Corps of Royal Engineers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Valuing the Heritage of the Channel Islands

Valuing the Heritage of the Channel Islands Kate Clark Kate Clark Associates Heritage policy, practice & planning Elizabeth Castle, Jersey Valuing the Heritage of the Channel Islands An initial assessment against World Heritage Site criteria and Public Value criteria Kate Clark Kate Clark Associates For Jersey Heritage August 2008. List of Contents Acknowledgements 6 Introduction 7 Summary Recommendations 8 Recommendation One: Do more to capture the value of Jersey’s Heritage Recommendation Two: Explore a World Heritage bid for the Channel Islands Chapter One - Valuing heritage 11 1.1 Gathering data about heritage 1.2 Research into the value of heritage 1.3 Public value Chapter Two – Initial assessment of the heritage of the Channel Islands 19 2.1 Introduction 2.2 Geography and politics 2.3 Brief history 2.4 Historic environment 2.5 Intangible heritage 2.6 Heritage management in the Channel Islands 2.7 Issues Chapter Three – capturing the value of heritage in the Channel Islands 33 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Intrinsic value 3.3 Instrumental benefits 3.4 Institutional values 3.5 Recommendations 4 Chapter Four – A world heritage site bid for the Channel Islands 37 4.0 Introduction 4.1 World heritage designation 4.2 The UK tentative list 4.3 The UK policy review 4.4 A CI nomination? 4.5 Assessment against World Heritage Criteria 4.6 Management criteria 4.7 Recommendations Conclusions 51 Appendix One – Jersey’s fortifications 53 A 1.1 Historic fortifications A 1.2 A brief history of fortification in Jersey A 1.3 Fortification sites A 1.4 Brief for further work Appendix Two – the UK Tentative List 67 Appendix Three – World Heritage Sites that are fortifications 71 Appendix Four – assessment of La Cotte de St Brelade 73 Appendix Five – brief for this project 75 Bibliography 77 5 Acknowledgements This report would not have been possible without the very kind support, enthusiasm, time and hospitality of John Mesch and his colleagues of the Société Jersiase, including Dr John Renouf and John Stratford. -

Peat Database Results Hampshire

Baker's Rithe, Hampshire Record ID 29 Authors Year Allen, M. and Gardiner, J. 2000 Location description Deposit location SU 6926 1041 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Preserved timbers (oak and yew) on peat ledge. One oak stump in situ. Peat layer 0.15-0.26 m deep [thick?]. Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available -1 m OD Yes Notes 14C details ID 12 Laboratory code R-24993/2 Sample location Depth of sample Dated sample description [-1 m OD] Oak stump Age (uncal) Age (cal) Delta 13C 3735 ± 60 BP 2310-1950 cal. BC Notes Stump BB Bibliographic reference Allen, M. and Gardiner, J. 2000 'Our changing coast; a survey of the intertidal archaeology of Langstone Harbour, Hampshire', Hampshire CBA Research Report 12.4 Coastal peat resource database (Hazell, 2008) Page 1 of 86 Bury Farm (Bury Marshes), Hampshire Record ID 641 Authors Year Long, A., Scaife, R. and Edwards, R. 2000 Location description Deposit location SU 3820 1140 Deposit description Deposit stratigraphy Associated artefacts Early work Sample method Depth of deposit 14C ages available Yes Notes 14C details ID 491 Laboratory code Beta-93195 Sample location Depth of sample Dated sample description SU 3820 1140 -0.16 to -0.11 m OD Transgressive contact. Age (uncal) Age (cal) Delta 13C 3080 ± 60 BP 3394-3083 cal. BP Notes Dark brown humified peat with some turfa. Bibliographic reference Long, A., Scaife, R. and Edwards, R. 2000 'Stratigraphic architecture, relative sea-level, and models of estuary development in southern England: new data from Southampton Water' in ' and estuarine environments: sedimentology, geomorphology and geoarchaeology', (ed.s) Pye, K. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

Thompson, Mark S. (2009) the Rise of the Scientific Soldier As Seen Through the Performance of the Corps of Royal Engineers During the Early 19Th Century

Thompson, Mark S. (2009) The Rise of the Scientific Soldier as Seen Through the Performance of the Corps of Royal Engineers During the Early 19th Century. Doctoral thesis, University of Sunderland. Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/3559/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF THE SCIENTIFIC SOLDIER AS SEEN THROUGH THE PERFORMANCE OF THE CORPS OF ROYAL ENGINEERS DURING THE EARLY 19TH CENTURY. Mark S. Thompson. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Sunderland for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. February 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS. Table of Contents.................................................................................................ii Tables and Figures. ............................................................................................iii List of Appendices...............................................................................................iv Abbreviations .....................................................................................................v Abstract ....................................................................................................vi Acknowledgements............................................................................................vii SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION......................................................................... 1 1.1. Context ................................................................................................. -

Mapmaking in England, Ca. 1470–1650

54 • Mapmaking in England, ca. 1470 –1650 Peter Barber The English Heritage to vey, eds., Local Maps and Plans from Medieval England (Oxford: 1525 Clarendon Press, 1986); Mapmaker’s Art for Edward Lyman, The Map- world maps maker’s Art: Essays on the History of Maps (London: Batchworth Press, 1953); Monarchs, Ministers, and Maps for David Buisseret, ed., Mon- archs, Ministers, and Maps: The Emergence of Cartography as a Tool There is little evidence of a significant cartographic pres- of Government in Early Modern Europe (Chicago: University of Chi- ence in late fifteenth-century England in terms of most cago Press, 1992); Rural Images for David Buisseret, ed., Rural Images: modern indices, such as an extensive familiarity with and Estate Maps in the Old and New Worlds (Chicago: University of Chi- use of maps on the part of its citizenry, a widespread use cago Press, 1996); Tales from the Map Room for Peter Barber and of maps for administration and in the transaction of busi- Christopher Board, eds., Tales from the Map Room: Fact and Fiction about Maps and Their Makers (London: BBC Books, 1993); and TNA ness, the domestic production of printed maps, and an ac- for The National Archives of the UK, Kew (formerly the Public Record 1 tive market in them. Although the first map to be printed Office). in England, a T-O map illustrating William Caxton’s 1. This notion is challenged in Catherine Delano-Smith and R. J. P. Myrrour of the Worlde of 1481, appeared at a relatively Kain, English Maps: A History (London: British Library, 1999), 28–29, early date, no further map, other than one illustrating a who state that “certainly by the late fourteenth century, or at the latest by the early fifteenth century, the practical use of maps was diffusing 1489 reprint of Caxton’s text, was to be printed for sev- into society at large,” but the scarcity of surviving maps of any descrip- 2 eral decades. -

The Royal Engineers Journal

_ _I_·_ 1__ I _ _ _ __ ___ The Royal Engineers Journal. Sir Charles Paley . Lieut.-Col. P. H. Keay 77 Maintenance of Landing Grounds . A. Lewis-Dale, Esq. 598 The Combined Display, Royal Tournament, 1930 Bt. Lieut.-Col. N. T. Fitzpatrik 618 Restoration of Whitby Water Supply . Lieut. C. E. Montagu 624 Notes on the Engineers in the U.S. Army . "Ponocrates" 629 A Subaltern in the Indian Mutiny, Part I . Bt. CoL C. B. Thackeray 683 The Kelantan Section of the East Coast Railway, F.M.S.R. Lieut. Ll. Wansbrough-Jones 647 The Reconstruction of Tidworth Bridge by the 17th Field Company, R.E., in April, 1930 . Lient. W. B. Sallitt 657 The Abor Military and Political Mission, 1912-13. Part m. Capt. P. G. Huddlestcn 667 Engineer Units of the Officers' Training Corps . Major D. Portway 676 Some Out-of-the-Way Places .Lieut.-CoL L. E. Hopkins 680 " Pinking" . Capt. K. A. Lindsay 684 Office Organization in a Small Unit . Lieut. A. J. Knott 691 The L.G.O.C. Omnibus Repair Workshop at Chiswick Park Bt. Major G. MacLeod Ross 698 Sir Theo d'O Lite and the Dragon .Capt. J. C. T. Willis 702 Memoirs.-Wing-Commander Bernard Edward Smythies, Lieut.-Col. Sir John Norton-Griffiths . 705 Sixty Years Ago. 0 Troop-Retirement Scheme. 712 Books. Magazines. Correspondence. 714 VOL. XLIV. DECEMBER, 1930. CHATHAM: Tun INSTITUTION OF ROYAL ENGINZZBS. TZLEPHONZ: CHATHAM, 2669. AGZNTS AND PRINTERS: MACZAYS LTD. All it tt EXPAMET EXPANDED METAL Specialities "EXPAMET" STEEL SHEET REINFORCEMENT FOR CONCRETE. "EXPAMET" and "BB" LATHINGS FOR PLASTERWORK. -

Solent Defences Map.Ai

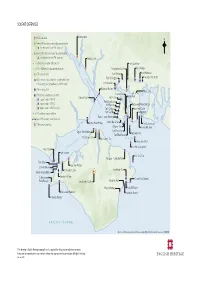

SOLENT DEFENCES Southampton Medieval castle N Henry VIII circular or centrally planned castle ( modernised in the 19th century) Henry VIII castle influenced by angle bastion ( modernised in the 19th century) Netley Castle 16th-century bastioned enceinte Fort Southwick 17th–18th-century bastioned enceinte Portchester Castle Fort Widley 17th-century fort Fort Nelson Fort Purbrook S Fort Wallington Farlington Redoubt 18th-century bastioned fort, modernised in the O U T 19th-century and operational in WW1 and 2 H Fort Fareham A M P Bungalow Battery 19th-century fort T O Hilsea Lines N Charles Fort 19th-century battery or sea fort James Fort Calshot Castle Fort Elson ( operational in WW1) W A T Fort Brockhurst ( operational in WW2) E R Fort Rowner Portsmouth Point Battery ( operational in WW1 and 2) Fort Grange Southsea Castle 19th-century bastioned line Fort Gomer Lumps Fort Brown Down Battery Late 19th-century boom defence Stokes Bay Lines 20th-century defence Stone Point Battery Fort Cumberland Gilkicker Fort Eastney Batteries Fort Monckton Egypt Point Battery Spitbank Fort Fort Blockhouse West Cowes Fort East Cowes Fort SPITHEAD N T L E Horse Sand Fort S O E T H No Man’s Land Fort Hurst Castle Fort Victoria St Helen’s Fort Puckpool Mortar Battery Fort Albert Bouldner Battery Cliff End Battery Yarmouth Castle Bembridge Fort Warden Point Battery Golden Hill Fort Hatherwood Culver Point Battery Point Battery Carisbrooke Castle Sandown Fort Barrack Battery Redcliff Battery Freshwater Redoubt Yaverland Battery Needles Battery ENGLISH CHANNEL Based upon Ordnance Survey data. © Crown copyright 2006. All rights reserved. Licence no. -

Military HEAP for the Isle of Wight

Island Heritage Service Historic Environment Action Plan Military Type Report Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service April 2010 01983 823810 Archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com Military HEAP for the Isle of Wight 1.0 INTRODUCTION Page 3 2.0 ASSESSMENT OF THE HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT Page 4 2.1 Location, Geology and Topography Page 4 2.2 The Nature of the Historic Environment Resource Page 4 2.3 The Island’s HEAP overview document Page 4 3.0 DEFINING MILITARY STATUS Page 5 4.0 ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT OF MILITARY/DEFENCE Page 5 ASSETS 4.1 Principle Historical Processes Page 5 4.2 Surviving Archaeology and Built Environment Page 7 4.3 Relationship with other HEAP Types Page 21 4.4 Contribution of Military/Defence Type to Isle of Wight Historic Page 22 Environment and Historic Landscape Character 4.5 Values, Perceptions and Associations Page 22 4.6 Resources Page 23 4.7 Accessibility and Enjoyment Page 24 4.8 Heritage Assets of Particular Significance Page 26 5.0 CONSERVATION AND MANAGEMENT Page 28 5.1 Forces for Change Page 28 5.2 Management Issues Page 30 5.3 Conservation Designation Page 31 6.0 FUTURE MANAGEMENT Page 33 7.0 GLOSSARY OF TERMS Page 34 8.0 REFERENCES Page 36 2 Iwight.com 1.0 INTRODUCTION The Isle of Wight Historic Environment Action Plan (HEAP) consists of a set of general documents, 15 HEAP Area Reports and a number of HEAP Type reports which are listed in the table below: General Documents HEAP Area Reports HEAP Type Reports HEAP Map of Areas Arreton Valley Agricultural Landscapes HEAP Introduction -

Fortress Study Group Library Catalogue

FSG LIBRARY CATALOGUE OCTOBER 2015 TITLE AUTHOR SOURCE PUBLISHER DATE PAGE COUNTRY CLASSIFICATION LENGTH "Gibraltar of the West Indies": Brimstone Hill, St Kitts Smith, VTC Fortress, no 6, 24-36 1990 West Indies J/UK/FORTRESS "Ludendorff" fortified group of the Oder-Warthe-Bogen front Kedryna, A & Jurga, R Fortress, no 17, 46-58 1993 Germany J/UK/FORTRESS "Other" coast artillery posts of southern California: Camp Haan, Berhow, MA CDSG News Volume 4, 1990 2 USA J/USA/CDSG 1 Camp Callan and Camp McQuaide Number 1, February 1990 100 Jahre Gotthard-Festung, 1885-1985 : Geschichte und Ziegler P GBC, Basel 1986 Switzerland B Bedeutung unserer Alpenfestung [100 years of the Gotthard Fortress, 1885-1985 : history and importance of our Alpine Fortress] 100 Jahre Gotthard-Festung, 1885-1985 : Geschichte und Ziegler P 1995 Switzerland B Bedeutung unserer Alpenfestung [100 years of the Gotthard Fortress, 1885-1985 : history and importance of our Alpine Fortress] 10thC castle on the Danube Popa, R Fortress, no 16, 16-24 1993 Bulgaria J/UK/FORTRESS 12-Inch Breech Loading Mortars Smith, BW CDSG Journal Volume 7, 1993 2 USA J/USA/CDSG 1 Issue 3, November 1993 13th Coast Artillery (Harbor Defense) Regiment Gaines, W CDSG Journal Volume 7, 1993 10 USA J/USA/CDSG 1 Issue 2, May 1993 14th Coast Artillery (Harbor Defense) Regiment, An Organizational Gaines, WC CDSG Journal Volume 9, 1995 17 USA J/USA/CDSG 2 History, The Issue 3, August 1995 16-Inch Batteries at San Francisco and The Evolution of The Smith B Coast Defense Journal 2001 68 USA J/USA/CDSG 2 Casemated 16-Inch Battery, The Volume 15, Issue 1, February 2001 180 Mm Coast Artillery Batteries Guarding Vladivostok,1932-1945 Kalinin, VI et al Coast Defense Journal 2002 25 Russia J/USA/CDSG 2 Part 2: Turret Batteries Volume 16, Issue 1, February 2002 180mm Coast Artillery Batteries Guarding Vladivostok, Russia, Kalinin, VI et al Coast Defense Journal 2001 53 Russia J/USA/CDSG 2 1932-1945: Part 1. -

Military Aspects of Hydrogeology: an Introduction and Overview

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Military aspects of hydrogeology: an introduction and overview JOHN D. MATHER* & EDWARD P. F. ROSE Department of Earth Sciences, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK *Corresponding author (e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: The military aspects of hydrogeology can be categorized into five main fields: the use of groundwater to provide a water supply for combatants and to sustain the infrastructure and defence establishments supporting them; the influence of near-surface water as a hazard affecting mobility, tunnelling and the placing and detection of mines; contamination arising from the testing, use and disposal of munitions and hazardous chemicals; training, research and technology transfer; and groundwater use as a potential source of conflict. In both World Wars, US and German forces were able to deploy trained hydrogeologists to address such problems, but the prevailing attitude to applied geology in Britain led to the use of only a few, talented individuals, who gained relevant experience as their military service progressed. Prior to World War II, existing techniques were generally adapted for military use. Significant advances were made in some fields, notably in the use of Norton tube wells (widely known as Abyssinian wells after their successful use in the Abyssinian War of 1867/1868) and in the development of groundwater prospect maps. Since 1945, the need for advice in specific military sectors, including vehicle mobility, explosive threat detection and hydrological forecasting, has resulted in the growth of a group of individuals who can rightly regard themselves as military hydrogeologists. -

Divine Display Or Secular Science

Divine Display or Secular Science: Defining Nature at the Natural History Museum in London Author(s): Carla Yanni Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 55, No. 3 (Sep., 1996), pp. 276-299 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural Historians Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/991149 Accessed: 21-08-2016 19:45 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Society of Architectural Historians, University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians This content downloaded from 128.59.106.243 on Sun, 21 Aug 2016 19:45:58 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms Divine Display or Secular Science Defining Nature at the Natural History Museum in London Owen was the premier reconstructive anatomist in Victorian CARLA YANNI, University of New Mexico England, and he was later known as an opponent of Darwinism. His first job at the British Museum, which at the time held the Conflicting ranging from definitions nature as the unwritten of nature Book of God in to the Victorian age, natural history collections, was to secure government funds for nature as secular science, affected the architectural develop- them, and to persuade Parliament to allow the division of the ment of the Natural History Museum in London. -

Records of the 4Th International Coilloquy on Military History

COMMISSION INTERNATIONALE D'HISTOIRE MILITAIRE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF MILITARY HISTORY INTERNATIONALE KOMMISSION FUR MILITARGESCHICHTE ACTA No. 4 OTTAWA 23-25 VIII 1978 Actes du 4e Colloque International d'Histoire Militaire Records of the 4th International Colloquy on Military History Verhandlungen der 4 Internationalen Tagung für Militärgeschichte Ottawa 1979 OTTAWA OTTAWA 23-25 VIII 1978 Published with the support of the Department of National Defence of Canada Publié avec le concours du Ministère de la Défense nationale du Canada Herausgegeben mit Mitwirkung des Kanadische Ministeriums des Verteidigung COMMISSION INTERNATIONALE D'HISTOIRE MILITAIRE INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION OF MILITARY HISTORY INTERNATIONALE KOMMISSION FUR MILITARGESCHICHTE ACTA No. 4 OTTAWA 23.25 VIII 1978 Actes du 4e Colloque International d'Histoire Militaire Records of the 4th International Colloquy on Military History Verhandlungen der 4 Internationalen Tagung für Militärgeschichte Ottawa 1979 OTTAWA TABLES DES MATIÈRES INHALTSVERZEICHNIS CONTENTS Page Introduction by Dr. W.A.B. Douglas, Director of History, Department of National Defence, and chairman, Program Committee i Welcome to delegates by His Excellency, the Hon. Jules Leger, Governor General of Canada xiv Opening Remarks by Admiral R.H. Falls, Chief of the Defence Staff xvi PLENARY SESSION: S.F. Wise, The Employment of Indians during the American Revolution: British Military Attitudes 1 J. Shy, Armed Force in Colonial North America: New Spain, New France and Anglo-America 10 J. Vidalenc, La France et le bloc africain, 1830-1934 27 WORKSHOPS: B.F. Cooling, Imperial Echoes, 1492-1776: A New Look at the Roles of Armed Forces in Colonial America 42 R. Higham, Military Frontiersmanship: A Hypothesis from the point of view of the Encroacher 53 Shu Kohno, A Study of the Creation, Development and Characteristics of the Chinese Red Army - An Example of a Liberation Army Created in a Semi-Colony 62 F.