Determinants of Vigilance in a Reintroduced Population of Père David’S Deer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

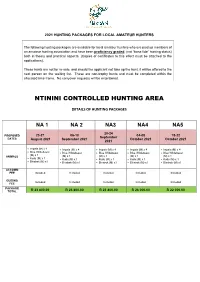

Ntinini Controlled Hunting Area

2021 HUNTING PACKAGES FOR LOCAL AMATEUR HUNTERS The following hunting packages are available for local amateur hunters who are paid up members of an amateur hunting association and have been proficiency graded, (not “bona fide” hunting status) both in theory and practical aspects. (Copies of certificates to this effect must be attached to the applications). These hunts are not for re-sale, and should the applicant not take up the hunt, it will be offered to the next person on the waiting list. These are non-trophy hunts and must be completed within the allocated time frame. No carryover requests will be entertained. NTININI CONTROLLED HUNTING AREA DETAILS OF HUNTING PACKAGES NA 1 NA 2 NA3 NA4 NA5 20-24 23-27 06-10 04-08 18-22 PROPOSED September DATES August 2021 September 2021 October 2021 October 2021 2021 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest (M) x 1 ANIMALS (M) x 1 (M) x 1 (M) x 1 (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 ACCOMM FEE Included Included Included Included Included GUIDING Included Included Included Included Included FEE PACKAGE TOTAL R 23 800.00 R 23 800.00 R 23 800.00 R 26 000.00 R 22 000.00 ITHALA CONTROLLED HUNTING AREA DETAILS OF HUNTING PACKAGES IGRA 1 IGRA 2 IGRA 3 IGRA 4 PROPOSED 11-16 02-07 16-21 06-11 DATES June 2021 July 2021 July 2021 August 2021 • Impala -

Cervid TB DPP Testing August 2017

Cervid TB DPP Testing August 2017 Elisabeth Patton, DVM, PhD, Diplomate ACVIM Veterinary Program Manager Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection Division of Animal Health Why Use the Serologic Test? Employ newer, accurate diagnostic test technology Minimizes capture and handling events for animal safety Expected to promote additional cervid TB testing • Requested by USAHA and cervid industry Comparable sensitivity and specificity to skin tests 2 Historical Timeline 3 Stat-Pak licensed for elk and red deer, 2009 White-tailed and fallow deer, 2010-11 2010 - USAHA resolution - USDA evaluate Stat-Pak as official TB test 2011 – Project to evaluate TB serologic tests in cervids (Cervid Serology Project); USAHA resolution to approve Oct 2012 – USDA licenses the Dual-Path Platform (DPP) secondary test for elk, red deer, white-tailed deer, and fallow deer Improved specificity compared to Stat-Pak Oct 2012 – USDA approves the Stat-Pak (primary) and DPP (secondary) as official bovine TB tests in elk, red deer, white- tailed deer, fallow deer and reindeer Recent Actions Stat-Pak is no longer in production 9 CFR 77.20 has been amended to approve the DPP as official TB program test. An interim rule was published on 9 January 2013 USDA APHIS created a Guidance Document (6701.2) to provide instructions for using the tests https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_ diseases/tuberculosis/downloads/vs_guidance_670 1.2_dpp_testing.pdf 4 Cervid Serology Project Objective 5 Evaluate TB detection tests for official bovine tuberculosis (TB) program use in captive and free- ranging cervids North American elk (Cervus canadensis) White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) Primary/screening test AND Secondary Test: Dual Path Platform (DPP) Rapid immunochromatographic lateral-flow serology test Detect antibodies to M. -

Bison and Elk in Yellowstone National Park - Linking Ecosystem, Animal Nutrition, and Population Processes

Bison and Elk in Yellowstone National Park - Linking Ecosystem, Animal Nutrition, and Population Processes Part 3 - Final Report to U.S. Geological Survey Biological Resources Division Bozeman, MT Project: Spatial-Dynamic Modeling of Bison Carrying Capacity in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: A Synthesis of Bison Movements, Population Dynamics, and Interactions with Vegetation Michael B. Coughenour Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado December 2005 INTRODUCTION Over the last three decades bison in Yellowstone National Park have increased in numbers and expanded their ranges inside the park up to and beyond the park boundaries (Meagher 1989a,b, Taper et al. 2000, Meagher et al. 2003). Potentially, they have reached, if not exceeded the capacity of the park to support them. The bison are infected with brucellosis, and it is feared that the disease will be readily transmitted to domestic cattle, with widespread economic repercussions. Brucellosis is an extremely damaging disease for livestock, causing abortions and impaired calf growth. After a long campaign beginning in 1934 and costing over $1.3 billion (Thorne et al. 1991), brucellosis has been virtually eliminated from cattle and bison everywhere in the conterminous United States except in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Infection of any livestock in Montana, Idaho, or Wyoming would result in that state losing its brucellosis-free status, leading to considerable economic hardships resulting from intensified surveillance, testing, and control (Thorne et al. 1991). Management alternatives that have been considered include hazing animals back into the park, the live capture and holding of animals that leave the park, and culling or removal from within the park. -

Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout Has in THIS ISSUE Dbeen Awarded the President’S Cup Letter from the President

DSC NEWSLETTER VOLUME 32,Camp ISSUE 5 TalkJUNE 2019 Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout has IN THIS ISSUE Dbeen awarded the President’s Cup Letter from the President .....................1 for her pending world record East African DSC Foundation .....................................2 Defassa Waterbuck. Awards Night Results ...........................4 DSC’s April Monthly Meeting brings Industry News ........................................8 members together to celebrate the annual Chapter News .........................................9 Trophy and Photo Award presentation. Capstick Award ....................................10 This year, there were over 150 entries for Dove Hunt ..............................................12 the Trophy Awards, spanning 22 countries Obituary ..................................................14 and almost 100 different species. Membership Drive ...............................14 As photos of all the entries played Kid Fish ....................................................16 during cocktail hour, the room was Wine Pairing Dinner ............................16 abuzz with stories of all the incredible Traveler’s Advisory ..............................17 adventures experienced – ibex in Spain, Hotel Block for Heritage ....................19 scenic helicopter rides over the Northwest Big Bore Shoot .....................................20 Territories, puku in Zambia. CIC International Conference ..........22 In determining the winners, the judges DSC Publications Update -

Differential Habitat Selection by Moose and Elk in the Besa-Prophet Area of Northern British Columbia

ALCES VOL. 44, 2008 GILLINGHAM AND PARKER – HABITAT SELECTION BY MOOSE AND ELK DIFFERENTIAL HABITAT SELECTION BY MOOSE AND ELK IN THE BESA-PROPHET AREA OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA Michael P. Gillingham and Katherine L. Parker Natural Resources and Environmental Studies Institute, University of Northern British Columbia, 3333 University Way, Prince George, British Columbia, Canada V2N 4Z9, email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Elk (Cervus elaphus) populations are increasing in the Besa-Prophet area of northern British Columbia, coinciding with the use of prescribed burns to increase quality of habitat for ungu- lates. Moose (Alces alces) and elk are now the 2 large-biomass species in this multi-ungulate, multi- predator system. Using global positioning satellite (GPS) collars on 14 female moose and 13 female elk, remote-sensing imagery of vegetation, and assessments of predation risk for wolves (Canis lupus) and grizzly bears (Ursus arctos), we examined habitat use and selection. Seasonal ranges were typi- cally smallest for moose during calving and for elk during winter and late winter. Both species used largest ranges in summer. Moose and elk moved to lower elevations from winter to late winter, but subsequent calving strategies differed. During calving, moose moved to lowest elevations of the year, whereas elk moved back to higher elevations. Moose generally selected for mid-elevations and against steep slopes; for Stunted spruce habitat in late winter; for Pine-spruce in summer; and for Subalpine during fall and winter. Most recorded moose locations were in Pine-spruce during late winter, calv- ing, and summer, and in Subalpine during fall and winter. -

Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist

STATE OF NEVADA Steve Sisolak, Governor DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE Tony Wasley, Director GAME DIVISION Brian F. Wakeling, Chief Mike Cox, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goat Staff Specialist Pat Jackson, Predator Management Staff Specialist Cody McKee, Elk Staff Biologist Cody Schroeder, Mule Deer and Antelope Staff Specialist Peregrine Wolff, Wildlife Health Specialist Western Region Southern Region Eastern Region Regional Supervisors Mike Scott Steve Kimble Tom Donham Big Game Biologists Chris Hampson Joe Bennett Travis Allen Carl Lackey Pat Cummings Clint Garrett Kyle Neill Cooper Munson Sarah Hale Ed Partee Kari Huebner Jason Salisbury Matt Jeffress Kody Menghini Tyler Nall Scott Roberts This publication will be made available in an alternative format upon request. Nevada Department of Wildlife receives funding through the Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration. Federal Laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, sex, or disability. If you believe you’ve been discriminated against in any NDOW program, activity, or facility, please write to the following: Diversity Program Manager or Director U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Nevada Department of Wildlife 4401 North Fairfax Drive, Mailstop: 7072-43 6980 Sierra Center Parkway, Suite 120 Arlington, VA 22203 Reno, Nevada 8911-2237 Individuals with hearing impairments may contact the Department via telecommunications device at our Headquarters at 775-688-1500 via a text telephone (TTY) telecommunications device by first calling the State of Nevada Relay Operator at 1-800-326-6868. NEVADA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE 2018-2019 BIG GAME STATUS This program is supported by Federal financial assistance titled “Statewide Game Management” submitted to the U.S. -

Educator's Guide

Educator’s Guide the jill and lewis bernard family Hall of north american mammals inside: • Suggestions to Help You come prepared • essential questions for Student Inquiry • Strategies for teaching in the exhibition • map of the Exhibition • online resources for the Classroom • Correlations to science framework • glossary amnh.org/namammals Essential QUESTIONS Who are — and who were — the North as tundra, winters are cold, long, and dark, the growing season American Mammals? is extremely short, and precipitation is low. In contrast, the abundant precipitation and year-round warmth of tropical All mammals on Earth share a common ancestor and and subtropical forests provide optimal growing conditions represent many millions of years of evolution. Most of those that support the greatest diversity of species worldwide. in this hall arose as distinct species in the relatively recent Florida and Mexico contain some subtropical forest. In the past. Their ancestors reached North America at different boreal forest that covers a huge expanse of the continent’s times. Some entered from the north along the Bering land northern latitudes, winters are dry and severe, summers moist bridge, which was intermittently exposed by low sea levels and short, and temperatures between the two range widely. during the Pleistocene (2,588,000 to 11,700 years ago). Desert and scrublands are dry and generally warm through- These migrants included relatives of New World cats (e.g. out the year, with temperatures that may exceed 100°F and dip sabertooth, jaguar), certain rodents, musk ox, at least two by 30 degrees at night. kinds of elephants (e.g. -

Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus Oryx) Meat Composition on Its Further Technological Processing

CZECH UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES PRAGUE Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences Department of Animal Science and Food Processing Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) Meat Composition on its further Technological Processing DISSERTATION THESIS Prague 2018 Author: Supervisor: Ing. et Ing. Petr Kolbábek prof. MVDr. Daniela Lukešová, CSc. Co-supervisors: Ing. Radim Kotrba, Ph.D. Ing. Ludmila Prokůpková, Ph.D. Declaration I hereby declare that I have done this thesis entitled “Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) Meat Composition on its further Technological Processing” independently, all texts in this thesis are original, and all the sources have been quoted and acknowledged by means of complete references and according to Citation rules of the FTA. In Prague 5th October 2018 ………..………………… Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to prof. MVDr. Daniela Lukešová CSc., Ing. Radim Kotrba, Ph.D. and Ing. Ludmila Prokůpková, Ph.D., and doc. Ing. Lenka Kouřimská, Ph.D., my research supervisors, for their patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and useful critiques of this research work. I am very gratefull to Ing. Petra Maxová and Ing. Eva Kůtová for their valuable help during the research. I am also gratefull to Mr. Petr Beluš, who works as a keeper of elands in Lány, Mrs. Blanka Dvořáková, technician in the laboratory of meat science. My deep acknowledgement belongs to Ing. Radek Stibor and Mr. Josef Hora, skilled butchers from the slaughterhouse in Prague – Uhříněves and to JUDr. Pavel Jirkovský, expert marksman, who shot the animals. I am very gratefull to the experts from the Natura Food Additives, joint-stock company and from the Alimpex-maso, Inc. -

Pbmr-400 Benchmark Solution of Exercise 1 and 2 Using the Moose Based Applications: Mammoth, Pronghorn

EPJ Web of Conferences 247, 06020 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1051/epjconf/202124706020 PHYSOR2020 PBMR-400 BENCHMARK SOLUTION OF EXERCISE 1 AND 2 USING THE MOOSE BASED APPLICATIONS: MAMMOTH, PRONGHORN Paolo Balestra1, Sebastian Schunert1, Robert W Carlsen1, April J Novak2 Mark D DeHart1, Richard C Martineau1 1Idaho National Laboratory 955 MK Simpson Blvd, Idaho Falls, ID 83401, USA 2University of California, Berkeley 2000 Carleton Street, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT High temperature gas cooled reactors (HTGR) are a candidate for timely Gen-IV reac- tor technology deployment because of high technology readiness and walk-away safety. Among HTGRs, pebble bed reactors (PBRs) have attractive features such as low excess reactivity and online refueling. Pebble bed reactors pose unique challenges to analysts and reactor designers such as continuous burnup distribution depending on pebble mo- tion and recirculation, radiative heat transfer across a variety of gas-filled gaps, and long design basis transients such as pressurized and depressurized loss of forced circulation. Modeling and simulation is essential for both the PBR’s safety case and design process. In order to verify and validate the new generation codes the Nuclear Energy Agency (NEA) Data bank provide a set of benchmarks data together with solutions calculated by the participants using the state of the art codes of that time. An important milestone to test the new PBR simulation codes is the OECD NEA PBMR-400 benchmark which includes thermal hydraulic and neutron kinetic standalone exercises as well as coupled exercises and transients scenarios. -

Antelope, Deer, Bighorn Sheep and Mountain Goats: a Guide to the Carpals

J. Ethnobiol. 10(2):169-181 Winter 1990 ANTELOPE, DEER, BIGHORN SHEEP AND MOUNTAIN GOATS: A GUIDE TO THE CARPALS PAMELA J. FORD Mount San Antonio College 1100 North Grand Avenue Walnut, CA 91739 ABSTRACT.-Remains of antelope, deer, mountain goat, and bighorn sheep appear in archaeological sites in the North American west. Carpal bones of these animals are generally recovered in excellent condition but are rarely identified beyond the classification 1/small-sized artiodactyl." This guide, based on the analysis of over thirty modem specimens, is intended as an aid in the identifi cation of these remains for archaeological and biogeographical studies. RESUMEN.-Se han encontrado restos de antilopes, ciervos, cabras de las montanas rocosas, y de carneros cimarrones en sitios arqueol6gicos del oeste de Norte America. Huesos carpianos de estos animales se recuperan, por 10 general, en excelentes condiciones pero raramente son identificados mas alIa de la clasifi cacion "artiodactilos pequeno." Esta glia, basada en un anaIisis de mas de treinta especlmenes modemos, tiene el proposito de servir como ayuda en la identifica cion de estos restos para estudios arqueologicos y biogeogrMicos. RESUME.-On peut trouver des ossements d'antilopes, de cerfs, de chevres de montagne et de mouflons des Rocheuses, dans des sites archeologiques de la . region ouest de I'Amerique du Nord. Les os carpeins de ces animaux, generale ment en excellente condition, sont rarement identifies au dela du classement d' ,I artiodactyles de petite taille." Le but de ce guide base sur 30 specimens recents est d'aider aidentifier ces ossements pour des etudes archeologiques et biogeo graphiques. -

Serologic Surveys for Natural Foci of Contagious Ecthyma Infection

FI.NAL REP.ORT (R.ESEARCH) State: Alaska Cooperators: Randall L. Zarnke and Kenneth A. Neiland Project No.: W-21-1 Project Title: Big Game Investigations Job No.: l8.1R Job Title: Serologic Surveys for Natural Foci of contag1ous Ecthyma Infection Period Covered: July 1, 1979 to J~~? ~0, 1~80 SUMMARY Contagious ecthyma (C. E. ) antibody prevalence in domestic sheep and goats in Interior Alaska du~ing 1978 was quite low (7-10%). This suggested a low level of transmission of the virus among these species during this time period. C. E. antibody prevalence in Dall sheep increased .from 30 percent in 1971 to 100 percent in 1978. This suggested an increased level of transmission to, and/or among, these animals during this period. Following a C.E. epizootic in a band of captive Dall sheep in 1977, antibody prevalence was 80 percent in this group of sheep. Less than l year later, prevalence had dropped to 10 percent in the ·same band. Thus it appeared that antibody produced in response to this . strain of C.E. is short-lived. Antibody was also detected in 10 of 22 free ranging muskoxen taken by sport hunters on Nunivak Island in 1978. Detectable antibody levels were not found in any of 19 muskoxen captured on the island in 1979. No antibody was found in a small number of captive muskoxen from Unalakleet. Several of the captive muskoxen were ·known to have been infected with C.E. within 1 to 2 years prior to the time of sampling. This further substantiates the belief that anti body produced in response to infection by the Alaskan strain of C.E. -

Bighorn Sheep, Moose, and Mountain Goats

Bighorn Sheep, Moose, and Mountain Goats Brock Hoenes Ungulate Section Manager, Wildlife Program WACs: 220-412-070 Big game and wild turkey auction, raffle, and special incentive permits. 220-412-080 Special hunting season permits. 220-415-070 Moose seasons, permit quotas, and areas. 220-415-120 2021 Bighorn sheep seasons and permit quotas. 220-415-130 2021 Mountain goat seasons and permit quotas. 1. Special Hunting Season Permits 2. Moose – Status, recommendations, public comment 3. Mountain Goat – Status, recommendations, public comment 4. Bighorn Sheep – Status, recommendations, public comment 5. Questions Content Department of Fish and Wildlife SPECIAL HUNTING SEASON PERMITS White‐Tailed DeerWAC 220-412-080 • Allow successful applicants for all big game special permits to return their permit to the Department for any Agree 77% reason two weeks prior to the Neutral 9% opening day of the season and to have their points restored Disagree 14% 1,553 Respondents • Remove the “once‐in‐a‐lifetime” Public Comment restriction for Mountain Goat Conflict • 223 comments, 1 email/letter Reduction special permit category • General (90 agree, 26 disagree) • Reissue permit (67) • >2 weeks (21) • No change (12) Department of Fish and Wildlife MOOSE • Primarily occur in White‐Tailed DeerNE and north-central Washington • Most recent estimate in 2016 indicated ~5,000 moose in NE • Annual surveys to estimate age and sex ratios (snow dependent) • Recent studies (2014-2018) in GMUs 117 and 124 indicated populations were declining • Poor body condition (adult female) • Poor calf survival • Wolf predation • Tick infestations • Substantial reduction in antlerless permits in 2018 Department of Fish and Wildlife MOOSE RECOMMENDATIONS 1.