Allan Shivers' East Texas Political Network, 1950

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

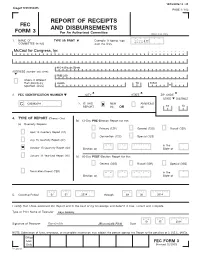

Report of Receipts and Disbursements

10/15/2014 12 : 23 Image# 14978252435 PAGE 1 / 162 REPORT OF RECEIPTS FEC AND DISBURSEMENTS FORM 3 For An Authorized Committee Office Use Only 1. NAME OF TYPE OR PRINT Example: If typing, type 12FE4M5 COMMITTEE (in full) over the lines. McCaul for Congress, Inc 815-A Brazos Street ADDRESS (number and street) PMB 230 Check if different than previously Austin TX 78701 reported. (ACC) 2. FEC IDENTIFICATION NUMBER CITY STATE ZIP CODE STATE DISTRICT C C00392688 3. IS THIS NEW AMENDED REPORT (N) OR (A) TX 10 4. TYPE OF REPORT (Choose One) (b) 12-Day PRE -Election Report for the: (a) Quarterly Reports: Primary (12P) General (12G) Runoff (12R) April 15 Quarterly Report (Q1) Convention (12C) Special (12S) July 15 Quarterly Report (Q2) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the October 15 Quarterly Report (Q3) Election on State of January 31 Year-End Report (YE) (c) 30-Day POST -Election Report for the: General (30G) Runoff (30R) Special (30S) Termination Report (TER) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the Election on State of M M / D D / Y Y Y Y M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 5. Covering Period 07 01 2014 through 09 30 2014 I certify that I have examined this Report and to the best of my knowledge and belief it is true, correct and complete. Type or Print Name of Treasurer Kaye Goolsby M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 10 15 2014 Signature of Treasurer Kaye Goolsby [Electronically Filed] Date NOTE: Submission of false, erroneous, or incomplete information may subject the person signing this Report to the penalties of 2 U.S.C. -

Of Judicial Independence Tara L

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 2 Article 3 2018 The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence Tara L. Grove Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Tara L. Grove, The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence, 71 Vanderbilt Law Review 465 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol71/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence Tara Leigh Grove* The federal judiciary today takes certain things for granted. Political actors will not attempt to remove Article II judges outside the impeachment process; they will not obstruct federal court orders; and they will not tinker with the Supreme Court's size in order to pack it with like-minded Justices. And yet a closer look reveals that these "self- evident truths" of judicial independence are neither self-evident nor necessary implications of our constitutional text, structure, and history. This Article demonstrates that many government officials once viewed these court-curbing measures as not only constitutionally permissible but also desirable (and politically viable) methods of "checking" the judiciary. The Article tells the story of how political actors came to treat each measure as "out of bounds" and thus built what the Article calls "conventions of judicial independence." But implicit in this story is a cautionary tale about the fragility of judicial independence. -

George I. Sanchez and the Civil Rights Movement: 1940-1960

George I. Sanchez and the Civil Rights Movement: 1940-1960 Ricardo Romo* This article is a tribute to Dr. George I. Sanchez and examines the important contributions he made in establishing the American Council of Spanish-Speaking People (ACSSP) in 1951. The ACSSP funded dozens of civil rights cases in the Southwest during the early 1950's and repre- sented the first large-scale effort by Mexican Americans to establish a national civil rights organization. As such, ACSSP was a precursor of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) and other organizations concerned with protecting the legal rights of Mexican Americans in the Southwest. The period covered here extends from 1940 to 1960, two crucial decades when Mexican Ameri- cans made a concerted effort to challenge segregation in public schools, discrimination in housing and employment, and the denial of equal ac- cess to public places such as theaters, restaurants, and barber shops. Although Mexican Americans are still confronted today by de facto seg- regation and job discrimination, it is of historical and legal interest that Mexican American legal victories, in areas such as school desegregation, predated by many years the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education and the civil rights movement of the 1960's. Sanchez' pioneering leadership and the activities of ACSSP merit exami- nation if we are to fully comprehend the historical struggle of the Mexi- can American civil rights movement. In a recent article, Karen O'Conner and Lee Epstein traced the ori- gins of MALDEF to the 1960's civil rights era.' The authors argued that "Chicanos early on recongized their inability to seek rights through traditional political avenues and thus sporadically resorted to litigation .. -

Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ____~____ ~:-:'----;-- - ~-- ----;--;:-'l~. - Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress ,. In 1967, the Department published a report, Texas Department of Corrections: 20 Years of Progress. That report was largely the work of Mr. Richard C. Jones, former Assistant Director for Treatment. The report that follows borrowed hea-vily and in many cases directly from Mr. Jones' efforts. This is but another example of how we continue to profit from, and, hopefully, build upon the excellent wC';-h of those preceding us. Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress NCJRS dAN 061978 ACQUISIT10i~:.j OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR DOLPH BRISCOE STATE CAPITOL GOVERNOR AUSTIN, TEXAS 78711 My Fellow Texans: All Texans owe a debt of gratitude to the Honorable H. H. Coffield. former Chairman of the Texas Board of Corrections, who recently retired after many years of dedicated service on the Board; to the present members of the Board; to Mr. W. J. Estelle, Jr., Director of the Texas Department of Corrections; and to the many people who work with him in the management of the Department. Continuing progress has been the benchmark of the Texas Department of Corrections over the past thirty years. Proposed reforms have come to fruition through the careful and diligent management p~ovided by successive administ~ations. The indust~ial and educational p~ograms that have been initiated have resulted in a substantial tax savings for the citizens of this state and one of the lowest recidivism rates in the nation. -

Principal State and Territorial Officers

/ 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Atlorneys .... State Governors Lieulenanl Governors General . Secretaries of State. Alabama. James E. Foisoin J.C.Inzer .A. .A.. Carniichael Sibyl Pool Arizona Dan E. Garvey None Fred O. Wilson Wesley Boiin . Arkansas. Sid McMath Nathan Gordon Ike Marry . C. G. Hall California...... Earl Warren Goodwin J. Knight • Fred N. Howser Frank M. Jordan Colorado........ Lee Knous Walter W. Jolinson John W. Metzger George J. Baker Connecticut... Chester Bowles Wm. T. Carroll William L. Hadden Mrs. Winifred McDonald Delaware...:.. Elbert N. Carvel A. duPont Bayard .Mbert W. James Harris B. McDowell, Jr. Florida.. Fuller Warren None Richard W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia Herman Talmadge Marvin Griffin Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. * Idaho ;C. A. Robins D. S. Whitehead Robert E. Sniylie J.D.Price IlUnola. .-\dlai E. Stevenson Sher^vood Dixon Ivan.A. Elliott Edward J. Barrett Indiana Henry F. Schricker John A. Walkins J. Etnmett McManamon Charles F. Fleiiiing Iowa Wm. S.'Beardsley K.A.Evans Robert L. Larson Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas Frank Carlson Frank L. Hagainan Harold R. Fatzer (a) Larry Ryan Kentucky Earle C. Clements Lawrence Wetherby A. E. Funk • George Glenn Hatcher Louisiana Earl K. Long William J. Dodd Bolivar E. Kemp Wade O. Martin. Jr. Maine.. Frederick G. Pgynp None Ralph W. Farris Harold I. Goss Maryland...... Wm. Preston Lane, Jr. None Hall Hammond Vivian V. Simpson Massachusetts. Paul A. Dever C. F. Jeff Sullivan Francis E. Kelly Edward J. Croiiin Michigan G. Mennen Williams John W. Connolly Stephen J. Roth F. M. Alger, Jr.- Minnesota. -

Name Abbreviations for Nixon White House Tapes

-1- NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM Name Abbreviations List (rev. January-2013) ACC Anna C. Chennault ACD Arthur C. Deck A ACf Ann Coffin AA Alexander Akalovsky ACH Allen C. Hall AAD* Mrs. and Mrs. Albert A. ACN Arnold C. Noel Doub ACt Americo Cortese AAF Arthur A. Fletcher AD Andrew Driggs AAG Andrei A. Gromyko ADahl Arlene Dahl AAhmed Aziz Ahmed ADavis Alan Davis AAL Gen. Alejandro A. Lanusse ADM Anthony D. Marshall AAM Arch A. Moore ADn Alan Dean AANH Abdel Aziz Nazri Hamza ADN Antonio D. Neto AAR Abraham A. Ribicoff Adoub Albert Doub AAS Arthur A. Shenfield ADR Angelo D. Roncallo AAW A. A. Wood ADram Adriana Dramesi AB Ann Broomell ADRudd Alice D. Rudd ABakshian Aram Bakshian, Jr. ADS* Mr. and Mrs. Alex D. ABC Anna B. Condon Steinkamp ABCh Alton B. Chamberlain ADuggan Ann Duggan ABH A. Blaine Huntsman ADv Ann Davis ABible Alan Bible AE Alan Emory Abll Alan Bell AED Arthur E. Dewey ABog Mr. and Mrs. Archie Boggs AEG Andrew E. Gibson ABw Ann Brewer AEH Albert E. Hole AC Arthene Cevey AEN Anna Edwards Hensgens ACag Andrea Cagiatti AEO'K Alvin E. O'Kinski ACameron Alan Cameron AES Arthur E. Summerfield ACBFC Anne C.B. (Finch) Cox AESi Albert E. Sindlinger -2- NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM Name Abbreviations List (rev. January-2013) AF Arthur Fagan AHS Arthur H. Singer AFB Arthur F. Burns AIS Armistead I. Selden, Jr. AFBr Andrew F. Brimmer AJ Andrew Jackson AFD Anatoliy F. Dobrynin AJaffe Ari Jaffe AFD-H Sir Alexander F. Douglas- AJB A.J. -

A Historical Perspective of the Permeable IRS Prohibition on Campaigning by Churches Patrick L

Boston College Law Review Volume 42 Issue 4 The Conflicted First Amendment: Tax Article 1 Exemptions, Religious Groups, And Political Activity 7-1-2001 More Honored in the Breach: A Historical Perspective of the Permeable IRS Prohibition on Campaigning by Churches Patrick L. O'Daniel Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Religion Law Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Recommended Citation Patrick L. O'Daniel, More Honored in the Breach: A Historical Perspective of the Permeable IRS Prohibition on Campaigning by Churches, 42 B.C.L. Rev. 733 (2001), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol42/iss4/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MORE HONORED IN THE BREACH: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF THE PERMEABLE IRS PROHIBITION ON CAMPAIGNING BY CHURCHES PATRICK L. O'DANIEL* Abstract: Since 1954, there has been a prohibition on certain forms of intervention in political campaigns by entities exempt frOm taxation under section 501(c) (3) of the Internal Revenue Code—including most. churches. This Article provides a historical perspective on the genesis of this prohibition—the 1954 U.S. Senate campaign of its sponsor, Lyndon Baines Johnson, and the involvement of religious entities and other 501 (c) (3) organizations in his political campaign. Although Johnson was not opposed to using churches to advance his own political interests, lie (lid seek to prevent ideological, tax-exempt organizations from funding McCarthyite candidates including his opponent in the Democratic primary, Dudley Dougherty. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 106 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 145 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, MAY 4, 1999 No. 63 House of Representatives The House met at 12:30 p.m. tainted water supply cleaned up, the into effect, and they still will not f guilty must be found, and they must be admit, is that MTBE is a powerful and punished. persistent water pollutant and, from MORNING HOUR DEBATES Now this perhaps sounds like a Holly- leaks and spills, has made its way into The SPEAKER. Pursuant to the wood plot, a Hollywood movie, but it is groundwater of nearly every State in order of the House of January 19, 1999, not, and for many communities across this Nation; the problem, of course, the Chair will now recognize Members this Nation, they are facing this situa- being worse in California, the har- from lists submitted by the majority tion. The guilty party is none other binger of what will surely come to pass and minority leaders for morning hour than the supposed protector, the Envi- in much of the rest of this country. It debates. The Chair will alternate rec- ronmental Protection Agency. takes only a small amount of MTBE to ognition between the parties, with each Tom Randall, a managing editor of make water undrinkable. It spreads party limited to 30 minutes, and each the Environmental News, recently rapidly in both groundwater and res- Member, except the majority leader, brought some articles to my attention. -

Arxas Obstrurr We See It

The one great rule TV e will serve MP of composition is to group or party but will hew hard to speak the truth. the truth as we find it and the right as -Thoreau arxas Obstrurr we see it. An Independent Liberal Weekly Newspaper Vol. 47 TEXAS, MARCH 7, 1956 10c per copy No. 46 sponses received through March 12 will be published March 14. 'ADM!, RALPH D.A.C. LEADERS The tabulations : AUSTIN Poll of Loyalist Group Shows Hart, White Nos. FOR PRESIDENT Loyalist Democratic leaders i n 2, 3 :Texas prefer Adlai Stevenson for First Second Third In Governor's Race; Kefauver Second to Stevenson Choice Choice Choice president and Ralph Yarborough for No. Pct. No. Pct. No. Pct. governor, their replies to an Observer ough with no second and third • place Stevenson .... 56 .78 9 '.13 4 .06 third place vote ; and W. (40 Cooper Kefauver 7 .10 24 .33 15 .21 poll indicate. choices, commented : "There is •only of Dallas was written in with a strong Harriman 2 .03 20 .28 23 .32 As of Monday afternoon, 72 of 141 one candidate." Another remarked: recommendation, but without a spe- Others* 5 .07 4 .06 4 .06 "Yarborough first, second, or third- cific vote. members of the Democratic Advisory TOTALS ... 70 .97* 57 .79* 46 . .64 Council had responded to the Observ- no other." In the presidential voting, Senator er's postcard query. Principal surprise in the results is Symington received three s first-place FOR GOVERNOR The Observer .asked for first, sec- the strengthening of Hart's standing votes and one each for second and First Second Third ond, and third preferences in both among liberal-loyalist leaders. -

HON. OVERTON BROOKS Successively Reduced to Exhaustion

1956 tONGRESSiONAL . RECORD - HOUSE 9441 tigate and study tariff.. and _ttade ·1awa; Tegil'• - - . BY. Mr. 'MARON: enactment of a-sepal'ate ·.and liberal ·pensfon Lations, practices, and ~licies, with_reference H. R. 11587. A bill for the relief of Shakeeb program for veterans of World War I and to their effect on industry, labor, and agri Dakour; to the Committee on the Judiciary. their widows and orphans; to the Committee culture ln · the Unlted St!ltes; to the Cam ' By Mr. PELLY: . <>n Veterans' Affairs. mi ttee on Rules. · · J - H. R. 11588. A bill for the ·relief of Mrs. ·. 1099. By Mr. SILER: Petition of Dr. David . By Mr. HIESTAND~ . ·Norberta Cueto~ to the Committee on the A. Cavin, president, Baptist Bible Fellow H. Res. 523. Resolution creating a select JudiCiary. · ~ ship, Springfield, Mo., and Jesse M. Seaver, committee to conduct an investigation and By Mr. RADWAN: <iirector, Carolina Christian Union, Roanoke ~study of labor racketeering in the United H. R. 11589. A bill for the relief of O. J. Rapids, N. C., on behalf of some 1,800 dele States; to the Committ-e~ on ~Ule's. Glenn & Son, Inc.; to the Committee on the gates and members of the Baptist Bible Fel ~udiciary. ' lowship at their annual national meeting at By Mr. ROGERS of Colorado: Springfield, Mo., urging enactment of the PRIVATE ·BILLS AND 'R'ESOLUTIONS · H. R. 11590. A bill for the relief of Harry?'(. ·Siler bill, H. R. 4627, and .the Langer bill!, _ Under clause.1 ~of rule rill, privat~ ~Duff; to the Committee on the Judiciary. -

Fight for the Right: the Quest for Republican Identity in the Postwar Period

FIGHT FOR THE RIGHT: THE QUEST FOR REPUBLICAN IDENTITY IN THE POSTWAR PERIOD By MICHAEL D. BOWEN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 Copyright 2006 by Michael D. Bowen ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project is the culmination of many years of hard work and dedication, but it would not have been possible without assistance and support from a number of individuals along the way. First and foremost, I have to thank God and my parents for all that they have done for me since before I arrived at the University of Florida. Dr. Brian Ward, whose admiration for West Ham United is only surpassed by his love for the band Gov’t Mule, was everything I could have asked for in an advisor. Dr. Charles Montgomery pushed and prodded me to turn this project from a narrow study of the GOP to a work that advances our understanding of postwar America. Dr. Robert Zieger was a judicious editor whose suggestions greatly improved my writing at every step of the way. Drs. George Esenwein and Daniel Smith gave very helpful criticism in the later stages of the project and helped make the dissertation more accessible. I would also like to thank my fellow graduate students in the Department of History, especially the rest of “Brian Ward’s Claret and Blue Army,” for helping make the basement of Keene-Flint into a collegial place and improving my scholarship through debate and discussion. -

Arxtts Obstrurr We See It

We will serve so The one great rule group or party but of composition is to will hew hard to the truth as we find speak the truth'. it and the right as —Thorea, arxtts Obstrurr we see it. - An Independent Liberal Weekly Newspaper vol. 47 TEXAS, DECEMBER 28, 1955 10c per copy No. 34 Dallas Solon's Firm Paid $30,000 Irwin Charges 'Persecution' Of His Company Insurance Speculator Paid Back Fee Lately; Cain Says 'Knows' Officials DALLAS JoeWin, is fighting to save his American Atlas. He is fighting scared, and he is fighting hard. For three hours - last week in his company offices here, he spelled out to the Ob- server a story of his own financial' outwitting- and of his relationship with the Texas Insurance Commis- sion. He said he paid the law firm of which State Representative Douglas Insurance Commission officials in "born in sin." Commissioners found —Staff Photos Bergman is an active member a total company . insolvent June 24 but of about $30,000 in fees this year. district courtroom last week in Aus- tin heard a day's testimony cli- took no action to close it down. Left Smith, chairman of the commission; He said that thirteen or fourteen to right, Mark Wentz, commis- J. Byron Saunders, commissioner. thousand of this was "a back fee" maxed when Judge Charles Betts called U.S. Trust & Guaranty Co. sioner ; Joe Moore, head, securities The commissioners were appointed paid to Bergman's firm to help get division of the commission; Garland of Gov. Shivers. three of his minor companies "quietly "most amazing," "fraudulent," and buried by the Insurance Commission" to protect-his stockholders in Ameri- can Atlas Corporation.