I hereby declare that I have done this thesis entitled “Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) Meat Composition on its further Technological Processing” independently, all texts in this thesis are original, and all the sources have been quoted and acknowledged by means of complete references and according to Citation rules of the FTA. In Prague 5th October 2018 ………..………………… Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to prof. MVDr. Daniela Lukešová CSc., Ing. Radim Kotrba, Ph.D. and Ing. Ludmila Prokůpková, Ph.D., and doc. Ing. Lenka Kouřimská, Ph.D., my research supervisors, for their patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and useful critiques of this research work. I am very gratefull to Ing. Petra Maxová and Ing. Eva Kůtová for their valuable help during the research. I am also gratefull to Mr. Petr Beluš, who works as a keeper of elands in Lány, Mrs. Blanka Dvořáková, technician in the laboratory of meat science. My deep acknowledgement belongs to Ing. Radek Stibor and Mr. Josef Hora, skilled butchers from the slaughterhouse in Prague – Uhříněves and to JUDr. Pavel Jirkovský, expert marksman, who shot the animals. I am very gratefull to the experts from the Natura Food Additives, joint-stock company and from the Alimpex-maso, Inc. -

Fitzhenry Yields 2016.Pdf

Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za iii GENERAL ABSTRACT Fallow deer (Dama dama), although not native to South Africa, are abundant in the country and could contribute to domestic food security and economic stability. Nonetheless, this wild ungulate remains overlooked as a protein source and no information exists on their production potential and meat quality in South Africa. The aim of this study was thus to determine the carcass characteristics, meat- and offal-yields, and the physical- and chemical-meat quality attributes of wild fallow deer harvested in South Africa. Gender was considered as a main effect when determining carcass characteristics and yields, while both gender and muscle were considered as main effects in the determination of physical and chemical meat quality attributes. Live weights, warm carcass weights and cold carcass weights were higher (p < 0.05) in male fallow deer (47.4 kg, 29.6 kg, 29.2 kg, respectively) compared with females (41.9 kg, 25.2 kg, 24.7 kg, respectively), as well as in pregnant females (47.5 kg, 28.7 kg, 28.2 kg, respectively) compared with non- pregnant females (32.5 kg, 19.7 kg, 19.3 kg, respectively). -

A National Park in Northern Rhodesia 15

A National Park in Northern Rhodesia 15 A NATIONAL PARK IN NORTHERN RHODESIA By a Proclamation dated 20th April, 1950, the Governor of Northern Rhodesia has established a National Park, to be known as the Kafue National Park. This new park covers some 8,650 square miles roughly in the central Kafue basin, between latitudes 14° and 16° 40' S. It contains a wide range of country from the comparatively drv sandy lands of the south to the big rivers, swamps, and heavy timber of the northern section. The magnificent Kafue River dominates the whole central portion, adding scenic beauty to the attraction of wild life. The park contains representatives of most species of the fauna of Northern Rhodesia. Primates are represented by the Rhodesian Baboon, the Vervet Monkey, and the Greater and Lesser Night-Apes. There are Elephant and Black Rhinoceros, Buffalo, Lion, Leopard, Cheetah, and numbers of the smaller carnivora. Antelope include Eland, Sable, Roan, Liehtenstein's Hartebeest, Blue Wildebeest, Kudu, Defassa Waterbuck, Bushbuck, Reedbuck, Puku, Impala, Oribi, Common, Blue, and Yellow-backed Duikers, Klipspringer, and Sharpe's Stein- buck. There are Red Lechwe and Sitatunga in the Busango Swamp in the north, Hippopotamus in numbers in the Kafue and its larger tributaries. Zebra are common, Warthog and Bushpig everywhere. Birds are abundant. The park is uninhabited apart from certain small settle- ments, on a limited section of the Kafue River, belonging to the indigenous Africans under their tribal chief Kayingu. These people must be accorded their traditional local hunting rights, but such will affect only a small fraction of the whole vast wild area. -

War and the White Rhinos

War and the White Rhinos Kai Curry-Lindahl Until 1963 the main population of the northern square-lipped (white) rhino was in the Garamba National Park, in the Congo (now Zaire) where they had increased to over 1200. That year armed rebels occupied the park, and when three years later they had been driven out, the rhinos had been drastically reduced: numbers were thought to be below 50. Dr. Curry-Iindahl describes what he found in 1966 and 1967. The northern race of the square-lipped rhinoceros Ceratotherium simum cottoni was once widely distributed in Africa north of the equator, but persecution has exterminated it over large areas. It is now known to occur only in south-western Sudan, north-eastern Congo (Kinshasa) and north-western Uganda. It is uncertain whether it still exists in northern Ubangui, in the Central African Republic. In the Sudan, where for more than ten years its range has been affected by war and serious disturbances, virtually nothing is known of its present status. In Uganda numbers dropped from about 350 in 1955 to 80 in 1962 and about 20-25 in 1969 (Cave 1963, Simon 1970); the twelve introduced into the Murchison Falls National Park in 1960, despite two being poached, increased to 18 in 1971. But the bulk of the population before 1963 was in the Garamba National Park in north-eastern Congo, in the Uele area. There, since 1938, it had been virtually undisturbed, and, thanks to the continuous research which characterised the Congo national parks before 1960, population figures are known for several periods (see the Table on page 264). -

Trophy Hunting

Original language: English CoP17 Inf. 60 (English only / Únicamente en inglés / Seulement en anglais) CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN ENDANGERED SPECIES OF WILD FAUNA AND FLORA ____________________ Seventeenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties Johannesburg (South Africa), 24 September – 5 October 2016 INFORMING DECISIONS ON TROPHY HUNTING This document has been submitted by the Secretariat on behalf of IUCN*, in relation to agenda item 39 on Hunting trophies. * The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CITES Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. CoP17 Inf. 60 – p. 1 BRIEFING PAPER September 2016 Informing decisions on trophy hunting A Briefing Paper regarding issues to be taken into account when considering restriction of imports of hunting trophies For more information: SUMMARY Dan Challender Trophy hunting is currently the subject of intense debate, with moves IUCN Global Species at various levels to end or restrict it, including through increased bans Programme or restrictions on carriage or import of trophies. This paper seeks to inform [email protected] these discussions. Rosie Cooney IUCN CEESP/SSC Trophy hunting is hunting of animals with specific desired characteristics Sustainable Use (such as large antlers), and overlaps with widely practiced hunting for meat. and Livelihoods Specialist Group It is clear that there have been, and continue to be, cases of poorly conducted [email protected] and poorly regulated hunting. -

Animals of Africa

Silver 49 Bronze 26 Gold 59 Copper 17 Animals of Africa _______________________________________________Diamond 80 PYGMY ANTELOPES Klipspringer Common oribi Haggard oribi Gold 59 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Copper 17 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Gold 61 Copper 17 Diamond 80 Diamond 80 Steenbok 1 234 5 _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ Cape grysbok BIG CATS LECHWE, KOB, PUKU Sharpe grysbok African lion 1 2 2 2 Common lechwe Livingstone suni African leopard***** Kafue Flats lechwe East African suni African cheetah***** _______________________________________________ Red lechwe Royal antelope SMALL CATS & AFRICAN CIVET Black lechwe Bates pygmy antelope Serval Nile lechwe 1 1 2 2 4 _______________________________________________ Caracal 2 White-eared kob DIK-DIKS African wild cat Uganda kob Salt dik-dik African golden cat CentralAfrican kob Harar dik-dik 1 2 2 African civet _______________________________________________ Western kob (Buffon) Guenther dik-dik HYENAS Puku Kirk dik-dik Spotted hyena 1 1 1 _______________________________________________ Damara dik-dik REEDBUCKS & RHEBOK Brown hyena Phillips dik-dik Common reedbuck _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________African striped hyena Eastern bohor reedbuck BUSH DUIKERS THICK-SKINNED GAME Abyssinian bohor reedbuck Southern bush duiker _______________________________________________African elephant 1 1 1 Sudan bohor reedbuck Angolan bush duiker (closed) 1 122 2 Black rhinoceros** *** Nigerian -

A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates

veterinary sciences Review A Scoping Review of Viral Diseases in African Ungulates Hendrik Swanepoel 1,2, Jan Crafford 1 and Melvyn Quan 1,* 1 Vectors and Vector-Borne Diseases Research Programme, Department of Veterinary Tropical Disease, Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria 0110, South Africa; [email protected] (H.S.); [email protected] (J.C.) 2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Institute of Tropical Medicine, 2000 Antwerp, Belgium * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +27-12-529-8142 Abstract: (1) Background: Viral diseases are important as they can cause significant clinical disease in both wild and domestic animals, as well as in humans. They also make up a large proportion of emerging infectious diseases. (2) Methods: A scoping review of peer-reviewed publications was performed and based on the guidelines set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping reviews. (3) Results: The final set of publications consisted of 145 publications. Thirty-two viruses were identified in the publications and 50 African ungulates were reported/diagnosed with viral infections. Eighteen countries had viruses diagnosed in wild ungulates reported in the literature. (4) Conclusions: A comprehensive review identified several areas where little information was available and recommendations were made. It is recommended that governments and research institutions offer more funding to investigate and report viral diseases of greater clinical and zoonotic significance. A further recommendation is for appropriate One Health approaches to be adopted for investigating, controlling, managing and preventing diseases. Diseases which may threaten the conservation of certain wildlife species also require focused attention.