Applied Computer Technology in Cree and Naskapi Language Programs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Inuit

TOPIC 6.5 When Newfoundland and Labrador joined Confederation in 1949, whose responsibility was it to make provisions for Aboriginals? Will modern technology help or hinder Aboriginal groups in the preservation of their culture? 6.94 School children in front of the Grenfell Mission plane, Nain, 1966 Introduction When Newfoundland and Labrador joined and other services to Inuit communities. But unlike Confederation in 1949, the Terms of Union between the Moravians, who tried to preserve Inuit language the two governments made no reference to Aboriginal and culture, early government programs were not peoples and no provisions were made to safeguard their concerned with these matters. Teachers, for example, land or culture. No bands or reserves existed in the new delivered lessons in English, and most health and province and its Aboriginal peoples did not become other workers could not speak Inuktitut. registered under the federal Indian Act. Schooling, which was compulsory for children, had a Inuit huge influence on Inuit culture. The curriculum taught At the time of Confederation, at least 700 Inuit lived students nothing about their culture or their language, so in Labrador. Aside from their widespread conversion both were severely eroded. Many dropped out of school. to Christianity, many aspects of Inuit culture were Furthermore, young Inuit who were in school in their intact – many Inuit still spoke Inuktitut, lived on formative years did not have the opportunity to learn their traditional lands, and maintained a seasonal the skills to live the traditional lifestyle of their parents subsistence economy that consisted largely of hunting and grandparents and became estranged from this way and fishing. -

Aborlit Algonquian Eastern Canada 20080411

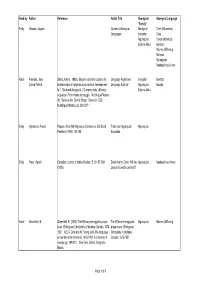

Read by Author Reference Article Title Aboriginal Aboriginal Language "Family" Emily Maurais, Jaques Quebec's Aboriginal Aboriginal Cree (Atikamekw) Languages Iroquoian Cree Algonquian Huron (Wyandot) Eskimo-Aleut Inuktitut Micmac (Mi’kmaq) Mohawk Montagnais Naskapi-Innu-Aimun Karlie Freeland, Jane Stairs, Arlene. 1988a. Beyond cultural inclusion: An Language Rights and Iroquoian Inuktitut Donna Patrick Inuit example of indigenous educational development. Language Survival Algonquian Inupiaq In T. Skutnabb-Kangas & J. Cummins (eds.) Minority Eskimo-Aleut education: From shame to struggle. Multilingual Matters 40. Series editor Derrick Sharp. Clevedon, G.B.: Multilingual Matters, pp. 308-327. Emily Hjartarson, Freida Papers of the 26th Algonquin Conference. Ed. David Traditional Algonquian Algonquian Pentland (1995): 151-168 Education Emily Press, Harold Canadian Journal of Native Studies 15 (2) 187-209 Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Algonquian Naskapi-Innu-Aimun (1995) Lessons Ever be Learned? Karlie Greenfield, B. Greenfield, B. (2000) The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic prayer The Mi’kmaq hieroglyphic Algonquian Micmac (Mi’kmaq) book: Writing and Christianity in Maritime Canada, 1675- prayer book: Writing and 1921. In E.G. Gray and N. Fiering (eds) The language Christianity in Maritime encounter in the Americas, 1492-1800: A collection of Canada, 1675-1921 essays (pp. 189-211). New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books. Page 1 of 9 Majority Relevant Area Specific Area Age Time Period Discipline of Research Type of Language Research French Canada Quebec -

The Rossville Scandal, 1846: James Evans, the Cree, and a Mission on Trial by Raymond Moms S Hirri Tt -Beaumont, B.A

The Rossville Scandal, 1846: James Evans, the Cree, and a Mission on Trial by Raymond Moms S hirri tt -Beaumont, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Joint Master's Programme University of Manitoba and University of Winnipeg January 200 1 National Library Biblioth&que nationale I*i of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingtm Ottawa ON K1A ON4 -ON KIAM Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une Licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive permettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seii reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels rnay be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. THE UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ****+ COPYRiGET PERMISSION PAGE The Rossville Scandal, 1846: James Evans, the Cree, and r Mission on Trial -

1996 Matthewson Reinholtz.Pdf

211 TIlE SYNTAX AND SEMANTICS OF DETERMINERS:' (2) OP A COMPARISON OF SALISH AND CREEl /~ Specifier 0' Lisa Matthewson, UBC and SCES/SFU Charlotte Reinholtz, University of Manitoha o/"" NP I ~ the coyote 1. Introduction According to the OP-analysis, the determiner is the head of the phrase and takes NP as its The goal of this paper is to provide a comparative analysis of determiners in Salish languages complement. 0 is a functional head, which selects a lexical projection (NP) as its complement. and in Cree. We will show that there are considerable surface differences between Salish and The lexical/functional split is summarized in (3): Cree, both in the syntax and the semantics of the determiners. However, we argue that these differences can and should be treated as part of a restricted range of cross-linguistic variation (3) If X" E {V, N, P, A}, then X" is a Lexical head (open-class element). within a universally-provided OP (Determiner Phrase)-system. If X" E {Tense, Oet, Comp, Case}, then X" is a Functional head (closed-class element). The paper is structured as follows. We first provide an introduction to relevant theoretical ~haine 1993:2) proposals about the syntax and semantics of determiners. Section 2 presents an analysis of Salish determiners, and section 3 presents an analysis of Cree determiners. The two systems are briefly A major motivation for the OP-analysis of noun phrases comes from the many parallels between compared and contrasted in section 4. clauses and noun phrases. For example, Abney (1987) notes that many languages contain agreement within noun phrases which parallels agreement at the clausal level. -

Obviation in Michif Deborah Weaver

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects 8-1-1982 Obviation in Michif Deborah Weaver Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/theses Recommended Citation Weaver, Deborah, "Obviation in Michif" (1982). Theses and Dissertations. 672. https://commons.und.edu/theses/672 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, and Senior Projects at UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OBVIATION IN MICHIF by Deborah Weaver Bachelor of Science, Wheaton College, 1976 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of North Dakota in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Grand Forks, North Dakota August 1982 -s J 1 I This thesis submitted by Deborah Weaver in partial ful fillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts from the University of North Dakota is hereby approved by the Faculty Advisory Committee under whom the work has been done. This thesis meets the standards for appearance and con forms to the style and format requirements of the Graduate School of the University of North Dakota, and is hereby ap proved . ( I W k i 11 Title OBVIATION IN MICHIF Department Linguistics Degree Master of Arts In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a graduate degree from the Uni versity of North Dakota, I agree that the Library of this University shall make it freely available for in spection. -

Davis Inlet in Crisis: Will the Lessons Ever Be Learned?

DAVIS INLET IN CRISIS: WILL THE LESSONS EVER BE LEARNED? Harold Press P.O. Box 6342, Station C St. John's, Newfoundland Canada, A1C 6J9 Abstract / Resume The author reviews the history of the Mushuau Innu who now live at Davis Inlet on the Labrador coast. He examines the policy context of the contem- porary community and looks at the challenges facing both the Innu and governments in the future. L'auteur réexamine l'histoire des Mushuau Innu qui habitent à présent à Davis Inlet sur la côète de Labrador. Il étudie la politique de la communauté contemporaine et considère les épreuves qui se présenteront aux Innu et aux gouvernements dans l'avenir. 188 Harold Press We have only lived in houses for twenty-five years, and we have seldom asked ourselves, "what should an Innu commu- nity be like? What does community mean to us as a people whose culture is based in a nomadic past, in six thousand years of visiting every pond and river valley in Nitassinan? - Hearing the Voices While the front pages of our local newspapers are replete with accounts of violence, poverty and abuse throughout the world, not often do we encounter cases, particularly in this country, of such unconditional destruc- tion that have led to the social disintegration of entire communities. One such case was Grassy Narrows, starkly and movingly brought to our collective attention by Shkilnyk (1985). The story of Grassy Narrows is one of devastation, impoverishment, and ruin. Shkilnyk describes her experi- ences in the small First Nation's community this way: I could never escape the feeling that I had been parachuted into a void - a drab and lifeless place in which the vital spark of life had gone out. -

The Evolution of Health Status and Health Determinants in the Cree Region (Eeyou Istchee)

The Evolution of Health Status and Health Determinants in the Cree Region (Eeyou Istchee): Eastmain 1-A Powerhouse and Rupert Diversion Sectoral Report Volume 1: Context and Findings Series 4 Number 3: Report on the health status of the population Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay The Evolution of Health Status and Health Determinants in the Cree Region (Eeyou Istchee): Eastmain-1-A Powerhouse and Rupert Diversion Sectoral Report Volume 1 Context and Findings Jill Torrie Ellen Bobet Natalie Kishchuk Andrew Webster Series 4 Number 3: Report on the Health Status of the Population. Public Health Department of the Cree Territory of James Bay Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay. Authors Jill Torrie Cree Board of Health & Social Services of James Bay (Montreal) [email protected] Ellen Bobet Confluence Research and Writing (Gatineau) [email protected] Natalie Kishchuk Programme evaluation and applied social research consultant (Montreal) [email protected] Andrew Webster Analyst in health negotiations, litigation, and administration (Ottawa) [email protected] Series editor & co-ordinator: Jill Torrie, Cree Public Health Department Cover design: Katya Petrov [email protected] Photo credit: Catherine Godin This document can be found online at: www.Creepublichealth.org Reproduction is authorised for non-commercial purposes with acknowledgement of the source. Document deposited on Santécom (http://www. Santecom.qc.ca) Call Number: INSPQ-2005-18-2005-001 Legal deposit – 2nd trimester 2005 Bibliothèque Nationale du Québec National Library of Canada ISSN: 2-550-443779-9 © April 2005. -

Fpcc-Newsletter-Spring-Summer-2014

first peoples’ news spring /summer 2014 first peoples’ cultural council IN THIS ISSUE New Museum Exhibition 2 New Arts Funding from FPCC Available for First Nations Youth SHOWCASING B.C.’S LIVING in B.C. FIRST NATIONS LANGUAGES 3 New Resources Available for First Nations Languages in B.C. Most people are unaware of the variety approaches with contemporary storytell- and richness of languages in this prov- ing. It will make use of audio and visual 4 FirstVoices Resources: Flash Card ince. With 34 Indigenous languages and media, artwork and narrative text in Eng- and Label Maker 61 dialects, B.C. is the most linguistically lish as well as First Nations languages. diverse region in Canada. Most importantly, it will demonstrate 4 Geek Alert! PC Keyboard In an inspiring new partnership, the the diversity and resilience of languages Software Update First Peoples’ Cultural Council (FPCC) in B.C. by showcasing languages by has been working with the Royal BC region as well as individual efforts to 5 Seabird Island Language Nests is Museum to create the innovative rejuvenate languages through hard work Engaging Young Language Learners Our Living Languages exhibition, which and perseverance. will provide an opportunity to celebrate “This is exciting for us and a progressive 6 Mentor-Apprentice Teams Creating these First Nations languages and the move on behalf of the Royal BC Museum,” a New Generation of Speakers people who are working to preserve says FPCC Chair Lorna Williams. “The and revitalize them. museum is a wonderful venue in which to 8 In Conversation with AADA Recipient The exhibition will fuse traditional share the stories and perspectives of First Kevin Loring Continued next page… 9 Upgrades to the FirstVoices Language Tutor Now Available to Communities 10 Community Success Story: SECWEPEMCTSÍN Language Tutor Lessons 11 FirstVoices Coordinator Peter Brand Retires…Or Does He? Our Living Languages: First Peoples' Voices in B.C. -

Past Tense, Imperfective Aspect, and Irreality in Cree

143 PAST TENSE, IMPERFECTIVE ASPECT, AND IRREALITY IN CREE Deborah James Scarborough College, University of Toronto In the Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi language complex, and also in at least some other Algonquian languages as well, there are two differ ent types of morphological device for indicating past tense. One of these is the use of a prefix, which in Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi takes the form /ki:/ or /ci:/.1 The other is the use of what are known in the literature as "preterit" suffixes. In the dialect of Moose Factory, Ontario, with which this paper will be primarily concerned, the pre terit suffix takes the form /htay/ when the verb is in the indepen dent indicative and when either the subject or the object of the verb is first or second person, and it take a form characterized basically by the element /pan/ in all other cases.2 It is of interest to ask how, if at all, these two devices for indicating past tense differ from each other in meaning and usage. In this paper, I will examine in detail one dialect, the Mosse Cree dialect, and I will show that there are two major types of difference between the /ki:/ prefix and the pre terit suffix. The first difference involves an aspectual distinction; the second involves the fact that the preterit—but not /ki:/—can be used to indicate things which are not past tense at all, but are instead hypothetical or irreal. And it will be shown that this latter use of the preterit is semantically linked both with its use to indicate past tense and also more specifically with its use to indicate aspect. -

Death and Life for Inuit and Innu

skin for skin Narrating Native Histories Series editors: K. Tsianina Lomawaima Alcida Rita Ramos Florencia E. Mallon Joanne Rappaport Editorial Advisory Board: Denise Y. Arnold Noenoe K. Silva Charles R. Hale David Wilkins Roberta Hill Juan de Dios Yapita Narrating Native Histories aims to foster a rethinking of the ethical, methodological, and conceptual frameworks within which we locate our work on Native histories and cultures. We seek to create a space for effective and ongoing conversations between North and South, Natives and non- Natives, academics and activists, throughout the Americas and the Pacific region. This series encourages analyses that contribute to an understanding of Native peoples’ relationships with nation- states, including histo- ries of expropriation and exclusion as well as projects for autonomy and sovereignty. We encourage collaborative work that recognizes Native intellectuals, cultural inter- preters, and alternative knowledge producers, as well as projects that question the relationship between orality and literacy. skin for skin DEATH AND LIFE FOR INUIT AND INNU GERALD M. SIDER Duke University Press Durham and London 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Arno Pro by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Sider, Gerald M. Skin for skin : death and life for Inuit and Innu / Gerald M. Sider. pages cm—(Narrating Native histories) Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5521- 2 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978- 0- 8223- 5536- 6 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Naskapi Indians—Newfoundland and Labrador—Labrador— Social conditions. -

Master of Arts

SOUI\D CHAI\IGE IN OtD MOI\ITAGITAIS by Christopher W. Haryey A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies ln Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS I)epartment of Linguistics Ilniversity of Manitoba \ffinnipeg, Manitoba @ Christopher'W. Harve¡ 2005 THE UNTVERSITY OF MANITOBA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES ?t*itJrrt COPYRIGHT PERMISSION SOUND CIIANGE IN OLD MONITAGNAIS BY Christopher W. Harvey A ThesislPracticum submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfillment of the requirement of the degree Master Of Arts Christopher W. Harvey O 2005 Permission has been granted to the Library of the University of Manitoba to lend or sell copies of this thesis/practicum, to the National Library of Canada to microfilm this thesis and to lend or sell copies of the film, and to University Microfilms Inc. to publish an abstract of this thesis/practicum. This reproduction or copy of this thesis has been made available by authority of the copyright owner solely for the purpose of private study and research, and may only be reproduced and copied as permitted by copyright laws or with express written authorization from the copyright owner. SOUND CHANGE IN OLD MONTAGNAIS Chris Harvey ABSTRACT This thesis looks at the sound changes which occurred from reconstructed Proto- Algonquian to Old Montagnais. The Old Montagnais language was recorded by the Jesuits during the seventeenth century in the region of Québec City, Lac Saint-Jean and the lower Saguenay River at the Tadoussac mission. Their most important works which survive to this day are two dictionaries, Díctionnaire montagnais by Antoine Silvy and Racines montagnøises by Bonaventure Fabvre. -

Evans, James Evans’ Brother, in 1927

THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO WESTERN ARCHIVES JAMES EVANS FONDS AFC 135 Inventory prepared by Alison Mitchell-Reid, based on student finding aid project(s) undertaken in partial fulfilment of archives course requirements – February 2010 2 WESTERN ARCHIVES AFC 135 JAMES EVANS FONDS TABLE OF CONTENTS FONDS DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................... 4 SERIES DESCRIPTIONS and FILE LISTS Series 1: Pamphlets and clippings about James Evans.............................................. 6 Series 2: Correspondence........................................................................................... 7 Sub-series 2.1: James Evans’ correspondence ................................................. 8 Sub-series 2.2: Letters concerning James Evans.............................................. 10 Series 3: Diaries and journals .................................................................................... 11 Sub-series 3.1: James Evans’ diaries................................................................ 12 Sub-series 3.2: Diary attributed to Thomas Hassall......................................... 13 Series 4: Poems and hymns ....................................................................................... 14 Series 5: Sermons, lectures and theological notes ..................................................... 15 Series 6: Cree language and syllabics documents ..................................................... 17 Series 7: Notes on North American aboriginal