Shavuot 5780 Divrei Torah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Path to Follow a Hevrat Pinto Publication Pikudei 381

The Path To Follow A Hevrat Pinto Publication Pikudei 381 Under the Direction of Rabbi David H. Pinto Shlita Adar I 29th 5771 www.hevratpinto.org | [email protected] th Editor-in-Chief: Hanania Soussan March 5 2011 32 rue du Plateau 75019 Paris, France • Tel: +331 48 03 53 89 • Fax: +331 42 06 00 33 Rabbi David Pinto Shlita Batei Midrashim As A Refuge Against The Evil Inclination is written, “These are the accounts of the Sanctuary, the Sanctuary of Moreover, what a person studies will only stay with him if he studies in a Beit Testimony” (Shemot 38:21). Our Sages explain that the Sanctuary was HaMidrash, as it is written: “A covenant has been sealed concerning what we a testimony for Israel that Hashem had forgiven them for the sin of the learn in the Beit HaMidrash, such that it will not be quickly forgotten” (Yerushalmi, golden calf. Moreover, the Midrash (Tanchuma, Pekudei 2) explains Berachot 5:1). I have often seen men enter a place of study without the intention that until the sin of the golden calf, G-d dwelled among the Children of of learning, but simply to look at what was happening there. Yet they eventually ItIsrael. After the sin, however, His anger prevented Him from dwelling among them. take a book in hand and sit down among the students. This can only be due to the The nations would then say that He was no longer returning to His people, and sound of the Torah and its power, a sound that emerges from Batei Midrashim and therefore to show the nations that this would not be the case, He told the Children conquers their evil inclination, lighting a spark in the heart of man so he begins to of Israel: “Let them make Me a Sanctuary, that I may dwell among them” (Shemot study. -

ACC14 and Tctacci2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures B.Pdf

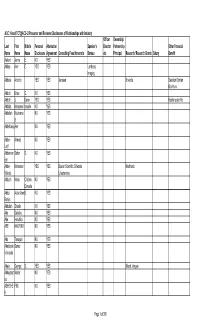

ACC.14 and TCT@ACC-i2 Presenter and Reviewer Disclosures of Relationships with Industry Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Aaland Jenna E. NO YES Abbas Amr E. YES YES Lantheus Imaging Abbate Antonio YES YES Janssen Novartis Swedish Orphan Biovitrum Abbott Brian G. NO YES Abbott J. Dawn YES YES Boston scientific Abdalla Mohamed Ismaile NO YES Abdallah Mouhama NO YES d Abdelbaky Amr NO YES Abdel- Ahmed NO YES Latif Abdelmon Sahar S. NO YES eim Abdel- Mohamed YES YES Boston Scientific, Edwards Medtronic Wahab Lifesciences Abduch Maria Cristina NO YES Donadio Abdul Aizai Azan B. NO YES Rahim Abdullah Shuaib NO YES Abe Daisuke NO YES Abe Haruhiko NO YES ABE NAOYUKI NO YES Abe Takayuki NO YES Abedzade Sanaz NO YES h Anaraki Abela George S. YES YES Merck, Amgen Abhayarat Walter NO YES na ABHISHE FNU NO YES K Page 1 of 350 Officer Ownership Last First Middle Personal Attestation Speaker's Director Partnership Other Financial Name Name Name Disclosure Agreement Consulting Fees Honoraria Bureau etc Principal Research/ Research Grants Salary Benefit Abidi Syed NO YES Abidov Aiden NO YES Abi-samra Freddy Michel NO YES Abizaid Alexandre YES YES Abbott, Boston Scientific Abo- Elsayed NO YES Salem Abou- Alex NO YES Chebl AbouEzze Omar F NO YES ddine Aboulhosn Jamil A. YES YES GE Medical, Actelion United Therapeutics, Actelion Pharmaceuticals Pharmaceuticals Abraham Jacob NO YES Abraham JoEllyn Moore NO YES Abraham Maria Roselle NO YES Abraham Theodore P. -

400 Editor RABBI SHIMON HELINGER

ב"ה למען ישמעו • פרשת תצוה • 400 EDITOR RABBI SHIMON HELINGER PURIM A POTENT DAY INTENSE REJOICING The Rebbe once said: It’s obvious that we must distance ourselves entirely The Zohar notes that Purim is similar to Yom We read in the Gemara that on Purim one must drink from anything negative (“cursed be Haman”), HaKipurim. This means that what is accomplished “until he cannot differentiate (“ad d’lo yada”) between and seek to treasure and embrace all good things on Yom Kippur by fasting can be accomplished ‘cursed be Haman’ and ‘blessed be Mordechai.’ ” (“blessed be Mordechai”). That applies at any time. on Purim by rejoicing. Furthermore, the very The Gemara relates a story of two amoraim, Rabbah The unique aspect of Purim is that we can accomplish name Kipurim (“like Purim”), implies that Purim and Rav Zeira, who had their Purim seuda together, this by allowing our neshama to express itself freely. is the greater Yom-Tov, impacting a person sharing profound secrets of the Torah over a This kind of avoda is superior to serving HaShem by more powerfully. number of cups of wine. However, Rav Zeira was so means of conscious thought (yada). Indeed, in this Indeed, Chazal teach that when Moshiach comes, all overwhelmed by the intense kedusha of Rabbah’s kind of avoda we can resemble the Yidden at the the Yomim-Tovim will cease to exist; only the Yom- revelations that his neshama left his body. time of the Purim story who, when the inner power Tov of Purim will remain. Chassidus explains that of their neshamos surfaced, fulfilled all the mitzvos the joy and holiness of Purim are so great, that even faithfully, even to the point of mesiras nefesh. -

Sanhedrin 053.Pub

ט"ז אלול תשעז“ Thursday, Sep 7 2017 ן נ“ג סנהדרי OVERVIEW of the Daf Distinctive INSIGHT to apply stoning to other cases גזירה שוה Strangulation for adultery (cont.) The source of the (1 ואלא מכה אביו ואמו קא קשיא ליה, למיתי ולמיגמר מאוב וידעוני R’ Yoshiya’s opinion in the Beraisa is unsuccessfully וכו ‘ ליגמרו מאשת איש, דאי אתה רשאי למושכה להחמיר עליה וכו‘ .challenged at the bottom of 53b lists אלו הן הנסקלין Stoning T he Mishnah of (2 The Mishnah later derives other cases of stoning from a many cases which are punished with stoning. R’ Zeira notes gezeirah shavah from Ov and Yidoni. R’ Zeira questions that the Torah only specifies stoning explicitly in a handful גזירה שוה of cases, while the other cases are learned using a דמיהם בם or the words מות יומתו whether it is the words Rashi states that the cases where we find . אוב וידעוני that are used to make that gezeirah shavah. from -stoning explicitly are idolatry, adultery of a betrothed maid . דמיהם בם Abaye answers that it is from the words Abaye’s explanation is defended. en, violating the Shabbos, sorcery and cursing the name of R’ Acha of Difti questions what would have bothered R’ God. Aruch LaNer points out that there are three addition- Zeira had the gezeirah shavah been made from the words al cases where we find stoning mentioned outright (i.e., sub- ,mitting one’s children to Molech, inciting others to idolatry . מות יומתו In any case, there .( בן סורר ומורה—After R’ Acha of Difti suggests and rejects a number of and an recalcitrant son גזירה possible explanations Ravina explains what was troubling R’ are several cases of stoning which are derived from the R’ Zeira asks Abaye to identify the source from which . -

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon Ha-Ra and Motzi Shem Ra and Disclosing Another’S Confidential Secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech

Source Sheet on Prohibitions on Loshon ha-ra and motzi shem ra and disclosing another’s confidential secrets and Proper Etiquette for Speech Deut. 24:9 - "Remember what the L-rd your G-d did unto Miriam by the way as you came forth out of Egypt." Specifically, she spoke against her brother Moses. Yerushalmi Berachos 1:2 Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai said, “Had I been at Mount Sinai at the moment when the torah was given to Yisrael I would have demanded that man should have been created with two mouths- one for Torah and prayer and other for mundane matters. But then I retracted and exclaimed that if we fail and speak lashon hara with only one mouth, how much more so would we fail with two mouths Bavli Arakhin15b R. Yochanan said in the name of R.Yosi ben Zimra: He who speaks slander, is as though he denied the existence of the Lord: With out tongue will we prevail our lips are our own; who is lord over us? (Ps.12:5) Gen R. 65:1 and Lev.R. 13:5 The company of those who speak slander cannot greet the Presence Sotah 5a R. Hisda said in the name of Mar Ukba: When a man speaks slander, the holy one says, “I and he cannot live together in the world.” So scripture: “He who slanders his neighbor in secret…. Him I cannot endure” (Ps. 101:5).Read not OTO “him’ but ITTO “with him [I cannot live] Deut.Rabbah 5:10 R.Mana said: He who speaks slander causes the Presence to depart from the earth below to heaven above: you may see foryourselfthat this is so.Consider what David said: “My soul is among lions; I do lie down among them that are aflame; even the sons of men, whose teeth are spears and arrows, and their tongue a sharp sword” (Ps.57:5).What follows directly ? Be Thou exalted O God above the heavens (Ps.57:6) .For David said: Master of the Universe what can the presence do on the earth below? Remove the Presence from the firmament. -

Jiddistik Heute

לקט ייִ דישע שטודיעס הנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today לקט Der vorliegende Sammelband eröffnet eine neue Reihe wissenschaftli- cher Studien zur Jiddistik sowie philolo- gischer Editionen und Studienausgaben jiddischer Literatur. Jiddisch, Englisch und Deutsch stehen als Publikationsspra- chen gleichberechtigt nebeneinander. Leket erscheint anlässlich des xv. Sym posiums für Jiddische Studien in Deutschland, ein im Jahre 1998 von Erika Timm und Marion Aptroot als für das in Deutschland noch junge Fach Jiddistik und dessen interdisziplinären אָ רשונג אויסגאַבעס און ייִדיש אויסגאַבעס און אָ רשונג Umfeld ins Leben gerufenes Forum. Die im Band versammelten 32 Essays zur jiddischen Literatur-, Sprach- und Kul- turwissenschaft von Autoren aus Europa, den usa, Kanada und Israel vermitteln ein Bild von der Lebendigkeit und Viel- falt jiddistischer Forschung heute. Yiddish & Research Editions ISBN 978-3-943460-09-4 Jiddistik Jiddistik & Forschung Edition 9 783943 460094 ִיידיש ַאויסגאבעס און ָ ארשונג Jiddistik Edition & Forschung Yiddish Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 לקט ִיידישע שטודיעס ַהנט Jiddistik heute Yiddish Studies Today Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Yidish : oysgabes un forshung Jiddistik : Edition & Forschung Yiddish : Editions & Research Herausgegeben von Marion Aptroot, Efrat Gal-Ed, Roland Gruschka und Simon Neuberg Band 1 Leket : yidishe shtudyes haynt Leket : Jiddistik heute Leket : Yiddish Studies Today Bibliografijische Information Der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deut- schen Nationalbibliografijie ; detaillierte bibliografijische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © düsseldorf university press, Düsseldorf 2012 Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urhe- berrechtlich geschützt. -

Bamidbar/Shavuot

Parasha Tefilah MAY 15, 2021 Daily Bitachon 4TH OF SIVAN, 5781 Embrace Shabbat Living Emunah Halachot BAMIDBAR/SHAVUOT Visit iTorah.com for: More than 20,000 shiurim given by our Community’s leading Rabbanim; Daf Yomi program; Tehillim; Tefilot; and much more. Manage subscriptions to receive daily Halachot, weekly Parasha insights, Tehillim and Levaya notifications. In loving memory of Stanley Chera A"h - Shlomo Ben Shoshana Please treat this newsletter as you would any holy book. Discard only via Genizah IN MEMORY OF THE KEDOSHIM OF MERON ELIYAHU BEN RACHMON • MOSHE BEN SUZAN • TALIA BAT HADASSA IN HONOR OF RABBI ELI J MANSOUR BY TOMER AND TZVIYA NAFTALI Avraham Naftali - לעילוי נשמת אברהם שאול נפתלי הלוי בן שולמית ע״ה Every Jew is a Letter Jewish tradition views each Jew as a letter of the Torah. Each and every Jew, regardless of his background and cur- Rabbi Eli Mansour rent standing, has a sacred, precious soul. The Book of Bamidbar begins with a This is why, as the Torah tells in Parashat Bamidbar, God record of the census that God ordered instructed Moshe himself to personally count the nation. Moshe to take after the Mishkan’s This “counting” involved more than determining a number. construction. The census found that there were just over It entailed identifying the spiritual source of every Jew, find- 600,000 males aged twenty and over among Beneh Yisrael. ing to which “letter,” or aspect, of Torah each Jewish soul The Sages comment that the 600,000 people in Beneh Yis- corresponded. This undertaking required the involvement rael correspond to the 600,000 letters in the Torah. -

1 on Pinchas

BS"D perhaps a respected sage positioned to address the many spiritual crises that certainly will affect the nascent nation. Therefore there can be no greater expression of Moshe's commitment to To: [email protected] his approach and no greater instruction as to its importance, than to insist From: [email protected] with Hashem's consent, when the nation is experiencing formative and altogether new experiences, that the next leader be focused on the INTERNET PARSHA SHEET individual. Perhaps Moshe is stressing that ultimately our leaders will be measured by ON - 5766 PINCHAS the closeness to Hashem that their charges have achieved. This life long pursuit of "deveikus" (closeness to Hashem) varies from person to person In our 11th cycle! To receive this parsha sheet, go to http://www.parsha.net and click Subscribe or send and is crafted by personal challenges and triumphs. Thus one who has been a blank e-mail to [email protected] Please also copy me at disciplined to see and focus upon the strengths and concerns of others [email protected] A complete archive of previous issues is now available at will be invaluable in shaping lives that are meaningful and genuine in their http://www.parsha.net It is also fully searchable. quest for greater spirituality ("ruchniyus"). ________________________________________________ Copyright © 2006 by The TorahWeb Foundation. All rights reserved. Audio (MP3 and CD) - http://www.TorahWeb.org/audio Video - To sponsor an issue of the Internet Parsha Sheet (proceeds to Tzedaka) http://www.TorahWeb.org/video -

Adas Israel Congregation June 2017 / Sivan–Tammuz 5777 Chronicle

Adas Israel Congregation June 2017 / Sivan–Tammuz 5777 Chronicle Join us for our annual cantorial concert featuring the Argen-Cantors Chronicle • May 2017 • 1 The Chronicle Is Supported in Part by the Ethel and Nat Popick Endowment Fund clergycorner From the President By Debby Joseph Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt In my early years of learning meditation I studied with Rabbi David Zeller (z”l), at Yakar, a wonderful synagogue in the heart of Jerusalem. I would go to his classes once a week and listen with strong intention to try to understand the practice of meditation, a practice that was changing my everyday life. During the past two years, when people Rabbi Zeller would talk often about the concept of devekut (attachment to learned that I was president of Adas Israel God) that the Hasidic masters had brought alive from teachings in the Zohar: Congregation, they inevitably cracked a “If you are already full, there is no room for God. Empty yourself like a vessel.” joke about feeling sorry for me. Never has I would try my hardest to understand what this meant, but I could not grasp that sentiment been further from the truth. I how to embody this concept, how to make it true to my own experience. have relished serving in this role. I have met How do you empty yourself? What does that feel like? many people, shared many experiences, For many years, in my own spiritual practice, I committed myself to learning and the feelings that permeated all that has meditation, sitting for 5, 10, 20, 30 minutes in silent meditation several times happened during my tenure make up one of a week. -

The Jewish Woman in a Torah Society

TEVES, 5735 I NOV.-DEC .. 1974 VOLUME X, NUMBERS 5-6 :fHE SIXTY FIVE CENTS The Jewish Woman in a Torah Society For Frustration or Fulfillment? Of Rights & Duties The Flame of Sara S chenirer The McGraw-Hill Anti-Sexism Memo ---also--- Convention Addresses by Senior Roshei Hayeshiva THE JEWISH OBSERVER in this issue ... OF RIGHTS AND DUTIES, Mordechai Miller prepared for publication by Toby Bulman.......................... 3 COMPLETENESS OF FAITH, based on an address by Rabbi Moshe Feinstein prepared for publication by Chaim Ehrman................... 5 CHUMASH: PREPARATION FOR OUR ENCOUNTER WITH THE WORLD, based on an address by Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetsky .................................. 8 SOME THOUGHTS ON MOSHIACH based on further remarks by Rabbi Kamenetsky ............... 9 PASSING THE TEST based on an address by Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman......................... I 0 JEWISH WOMEN IN A TORAH SOCIETY FOR FRUSTRATION? OR FULFILLMENT?, THE JEWISH OBSERVER is published monthly, except July and August, Nisson Wolpin ................. ............................................... 12 by the Agudath Israel of Amercia, 5 Beekman St., New York, N. Y. A FLAME CALLED SARA SCHENIRER, Chaim Shapiro 19 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. Subscription: $6.50 per year; Two years, $11.00; BETH JACOB: A PICTORIAL FEATURE ........................ 24 Three years $15.00; outside of the United States $7 .50 per year. Single THE McGRAW HILL ANTI-SEXISM MEMO, copy sixty~five cents. Printed in the U.S.A. Bernard Fryshman ................................... .............. 26 RABBI N1ssoN WoLPIN MAN, a poem by Faigie Russak .......................................... 29 Editor Editorial Board WAITING FOR EACH OTHER DR. ERNST L. BODENHEIMER 30 Chairman a poem by Joshua Neched Yehuda .............................. RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI JOSEPH ELIAS BOOK IN REVIEW: What ls the Reason - Vols. -

December 12 2015 SB.Pub

The Jewish Center SHABBAT BULLETIN DECEMBER 12, 2015 • PARSHAT MIKETZ , S HABBAT ROSH CHODESH AND CHANUKAH • 30 K ISLEV 5776 Mazal Tov to the Kaplan family on the occasion of Einav’s Bat Mitzvah EREV SHABBAT CHANUKAH V WELCOME TO OUR COMMUNITY SCHOLAR 4:11PM Candle lighting DR. E RICA BROWN 4:15PM Minchah (3 rd floor) 7:30-9:00PM Community Chanukah Oneg WHO IS JOINING US THIS SHABBAT Teen Chanukah Lounge Seudah Shlishit: Have the Hellenists Won? Dr.Jekyll and Rabbi Hyde SHABBAT Sunday Morning 9:30am ROSH CHODESH AND CHANUKAH VI When Yaakov Met Pharaoh: Genesis 47 as a Metaphor 7:30AM Hashkama Minyan (The Max and Marion Grill Beit Midrash) for Exile and Redemption Please note earlier time. 8:30AM Rabbi Israel Silverstein Mishnayot Class with Rabbi Yosie Levine YACHAD SHABBTON 9:00AM Shacharit (3 rd floor) 9:15AM Hashkama Shiur with Rabbi Noach Goldstein (Lower Level) SHABBAT , DECEMBER 18 9:15AM Young Leadership Minyan (The Max Stern Auditorium) The JC is proud to partner with Manhattan Day 9:30AM Sof Zman Kriat Shema School and the Orthodox Union as they host their 10:00AM Youth Groups, Under age 3, 3-4-year-olds and 5-6-year-olds: annual Yachad Shabbaton. Participants will join us Geller Youth Center; 2 nd -3rd graders, 4 th -6th graders: 7 th floor Special Chanukah Programs in Youth Groups for Kabbalat Shabbat followed by a com- Community Kiddush (The Max Stern Auditorium) munal Shabbat Dinner. Sponsorship and hospitality opportunities available. For WITH THANKS TO OUR KIDDUSH SPONSORS : more information and to get involved, Chaviva, Andrew, Barak & Vered Kaplan, in honor of their contact [email protected]. -

Divrei Torah, Present- Hopeful Sign

, t'-1==··1<<~.-,.~~ . ,>.,.~... a>·>F Haolam, the most trusted name in Cholov Yisroel Kosher Cheese. A reputation earned through 25 years of scrupulous devotion to quality and kashruth. With 12 delicious varieties. Hao!am, a tradition you'll enjoy keeping. All Haolam cheese products are made in the U.S.A. under the strict rabbinical supervision of: The Rabbinate of K'hal Adath Jeshurun 1~-:v1 Washington Heights. NY Cholov l'isroel THURM BROS. WORLD CHEESE CO. INC. BROOKLYN.NY 11232 I The Thurm Families wish Kial Yisroel a nn'V1 1'\V:J ln If it has no cholesterol, a better than-butter flavor, and a reputation for kashruth you can trust... It has to be 111 I the new, improved parve I a I unsalted margarine I~~ I Under the strict Rabbinical supervision of K'hal Adas jeshurun, NY. COMMERCIAL QUALITY • INSTITUTIONAL & RESIDENTIAL • WOOD • STEEL • PLASTIC • SWINGS • SLIDES • PICNIC TABLES • SCHOOL & CAMP EQUIPMENT • BASKETBALL SYSTEMS • RUBBER FLOORING • ETC. • Equipment meets or exceeds all ASTM and CPSC safety guidelines • Site planning and design services with state-of-the-art Auto CAD • Stainless steel fabrication for I ultimate rust resistance New Expanded I Playground Showroom! I better 5302 New Utrecht Avenue• Brooklyn, NY 11219 health Phone: 718-436-480 l INSHABBOS Swimmhlg in •'".:n.o Night Hike to Sattaf Heruliya Beach MeJava Malka nan 11 July 19 nrin"1' INSHABBOS 11'#.:nJI Brieflng & Packing for South nrin t:> Aug.2 OFFSHABBOS Special Visit To Spurts & Field Day Yad Vashem! in "l/'lfl' TJ :i.K 0 Aug. 13 :i.K t Aug.