Miriyam Goldman OA Thesis 9Dec20.Pdf (247.7Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

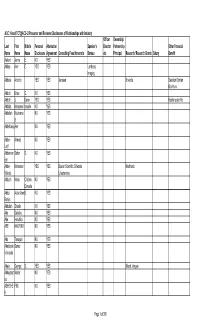

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

Kol HAMESHAKKER

r'"- ----- -- - .;...__ ·---· - ~ - KoL HAMESHAKKER - *!EJ #' _PC$$8#'' The Jewish Thought Propaganders of T80'J PK/ CB" laPblcb Editors-in-Chief the Yeshiva University student Body 0 1 cd'=l/Gdeeb ! II #$ t&'{) *+'*, - *. I01Z3*4#5 1 ! II I +I (! **4 #0578go/o#Q2'78go/~ Associate Editors Sem Girl Says: A Testament To the (;I<</ Z =0:#5! I 4r:/ + Depth of Human Insight......... ... .... .4 Editors' Thoughts: The >I <0:#5#(? 11 lf@A 11 B- I. %l- :5110 Hannah Dreyfus Great Bright Future BY: Mr. Social-Conservative Jewish Intellectual Thinker Copy Editor From the Censorship Committee: The 7 :fK1IfJ cE :51!12') 81 m This has been year of profound soul-searching for Kol Case for Banning #BZ#q - *~\\\d a Kj $$#0/d J Hameshakker. As Jewish Thought delegates for the student Re'uven Ben-Shimon, Committee . Design Editor body of the bestideology' s Flagship Institution, we editors Chair keeP. an ear toward the feelings of the community and the >IOO.#S(F I ++I <If- :4$B't02'EO*. unique needs of Modern Orthodoxy. In so doing, it has become increasingly clear to us that we need to consider Staff Writers Cast Aside: Confronting- I 1/ ry B=+/ $" :J in the future, and dictate it. Some convoluted explanation is > :r;J 11 (@1 @I 0/d ZEI rt911 the Modern Orthodox Community............ 7 now in order. G 9* <' (E #I Cl2' E#Ot$B'F:+ Rally Capman Although our community's Torah U-Madda value system emphasizes the attention to modernity that so many other -I ++I II I (1-0#$11 gogr 0#&,8$ </ Jews unfortunately lack, we have a failure of our own in =11 J (ha-ShalemZt-0:#1J I++ CJF: Bringing Z:<<8J to Life .................. -

Sanhedrin 053.Pub

ט"ז אלול תשעז“ Thursday, Sep 7 2017 ן נ“ג סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT to apply stoning to other cases גזירה שוה Strangulation for adultery (cont.) The source of the (1 ואלא מכה אביו ואמו קא קשיא ליה, למיתי ולמיגמר מאוב וידעוני R’ Yoshiya’s opinion in the Beraisa is unsuccessfully וכו ‘ ליגמרו מאשת איש, דאי אתה רשאי למושכה להחמיר עליה וכו‘ .challenged at the bottom of 53b lists אלו הן הנסקלין Stoning T he Mishnah of (2 The Mishnah later derives other cases of stoning from a many cases which are punished with stoning. R’ Zeira notes gezeirah shavah from Ov and Yidoni. R’ Zeira questions that the Torah only specifies stoning explicitly in a handful גזירה שוה of cases, while the other cases are learned using a דמיהם בם or the words מות יומתו whether it is the words Rashi states that the cases where we find . אוב וידעוני that are used to make that gezeirah shavah. from -stoning explicitly are idolatry, adultery of a betrothed maid . דמיהם בם Abaye answers that it is from the words Abaye’s explanation is defended. en, violating the Shabbos, sorcery and cursing the name of R’ Acha of Difti questions what would have bothered R’ God. Aruch LaNer points out that there are three addition- Zeira had the gezeirah shavah been made from the words al cases where we find stoning mentioned outright (i.e., sub- ,mitting one’s children to Molech, inciting others to idolatry . מות יומתו In any case, there .( בן סורר ומורה—After R’ Acha of Difti suggests and rejects a number of and an recalcitrant son גזירה possible explanations Ravina explains what was troubling R’ are several cases of stoning which are derived from the R’ Zeira asks Abaye to identify the source from which . -

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon Ha-Ra and Motzi Shem Ra and Disclosing Another’S Confidential Secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon ha-ra and motzi shem ra and disclosing another’s confidential secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech Deut. 24:9 - "Remember what the L-rd your G-d did unto Miriam by the way as you came forth out of Egypt." Specifically, she spoke against her brother Moses. Yerushalmi Berachos 1:2 Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai said, “Had I been at Mount Sinai at the moment when the torah was given to Yisrael I would have demanded that man should have been created with two mouths- one for Torah and prayer and other for mundane matters. But then I retracted and exclaimed that if we fail and speak lashon hara with only one mouth, how much more so would we fail with two mouths Bavli Arakhin15b R. Yochanan said in the name of R.Yosi ben Zimra: He who speaks slander, is as though he denied the existence of the Lord: With out tongue will we prevail our lips are our own; who is lord over us? (Ps.12:5) Gen R. 65:1 and Lev.R. 13:5 The company of those who speak slander cannot greet the Presence Sotah 5a R. Hisda said in the name of Mar Ukba: When a man speaks slander, the holy one says, “I and he cannot live together in the world.” So scripture: “He who slanders his neighbor in secret…. Him I cannot endure” (Ps. 101:5).Read not OTO “him’ but ITTO “with him [I cannot live] Deut.Rabbah 5:10 R.Mana said: He who speaks slander causes the Presence to depart from the earth below to heaven above: you may see foryourselfthat this is so.Consider what David said: “My soul is among lions; I do lie down among them that are aflame; even the sons of men, whose teeth are spears and arrows, and their tongue a sharp sword” (Ps.57:5).What follows directly ? Be Thou exalted O God above the heavens (Ps.57:6) .For David said: Master of the Universe what can the presence do on the earth below? Remove the Presence from the firmament. -

The Greatest Mirror: Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha

The Greatest Mirror Heavenly Counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha Andrei A. Orlov On the cover: The Baleful Head, by Edward Burne-Jones. Oil on canvas, dated 1886– 1887. Courtesy of Art Resource. Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2017 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY www.sunypress.edu Production, Dana Foote Marketing, Fran Keneston Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Orlov, Andrei A., 1960– author. Title: The greatest mirror : heavenly counterparts in the Jewish Pseudepigrapha / Andrei A. Orlov. Description: Albany, New York : State University of New York Press, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016052228 (print) | LCCN 2016053193 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438466910 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438466927 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Apocryphal books (Old Testament)—Criticism, interpretation, etc. Classification: LCC BS1700 .O775 2017 (print) | LCC BS1700 (ebook) | DDC 229/.9106—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016052228 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 For April DeConick . in the season when my body was completed in its maturity, there imme- diately flew down and appeared before me that most beautiful and greatest mirror-image of myself. -

Levirate in Ancient Israel: Overlapping Frames with Early Indian Practice of Niyoga

Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal – Vol.5, No.7 Publication Date: July. 25, 2018 DoI:10.14738/assrj.57.4880. Sahgal, S. (2018). Levirate in Ancient Israel: Overlapping Frames with Early Indian Practice of Niyoga. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 5(7) 240-248. Levirate in Ancient Israel: Overlapping Frames with Early Indian Practice of Niyoga Dr. Smita Sahgal Associate Professor, Department of History, Lady Shri Ram College, (University of Delhi) Lajpat Nagar, New Delhi-110024 ABSTRACT Surrogacy was a well-known practice in ancient societies. Its application was rare but mandated when the matter of threatened lineage surfaced. Since very early times and particularly within patriarchal societies, sons were regarded as natural inheritors of property, holders of lineage and on many occasions performers of rites for ancestors. Hence, the absence of a male issue was viewed as a solemn social anomaly. Corrective solutions had to be worked out and many ancient societies came up with their alternative paradigms. In ancient Israel the practice of yibbum emerged and ensured lineage continuity. Its ancient Indian counterpart was the practice of niyoga that came under what is largely understood as apaddharma or the law of exigency. In both societies childless widow/wife was made to cohabit with a man, generally from within the family and the son produced furthered the lineage of her husband. The consent of the widow/wife was not really sought for the practice to get its social sanction. In the paper we shall study the issue from a gendered perspective and explore whether the practices of Yibbum and Niyoga implied exploitation of women. -

Shavuot 5780 Divrei Torah

Shavuot 5780 Divrei Torah Sponsored by: Debbie and Orin Golubtchik in honor of: The yahrzeits of Orin's parents חביבה בת שמואל משה בן חיים ליב Barbara and Simcha Hochman & family in memory of: • Simcha’s father, Rabbi Jonas Hochman a"h and • Gedalya ben Avraham, Blima bat Yaakov, Eeta bat Noach and Chaya bat Gedalya, who were murdered upon arrival at Birkenau on the 2nd day Shavuot. Table of Contents Page 3 Forward by Rabbi Adler ”That which you can and cannot do on Yom Tov אכל נפש“ Page 5 Yaakov Blau “Shifting voices in the narrative of Tanach” Page 9 Leeber Cohen “The Importance of Teaching Torah to Grandchildren” Page 11 Elchanan Dulitz “Bezchus Rabbi Dr. Baruch Tzvi ben R. Reuven Nassan z”l Mai Chanukah” Page 15 Martin Fineberg “Shavuos 5780 D’var Torah” Page 19 Yehuda Halpert “Ruth and Orpah’s Wedding Album: Fake News or Biblical Commentary” Page 23 Terry Novetsky “The “Mitzva” of Shavuot” Page 31 Yitzchak Shulman “Parshat Behaalotcha “ Page 33 Bernard Stahl The Meaning of Humility Page 41 Murray Sragow “Jews and Booze—A look at Jewish responses to Prohibition” Page 49 Mark Teicher “Intertextuality/Numerology” Page 50 Mark Zitter ”קרבנות של חג השבועות“ 2 Forward by Rabbi Adler Chaveireinu HaYikarim, Every year on the first night of Shavuot many of us get together for the purpose of learning with one another. There are multiple shiurim and many hours of chavruta learning . Unfortunately, in today’s climate we cannot learn with one another but we can learn from one another. Enclosed are a variety of Torah articles on many different topics which you are invited to enjoy during the course of Zman Matan Torahteinu. -

Tanya Sources.Pdf

The Way to the Tree of Life Jewish practice entails fulfilling many laws. Our diet is limited, our days to work are defined, and every aspect of life has governing directives. Is observance of all the laws easy? Is a perfectly righteous life close to our heart and near to our limbs? A righteous life seems to be an impossible goal! However, in the Torah, our great teacher Moshe, Moses, declared that perfect fulfillment of all religious law is very near and easy for each of us. Every word of the Torah rings true in every generation. Lesson one explores how the Tanya resolved these questions. It will shine a light on the infinite strength that is latent in each Jewish soul. When that unending holy desire emerges, observance becomes easy. Lesson One: The Infinite Strength of the Jewish Soul The title page of the Tanya states: A Collection of Teachings ספר PART ONE לקוטי אמרים חלק ראשון Titled הנקרא בשם The Book of the Beinonim ספר של בינונים Compiled from sacred books and Heavenly מלוקט מפי ספרים ומפי סופרים קדושי עליון נ״ע teachers, whose souls are in paradise; based מיוסד על פסוק כי קרוב אליך הדבר מאד בפיך ובלבבך לעשותו upon the verse, “For this matter is very near to לבאר היטב איך הוא קרוב מאד בדרך ארוכה וקצרה ”;you, it is in your mouth and heart to fulfill it בעזה״י and explaining clearly how, in both a long and short way, it is exceedingly near, with the aid of the Holy One, blessed be He. "1 of "393 The Way to the Tree of Life From the outset of his work therefore Rav Shneur Zalman made plain that the Tanya is a guide for those he called “beinonim.” Beinonim, derived from the Hebrew bein, which means “between,” are individuals who are in the middle, neither paragons of virtue, tzadikim, nor sinners, rishoim. -

The Name of God the Golem Legend and the Demiurgic Role of the Alphabet 243

CHAPTER FIVE The Name of God The Golem Legend and the Demiurgic Role of the Alphabet Since Samaritanism must be viewed within the wider phenomenon of the Jewish religion, it will be pertinent to present material from Judaism proper which is corroborative to the thesis of the present work. In this Chapter, the idea about the agency of the Name of God in the creation process will be expounded; then, in the next Chapter, the various traditions about the Angel of the Lord which are relevant to this topic will be set forth. An apt introduction to the Jewish teaching about the Divine Name as the instrument of the creation is the so-called golem legend. It is not too well known that the greatest feat to which the Jewish magician aspired actually was that of duplicating God's making of man, the crown of the creation. In the Middle Ages, Jewish esotericism developed a great cycle of golem legends, according to which the able magician was believed to be successful in creating a o ?� (o?u)1. But the word as well as the concept is far older. Rabbinic sources call Adam agolem before he is given the soul: In the first hour [of the sixth day], his dust was gathered; in the second, it was kneaded into a golem; in the third, his limbs were shaped; in the fourth, a soul was irifused into him; in the fifth, he arose and stood on his feet[ ...]. (Sanh. 38b) In 1615, Zalman �evi of Aufenhausen published his reply (Jii.discher Theriak) to the animadversions of the apostate Samuel Friedrich Brenz (in his book Schlangenbalg) against the Jews. -

Translating a Midrash-Compilation Some New Considerations

TRANSLATING A MIDRASH-COMPILATION SOME NEW CONSIDERATIONS by JACOB NEUSNER Brown University The purpose of this paper is to adumbrate a few points of interest in the study of a biblical book. The book at hand is Leviticus. What I want to know is how systematically to analyze the composition of the rabbinical exegeses of passages of that book assembled in the collection known as Leviticus Rabbah. With Leviticus Rabbah we enjoy the results of a truly great scholarly achievement. Mordecai Margulies Midrash Wayyikra Rabbah. A Critical Edition Based on Manuscripts and Genizah Fragments with Variants and Notes (Jerusalem. 1953-1960. 1-V). Margulies placed the study of Leviticus Rabbah on an entirely new foundation. How so? He supplied an authori tative account of the two basic issues of any ancien~ document: the text and the principal philological problems. At the same time he left open cer tain analytical questions. One of these may be called redactional. This is in two aspects. First. we want to know how to distinguish the distinct components of the composition. The text clearly is composite. Then what are the individ ual units out of which the composition was constructed? A glance at the excellent translation by J. lsraelstam and Judah J. Slotki. Midrash Rab bah ... Leviticus (London. 1939) shows that differentiation among units of thought stands at a rather primitive stage. lsraelstam and Slotki present us with long paragraphs, not indicating that these paragraphs are made up of numerous individual units of thought. They also do not sys tematically tell us which units of thought are shared among other docu ments, and which ones represent the contribution of the framers of the text at hand alone. -

The Temple and Toilet Practices in Rabbinic Palestine and Babylonia

Journal for the Study of Judaism Journal for the Study of Judaism 43 (2012) 328-368 brill.nl/jsj ‘Their Backs toward the Temple, and Their Faces toward the East:’ The Temple and Toilet Practices in Rabbinic Palestine and Babylonia Rachel Neis University of Michigan [email protected] Abstract This article treats the cultural meaning of rabbinic toilet rules from their Tannaitic instantiation through to later developments in Palestine and Mesopotamia. It argues that these rules draw their corporeal and mental bearings from the Jerusa- lem temple, in inverse and opposite directions to prayer deportment. It shows how the juxtaposition of the sacred (temple) and profane (toilet) triggered the temple in unlikely instances under the guise of prohibition. As such, toilet rules are the underside of a rabbinic mapping project, similar to rules of bodily orienta- tion in prayer. This map, effectively drawn by corporeal direction and orientation, with the (absent) temple at its center, traversed Palestine and the Diaspora, and ignored contemporary religious and imperials maps and limes. Thus developing toilet practices can tell us something about how a minority religious and social formation shaped bodily functions not necessarily in the more predictable terms of disgust and expulsion but rather as devices through which to uphold a lost center. Keywords rabbis, temple, toilet, Jerusalem, sacred, body, prayer My God, you go to the toilet and you sit on ideology!1 A worker at the Religious Council in Lod decorated a wall with pictures of rabbis without realizing that he would stop the disgusting habit of urinating 1) See the lecture presented by Slavoj Žižek, www.youtube.com/watch?v=FJ73hLQ64Ng at 3 minutes and 29 seconds.