The Role of the Ram in the Impala (Aepyceros Melampus) Mating System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ntinini Controlled Hunting Area

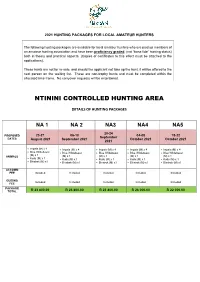

2021 HUNTING PACKAGES FOR LOCAL AMATEUR HUNTERS The following hunting packages are available for local amateur hunters who are paid up members of an amateur hunting association and have been proficiency graded, (not “bona fide” hunting status) both in theory and practical aspects. (Copies of certificates to this effect must be attached to the applications). These hunts are not for re-sale, and should the applicant not take up the hunt, it will be offered to the next person on the waiting list. These are non-trophy hunts and must be completed within the allocated time frame. No carryover requests will be entertained. NTININI CONTROLLED HUNTING AREA DETAILS OF HUNTING PACKAGES NA 1 NA 2 NA3 NA4 NA5 20-24 23-27 06-10 04-08 18-22 PROPOSED September DATES August 2021 September 2021 October 2021 October 2021 2021 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Impala (M) x 4 • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest • Blue Wildebeest (M) x 1 ANIMALS (M) x 1 (M) x 1 (M) x 1 (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Kudu (M) x 1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 • Blesbok (M) x1 ACCOMM FEE Included Included Included Included Included GUIDING Included Included Included Included Included FEE PACKAGE TOTAL R 23 800.00 R 23 800.00 R 23 800.00 R 26 000.00 R 22 000.00 ITHALA CONTROLLED HUNTING AREA DETAILS OF HUNTING PACKAGES IGRA 1 IGRA 2 IGRA 3 IGRA 4 PROPOSED 11-16 02-07 16-21 06-11 DATES June 2021 July 2021 July 2021 August 2021 • Impala -

Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout Has in THIS ISSUE Dbeen Awarded the President’S Cup Letter from the President

DSC NEWSLETTER VOLUME 32,Camp ISSUE 5 TalkJUNE 2019 Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout has IN THIS ISSUE Dbeen awarded the President’s Cup Letter from the President .....................1 for her pending world record East African DSC Foundation .....................................2 Defassa Waterbuck. Awards Night Results ...........................4 DSC’s April Monthly Meeting brings Industry News ........................................8 members together to celebrate the annual Chapter News .........................................9 Trophy and Photo Award presentation. Capstick Award ....................................10 This year, there were over 150 entries for Dove Hunt ..............................................12 the Trophy Awards, spanning 22 countries Obituary ..................................................14 and almost 100 different species. Membership Drive ...............................14 As photos of all the entries played Kid Fish ....................................................16 during cocktail hour, the room was Wine Pairing Dinner ............................16 abuzz with stories of all the incredible Traveler’s Advisory ..............................17 adventures experienced – ibex in Spain, Hotel Block for Heritage ....................19 scenic helicopter rides over the Northwest Big Bore Shoot .....................................20 Territories, puku in Zambia. CIC International Conference ..........22 In determining the winners, the judges DSC Publications Update -

Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus Oryx) Meat Composition on Its Further Technological Processing

CZECH UNIVERSITY OF LIFE SCIENCES PRAGUE Faculty of Tropical AgriSciences Department of Animal Science and Food Processing Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) Meat Composition on its further Technological Processing DISSERTATION THESIS Prague 2018 Author: Supervisor: Ing. et Ing. Petr Kolbábek prof. MVDr. Daniela Lukešová, CSc. Co-supervisors: Ing. Radim Kotrba, Ph.D. Ing. Ludmila Prokůpková, Ph.D. Declaration I hereby declare that I have done this thesis entitled “Influence of Common Eland (Taurotragus oryx) Meat Composition on its further Technological Processing” independently, all texts in this thesis are original, and all the sources have been quoted and acknowledged by means of complete references and according to Citation rules of the FTA. In Prague 5th October 2018 ………..………………… Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to prof. MVDr. Daniela Lukešová CSc., Ing. Radim Kotrba, Ph.D. and Ing. Ludmila Prokůpková, Ph.D., and doc. Ing. Lenka Kouřimská, Ph.D., my research supervisors, for their patient guidance, enthusiastic encouragement and useful critiques of this research work. I am very gratefull to Ing. Petra Maxová and Ing. Eva Kůtová for their valuable help during the research. I am also gratefull to Mr. Petr Beluš, who works as a keeper of elands in Lány, Mrs. Blanka Dvořáková, technician in the laboratory of meat science. My deep acknowledgement belongs to Ing. Radek Stibor and Mr. Josef Hora, skilled butchers from the slaughterhouse in Prague – Uhříněves and to JUDr. Pavel Jirkovský, expert marksman, who shot the animals. I am very gratefull to the experts from the Natura Food Additives, joint-stock company and from the Alimpex-maso, Inc. -

Fitzhenry Yields 2016.Pdf

Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ii DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: March 2016 Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za iii GENERAL ABSTRACT Fallow deer (Dama dama), although not native to South Africa, are abundant in the country and could contribute to domestic food security and economic stability. Nonetheless, this wild ungulate remains overlooked as a protein source and no information exists on their production potential and meat quality in South Africa. The aim of this study was thus to determine the carcass characteristics, meat- and offal-yields, and the physical- and chemical-meat quality attributes of wild fallow deer harvested in South Africa. Gender was considered as a main effect when determining carcass characteristics and yields, while both gender and muscle were considered as main effects in the determination of physical and chemical meat quality attributes. Live weights, warm carcass weights and cold carcass weights were higher (p < 0.05) in male fallow deer (47.4 kg, 29.6 kg, 29.2 kg, respectively) compared with females (41.9 kg, 25.2 kg, 24.7 kg, respectively), as well as in pregnant females (47.5 kg, 28.7 kg, 28.2 kg, respectively) compared with non- pregnant females (32.5 kg, 19.7 kg, 19.3 kg, respectively). -

A National Park in Northern Rhodesia 15

A National Park in Northern Rhodesia 15 A NATIONAL PARK IN NORTHERN RHODESIA By a Proclamation dated 20th April, 1950, the Governor of Northern Rhodesia has established a National Park, to be known as the Kafue National Park. This new park covers some 8,650 square miles roughly in the central Kafue basin, between latitudes 14° and 16° 40' S. It contains a wide range of country from the comparatively drv sandy lands of the south to the big rivers, swamps, and heavy timber of the northern section. The magnificent Kafue River dominates the whole central portion, adding scenic beauty to the attraction of wild life. The park contains representatives of most species of the fauna of Northern Rhodesia. Primates are represented by the Rhodesian Baboon, the Vervet Monkey, and the Greater and Lesser Night-Apes. There are Elephant and Black Rhinoceros, Buffalo, Lion, Leopard, Cheetah, and numbers of the smaller carnivora. Antelope include Eland, Sable, Roan, Liehtenstein's Hartebeest, Blue Wildebeest, Kudu, Defassa Waterbuck, Bushbuck, Reedbuck, Puku, Impala, Oribi, Common, Blue, and Yellow-backed Duikers, Klipspringer, and Sharpe's Stein- buck. There are Red Lechwe and Sitatunga in the Busango Swamp in the north, Hippopotamus in numbers in the Kafue and its larger tributaries. Zebra are common, Warthog and Bushpig everywhere. Birds are abundant. The park is uninhabited apart from certain small settle- ments, on a limited section of the Kafue River, belonging to the indigenous Africans under their tribal chief Kayingu. These people must be accorded their traditional local hunting rights, but such will affect only a small fraction of the whole vast wild area. -

Bulletin of the United States Fish Commission Seattlenwf

THE FUR SEALS AND OTHER LIFE OF THE PRIBILOF ISLANDS, ALASKA, IN 1914 By Wilfred H. Osgood, Edward A. Preble, and George H. Parker I Blank page retained for pagination CONTENTS. Palll!. LgTTERS OF TRANSMITTAL........•...........'............................................. II LETTER OF SUBMITTAL................... ................................................. 12 INTRODUCTION............... .. 13 Personnel and instructions. ............................................................. 13 Investigations by Canada and Japan... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. IS Itinerary , .. " . .. IS Impartial nature of the investigation " '" . 16 Acknowledgments................. 16 THg PRIBILOF ISLANDS..................................................................... 17 General description...................... .. 17 Vegetation. 18 Climate............. 18 CHARACTER AND HABITS OF THE FUR SEAL IN BRIEF....... ................................. 18 G'eneral characteristics. ................ .. .............................................. 18 Range.................................................................................. 18 , Breeding habits ; ........................ 19 Habits of bachelors : ......................... 20 Age of seals... ;. ....................................................................... 20 SEALING HISTORY IN BRIEF................................................................. 21 Russian management " .. .. 21 American occupation and the leasing system : . .. ... 21 The growth of pelagic sealing , "".. .. .. .. 22 The Paris Tribunal -

Connochaetes Gnou – Black Wildebeest

Connochaetes gnou – Black Wildebeest Blue Wildebeest (C. taurinus) (Grobler et al. 2005 and ongoing work at the University of the Free State and the National Zoological Gardens), which is most likely due to the historic bottlenecks experienced by C. gnou in the late 1800s. The evolution of a distinct southern endemic Black Wildebeest in the Pleistocene was associated with, and possibly driven by, a shift towards a more specialised kind of territorial breeding behaviour, which can only function in open habitat. Thus, the evolution of the Black Wildebeest was directly associated with the emergence of Highveld-type open grasslands in the central interior of South Africa (Ackermann et al. 2010). Andre Botha Assessment Rationale Regional Red List status (2016) Least Concern*† This is an endemic species occurring in open grasslands in the central interior of the assessment region. There are National Red List status (2004) Least Concern at least an estimated 16,260 individuals (counts Reasons for change No change conducted between 2012 and 2015) on protected areas across the Free State, Gauteng, North West, Northern Global Red List status (2008) Least Concern Cape, Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal TOPS listing (NEMBA) (2007) Protected (KZN) provinces (mostly within the natural distribution range). This yields a total mature population size of 9,765– CITES listing None 11,382 (using a 60–70% mature population structure). This Endemic Yes is an underestimate as there are many more subpopulations on wildlife ranches for which comprehensive data are *Watch-list Threat †Conservation Dependent unavailable. Most subpopulations in protected areas are stable or increasing. -

MOVEMENTS, HABITAT USE, and ACTIVITY PATTERNS of a TRANSLOCATED GROUP of ROOSEVELT ELK by Matthew Mccoy a Thesis Prese

MOVEMENTS, HABITAT USE, AND ACTIVITY PATTERNS OF A TRANSLOCATED GROUP OF ROOSEVELT ELK by Matthew McCoy A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science June, 1 986 MOVEMENTS, HABITAT USE, AND ACTIVITY PATTERNS OF A TRANSLOCATED GROUP OF ROOSEVELT ELK by Matthew McCoy A F gam Director, Natural Resources Graduate Program 86/W-66/06/10 Natural Resources Graduate Program Number Ala M. Gillespi9( ABSTRACT In March 1982, 17 Roosevelt elk (Cervus elaphus roosevelti) were captured at Gold Bluffs Beach, Humboldt County, California and translocated to an enclosure 4 km east of Shelter Cove, Humboldt County. The animals were released from the enclosure in November 1982. Data were collected for eight radio-collared animals (seven adult females and one 4-year old male) January to December 1983. The number of herds varied from one (January through March) to four (October through December). Three female herds moved 45 km, 58 km, and 84 km south of Shelter Cove, while the radio-collared male remained within 16 km of Shelter Cove. Home range locations varied seasonally. Home range sizes were largest during the summer reflecting migrational and exploratory movements. Habitat use was disproportionate to habitat availability at the home range level during each season. Cultivated grasslands and riparian areas were used in proportions greater than their availability. Coastal Prairie use was greater than that available except in the Shelter Cove area. Shrub and forest habitat types were generally used less than that available. Animal distances to nearest road and water varied seasonally, but were greatest for radio-collared females during the spring. -

Animals of Africa

Silver 49 Bronze 26 Gold 59 Copper 17 Animals of Africa _______________________________________________Diamond 80 PYGMY ANTELOPES Klipspringer Common oribi Haggard oribi Gold 59 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Copper 17 Bronze 26 Silver 49 Gold 61 Copper 17 Diamond 80 Diamond 80 Steenbok 1 234 5 _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________ Cape grysbok BIG CATS LECHWE, KOB, PUKU Sharpe grysbok African lion 1 2 2 2 Common lechwe Livingstone suni African leopard***** Kafue Flats lechwe East African suni African cheetah***** _______________________________________________ Red lechwe Royal antelope SMALL CATS & AFRICAN CIVET Black lechwe Bates pygmy antelope Serval Nile lechwe 1 1 2 2 4 _______________________________________________ Caracal 2 White-eared kob DIK-DIKS African wild cat Uganda kob Salt dik-dik African golden cat CentralAfrican kob Harar dik-dik 1 2 2 African civet _______________________________________________ Western kob (Buffon) Guenther dik-dik HYENAS Puku Kirk dik-dik Spotted hyena 1 1 1 _______________________________________________ Damara dik-dik REEDBUCKS & RHEBOK Brown hyena Phillips dik-dik Common reedbuck _______________________________________________ _______________________________________________African striped hyena Eastern bohor reedbuck BUSH DUIKERS THICK-SKINNED GAME Abyssinian bohor reedbuck Southern bush duiker _______________________________________________African elephant 1 1 1 Sudan bohor reedbuck Angolan bush duiker (closed) 1 122 2 Black rhinoceros** *** Nigerian -

Engl South Africa Limpopo, Game Reserves & Brandberg 2017

South Africa 2017 - Limpopo , Game Reserve s & Brandberg - Office Germany: Office Austria: Ziegelstadel 1 · D-88316 Isny Europastrasse 1/1 · A-7540 Güssing Phone.: +49 (0) 75 62 / 914 54 - 14 Phone: +43 (0) 33 22 / 42 963 - 0 www.blaser-safaris.com Fax.: +43 (0) 33 22 / 42 963 - 59 [email protected] Hunt in South In South Africa, safaris can be conducted throughout the year; however the best time Africa : for a safari is between April & October. Some 40 different species of game can be hunted across the country, but each safari is individually planned to give you maximum enjoyment & satisfaction. The safari is suitable for the whole family, for non-hunters; there are a variety of inter- esting, photographic tours. All wildlife species listed in the price list are hunted on farmland / hunting areas around the lodge. LIMPOPO Limpopo The area of our partner Wayne Wagner Safaris is located in Hoedspruit Limpopo Pro v- ince and is situated between Phalaborwa, Gravelotte and Mica on the Olifants River. Accommodation To be sure that the safari meets with your specific requirements a questionnaire will be for Limpopo & completed before your arrival with your personal details, species to be hunted, food Games Reserves preferences and accommodation requirements. - 2 - Prices 201 7 5 DAY SOUTH AFRICAN PLAINS GAME CULLING PACKAGE The following package is a cull hunt for certain plains game species. This package includes 5 full days of hunting; you must plan on arriving one day prior to commencement of the safari. The hunt will take place in the bushveld region of the Limpopo Province near the town of Hoedspruit. -

The Effect of Species Associations on the Diversity and Coexistence of African Ungulates

The effect of species associations on the diversity and coexistence of African ungulates. By Nancy Barker For Professor Kolasa BIO306H1 – Tropical Ecology University of Toronto Wednesday, August 24th, 2005 Abstract: The effects of species associations on species diversity and coexistence were investigated in East Africa. The frequency and group sizes of African ungulates were observed and analyzed to determine for differences in species associations based on their density and distribution, as well as their associations with other species. Associations between species were determined to be nonrandom and seen to affect the demographics of associating herds. Such associations mirrored in other studies were shown to be the result of interspecific competition, habitat preferences and predation pressure which increases the potential for coexistence between species. This suggests a potentially important role in the regulation of species diversity by ecological dynamics in species rich communities. In the face of today’s biodiversity crisis, such understanding of species associations and how they are regulated may have huge implications for conservation. Introduction: known with the famous Darwin’s finches of the Galapagos Islands. However, there are many other Sympatric coexistence of organisms within a guilds with what seems to be extensive community poses several questions for ecologists. overlapping in their resources, such as the grazing High levels of species association occur with high herds in Africa which eat common and widely species packing, as is seen within the Selous game dispersed foods. Sinclair (Sinclair, 1979 as cited in reserve of Tanzania in east Africa. Sinclair (1985) Sinclair, 1985) has found that this seemingly notes that mixed herds are frequently seen in east extensive overlap among these herds have also Africa and Connor and Simberloff (1979) have undergone niche separation. -

A Study of How Dominance Rank Within a Herd of Resident Burchell’S Zebra (Equus Burchelli) at Ndarakwai Ranch Correlate to Frequencies of Other Behaviors

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2010 Seeing Stripes: A Study of How Dominance Rank Within a Herd of Resident Burchell’s Zebra (Equus Burchelli) at Ndarakwai Ranch Correlate to Frequencies of Other Behaviors. Alexandra Clayton SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Zoology Commons Recommended Citation Clayton, Alexandra, "Seeing Stripes: A Study of How Dominance Rank Within a Herd of Resident Burchell’s Zebra (Equus Burchelli) at Ndarakwai Ranch Correlate to Frequencies of Other Behaviors." (2010). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 899. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/899 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing Stripes A study of how dominance rank within a herd of resident Burchell’s zebra (Equus burchelli) at Ndarakwai Ranch correlate to frequencies of other behaviors. Alexandra Clayton Advisor: Reese Matthews SIT Wildlife Conservation and Political Ecology Fall 2010 Acknowledgements There are so many people that made this project possible, but I would first like to thank Peter Jones for allowing me the chance to conduct my study at Ndarakwai, and for allowing two Internet- starved students to use your wireless! It is a beautiful place and I hope to return someday. I also want to thank Thomas for letting us camp outside his house and to Bahati for making us the best chapatti and ginger tea we’ve ever had, and for washing our very muddy clothes.