The Faces of the Chariot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Generic Transformation of the Masoretic Text of Qohelet 9. 7-10 in the Targum Qohelet and Qohelet Midrash Rabbah

Durham E-Theses Wine, women and work: the generic transformation of the Masoretic text of Qohelet 9. 7-10 in the Targum Qohelet and Qohelet Midrash Rabbah Hardy, John Christopher How to cite: Hardy, John Christopher (1995) Wine, women and work: the generic transformation of the Masoretic text of Qohelet 9. 7-10 in the Targum Qohelet and Qohelet Midrash Rabbah, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5403/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 WINE, WOMEN AND WORK: THE GENERIC TRANSFORMATION OF THE MA50RETIC TEXT OF QOHELET 9. 7-10 IN THE TARGUM QOHELET AND QOHELET MIDRASH RABBAH John Christopher Hardy This tnesis seeks to understand the generic changes wrought oy targum Qonelet and Qoheiet raidrash rabbah upon our home-text, the masoretes' reading ot" woh. -

“Men of Faith” in 2 Enoch 35:2 and Sefer Hekhalot 48D:101

Andrei A. Orlov Marquette University The Heirs of the Enochic Lore: “Men of Faith” in 2 Enoch 35:2 and Sefer Hekhalot 48D:101 [forthcoming in Old Testament Apocrypha in the Slavonic Tradition: Continuity and Diversity. (Eds. L. DiTommaso and C. Böttrich; Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha Supplement Series; London/New York: T&T Clark, 2005)] “Make public the twenty-four books that you wrote first and let the worthy and the unworthy read them; but keep the seventy that were written last, in order to give them to the wise among your people. For in them is the spring of understanding, the fountain of wisdom, and the river of knowledge.” 4 Ezra 14 Enoch and Moses Chapter 35 of 2 (Slavonic) Enoch, a Jewish apocalypse apparently written in the first century CE,2 unveils the story of the transmission of the Enochic scriptures and their 1 Part of this paper was read at the Annual Meeting of SBL/AAR, San Antonio, 23-26 November 2004. 2 On the possible date of the pseudepigraphon see the following investigations: R. H. Charles and W. R. Morfill, The Book of the Secrets of Enoch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1896); M. I Sokolov, “Materialy i zametki po starinnoj slavjanskoj literature. Vypusk tretij, VII. Slavjanskaja Kniga Enoha Pravednogo. Teksty, latinskij perevod i izsledovanie. Posmertnyj trud avtora prigotovil k izdaniju M. Speranskij,“ COIDR 4 (1910), 165; N. Schmidt, "The Two Recensions of Slavonic Enoch," JAOS 41 (1921) 307-312; G. Scholem, Ursprung und Anfänge der Kabbala (SJ, 3; Berlin: De Gruyter, 1962), 62-64; M. -

Miriyam Goldman OA Thesis 9Dec20.Pdf (247.7Kb)

The Living Stone: The Talmudic Paradox of the Seventh Month Gestational Viability vs. the Eighth Month Non-Viability Presented to the S. Daniel Abraham Honors Program in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Completion of the Program Stern College for Women Yeshiva University December 9, 2020 Miriyam A. Goldman Mentor: Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss, Biology Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………………. 3 Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 4 Background to Pregnancy ……………………………………………………………………… 5 Talmudic Sources on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………. 6 Meforshim on the Dilemma ……………………………………………………………………. 9 Secular Sources of the Dilemma ………………………………………………………………. 11 The Significance of Hair and Nails in Terms of Viability……………………………….……... 14 The Definition of Nefel’s Impact on Viability ……………………………………………….. 17 History of Premature Survival ………………………………………………………………… 18 Statistics on Prematurity ………………………………………………………………………. 19 Developmental Differences Between Seventh and Eighth Months ……………………….…. 20 Contemporary Talmudic Balance of the Dilemma..…………………………………….…….. 22 Contemporary Secular Balance of the Dilemma .……………………………………….…….. 24 Evaluation of Talmudic Accreditation …………………………………………………..…...... 25 Interviews with Rabbi Eitan Mayer, Rabbi Daniel Stein, and Rabbi Dr. Richard Weiss .…...... 27 Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………….…. 29 References…..………………………………………………………………………………..… 34 2 Abstract This paper reviews the viability of premature infants, specifically the halachic status of those born in -

The Eschatological Role of the Seventh Antediluvian Hero in 2 (Slavonic) Enoch

ANDREI A. ORLOV THE PILLAR OF THE WORLD: THE ESCHATOLOGICAL ROLE OF THE SEVENTH ANTEDILUVIAN HERO IN 2 (SLAVONIC) ENOCH Introduction In chapter 25 of the 2 Enoch the Lord reveals to the translated antediluvian hero some unique details in the mysteries of creation found neither in earlier Enochic booklets nor in any other Second Temple Jewish materials. One of the important parts of this revelation deals with the order of events that preceded the visible creation. The Deity unveils to the seer that prior to visible creation he called out from nothing the luminous aeon Adoil ordering him to become the foundation of the upper things. The account describes the process of Adoil’s transmutation into the cornerstone of creation on which the Deity establishes his Throne. Several distinguished students of Jewish mystical traditions, including Gershom Scholem and Moshe Idel, noticed that this protological account in chapter 25 dealing with the establishment of the created order appears to parallel the order of eschatological events narrated in chapter 65 where during his short visit to earth Enoch conveys to his children the mystery of the last times. 1 According to Enoch’s instruction, after the final judgment time will collapse and all the righteous of the world will be incorporated into a single luminous aeon. The description of this final aeon appears to bear striking similarities with the primordial aeon Adoil portrayed in chapter 25 as the foundation of the created order. The text also seems to hint that the righteous Enoch, translated to heaven and transformed into a luminous celestial creature, is the first fruit of this eschatological aeon that will eventually gather all the righteous into a single entity. -

Mishnah: the New Scripture Territories in the East

176 FROM TEXT TO TRADITION in this period was virtually unfettered. The latter restriction seems to have been often compromised. Under the Severan dynasty (193-225 C.E.) Jewish fortunes improved with the granting of a variety of legal privileges culminating in full Roman citizenship for Jews. The enjoyment of these privileges and the peace which Jewry enjoyed in the Roman Empire were·· interrupted only by the invasions by the barbarians in the West 10 and the instability and economic decline they caused throughout the empire, and by the Parthian incursions against Roman Mishnah: The New Scripture territories in the East. The latter years of Roman rule, in the aftermath of the Bar Kokhba Revolt and on the verge of the Christianization of the empire, were extremely fertile ones for the development of . The period beginning with the destruction (or rather, with the Judaism. It was in this period that tannaitic Judaism came to its restoration in approximately 80 C.E.) saw a fundamental change final stages, and that the work of gathering its intellectual in Jewish study and learning. This was the era in which the heritage, the Mishnah, into a redacted collection began. All the Mishnah was being compiled and in which many other tannaitic suffering and the fervent yearnings for redemption had culmi traditions were taking shape. The fundamental change was that nated not in a messianic state, but in a collection of traditions the oral Torah gradually evolved into a fixed corpus of its own which set forth the dreams and aspirations for the perfect which eventually replaced the written Torah as the main object holiness that state was to engender. -

The Greatest Mirror: Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha

The Greatest Mirror Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha Andrei A. Orlov On the cover: The Baleful Head, by Edward Burne-Jones. Oil on canvas, dated 1886– 1887. Courtesy of Art Resource. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2017 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production, Dana Foote Marketing, Fran Keneston Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Orlov, Andrei A., 1960– author. Title: The greatest mirror : heavenly counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha / Andrei A. Orlov. Description: Albany, New York : State University of New York Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016052228 (print) | LCCN 2016053193 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438466910 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438466927 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Apocryphal books (Old Testament)—Criticism, interpretation, etc. Classification: LCC BS1700 .O775 2017 (print) | LCC BS1700 (ebook) | DDC 229/.9106—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016052228 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For April DeConick . in the season when my body was completed in its maturity, there imme- diately flew down and appeared before me that most beautiful and greatest mirror-image of myself. -

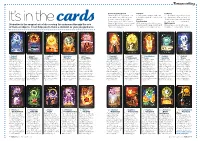

Fortune Telling

Fortune telling How to use the spread Intuition Dowsing Relax and focus on the question Slowly open your eyes and then Using a pendulum, ask it to show you want to ask - this can be as select the card that you feel most you a movement for ‘yes’ and ‘no’. general or specific as you like. drawn to. Then hover it over each card until It’s in the Then, using one of the following Psychometry you get a ‘yes’ - this is your card. forms of divination, choose a card With your eyes closed, run your Bibliomancy Divination is the magical art of discoveringcards the unknown through the use and read the summary you have hand across the page and stop at Close your eyes and with your of tools or objects. It can help you to make a decision or give you guidance chosen for guidance. the card you feel is right for you. finger point to any card at random. Gabriel Hanael Jophiel Metatron Uriel Zaphkiel Jophiel Sandalphon Zadkiel Gabriel 1 Balance 2Willpower 3 Joy 4 Miracles 5 Friendship 6 Surrender 7 Forgiveness 8 Love 9 Security 10 Grace Gabriel wants you to The great whales of The card you have Miracles are changes Uriel wishes you to The angels want you to Jophiel asks you to let This angelic oracle The angels unite The oracle of Gabriel know that you have the oceans deep are chosen brings forth a of perception and know that the true know that you are go of the pain of the comes to you as with their powerful wishes you to receive been too busy. -

The Nonverbal Language of Prayer

Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism Texte und Studien zum Antiken Judentum Edited by Martin Hengel and Peter Schäfer 105 Uri Ehrlich The Nonverbal Language of Prayer A New Approach to Jewish Liturgy Translated by Dena Ordan Mohr Siebeck Uri Ehrlich: Born 1956; 1994 Ph.D. in Talmud and Jewish Philosophy, Hebrew University, Jerusalem; Senior lecturer, Department of Jewish Thought, Ben-Gurion University. ISBN 3-16-148150-X ISSN 0721-8753 (Texts and Studies in Ancient Judaism) Die Deutsche Bibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; de- tailed bibliographic data is available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de. © 2004 by Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen, Germany. Authorised English translation of "n:-ßxn 'ra^a © 1999 by Hebrew University Magnes Press, Jerusalem. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that permitted by copyright law) without the publisher's written permission. This applies particularly to reproductions, translations, microfilms and storage and processing in electronic systems. The book was printed by Guide-Druck in Tübingen on non-aging paper and bound by Buchbinderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. In memory of my grandparents Martha and Arthur Dernburg Preface to the English Edition Prayer has many names: tefillah (petition), tehinah (beseeching), le'akah (shouting), ze'akah (cry), shavah (cry for help), renanah (cry of prayer), pegi'ah (plea), nefilah (falling down); amidah (standing). (Tanhuma, Va-ethanan 3) This midrash highlights the multidimensional nature of the Prayer and names a variety of expressive means alongside the Prayer's verbal aspect. It is this book's aim to portray the nonverbal components of the Prayer - physical gestures, attire, and vocality - and to demonstrate their impor- tance for, and integrality to, the prayer-act. -

The Name of God the Golem Legend and the Demiurgic Role of the Alphabet 243

CHAPTER FIVE The Name of God The Golem Legend and the Demiurgic Role of the Alphabet Since Samaritanism must be viewed within the wider phenomenon of the Jewish religion, it will be pertinent to present material from Judaism proper which is corroborative to the thesis of the present work. In this Chapter, the idea about the agency of the Name of God in the creation process will be expounded; then, in the next Chapter, the various traditions about the Angel of the Lord which are relevant to this topic will be set forth. An apt introduction to the Jewish teaching about the Divine Name as the instrument of the creation is the so-called golem legend. It is not too well known that the greatest feat to which the Jewish magician aspired actually was that of duplicating God's making of man, the crown of the creation. In the Middle Ages, Jewish esotericism developed a great cycle of golem legends, according to which the able magician was believed to be successful in creating a o ?� (o?u)1. But the word as well as the concept is far older. Rabbinic sources call Adam agolem before he is given the soul: In the first hour [of the sixth day], his dust was gathered; in the second, it was kneaded into a golem; in the third, his limbs were shaped; in the fourth, a soul was irifused into him; in the fifth, he arose and stood on his feet[ ...]. (Sanh. 38b) In 1615, Zalman �evi of Aufenhausen published his reply (Jii.discher Theriak) to the animadversions of the apostate Samuel Friedrich Brenz (in his book Schlangenbalg) against the Jews. -

Eschatology and the Book of Revelation

David M. Williams Eschatology and The Book of Revelation Contents CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................................... 1 ESCHATOLOGY AND THE BOOK OF REVELATION ....................................................................... 3 THE FOUR UNDERSTANDINGS OF THE BOOK OF REVELATION........................................................................ 3 Introduction.............................................................................................................................................. 3 Idealist ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Preterist.................................................................................................................................................... 3 Historicist................................................................................................................................................. 5 Futurist..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Conclusion ............................................................................................................................................... 7 THE CHRISTOLOGY OF REVELATION............................................................................................................. 8 Introduction............................................................................................................................................. -

Translating a Midrash-Compilation Some New Considerations

TRANSLATING A MIDRASH-COMPILATION SOME NEW CONSIDERATIONS by JACOB NEUSNER Brown University The purpose of this paper is to adumbrate a few points of interest in the study of a biblical book. The book at hand is Leviticus. What I want to know is how systematically to analyze the composition of the rabbinical exegeses of passages of that book assembled in the collection known as Leviticus Rabbah. With Leviticus Rabbah we enjoy the results of a truly great scholarly achievement. Mordecai Margulies Midrash Wayyikra Rabbah. A Critical Edition Based on Manuscripts and Genizah Fragments with Variants and Notes (Jerusalem. 1953-1960. 1-V). Margulies placed the study of Leviticus Rabbah on an entirely new foundation. How so? He supplied an authori tative account of the two basic issues of any ancien~ document: the text and the principal philological problems. At the same time he left open cer tain analytical questions. One of these may be called redactional. This is in two aspects. First. we want to know how to distinguish the distinct components of the composition. The text clearly is composite. Then what are the individ ual units out of which the composition was constructed? A glance at the excellent translation by J. lsraelstam and Judah J. Slotki. Midrash Rab bah ... Leviticus (London. 1939) shows that differentiation among units of thought stands at a rather primitive stage. lsraelstam and Slotki present us with long paragraphs, not indicating that these paragraphs are made up of numerous individual units of thought. They also do not sys tematically tell us which units of thought are shared among other docu ments, and which ones represent the contribution of the framers of the text at hand alone. -

A Whiteheadian Interpretation of the Zoharic Creation Story

A WHITEHEADIAN INTERPRETATION OF THE ZOHARIC CREATION STORY by Michael Gold A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Michael Gold ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to express sincere gratitude to his committee members, Professors Marina Banchetti, Frederick E. Greenspahn, Kristen Lindbeck, and Eitan Fishbane for their encouragement and support throughout this project. iv ABSTRACT Author: Michael Gold Title: A Whiteheadian Interpretation of the Zoharic Creation Story Institution: Florida Atlantic University Dissertation Advisor: Dr. Marina P. Banchetti Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Year: 2016 This dissertation presents a Whiteheadian interpretation of the notions of mind, immanence and process as they are addressed in the Zohar. According to many scholars, this kabbalistic creation story as portrayed in the Zohar is a reaction to the earlier rabbinic concept of God qua creator, which emphasized divine transcendence over divine immanence. The medieval Jewish philosophers, particularly Maimonides influenced by Aristotle, placed particular emphasis on divine transcendence, seeing a radical separation between Creator and creation. With this in mind, these scholars claim that one of the goals of the Zohar’s creation story was to emphasize God’s immanence within creation. Similar to the Zohar, the process metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead and his followers was reacting to the substance metaphysics that had dominated Western philosophy as far back as ancient Greek thought. Whitehead adopts a very similar narrative to that of the Zohar.