B. Development of Supply Curves for Environmental Compensation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Landeszentrale Für Politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6Th Fully Revised Edition, Stuttgart 2008

BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG A Portrait of the German Southwest 6th fully revised edition 2008 Publishing details Reinhold Weber and Iris Häuser (editors): Baden-Württemberg – A Portrait of the German Southwest, published by the Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, Director: Lothar Frick 6th fully revised edition, Stuttgart 2008. Stafflenbergstraße 38 Co-authors: 70184 Stuttgart Hans-Georg Wehling www.lpb-bw.de Dorothea Urban Please send orders to: Konrad Pflug Fax: +49 (0)711 / 164099-77 Oliver Turecek [email protected] Editorial deadline: 1 July, 2008 Design: Studio für Mediendesign, Rottenburg am Neckar, Many thanks to: www.8421medien.de Printed by: PFITZER Druck und Medien e. K., Renningen, www.pfitzer.de Landesvermessungsamt Title photo: Manfred Grohe, Kirchentellinsfurt Baden-Württemberg Translation: proverb oHG, Stuttgart, www.proverb.de EDITORIAL Baden-Württemberg is an international state – The publication is intended for a broad pub- in many respects: it has mutual political, lic: schoolchildren, trainees and students, em- economic and cultural ties to various regions ployed persons, people involved in society and around the world. Millions of guests visit our politics, visitors and guests to our state – in state every year – schoolchildren, students, short, for anyone interested in Baden-Würt- businessmen, scientists, journalists and numer- temberg looking for concise, reliable informa- ous tourists. A key job of the State Agency for tion on the southwest of Germany. Civic Education (Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg, LpB) is to inform Our thanks go out to everyone who has made people about the history of as well as the poli- a special contribution to ensuring that this tics and society in Baden-Württemberg. -

The Stuttgart Region – Where Growth Meets Innovation Design: Atelier Brückner/Ph Oto: M

The Stuttgart Region – Where Growth Meets Innovation oto: M. Jungblut Design: Atelier Brückner/Ph CERN, Universe of Particles/ Mercedes-Benz B-Class F-Cell, Daimler AG Mercedes-Benz The Stuttgart Region at a Glance Situated in the federal state of Baden- The Stuttgart Region is the birthplace and Württemberg in the southwest of Germa- home of Gottlieb Daimler and Robert ny, the Stuttgart Region comprises the Bosch, two important figures in the history City of Stuttgart (the state capital) and its of the motor car. Even today, vehicle five surrounding counties. With a popula- design and production as well as engineer- tion of 2.7 million, the area boasts a highly ing in general are a vital part of the region’s advanced industrial infrastructure and economy. Besides its traditional strengths, enjoys a well-earned reputation for its eco- the Stuttgart Region is also well known nomic strength, cutting-edge technology for its strong creative industries and its and exceptionally high quality of life. The enthusiasm for research and development. region has its own parliamentary assembly, ensuring fast and effective decision-mak- All these factors make the Stuttgart ing on regional issues such as local public Region one of the most dynamic and effi- transport, regional planning and business cient regions in the world – innovative in development. approach, international in outlook. Stuttgart Region Key Economic Data Population: 2.7 million from 170 countries Area: 3,654 km2 Population density: 724 per km2 People in employment: 1.5 million Stuttgart Region GDP: 109.8 billion e Corporate R&D expenditure as % of GDP: 7.5 Export rate of manufacturing industry: 63.4 % Productivity: 72,991 e/employee Per capita income: 37,936 e Data based on reports by Wirtschaftsförderung Region Stuttgart GmbH, Verband Region Stuttgart, IHK Region Stuttgart and Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg, 2014 Stuttgart-Marketing GmbH Oliver Schuster A Great Place to Live and Work Top Quality of Life Germany‘s Culture Capitals 1. -

Bewerbungsbroschüre-Teil 2.Pdf

Das Mühlenviertel zwischen Steilhang und Ludwigsburger Straße soll städtebaulich und freiraumplanerisch umstrukturiert und neugestaltet werden. Hierzu erfolgte bereits ein städte- baulicher Wettbewerb. Ziel ist die Aufwertung des Ortseingangs durch einen attraktiven Stadteingangsplatz mit Aufenthalts- charakter. Die Planung soll in Einklang mit dem Neubau eines Fabrikverkauf-Gebäudes der ansässigen Lederfabrik Oehler erfolgen. Durch eine neue Fußgängerüberquerung bzw. -unterquerung der Landesstraße L1100 (Ludwigsburger Straße) soll in Verbin- dung mit einem neuen Schrägaufzug am Hang die lang er- sehnte barrierefreie Fußwegeverbindung von der Altstadt zum Neckarufer geschaffen werden. Konzeption. Daueranlagen. 49 Marbach am Neckar. Neckarwiese. Die Marbacher Neckaraue ist bereits heute das Naherholungs- gebiet der Marbacher und nicht nur durch den ansässigen Biergarten und die Vereinsgebäude des Rudervereins und des Kanuclubs ein beliebtes Ausflugsziel. Das Naturdenkmal „Fischerwert“ ist als Relikt eines natürlichen Auwaldes ein be- deutender Lebensraum für die lokale Flora und Fauna und unbedingt erhaltenswert. Eine neue Fußwegebrücke bei der Schleuse über den Neckar könnte in Verbindung mit einer evtl. neuen Seilbahn den Marbacher und Benninger Bürgerinnen und Bürgern sowie Besucherinnen und Besuchern, die über den Neckartalradweg ankommen, ganz neue Möglichkeiten der Mobilität eröffnen. Es wird angestrebt die Brücke im Zusammenhang mit der geplanten Verlängerung der Schleuse umzusetzen. So könnte man nun fußläufig und barrierefrei innerhalb kürzester Zeit vom Schul- und Sportzentrum über den Literaturpark und die Schillerhöhe bis zum Benninger Neckarufer gelangen und umgekehrt. Die Neckarinsel soll dabei als Rückzugsort für die Natur belassen werden. Zusätzlich zur evtl. Seilbahn soll auch ein neuer Fußweg südwestlich des Schiller-National- museums die Schillerhöhe mit der Neckaraue verbinden. Die strukturarmen Wiesenflächen in der Aue sollen durch die Neupflanzung von Bäumen aufgewertet werden. -

Tagesbericht COVID-19 Baden-Württemberg 15.08.2020

Referat 92: Epidemiologie und Gesundheitsschutz Tagesbericht COVID-19 Samstag, 15.08.2020, 16:00 Fallzahlen bestätigter SARS-CoV-2-Infektionen Baden-Württemberg Bestätigte Fälle Verstorbene** Genesene*** 38.483 (+58*) 1.859 (+0*) 35.396 (+74*) Geschätzter 4-Tages-R-Wert Geschätzter 7-Tages-R-Wert 7-Tage-Inzidenz am 11.08.2020 am 10.08.2020 Baden-Württemberg 1,22 (0,90 - 1,59) 1,26 (1,07 - 1,50) 5,4 *Änderung gegenüber dem letzten Bericht vom 14.08.2020; ** verstorben mit und an SARS-CoV-2; *** Schätzwert 1500 Bisherige Fälle Neue Fälle 1000 500 Anzahl gemeldete SARS-CoV-2 Fälle 0 02.Jul 06.Jul 10.Jul 14.Jul 18.Jul 22.Jul 26.Jul 30.Jul 01.Apr 05.Apr 09.Apr 13.Apr 17.Apr 21.Apr 25.Apr 29.Apr 03.Mai 07.Mai 11.Mai 15.Mai 19.Mai 23.Mai 27.Mai 31.Mai 04.Jun 08.Jun 12.Jun 16.Jun 20.Jun 24.Jun 28.Jun 04.Mrz 08.Mrz 12.Mrz 16.Mrz 20.Mrz 24.Mrz 28.Mrz 25.Feb 29.Feb 03.Aug 07.Aug 11.Aug 15.Aug Abb.1: Anzahl der an das LGA übermittelten SARS-CoV-2 Fälle nach Meldedatum (blau: bisherige Fälle; gelb: neu übermittelte Fälle), Baden-Württemberg, Stand: 15.08.2020, 16:00 Uhr. Hinweis: Das Meldedatum entspricht dem Datum, an dem das jeweilige Gesundheitsamt vor Ort Kenntnis von einem positiven Laborbefund erhalten hat. Die Übermittlung an das LGA erfolgt nicht immer am gleichen Tag. Besondere Ereignisse Keine. Änderungen gegenüber dem Stand vom letzten Bericht werden blau dargestellt. -

Welcome to the Goeppingen D

Welcome! Information and initial advice for international skilled specialists The Stuttgart Region Welcome Service is an offering by Stuttgart Region Skilled Specialists Alliance (Fachkräfte- on arriving, living and working allianz Region Stuttgart) under the sponsorship of Stuttgart Region Economic Development Corporation (Wirtschafts- förderung Region Stuttgart GmbH). From October 2015, the Stuttgart Region Welcome Service will provide a regional Baden-Württemberg’s Ministry of Finance funds the advisory service in the districts Böblingen, Stuttgart Region Welcome Service using finance provided Welcome Service Region Stuttgart Esslingen, Göppingen, Ludwigsburg and by the State of Baden-Württemberg. Rems-Murr. We give information in German, English, Spanish, French, Russian, Italian and Portuguese. Welcome to the Göppingen district Target group International skilled specialists, students Information and initial advice and their family members who wish to Contact for international skilled specialists live and work in the Stuttgart Region. Meike Augustin on arriving, living and working Tel. +49 711 22835-879 [email protected] Topics Wirtschaftsförderung Arriving, studying, working, learning Region Stuttgart GmbH German, obtaining professional skills, Welcome Service Region Stuttgart recognition of foreign qualifications, Friedrichstraße 10 residency law, school, living, clubs, culture 70174 Stuttgart in the Stuttgart Region. wrs.region-stuttgart.de Printed on paper with FSC certification stamp, www.fsc.org; Photo © Rawpixel/Fotolia.com Printed on paper with FSC certification stamp, www.fsc.org; welcome.region-stuttgart.de wrs_flyer_welcome_LK_Gp_engl_05.indd 1-3 28.09.15 11:34 Advisory service Contact persons Stuttgart Welcome Center in the Göppingen district in the Göppingen district Appointments Wednesday Landratsamt Göppingen Finanzamt Göppingen Outside of the regional opening times, you can (once a month) Lorcher Straße 6 (Tax office) use the offering of the Stuttgart Welcome Center. -

Orientation Plan Driving Directions

Directions to Klinikum Nordschwarzwald Calw-Hirsau Calw Klinikum Nordschwarzwald Bruchsal Heilbronn Bretten Karlsruhe A5 294 A81 A8 A8 Ettlingen Pforzheim Ludwigsburg A5 Klinikum Nordschwarzwald Leonberg 294 Calmbach 295 Stuttgart Baden-Baden Bad Wildbad 296 Sindelfingen Freiburg Calw 463 Böblingen 294 Herrenberg Tübingen Nagold 28 28 Freudenstadt Horb Reutlingen A81 Coming from Calmbach: In the centre of Calmbach change B 294 to B 296 in the direction Calw, drive through Oberreichenbach and 1 km outside the village turn left towards Klinikum Nordschwarzwald. Coming from Hirsau: Klinikum Nordschwarzwald Drive on the B 296 in the direction Oberreichenbach, after about 5 km branch off towards Klinikum Im Lützenhardter Hof Nordschwarzwald. 75365 Calw-Hirsau Tel.: 07051 586-0 Klinikum Fax.: 07051 586-2700 Calmbach Nordschwarzwald [email protected] Bad Liebenzell 296 www.kn-calw.de Oberkollbach 463 Bad Wildbad Hirsau Oberreichenbach Rechtsfähige Anstalt des öffentlichen Rechts Calw Geschäftsführer: Prof. Dr. Dr. Hans-Jürgen Seelos 294 463 Ein Unternehmen der ZfP-Gruppe Baden-Württemberg Orientation Plan Driving Directions . Sitemap 9 Paediatric psychiatry and Orientation Plan psychotherapy - station 60 10 Gymnasium 11 Playing fields 10 12 Residential area „Lützenhardter Hof“ 11 19 9 13 Nurse’s training school 8 20 14 Social counselling (house 16) 12 21 17 6 15 Ergotherapy, art therapy 7 16 H 13 18 P i 3 5 16 Work therapy “paper”, 15 14 art therapy, 4 car pool, trade workshops i i 2 17 Work therapy “textiles”/“metal”, i H kitchen, bakery 1 P -

Eli Rosenbaum, Ludwigsburg, Germany

Festakt und Symposium aus Anlass des 50-Ohrigen Bestehens der Zentralen Stelle der Landesjustizverwaltungen zur Aufk1Hrung nationalsozialistischer Verbrechen am 1. und 2. Dezember 2008 in Ludwigsburg • ••0,• • •• e ••* • •• • •• Jusltiz, die: [zu 1st. •• • • • • • ustilia = GereChtigkeit, * * • s. ' • Rechtl: 1. Rec tswesen, • 1051110161! pfiege: Rechts rechung; • 0 • • • • • 0• •• •• rechisprechende Gewa lt • • 5 551 • • • II in einem &clot &horde, •• •• •• •• •* Gesam theft der ehordent 6110.40e.' die far die Aus iug der IwoID •• •. verantwoi riich ist. #41*•** iPO. e• • •w • ▪• 0 500 . • • • * •; • • • • • • * • S 0, * • * * 0 • • • 0 • * • • s • • • * • • 5*.* • * **• • • • * • * * * • • * a • * • * • it • • • e • • • • • • e • • • • • • • • • it • • • • • • 0 • • • • • • 0.* * • • • • a• • .4,• 0. * * . • • ••• •IS • •le Die Ausstrahlung der Zentralen Stelle auf die juristische und gesellschaftliche Auseinandersetzung mit der NS-Verbrechensgeschichte Baden-Wurttemberg Justizministerium DOKUMENTATION Festakt und Symposium aus Anlass des 50-jahrigen Bestehens der Zentralen Stelle der Landesjustizverwaltungen zur Auflclitung nationalsozialistischer Verbrechen am 1. und 2. Dezember 2008 in Ludwigsburg Die Ausstrahlung der Zentralen SteIle auf die juristische und gesellschaftliche Auseinandersetzung mit der NS-Verbrechensgeschichte 3 INHALTSVERZEICHNIS I. FESTAKT Programm Begriillung 11 Prof. Dr. Ulrich Go11 MdL Stellvertretender Ministerprisident und Justizminister des Landes Baden-Wiirttemberg Grufiworte 19 Aufarbeitung, damit Menschen -

Karte Der Erdbebenzonen Und Geologischen Untergrundklassen

Karte der Erdbebenzonen und geologischen Untergrundklassen 350 000 KARTE DER ERDBEBENZONEN UND GEOLOGISCHEN UNTERGRUNDKLASSEN FÜR BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG 1: für Baden-Württemberg 10° 1 : 350 000 9° BAYERN 8° HESSEN RHEINLAND- PFALZ WÜRZBUR G Die Karte der Erdbebenzonen und geologischen Untergrundklassen für Baden- Mainz- Groß- Main-Spessart g Wertheim n Württemberg bezieht sich auf DIN 4149:2005-04 "Bauten in deutschen Darmstadt- li Gerau m Bingen m Main Kitzingen – Lastannahmen, Bemessung und Ausführung üblicher Freudenberg Erdbebengebieten Mü Dieburg Ta Hochbauten", herausgegeben vom DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V.; ub Kitzingen EIN er Burggrafenstr. 6, 10787 Berlin. RH Alzey-Worms Miltenberg itz Die Erdbebenzonen beruhen auf der Berechnung der Erdbebengefährdung auf Weschn Odenwaldkreis Main dem Niveau einer Nicht-Überschreitenswahrscheinlichkeit von 90 % innerhalb Külsheim Werbach Großrinderfeld Erbach Würzburg von 50 Jahren für nachfolgend angegebene Intensitätswerte (EMS-Skala): Heppenheim Mud Pfrimm Bergst(Bergstraraßeß) e Miltenberg Gebiet außerhalb von Erdbebenzonen Donners- WORMS Tauberbischofsheim Königheim Grünsfeld Wittighausen Gebiet sehr geringer seismischer Gefährdung, in dem gemäß Laudenbach Hardheim des zugrunde gelegten Gefährdungsniveaus rechnerisch die bergkreis Höpfingen Hemsbach Main- Intensität 6 nicht erreicht wird Walldürn zu Golla Bad ch Aisch Lauda- Mergentheim Erdbebenzone 0 Weinheim Königshofen Neustadt Gebiet, in dem gemäß des zugrunde gelegten Gefährdungsniveaus Tauber-Kreis Mudau rechnerisch die Intensitäten 6 bis < 6,5 zu erwarten sind FRANKENTHAL Buchen (Odenwald) (Pfalz) Heddes-S a. d. Aisch- Erdbebenzone 1 heim Ahorn RHirschberg zu Igersheim Gebiet, in dem gemäß des zugrunde gelegten Gefährdungsniveaus an der Bergstraße Eberbach Bad MANNHEIM Heiligkreuz- S c Ilves- steinach heff Boxberg Mergentheim rechnerisch die Intensitäten 6,5 bis < 7 zu erwarten sind Ladenburg lenz heim Schriesheim Heddesbach Weikersheim Bad Windsheim LUDWIGSHAFEN Eberbach Creglingen Wilhelmsfeld Laxb Rosenberg Erdbebenzone 2 a. -

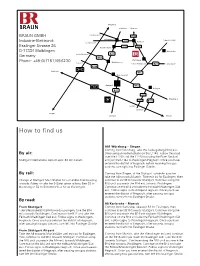

How to Find Us

Würzburg Heilbronn Marbach Ludwigsburg-Nord BRAUN GMBH L1100 Ludwigsburg Schwäbisch Hall L1140 Remseck Industrie-Elektronik Ludwigsburg-Süd L1144 L1142 Esslinger Strasse 26 Kornwestheim D-71334 Waiblingen Winnenden Korntal-Münchingen B27 Germany B10 Waiblingen Phone: +49 (0)7151/956230 Zuenhausen Weilimdorf Fellbach-Waiblingen Süd B29 Schorndorf B295 A81 Karlsruhe B14 Bad Cannstatt Stuttgart A8 B10 Esslingen B27 L1192 Göppingen L1202 B313 Esslingen Wendlingen Singen Tübingen Munich How to find us A81 Würzburg – Singen Coming from Würzburg, take the Ludwigsburg-Nord exit. By air: Drive across Friedrichstraße on the L1140. Follow this road over the L1100 and the L1140 (crossing the River Neckar) Stuttgart International Airport appr. 30 km distant. and join the L1142 to Waiblingen-Hegnach. Once you have entered the district of Hegnach, before reaching two gas stations, turn right into Esslinger Straße. By rail: Coming from Singen, at the Stuttgart autobahn junction take the A8 towards Munich. Take exit 54 for Esslingen, then Change at Stuttgart Main Station for a mainline train heading continue to exit B10 towards Stuttgart. Continue along the towards Aalen, or take the S-Bahn urban railway (line S3 to B10 until you reach the B14 exit towards Waiblingen. Backnang or S2 to Schorndorf) as far as Waiblingen. Continue on the B14 and take the Fellbach/Waiblingen Süd exit. Follow signs to Waiblingen-Hegnach. Once you have entered the district of Hegnach, after passing two gas stations, turn left into Esslinger Straße. By road: A8 Karlsruhe – Munich From Stuttgart Coming from Karlsruhe, take exit 54 for Esslingen, then Take Uferstraße/B10/B14 towards Esslingen, take the B14 continue to exit B10 towards Stuttgart. -

Making a Smooth Transition – Information About School and Work for New Immigrants

Making a Smooth Transition – Information about School and Work for New Immigrants Making a Smooth Transition Introduction Dear Sir or Madam, “Education is the key to integration” – you may already have heard these or similar phrases since your arrival in Germany. And in fact, it is very important to get to know and understand the German education system with all it has to offer in terms of training, continuing education and further development in order to be able to gain a lasting foothold in Germany. As you have just arrived in Germany, we want this brochure to help you and your children learn about the important contact centres and advisory services. Integration through education only succeeds if all the relevant parties work together and the supporting services are known. With our series of publications, we want to play our part in helping to support you on your way to a self-determined and independent life in our district. This brochure will inform you about your “smooth transition” in Esslingen district. It is intended to help you as parents feel at home quickly and easily. My heartfelt thanks go to everyone who has helped to produce the brochure. Katharina Kiewel Head of Social Services Dieses Vorhaben wird aus Mitteln des Bundes- ministeriums für Bildung und Forschung gefördert. The project is supported by funding from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research. 2 Transition from School to Work 3 Übergang Schule – Beruf 2 Übergang Schule – Beruf 3 Tables of Contents 06 1. School education 26 5. Financing opportunities during the training 06 ▪ Recognition of school-leaving qualifications 28 ▪ Education and Participation (BuT) 07 ▪ Recognition of school-leaving qualifications for university entrance qualifications 29 ▪ Vocational Training Assistance (BAB) 08 ▪ School attendance in Germany 30 ▪ Training Assistance Act (BAföG) 31 ▪ Other financing opportunities 12 2. -

Die Stadt Ludwigsburg

Statistisches Monatsheft Baden-Württemberg 1/2019 Land, Kommunen Im Blickpunkt: Die Stadt Ludwigsburg Reinhard Güll In der Serie „Im Blickpunkt“ steht dieses Mal terer SBahnHaltepunkt ist Favoritepark der die Stadt Ludwigsburg im gleichnamigen Kreis. Linie S4. Den öffentlichen Personennahver Aus dem Landesinformationssystem Baden- kehr bedienen die Stadtbuslinien verschiedener Württemberg (LIS) lassen sich für Ludwigs- Firmen darüber hinaus gibt es mehrere Über burg wie für jede andere Gemeinde des Lan- landbuslinien der Regiobus Stuttgart GmbH. des interessante Erkenntnisse zur Struktur und Entwicklung gewinnen. Besonders heraus- Auf der Gemarkung von Ludwigsburg im Schlöss gehoben werden an dieser Stelle die Bevölke- lesfeld wurden 1965 viele Besiedlungsspuren rungsentwicklung, die Wohn- und die Be- aus der Jungsteinzeit gefunden. Dieses Gebiet Reinhard Güll war Büroleiter schäftigtensituation. war von 5700 v. Chr. bis 3300 v. Chr von Sied der Abteilung „Informations- lern der Bandkeramik bewohnt. Auch zahlreiche dienste, sozial- und regional- wissenschaftliche Analysen“ Funde auf dem Ludwigsburger Stadtgebiet und im Statistischen Landesamt Ludwigsburg ist eine Stadt nördlich von Stutt der näheren Umgebung belegen keltische Sied Baden-Würt temberg. gart. Sie gehört zur Region Stuttgart und zur lungsaktivitäten. Gegen Ende des 1. Jahrhun europäischen Metropolregion Stuttgart. Lud derts unserer Zeitrechnung besetzten die Römer wigsburg ist die Kreisstadt und größte Stadt die Region, so stammt aus römischer Zeit eine des Landkreises Ludwigsburg. Zusammen mit villa rustica, die im Stadtteil Hoheneck entdeckt Kornwestheim bildet Ludwigsburg ein Mittel wurde. Ludwigsburg ist nicht wie die meisten zentrum für die umliegenden Gemeinden. Zum Städte in Deutschland über Jahrhunderte ge Mittelbereich Ludwigsburg/Kornwestheim ge wachsen, sondern wurde Anfang des 18. Jahr hören noch die Städte und Gemeinden Affal hunderts am Reißbrett geplant. -

Die Naturschutzverbände Im Rems-Murr-Kreis

Die Naturschutzverbände im Rems-Murr-Kreis LNV-Arbeitskreis Rems-Murr-Kreis Stand Mai 2016 Die Naturschutzverbände im Rems-Murr-Kreis Landesnaturschutzverband Baden-Württemberg (LNV) • LNV-Arbeitskreis Rems-Murr-Kreis;Treffen alle zwei Monate • BUND, Kreisverband Rems-Murr-Kreis • NABU, Kreisverband Rems-Murr-Kreis • NaturFreunde, Kreisverband Rems-Murr • Schwäbischer Albverein, Rems-Murr-Gau • Bund Naturschutz Alb Neckar, Arbeitsgruppe Remstal • Landesjagverband, Kreisjägerverband • Landesfischereiverband • Schutzgemeinschaft Deutscher Wald, Rems-Murr 2 LNV-Arbeitskreis Rems-Murr-Kreis Arbeitstreffen der Verbände im Rems-Murr-Kreis zum Erfahrungsaustausch • Erarbeitung gemeinsamer Stellungnahmen zu • Änderungen Flächennutzungsplänen, • Eingriffe in Naturschutzgebiete • Hochwasserrückhaltebecken • Scopingtermine • Bebauungsplänen. • Aktuelle Themen u.a. ikG2019, Windkraftanlagen • Kontakte zu den Ämtern beim Landratsamt, Kommunen, Landschaftserhaltungsverband und dem RP Stuttgart 3 Schutzgemeinschaft Deutscher Wald e.V. Kreisverband Rems-Murr (www.SDW-Rems-Murr.de) Unsere Schwerpunkte Einzelveranstaltungen für unterschiedliche Zielgruppen Mehrjährige + Dauer-Projekte NaTour-Spaziergänge (barrierefrei) Für und mit Schulen und Kindergärten Besichtigungen (Sägewerke, Holzverarbeitende Betriebe, STIHL, Holz-Submissionsplatz) Vorträge („Natur vor der Haustür“) Wald- und Wildnisprojekt Freundeskreis Asyl (Asylsuchende) (Tausschule, Janusz-Korczak-Schule) Waldfotografie Wild auf Wald (Schillerschule) Single Trail (Singles) Waldentdecker