Eli Rosenbaum, Ludwigsburg, Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Running Head: the TRAGEDY of DEPORTATION 1

Running head: THE TRAGEDY OF DEPORTATION 1 The Tragedy of Deportation An Analysis of Jewish Survivor Testimony on Holocaust Train Deportations Connor Schonta A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 THE TRAGEDY OF DEPORTATION 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ David Snead, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Christopher Smith, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Mark Allen, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date THE TRAGEDY OF DEPORTATION 3 Abstract Over the course of World War II, trains carried three million Jews to extermination centers. The deportation journey was an integral aspect of the Nazis’ Final Solution and the cause of insufferable torment to Jewish deportees. While on the trains, Jews endured an onslaught of physical and psychological misery. Though most Jews were immediately killed upon arriving at the death camps, a small number were chosen to work, and an even smaller number survived through liberation. The basis of this study comes from the testimonies of those who survived, specifically in regard to their recorded experiences and memories of the deportation journey. This study first provides a brief account of how the Nazi regime moved from methods of emigration and ghettoization to systematic deportation and genocide. Then, the deportation journey will be studied in detail, focusing on three major themes of survivor testimony: the physical conditions, the psychological turmoil, and the chaos of arrival. -

The Stuttgart Region – Where Growth Meets Innovation Design: Atelier Brückner/Ph Oto: M

The Stuttgart Region – Where Growth Meets Innovation oto: M. Jungblut Design: Atelier Brückner/Ph CERN, Universe of Particles/ Mercedes-Benz B-Class F-Cell, Daimler AG Mercedes-Benz The Stuttgart Region at a Glance Situated in the federal state of Baden- The Stuttgart Region is the birthplace and Württemberg in the southwest of Germa- home of Gottlieb Daimler and Robert ny, the Stuttgart Region comprises the Bosch, two important figures in the history City of Stuttgart (the state capital) and its of the motor car. Even today, vehicle five surrounding counties. With a popula- design and production as well as engineer- tion of 2.7 million, the area boasts a highly ing in general are a vital part of the region’s advanced industrial infrastructure and economy. Besides its traditional strengths, enjoys a well-earned reputation for its eco- the Stuttgart Region is also well known nomic strength, cutting-edge technology for its strong creative industries and its and exceptionally high quality of life. The enthusiasm for research and development. region has its own parliamentary assembly, ensuring fast and effective decision-mak- All these factors make the Stuttgart ing on regional issues such as local public Region one of the most dynamic and effi- transport, regional planning and business cient regions in the world – innovative in development. approach, international in outlook. Stuttgart Region Key Economic Data Population: 2.7 million from 170 countries Area: 3,654 km2 Population density: 724 per km2 People in employment: 1.5 million Stuttgart Region GDP: 109.8 billion e Corporate R&D expenditure as % of GDP: 7.5 Export rate of manufacturing industry: 63.4 % Productivity: 72,991 e/employee Per capita income: 37,936 e Data based on reports by Wirtschaftsförderung Region Stuttgart GmbH, Verband Region Stuttgart, IHK Region Stuttgart and Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg, 2014 Stuttgart-Marketing GmbH Oliver Schuster A Great Place to Live and Work Top Quality of Life Germany‘s Culture Capitals 1. -

Operation Reinhard: Death Camps What’S Included

World War Two Tours Operation Reinhard: Death Camps What’s included: Hotel Bed & Breakfast All transport from the official overseas start point Accompanied for the trip duration All Museum entrances All Expert Talks & Guidance Low Group Numbers “Amazing time, one of those ‘once in a life time trips’. WelI organised, very interesting and thoroughly enjoyable. I would recommend the trip to any enthusiast.” Operation Reinhard (German: Aktion Reinhard or Einsatz Reinhard) was the code name given to the Nazi plan to murder Polish Jews in the General Government, and marked the most deadly phase of the Holocaust, the use of extermination camps. During the operation, as many as two Military History Tours is all about the ‘experience’. Naturally we take million people were murdered in Bełżec, Sobibor and Treblinka, almost all of whom were Jews. care of all local accommodation, transport and entrances but what By 1942, the Nazis had decided to undertake the Final Solution. sets us aside is our on the ground knowledge and contacts, established This led to the establishment of camps such as Bełżec, over many, many years that enable you to really get under the surface of Sobibor and Treblinka which had the express purpose of killing your chosen subject matter. thousands of people quickly and efficiently. These sites differed By guiding guests around these from those such as Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek because historic locations we feel we are contributing greatly towards ‘keeping they also operated as forced-labour camps, these were purely the spirit alive’ of some of the most killing factories. The organizational apparatus behind the memorable events in human history. -

Tagesbericht COVID-19 Baden-Württemberg 15.08.2020

Referat 92: Epidemiologie und Gesundheitsschutz Tagesbericht COVID-19 Samstag, 15.08.2020, 16:00 Fallzahlen bestätigter SARS-CoV-2-Infektionen Baden-Württemberg Bestätigte Fälle Verstorbene** Genesene*** 38.483 (+58*) 1.859 (+0*) 35.396 (+74*) Geschätzter 4-Tages-R-Wert Geschätzter 7-Tages-R-Wert 7-Tage-Inzidenz am 11.08.2020 am 10.08.2020 Baden-Württemberg 1,22 (0,90 - 1,59) 1,26 (1,07 - 1,50) 5,4 *Änderung gegenüber dem letzten Bericht vom 14.08.2020; ** verstorben mit und an SARS-CoV-2; *** Schätzwert 1500 Bisherige Fälle Neue Fälle 1000 500 Anzahl gemeldete SARS-CoV-2 Fälle 0 02.Jul 06.Jul 10.Jul 14.Jul 18.Jul 22.Jul 26.Jul 30.Jul 01.Apr 05.Apr 09.Apr 13.Apr 17.Apr 21.Apr 25.Apr 29.Apr 03.Mai 07.Mai 11.Mai 15.Mai 19.Mai 23.Mai 27.Mai 31.Mai 04.Jun 08.Jun 12.Jun 16.Jun 20.Jun 24.Jun 28.Jun 04.Mrz 08.Mrz 12.Mrz 16.Mrz 20.Mrz 24.Mrz 28.Mrz 25.Feb 29.Feb 03.Aug 07.Aug 11.Aug 15.Aug Abb.1: Anzahl der an das LGA übermittelten SARS-CoV-2 Fälle nach Meldedatum (blau: bisherige Fälle; gelb: neu übermittelte Fälle), Baden-Württemberg, Stand: 15.08.2020, 16:00 Uhr. Hinweis: Das Meldedatum entspricht dem Datum, an dem das jeweilige Gesundheitsamt vor Ort Kenntnis von einem positiven Laborbefund erhalten hat. Die Übermittlung an das LGA erfolgt nicht immer am gleichen Tag. Besondere Ereignisse Keine. Änderungen gegenüber dem Stand vom letzten Bericht werden blau dargestellt. -

Appendix 1: Sample Docum Ents

APPENDIX 1: SAMPLE DOCUMENTS Figure 1.1. Arrest warrant (Haftbefehl) for Georg von Sauberzweig, signed by Morgen. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde 129 130 Appendix 1 Figure 1.2. Judgment against Sauberzweig. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde Appendix 1 131 Figure 1.3. Hitler’s rejection of Sauberzweig’s appeal. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin-Lichterfelde 132 Appendix 1 Figure 1.4. Confi rmation of Sauberzweig’s execution. Courtesy of Bundesarchiv Berlin- Lichterfelde Appendix 1 133 Figure 1.5. Letter from Morgen to Maria Wachter. Estate of Konrad Morgen, courtesy of the Fritz Bauer Institut APPENDIX 2: PHOTOS Figure 2.1. Konrad Morgen 1938. Estate of Konrad Morgen, courtesy of the Fritz Bauer Institut 134 Appendix 2 135 Figure 2.2. Konrad Morgen in his SS uniform. Estate of Konrad Morgen, courtesy of the Fritz Bauer Institut 136 Appendix 2 Figure 2.3. Karl Otto Koch. Courtesy of the US National Archives Appendix 2 137 Figure 2.4. Karl and Ilse Koch with their son, at Buchwald. Corbis Images Figure 2.5. Odilo Globocnik 138 Appendix 2 Figure 2.6. Hermann Fegelein. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Figure 2.7. Ilse Koch. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Appendix 2 139 Figure 2.8. Waldemar Hoven. Courtesy of Yad Vashem Figure 2.9. Christian Wirth. Courtesy of Yad Vashem 140 Appendix 2 Figure 2.10. Jaroslawa Mirowska. Private collection NOTES Preface 1. The execution of Karl Otto Koch, former commandant of Buchenwald, is well documented. The execution of Hermann Florstedt, former commandant of Majdanek, is disputed by a member of his family (Lindner (1997)). -

Welcome to the Goeppingen D

Welcome! Information and initial advice for international skilled specialists The Stuttgart Region Welcome Service is an offering by Stuttgart Region Skilled Specialists Alliance (Fachkräfte- on arriving, living and working allianz Region Stuttgart) under the sponsorship of Stuttgart Region Economic Development Corporation (Wirtschafts- förderung Region Stuttgart GmbH). From October 2015, the Stuttgart Region Welcome Service will provide a regional Baden-Württemberg’s Ministry of Finance funds the advisory service in the districts Böblingen, Stuttgart Region Welcome Service using finance provided Welcome Service Region Stuttgart Esslingen, Göppingen, Ludwigsburg and by the State of Baden-Württemberg. Rems-Murr. We give information in German, English, Spanish, French, Russian, Italian and Portuguese. Welcome to the Göppingen district Target group International skilled specialists, students Information and initial advice and their family members who wish to Contact for international skilled specialists live and work in the Stuttgart Region. Meike Augustin on arriving, living and working Tel. +49 711 22835-879 [email protected] Topics Wirtschaftsförderung Arriving, studying, working, learning Region Stuttgart GmbH German, obtaining professional skills, Welcome Service Region Stuttgart recognition of foreign qualifications, Friedrichstraße 10 residency law, school, living, clubs, culture 70174 Stuttgart in the Stuttgart Region. wrs.region-stuttgart.de Printed on paper with FSC certification stamp, www.fsc.org; Photo © Rawpixel/Fotolia.com Printed on paper with FSC certification stamp, www.fsc.org; welcome.region-stuttgart.de wrs_flyer_welcome_LK_Gp_engl_05.indd 1-3 28.09.15 11:34 Advisory service Contact persons Stuttgart Welcome Center in the Göppingen district in the Göppingen district Appointments Wednesday Landratsamt Göppingen Finanzamt Göppingen Outside of the regional opening times, you can (once a month) Lorcher Straße 6 (Tax office) use the offering of the Stuttgart Welcome Center. -

Peter Black Odilo Globocnik, Nazi Eastern Policy, and the Implementation of the Final Solution

www.doew.at – Dokumentationsarchiv des österreichischen Widerstandes (Hrsg.), Forschungen zum Natio- nalsozialismus und dessen Nachwirkungen in Österreich. Festschrift für Brigitte Bailer, Wien 2012 91 Peter Black Odilo Globocnik, Nazi Eastern Policy, and the Implementation of the Final Solution During the spring of 1943, while on an inspection tour of occupied Poland that included a briefing on the annihilation of the Polish Jews, SS Personnel Main Office chief Maximilian von Herff characterized Lublin District SS and Police Leader and SS-Gruppenführer Odilo Globocnik, in the following way: “A man fully charged with all possible light and dark sides. Little concerned with ap- pearances, fanatically obsessed with the task, [he] engages himself to the limit without concern for health or superficial recognition. His energy drives him of- ten to breach existing boundaries and to forget the boundaries established for him within the [SS-] Order – not out of personal ambition, but much more for the sake of his obsession with the matter at hand. His success speaks unconditionally for him.”1 Von Herff’s analysis of Globocnik’s reflected a consistent pattern in the ca- reer of the Nazi Party organizer and SS officer, who characteristically atoned for his transgressions of the National Socialist code of behavior by fanatical pursuit and implementation of core Nazi goals.2 Globocnik was born to Austro-Croat parents on April 21, 1904 in multina- tional Trieste, then the principal seaport of the Habsburg Monarchy. His father’s family had come from Neumarkt (Tržič), in Slovenia. Franz Globocnik served as a Habsburg cavalry lieutenant and later a senior postal official; he died of pneumonia on December 1, 1919. -

Holocaust Documents

The Holocaust The Holocaust is a period in European history that took place in Nazi Germany during the late 1930s and 1940s, just prior to and during World War II. It is important for all people to have an understanding of this genocide. This packet contains a large amount of primary and secondary source information. You should familiarize yourself with this for our discussion. My expectations for this 45 minute Harkness Table are high. I want to hear evidence of your reading and understanding of what happened in the holocaust. This packet is yours to keep. Feel free to mark it up. You may consider using a highlighter; post it notes, something to organize your research and studying so you may be able to hold an intellectual and informed discussion. Additionally, on the day you are not participating in the circle you will need to be contributing to the Google back channel discussion. Please bring your electronic device, phone, tablet, and laptop, whatever you have, to the class. I will be looking for your active engagement in the virtual discussion outside the circle. To view a timeline of the events that you are studying please visit the following webpage: http://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/holocaust/timeline.html To view images of the Holocaust and German occupation please visit the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum at the following link: http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/media_list.php?MediaType=ph Some thoughts and questions to consider when you are preparing: • Who were the Nazis? • What did they stand for? • When did they take control in Germany? • Who was Adolph Hitler? • Who was responsible for the destruction of millions of Jews, Poles, Gypsies, and other groups during World War II? • How could this happen? • Why didn’t the allies do anything to stop it? The Wannsee Protocols On January 20, 1942, an extraordinary 90-minute meeting took place in a lakeside villa in the wealthy Wannsee district of Berlin. -

Orientation Plan Driving Directions

Directions to Klinikum Nordschwarzwald Calw-Hirsau Calw Klinikum Nordschwarzwald Bruchsal Heilbronn Bretten Karlsruhe A5 294 A81 A8 A8 Ettlingen Pforzheim Ludwigsburg A5 Klinikum Nordschwarzwald Leonberg 294 Calmbach 295 Stuttgart Baden-Baden Bad Wildbad 296 Sindelfingen Freiburg Calw 463 Böblingen 294 Herrenberg Tübingen Nagold 28 28 Freudenstadt Horb Reutlingen A81 Coming from Calmbach: In the centre of Calmbach change B 294 to B 296 in the direction Calw, drive through Oberreichenbach and 1 km outside the village turn left towards Klinikum Nordschwarzwald. Coming from Hirsau: Klinikum Nordschwarzwald Drive on the B 296 in the direction Oberreichenbach, after about 5 km branch off towards Klinikum Im Lützenhardter Hof Nordschwarzwald. 75365 Calw-Hirsau Tel.: 07051 586-0 Klinikum Fax.: 07051 586-2700 Calmbach Nordschwarzwald [email protected] Bad Liebenzell 296 www.kn-calw.de Oberkollbach 463 Bad Wildbad Hirsau Oberreichenbach Rechtsfähige Anstalt des öffentlichen Rechts Calw Geschäftsführer: Prof. Dr. Dr. Hans-Jürgen Seelos 294 463 Ein Unternehmen der ZfP-Gruppe Baden-Württemberg Orientation Plan Driving Directions . Sitemap 9 Paediatric psychiatry and Orientation Plan psychotherapy - station 60 10 Gymnasium 11 Playing fields 10 12 Residential area „Lützenhardter Hof“ 11 19 9 13 Nurse’s training school 8 20 14 Social counselling (house 16) 12 21 17 6 15 Ergotherapy, art therapy 7 16 H 13 18 P i 3 5 16 Work therapy “paper”, 15 14 art therapy, 4 car pool, trade workshops i i 2 17 Work therapy “textiles”/“metal”, i H kitchen, bakery 1 P -

B. Development of Supply Curves for Environmental Compensation

Proceedings of the 3rd INFER Symposium on Agri-Tech Economics for Sustainable Futures 21st – 22nd September 2020, Harper Adams University, Newport, United Kingdom. Compiled and edited by Karl Behrendt and Dimitrios Paparas Harper Adams University, Global Institute for Agri-Tech Economics, Land, Farm and Agribusiness Management Department Copyright 2020 by submitting Authors listed in papers. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. Development of supply curves for environmental compensation measures on farmland on the example of the Stuttgart Region in Germany Christian Sponagel, Hans Back, Elisabeth Angenendt and Enno Bahrs Institute of Farm Management, Stuttgart, Germany Abstract Impacts on nature and landscape in Germany must be compensated for in accordance with the Federal Nature Conservation Act. Farmers can participate by voluntarily applying appropriate measures on their land. We used a geodata-based model to analyse environmental compensation measures on arable land from an economic perspective on the example of the Stuttgart Region, a metropolitan area where construction activities and their compensation are huge, exemplary for many European metropolises. In order to estimate a possible realistic potential, the willingness to accept for compensation measures previously determined in a discrete choice experiment with farmers in the Stuttgart region was integrated into the model. The analysis compares the economic viability of current agricultural use with the income generated from the sale of so called ecopoints by supply curve. The results show wide variation in ecopoint potential in spatial terms. The implementation of compensation measures is not economically reasonable, depending on the legal security provided by a land register entry at a price of less than 1.00 € per ecopoint in the Stuttgart city district. -

Karte Der Erdbebenzonen Und Geologischen Untergrundklassen

Karte der Erdbebenzonen und geologischen Untergrundklassen 350 000 KARTE DER ERDBEBENZONEN UND GEOLOGISCHEN UNTERGRUNDKLASSEN FÜR BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG 1: für Baden-Württemberg 10° 1 : 350 000 9° BAYERN 8° HESSEN RHEINLAND- PFALZ WÜRZBUR G Die Karte der Erdbebenzonen und geologischen Untergrundklassen für Baden- Mainz- Groß- Main-Spessart g Wertheim n Württemberg bezieht sich auf DIN 4149:2005-04 "Bauten in deutschen Darmstadt- li Gerau m Bingen m Main Kitzingen – Lastannahmen, Bemessung und Ausführung üblicher Freudenberg Erdbebengebieten Mü Dieburg Ta Hochbauten", herausgegeben vom DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V.; ub Kitzingen EIN er Burggrafenstr. 6, 10787 Berlin. RH Alzey-Worms Miltenberg itz Die Erdbebenzonen beruhen auf der Berechnung der Erdbebengefährdung auf Weschn Odenwaldkreis Main dem Niveau einer Nicht-Überschreitenswahrscheinlichkeit von 90 % innerhalb Külsheim Werbach Großrinderfeld Erbach Würzburg von 50 Jahren für nachfolgend angegebene Intensitätswerte (EMS-Skala): Heppenheim Mud Pfrimm Bergst(Bergstraraßeß) e Miltenberg Gebiet außerhalb von Erdbebenzonen Donners- WORMS Tauberbischofsheim Königheim Grünsfeld Wittighausen Gebiet sehr geringer seismischer Gefährdung, in dem gemäß Laudenbach Hardheim des zugrunde gelegten Gefährdungsniveaus rechnerisch die bergkreis Höpfingen Hemsbach Main- Intensität 6 nicht erreicht wird Walldürn zu Golla Bad ch Aisch Lauda- Mergentheim Erdbebenzone 0 Weinheim Königshofen Neustadt Gebiet, in dem gemäß des zugrunde gelegten Gefährdungsniveaus Tauber-Kreis Mudau rechnerisch die Intensitäten 6 bis < 6,5 zu erwarten sind FRANKENTHAL Buchen (Odenwald) (Pfalz) Heddes-S a. d. Aisch- Erdbebenzone 1 heim Ahorn RHirschberg zu Igersheim Gebiet, in dem gemäß des zugrunde gelegten Gefährdungsniveaus an der Bergstraße Eberbach Bad MANNHEIM Heiligkreuz- S c Ilves- steinach heff Boxberg Mergentheim rechnerisch die Intensitäten 6,5 bis < 7 zu erwarten sind Ladenburg lenz heim Schriesheim Heddesbach Weikersheim Bad Windsheim LUDWIGSHAFEN Eberbach Creglingen Wilhelmsfeld Laxb Rosenberg Erdbebenzone 2 a. -

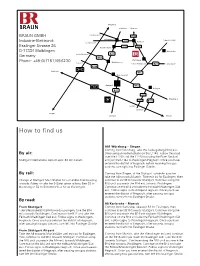

How to Find Us

Würzburg Heilbronn Marbach Ludwigsburg-Nord BRAUN GMBH L1100 Ludwigsburg Schwäbisch Hall L1140 Remseck Industrie-Elektronik Ludwigsburg-Süd L1144 L1142 Esslinger Strasse 26 Kornwestheim D-71334 Waiblingen Winnenden Korntal-Münchingen B27 Germany B10 Waiblingen Phone: +49 (0)7151/956230 Zuenhausen Weilimdorf Fellbach-Waiblingen Süd B29 Schorndorf B295 A81 Karlsruhe B14 Bad Cannstatt Stuttgart A8 B10 Esslingen B27 L1192 Göppingen L1202 B313 Esslingen Wendlingen Singen Tübingen Munich How to find us A81 Würzburg – Singen Coming from Würzburg, take the Ludwigsburg-Nord exit. By air: Drive across Friedrichstraße on the L1140. Follow this road over the L1100 and the L1140 (crossing the River Neckar) Stuttgart International Airport appr. 30 km distant. and join the L1142 to Waiblingen-Hegnach. Once you have entered the district of Hegnach, before reaching two gas stations, turn right into Esslinger Straße. By rail: Coming from Singen, at the Stuttgart autobahn junction take the A8 towards Munich. Take exit 54 for Esslingen, then Change at Stuttgart Main Station for a mainline train heading continue to exit B10 towards Stuttgart. Continue along the towards Aalen, or take the S-Bahn urban railway (line S3 to B10 until you reach the B14 exit towards Waiblingen. Backnang or S2 to Schorndorf) as far as Waiblingen. Continue on the B14 and take the Fellbach/Waiblingen Süd exit. Follow signs to Waiblingen-Hegnach. Once you have entered the district of Hegnach, after passing two gas stations, turn left into Esslinger Straße. By road: A8 Karlsruhe – Munich From Stuttgart Coming from Karlsruhe, take exit 54 for Esslingen, then Take Uferstraße/B10/B14 towards Esslingen, take the B14 continue to exit B10 towards Stuttgart.