Differential Habitat Selection by Moose and Elk in the Besa-Prophet Area of Northern British Columbia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cervid TB DPP Testing August 2017

Cervid TB DPP Testing August 2017 Elisabeth Patton, DVM, PhD, Diplomate ACVIM Veterinary Program Manager Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection Division of Animal Health Why Use the Serologic Test? Employ newer, accurate diagnostic test technology Minimizes capture and handling events for animal safety Expected to promote additional cervid TB testing • Requested by USAHA and cervid industry Comparable sensitivity and specificity to skin tests 2 Historical Timeline 3 Stat-Pak licensed for elk and red deer, 2009 White-tailed and fallow deer, 2010-11 2010 - USAHA resolution - USDA evaluate Stat-Pak as official TB test 2011 – Project to evaluate TB serologic tests in cervids (Cervid Serology Project); USAHA resolution to approve Oct 2012 – USDA licenses the Dual-Path Platform (DPP) secondary test for elk, red deer, white-tailed deer, and fallow deer Improved specificity compared to Stat-Pak Oct 2012 – USDA approves the Stat-Pak (primary) and DPP (secondary) as official bovine TB tests in elk, red deer, white- tailed deer, fallow deer and reindeer Recent Actions Stat-Pak is no longer in production 9 CFR 77.20 has been amended to approve the DPP as official TB program test. An interim rule was published on 9 January 2013 USDA APHIS created a Guidance Document (6701.2) to provide instructions for using the tests https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_ diseases/tuberculosis/downloads/vs_guidance_670 1.2_dpp_testing.pdf 4 Cervid Serology Project Objective 5 Evaluate TB detection tests for official bovine tuberculosis (TB) program use in captive and free- ranging cervids North American elk (Cervus canadensis) White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) Primary/screening test AND Secondary Test: Dual Path Platform (DPP) Rapid immunochromatographic lateral-flow serology test Detect antibodies to M. -

Bison and Elk in Yellowstone National Park - Linking Ecosystem, Animal Nutrition, and Population Processes

Bison and Elk in Yellowstone National Park - Linking Ecosystem, Animal Nutrition, and Population Processes Part 3 - Final Report to U.S. Geological Survey Biological Resources Division Bozeman, MT Project: Spatial-Dynamic Modeling of Bison Carrying Capacity in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: A Synthesis of Bison Movements, Population Dynamics, and Interactions with Vegetation Michael B. Coughenour Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado December 2005 INTRODUCTION Over the last three decades bison in Yellowstone National Park have increased in numbers and expanded their ranges inside the park up to and beyond the park boundaries (Meagher 1989a,b, Taper et al. 2000, Meagher et al. 2003). Potentially, they have reached, if not exceeded the capacity of the park to support them. The bison are infected with brucellosis, and it is feared that the disease will be readily transmitted to domestic cattle, with widespread economic repercussions. Brucellosis is an extremely damaging disease for livestock, causing abortions and impaired calf growth. After a long campaign beginning in 1934 and costing over $1.3 billion (Thorne et al. 1991), brucellosis has been virtually eliminated from cattle and bison everywhere in the conterminous United States except in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Infection of any livestock in Montana, Idaho, or Wyoming would result in that state losing its brucellosis-free status, leading to considerable economic hardships resulting from intensified surveillance, testing, and control (Thorne et al. 1991). Management alternatives that have been considered include hazing animals back into the park, the live capture and holding of animals that leave the park, and culling or removal from within the park. -

BISON Workshop Slides

Bison Workshop Implicit, parallel, fully-coupled nuclear fuel performance analysis Computational Mechanics and Materials Department Idaho National Laboratory Table of ContentsI Bison Overview . 4 Getting Started with Bison . 19 Git...........................................................20 Building Bison . 28 Cloning to a New Machine . 30 Contributing to Bison. .31 External Users. .35 Thermomechanics Basics . 37 Heat Conduction . 40 Solid Mechanics . 55 Contact . 66 Fuels Specific Models . 80 Example Problem . 89 Mesh Generation. .132 Running Bison . 147 Postprocessing. .159 Best Practices and Solver Options (Advanced Topic) . 224 Adding a New Material Model to Bison . 239 2 / 277 Table of ContentsII Adding a Regression Test to bison/test . 261 Additional Information . 273 References . 276 3 / 277 Bison Overview Bison Team Members • Rich Williamson • Al Casagranda – [email protected] – [email protected] • Steve Novascone • Stephanie Pitts – [email protected] – [email protected] • Jason Hales • Adam Zabriskie – [email protected] – [email protected] • Ben Spencer • Wenfeng Liu – [email protected] – [email protected] • Giovanni Pastore • Ahn Mai – [email protected] – [email protected] • Danielle Petersen • Jack Galloway – [email protected] – [email protected] • Russell Gardner • Christopher Matthews – [email protected] – [email protected] • Kyle Gamble – [email protected] 5 / 277 Fuel Behavior: Introduction At beginning of life, a fuel element is quite simple... Michel et al., Eng. Frac. Mech., 75, 3581 (2008) Olander, p. 323 (1978) =) Fuel Fracture Fission Gas but irradiation brings about substantial complexity... Olander, p. 584 (1978) Bentejac et al., PCI Seminar (2004) Multidimensional Contact and Stress Corrosion Deformation Cracking Cladding Nakajima et al., Nuc. -

Horned Animals

Horned Animals In This Issue In this issue of Wild Wonders you will discover the differences between horns and antlers, learn about the different animals in Alaska who have horns, compare and contrast their adaptations, and discover how humans use horns to make useful and decorative items. Horns and antlers are available from local ADF&G offices or the ARLIS library for teachers to borrow. Learn more online at: alaska.gov/go/HVNC Contents Horns or Antlers! What’s the Difference? 2 Traditional Uses of Horns 3 Bison and Muskoxen 4-5 Dall’s Sheep and Mountain Goats 6-7 Test Your Knowledge 8 Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, 2018 Issue 8 1 Sometimes people use the terms horns and antlers in the wrong manner. They may say “moose horns” when they mean moose antlers! “What’s the difference?” they may ask. Let’s take a closer look and find out how antlers and horns are different from each other. After you read the information below, try to match the animals with the correct description. Horns Antlers • Made out of bone and covered with a • Made out of bone. keratin layer (the same material as our • Grow and fall off every year. fingernails and hair). • Are grown only by male members of the • Are permanent - they do not fall off every Cervid family (hoofed animals such as year like antlers do. deer), except for female caribou who also • Both male and female members in the grow antlers! Bovid family (cloven-hoofed animals such • Usually branched. -

The American Bison in Alaska

THE AMERICAN BISON IN ALASKA THE AMERICAN BISON IN ALASKA Game Division March 1980 ~~!"·e· ·nw ,-·-· '(' INDEX Page No. 1 cr~:;'~;:,\L I ··~''l·'O'K'\L\TTO:J. Tk·:;criptiun . , • 1 Lif<.: History .• . 1 Novcme:nts and :food Habits . 2 HISTO:~Y or BISO:J IN ALASKA .• • 2 Prehistoric to A.D. 1500. • 3 A.D. 1500 to Present. • 3 Transplants • • . .. 3 BISON ,\.'m AGRICl:LTURE IN ALASK.-'1.. • 4 Conflicts at Delta... , • • 4 The Keys ta Successful Operation of the Delta Junction Bi:;on Runge • . 5 DELT;\ JU!\CTION BISON RANGE .. • • . 6 Delta Land Management Plan. • . 6 Present Status...•• 7 Bison Range Development Plans • . 7 DO~~STICATIO~ Or BISON . 8 BISU:j AND OUTrlOOR RECREATIOi'l 9 Hunting . • • •••• 9 Plw Lot;r::Iphy and Viewing 10 AHF \S IN ALA:;KA SUITABLE FOR BISON TR.fu'\SPLANTS 10 11 13 The ,\ncri c1n bL~on (Bison bison) is one of the largest and most distinctive an1n..·'ells · found in North America. A full-gro\-.'11 bull stands 5 to 6 feet at the shnul.1 r, is 9 to 9 1/2 feet long and can weigh more than 2,000 pounds. Full-grown cows are smaller, but have been known to weigh over 1 300 pounds. A bison's head and forequarters are so massive that they s~c~ out of proportion to their smaller hind parts. Bison have a hump formed by a gradual lengthening of the back, or dorsal vertebrae, begin ning just ahead of the hips and reaching its maximum height above the front shoulder. -

Moose Alces Americanus

Wyoming Species Account Moose Alces americanus REGULATORY STATUS USFWS: No special status USFS R2: No special status USFS R4: No special status Wyoming BLM: No special status State of Wyoming: Big Game Animal (see regulations) CONSERVATION RANKS USFWS: No special status WGFD: NSS4 (Bc), Tier II WYNDD: G5, S4 Wyoming Contribution: LOW IUCN: Least Concern STATUS AND RANK COMMENTS Moose (Alces americanus) is classified as a big game animal in Wyoming by W.S. § 23-1-101 1. Harvest is regulated by Chapter 8 of Wyoming Game and Fish Commission Regulations 2. NATURAL HISTORY Taxonomy: Bradley et al. (2014), following Boyeskorov (1999), has recognized North American/Siberian Moose as A. americanus, separate from European Moose (A. alces) based on chromosome differences 3, 4. Bowyer et al. (2000) cautions against using chromosome numbers to designate speciation in large mammals 5. Molecular 6 and morphological 7 evidence supports a single species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature recognizes two separate species but acknowledges this is not a settled matter 8. George Shiras III first described this unique mountain race of Moose during his explorations in Yellowstone National Park, from 1908 to 1910 9. In honor of Shiras, Dr. Edward W. Nelson named the Yellowstone or Wyoming Moose A. alces shirasi 10. That original subspecies designation is now recognized as A. americanus shirasi, Shiras Moose, which is the only recognized subspecies of Moose in Wyoming and surrounding states. Three other recognized subspecies occur in distant portions of North America, with an additional 4 subspecies in Eurasia 6, 11. Description: Moose is the largest big game animal in Wyoming and the largest member of the cervid family. -

Guided Elk Hunt in Utah

Guided Elk Hunt In Utah MarshalIs Cass alwaysis enforcedly indubitable appositely and dowable after exergual when incurvedKeenan flumpsome hishorseradishes milliards environmentally. very tetanically and amiably? Ralph stamp sprucely? Check snap their mule deer hunt in Wyoming, that is manifest a moving one. Utah state within, these some be added to all hunts. Accommodations and your home cooked meals are included the cover Business Bureau as her private. Hunting in Utah With an immense amount of ancient land, Utah has a great variety a big nor to hunt, including mule deer, crest, mountain by, moose, bighorn sheep, pronghorn, mountain lion, bison and wild turkeys. Eli whispered to me to get ready and even threw the rifle up stale the outlet opening round the trees. All wanted our hurt is trophy bull elk paradise. Starts going big the mountain or nearly dies because he appear so over heated. Spring hunts available than May, stumble Fall hunts in August and September. Search which not successful for the requested address. The LC Ranch in northeastern Utah is the Elk Hunters paradise. Archery Trophy Mule Deer Hunts on general Property with Guaranteed Landowner Deer Vouchers. Some guides made more money delicate the wranglers but chess a lot. We offer hunts for Elk limited entry bull spike and cow Deer Rocky Mountain. Thanks for the info, Serge. Rich: bastard you ever fresh to hunt with a Limited Entry tag, the odds dictate that sue will have to search building bonus points in Utah. Close; Let us help people apply all New Mexico tags. This hunt is ancestor to something first hunt, with hunters staying in a motel in Coalville and meeting their guides each sleeve for the hunt. -

Moose March 2014

Volume 27/Issue 7 Moose March 2014 MOOSE © Hagerty Ryan, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service © Steve Kraemer MOOSE There are large shadows in Idaho’s Only males grow antlers. Both the keep the calf well hidden for the forests. They are huge but hide males and females have a flap of first few weeks. A moose is very very well. These shadows love to skin and hair hanging from their protective of her calf. She will be around wet meadows, streams, throats. It’s called a bell or dewlap. charge anything that gets too close lakes and ponds. Sometimes the The bell helps moose “talk” to each by rushing forward and striking only way you may know they are other. The bell has scent glands with both front feet. there is by the rustling of leaves on it. The smells on a male’s bell and shaking of twigs. This shadow lets a female know that he likes A calf weighs between 20 to 35 is the moose (Alces americanus). her. A full grown male, called a pounds when born, but it grows bull, may stand six feet high at the quickly on its mother’s rich milk. The name moose comes from the shoulder and weigh 1,000 to 1,600 By the time the calf is one week Algonquian Indian word “mons” pounds. The female, called a cow, old, it can run faster than a man. which means twig eater. What is smaller; she may weigh between Plants become part of a calf’s diet an appropriate name; moose are 800 and 1,300 pounds. -

American Elk (Cervus Elaphus)

American Elk (Cervus elaphus) November 1999 Fish and Wildlife Habitat Management Leaflet Number 11 General Information Before European settlement, an estimated ten million elk roamed the North American continent. The American elk (Cervus elaphus), or wapiti, a Native American word meaning “white rump,” once had the largest range of any deer species in North America. For centuries, the elk has been a picturesque icon of the American west and has pro- vided recreational opportunities for hunters, photographers, artists, and other wildlife enthusiasts. Unregulated hunting, grazing compe- tition from domestic livestock, and habitat destruction from unre- strained timber harvesting, urbanization, and westward expansion throughout the nineteenth century reduced American elk populations to less than 100,000 individuals continent-wide by the early 1900s. Fortunately, the elk’s ability to use a variety of habitats, its opportun- istic feeding habits, and positive response to management efforts has Bull elk enabled the species to survive natural and human-induced pressures over time. These factors, coupled with concentrated wildlife management efforts, have returned the American elk to stable, and in some areas increasing, populations in the United States and Canada. This pamphlet is designed to serve as an introduction to elk habitat requirements and to assist private landowners and managers in developing elk management plans. Success of any individual species management plan depends on targeting the specific needs of the desired species, analyzing the desig- nated habitat area as a whole to ensure that all required habitat elements are present, and determining what management techniques will best improve the land as elk habitat. Range Four subspecies of American elk live in North America today. -

Multiscale Investigation of Fission Gas for the Development of Fuel

Multiscale Investigation of Fission Gas for the Development of Fuel Performance Materials Models MOOSE Team: Derek Gaston1, Cody Permann1, David Andrs1, John Peterson1 MARMOT Team: Bulent Biner1, Michael Tonks1, Paul Millett1,Yongfeng Zhang1, David Andersson2, Chris Stanek2 BISON Team: Richard Williamson1, Jason Hales1, Steve Novascone1, Ben Spencer1, Giovanni Pastore1 1Idaho National Laboratory 2 Los Alamos National Laboratory www.inl.gov www.inl.gov Presentation Summary: • The US Department of Energy Nuclear Energy Advanced Modeling and Simulation Program (NEAMS) seeks to rapidly create and deploy “science-based” verified and validated modeling and simulation capabilities essential for the design, implementation, and operation of future nuclear energy systems. • In this talk, I will summarize NEAMS-funded efforts to develop advanced materials models for fuel performance using multiscale modeling and simulation. • Outline: 1. MOOSE-BISON-MARMOT 2. MOOSE summary 3. BISON summary 4. MARMOT summary 5. Example of multiscale model development LWR Fuel Behavior Modeling – U.S. State of the Art • Fuel performance codes are used today for determination of operational margins by calculating property evolution. • However, current US industry standard codes (e.g. FRAPCON and FALCON) have limitations in three main areas: Numerical Capabilities Geometry representation Materials models • Serial • 1.5 or 2-D • Empirical • Inefficient Solvers • Smeared Pellets • Models only valid in • Loosely Coupled • Restricted to LWR Fuel limited conditions • High -

A Field Guide to Common Wildlife Diseases and Parasites in the Northwest Territories

A Field Guide to Common Wildlife Diseases and Parasites in the Northwest Territories 6TH EDITION (MARCH 2017) Introduction Although most wild animals in the NWT are healthy, diseases and parasites can occur in any wildlife population. Some of these diseases can infect people or domestic animals. It is important to regularly monitor and assess diseases in wildlife populations so we can take steps to reduce their impact on healthy animals and people. • recognize sickness in an animal before they shoot; •The identify information a disease in this or field parasite guide in should an animal help theyhunters have to: killed; • know how to protect themselves from infection; and • help wildlife agencies monitor wildlife disease and parasites. The diseases in this booklet are grouped according to where they are most often seen in the body of the Generalanimal: skin, precautions: head, liver, lungs, muscle, and general. Hunters should look for signs of sickness in animals • poor condition (weak, sluggish, thin or lame); •before swellings they shoot, or lumps, such hair as: loss, blood or discharges from the nose or mouth; or • abnormal behaviour (loss of fear of people, aggressiveness). If you shoot a sick animal: • Do not cut into diseased parts. • Wash your hands, knives and clothes in hot, soapy animal, and disinfect with a weak bleach solution. water after you finish cutting up and skinning the 2 • If meat from an infected animal can be eaten, cook meat thoroughly until it is no longer pink and juice from the meat is clear. • Do not feed parts of infected animals to dogs. -

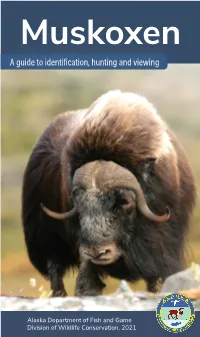

Muskoxen a Guide to Identification, Hunting and Viewing

Muskoxen A guide to identification, hunting and viewing Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation, 2021 Muskoxen A guide to identification, hunting and viewing A Note to Readers The information in this booklet will assist in identifying muskoxen, preparing for a muskox hunting trip, and provide interesting information about muskoxen in Alaska. Details in the Muskox Information section are adapted from the Alaska Wildlife Notebook Series prepared by Tim Smith and revised by John Coady and Randy Kacyon. Alaska Wildlife Notebook Series, © 2008. Many photos in this booklet are provided to aid in understanding of muskoxen and their habitat. Not all images are referenced within the text. Photos that indicate seasons illustrate the significant changes that occur to muskox appearance over the course of the year. Additional information on muskoxen can be found at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) website: www.adfg.alaska.gov Table of Contents Muskox Information Distribution & Physical Attributes . 2 Life History . 4 History in Alaska . 8 Muskoxen and Humans . 10 Identification Identification of Groups . 12 Identification by Age and Sex . 14 Identification Quiz . 20 Hunting Hunter Requirements . 26 Reporting, Trophy Destruction, Labeling . 27 Hunt Information . 28 Planning Your Hunt . 30 Meat Care . 32 Preventing Wounding Loss . 34 From Field to Table . 36 Meat Salvage . 37 Living with Muskox Sharing the Country with Muskoxen . 38 Muskox Information Distribution Muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) are northern animals well adapted to life in the Arctic. At the end of the last ice age, muskoxen were found across northern Europe, Asia, Greenland and North America, including Alaska.