Of Judicial Independence Tara L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

By Patrick James Barry a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The

CONFIRMATION BIAS: STAGED STORYTELLING IN SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARINGS by Patrick James Barry A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English Language and Literature) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Enoch Brater, Chair Associate Professor Martha Jones Professor Sidonie Smith Emeritus Professor James Boyd White TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 SITES OF THEATRICALITY 1 CHAPTER 2 SITES OF STORYTELLING 32 CHAPTER 3 THE TAUNTING OF AMERICA: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF ROBERT BORK 55 CHAPTER 4 POISON IN THE EAR: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF CLARENCE THOMAS 82 CHAPTER 5 THE WISE LATINA: THE SUPREME COURT CONFIRMATION HEARING OF SONIA SOTOMAYOR 112 CHAPTER 6 CONCLUSION: CONFIRMATION CRITIQUE 141 WORK CITED 166 ii CHAPTER 1 SITES OF THEATRICALITY The theater is a place where a nation thinks in public in front of itself. --Martin Esslin, An Anatomy of Drama (1977)1 The Supreme Court confirmation process—once a largely behind-the-scenes affair—has lately moved front-and-center onto the public stage. --Laurence Tribe, Advice and Consent (1992)2 I. In 1975 Milner Ball, then a law professor at the University of Georgia, published an article in the Stanford Law Review called “The Play’s the Thing: An Unscientific Reflection on Trials Under the Rubric of Theater.” In it, Ball argued that by looking at the actions that take place in a courtroom as a “type of theater,” we might better understand the nature of these actions and “thereby make a small contribution to an understanding of the role of law in our society.”3 At the time, Ball’s view that courtroom action had an important “theatrical quality”4 was a minority position, even a 1 Esslin, Martin. -

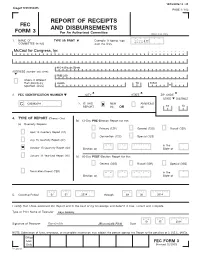

Report of Receipts and Disbursements

10/15/2014 12 : 23 Image# 14978252435 PAGE 1 / 162 REPORT OF RECEIPTS FEC AND DISBURSEMENTS FORM 3 For An Authorized Committee Office Use Only 1. NAME OF TYPE OR PRINT Example: If typing, type 12FE4M5 COMMITTEE (in full) over the lines. McCaul for Congress, Inc 815-A Brazos Street ADDRESS (number and street) PMB 230 Check if different than previously Austin TX 78701 reported. (ACC) 2. FEC IDENTIFICATION NUMBER CITY STATE ZIP CODE STATE DISTRICT C C00392688 3. IS THIS NEW AMENDED REPORT (N) OR (A) TX 10 4. TYPE OF REPORT (Choose One) (b) 12-Day PRE -Election Report for the: (a) Quarterly Reports: Primary (12P) General (12G) Runoff (12R) April 15 Quarterly Report (Q1) Convention (12C) Special (12S) July 15 Quarterly Report (Q2) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the October 15 Quarterly Report (Q3) Election on State of January 31 Year-End Report (YE) (c) 30-Day POST -Election Report for the: General (30G) Runoff (30R) Special (30S) Termination Report (TER) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the Election on State of M M / D D / Y Y Y Y M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 5. Covering Period 07 01 2014 through 09 30 2014 I certify that I have examined this Report and to the best of my knowledge and belief it is true, correct and complete. Type or Print Name of Treasurer Kaye Goolsby M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 10 15 2014 Signature of Treasurer Kaye Goolsby [Electronically Filed] Date NOTE: Submission of false, erroneous, or incomplete information may subject the person signing this Report to the penalties of 2 U.S.C. -

The Honorable Hubert H. Humphrey United States Senate Washington, D

I The University of Chicago Chicago 37, Illinois August 2, 1955 The Honorable Hubert H. Humphrey United States Senate Washington, D. C. Dear Senator Humphrey: You asked me what function I thought the Subcommittee on Dis armament of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee might fulfill in the short period of time and with the limited means available between now and the first of January, and you suggested that I put my thoughts on paper. The main issue as far as substance is concerned, it seems to me, can be phrased as follows: 11 What kind and what degree of disarmament is desirable within the framework of what political settlement?" It seems to me that one would only add to the already existing confusion if disarma ment were discussed without stating clearly what is being assumed concern ing the political settlement within which it would have to operate. I assume that few Senators will be available between the im pending adjournment of Congress and the first of January, and thusthe ques tion is what could be accomplished by a competent staff. I believe such a staff could hold conferences of the fol_lowing sort: Men like Walter Lippman, George Kennan, and perhaps five to ten others who in the past have written on one aspect of the problem or another, would be asked to prepare their thoughts on the "whole problem" and to tell to a critical audience, assembled by the staff, what they would regard as a desirable settlement. They must imagine that somehow they are endowed with such magical power of persuasion that they could convince the -

U.S. President's Committee for Hungarian Refugee Relief

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. PRESIDENT’S COMMITTEE FOR HUNGARIAN REFUGEE RELIEF: Records, 1957 A67-4 Compiled by Roland W. Doty, Jr. William G. Lewis Robert J. Smith 16 cubic feet 1956-1957 September 1967 INTRODUCTION The President’s Committee for Hungarian Refugee Relief was established by the President on December 12, 1956. The need for such a committee came about as a result of the United States’ desire to take care of its fair share of the Hungarians who fled their country beginning in October 1956. The Committee operated until May, 1957. During this time, it helped re-settle in the United States approximately 30,000 refugees. The Committee’s small staff was funded from the Special Projects Group appropriation. In its creation, the Committee was assigned the following duties and objectives: a. To assist in every way possible the various religious and other voluntary agencies engaged in work for Hungarian Refugees. b. To coordinate the efforts of these agencies, with special emphasis on those activities related to resettlement of the refugees. The Committee also served as a focal point to which offers of homes and jobs could be forwarded. c. To coordinate the efforts of the voluntary agencies with the work of the interested governmental departments. d. It was not the responsibility of the Committee to raise money. The records of the President’s Committee consists of incoming and outgoing correspondence, press releases, speeches, printed materials, memoranda, telegrams, programs, itineraries, statistical materials, air and sea boarding manifests, and progress reports. The subject areas of these documents deal primarily with requests from the public to assist the refugees and the Committee by volunteering homes, employment, adoption of orphans, and even marriage. -

George I. Sanchez and the Civil Rights Movement: 1940-1960

George I. Sanchez and the Civil Rights Movement: 1940-1960 Ricardo Romo* This article is a tribute to Dr. George I. Sanchez and examines the important contributions he made in establishing the American Council of Spanish-Speaking People (ACSSP) in 1951. The ACSSP funded dozens of civil rights cases in the Southwest during the early 1950's and repre- sented the first large-scale effort by Mexican Americans to establish a national civil rights organization. As such, ACSSP was a precursor of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) and other organizations concerned with protecting the legal rights of Mexican Americans in the Southwest. The period covered here extends from 1940 to 1960, two crucial decades when Mexican Ameri- cans made a concerted effort to challenge segregation in public schools, discrimination in housing and employment, and the denial of equal ac- cess to public places such as theaters, restaurants, and barber shops. Although Mexican Americans are still confronted today by de facto seg- regation and job discrimination, it is of historical and legal interest that Mexican American legal victories, in areas such as school desegregation, predated by many years the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education and the civil rights movement of the 1960's. Sanchez' pioneering leadership and the activities of ACSSP merit exami- nation if we are to fully comprehend the historical struggle of the Mexi- can American civil rights movement. In a recent article, Karen O'Conner and Lee Epstein traced the ori- gins of MALDEF to the 1960's civil rights era.' The authors argued that "Chicanos early on recongized their inability to seek rights through traditional political avenues and thus sporadically resorted to litigation .. -

Crime, 1966-1967

The original documents are located in Box D6, folder “Ford Press Releases - Crime, 1966- 1967 (2)” of the Ford Congressional Papers: Press Secretary and Speech File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. The Council donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box D6 of the Ford Congressional Papers: Press Secretary and Speech File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library CONGRESSMAN NEWS GERALD R. FORD HOUSE REPUBLICAN LEADER RELEASE ••Release in PMs of August 3-- Remarks by Rep. Gerald R. Ford, R-Mich., prepared for delivery on the floor of the House on Thursday, August 3, 1967. Mr. Speaker, America today is shaken by a deep national crisis--a near- breakdown of law and order made even more severe by civil disorders in which criminal elements are heavily engaged. The law-abiding citizens of America who have suffered at the hands of the lawless and the extremists are anxiously awaiting a remedy. This is a time for swift and decisive acti~n. -

The Senate in Transition Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Nuclear Option1

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NYL\19-4\NYL402.txt unknown Seq: 1 3-JAN-17 6:55 THE SENATE IN TRANSITION OR HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE NUCLEAR OPTION1 William G. Dauster* The right of United States Senators to debate without limit—and thus to filibuster—has characterized much of the Senate’s history. The Reid Pre- cedent, Majority Leader Harry Reid’s November 21, 2013, change to a sim- ple majority to confirm nominations—sometimes called the “nuclear option”—dramatically altered that right. This article considers the Senate’s right to debate, Senators’ increasing abuse of the filibuster, how Senator Reid executed his change, and possible expansions of the Reid Precedent. INTRODUCTION .............................................. 632 R I. THE NATURE OF THE SENATE ........................ 633 R II. THE FOUNDERS’ SENATE ............................. 637 R III. THE CLOTURE RULE ................................. 639 R IV. FILIBUSTER ABUSE .................................. 641 R V. THE REID PRECEDENT ............................... 645 R VI. CHANGING PROCEDURE THROUGH PRECEDENT ......... 649 R VII. THE CONSTITUTIONAL OPTION ........................ 656 R VIII. POSSIBLE REACTIONS TO THE REID PRECEDENT ........ 658 R A. Republican Reaction ............................ 659 R B. Legislation ...................................... 661 R C. Supreme Court Nominations ..................... 670 R D. Discharging Committees of Nominations ......... 672 R E. Overruling Home-State Senators ................. 674 R F. Overruling the Minority Leader .................. 677 R G. Time To Debate ................................ 680 R CONCLUSION................................................ 680 R * Former Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy for U.S. Senate Democratic Leader Harry Reid. The author has worked on U.S. Senate and White House staffs since 1986, including as Staff Director or Deputy Staff Director for the Committees on the Budget, Labor and Human Resources, and Finance. -

Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ____~____ ~:-:'----;-- - ~-- ----;--;:-'l~. - Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress ,. In 1967, the Department published a report, Texas Department of Corrections: 20 Years of Progress. That report was largely the work of Mr. Richard C. Jones, former Assistant Director for Treatment. The report that follows borrowed hea-vily and in many cases directly from Mr. Jones' efforts. This is but another example of how we continue to profit from, and, hopefully, build upon the excellent wC';-h of those preceding us. Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress NCJRS dAN 061978 ACQUISIT10i~:.j OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR DOLPH BRISCOE STATE CAPITOL GOVERNOR AUSTIN, TEXAS 78711 My Fellow Texans: All Texans owe a debt of gratitude to the Honorable H. H. Coffield. former Chairman of the Texas Board of Corrections, who recently retired after many years of dedicated service on the Board; to the present members of the Board; to Mr. W. J. Estelle, Jr., Director of the Texas Department of Corrections; and to the many people who work with him in the management of the Department. Continuing progress has been the benchmark of the Texas Department of Corrections over the past thirty years. Proposed reforms have come to fruition through the careful and diligent management p~ovided by successive administ~ations. The indust~ial and educational p~ograms that have been initiated have resulted in a substantial tax savings for the citizens of this state and one of the lowest recidivism rates in the nation. -

30Th Anniversary “Pearl” Award

Press release from the office of Maryland Governor Marin O’Malley Keith Campbell, Chairman of the Keith Campbell Foundation for the Environment received a special 30th Anniversary "Pearl" Award ANNAPOLIS, MD (October 19, 2009) –The Maryland League of Conservation Voters (LCV) honored Senator Barbara Mikulski with its annual John V. Kabler Memorial Award in recognition of her many achievements in protecting Maryland’s Land, Air and Water. The award recognizes outstanding environmental leadership and commitment. The environmental organization known for its annual legislative report cards also gave a special 30th Anniversary “Pearl” Award to Keith Campbell, Chairman of the Keith Campbell Foundation for the Environment, for his efforts to restore the Chesapeake Bay and combat global warming. Senator Barbara A. Mikulski, four term U.S. Senator has a thirty-five year record of public service in Maryland. She is a dedicated public servant who from her earliest days in the spotlight understood what was “Smart Growth” and what was not— long before anyone had ever heard the term. As a member of the powerful Appropriations Committee, she fights every year for federal funding for environmental programs, especially the Chesapeake Bay Program, the Clean Water State Revolving Fund, and the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund. A trailblazer in drawing attention to the effects of global warming on the Bay, Mikulski funds 85% of the nation’s climate change-related science as Chairwoman of Commerce, Justice, Science Appropriations Subcommittee. Her stalwart defense of the environment in Maryland is embodied in her support for building a green jobs workforce, protecting the Chesapeake Bay, and for a clean energy economy. -

SENATE Back in His Accustomed Seat, and We Wish Thomas H

<ronyrrssional Rrcor~ United States PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 84th CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION of America happy to see the Senator from Texas California.-William F. Knowland and SENATE back in his accustomed seat, and we wish Thomas H. Kuchel. for him in the years ahead good health Colorado.-Eugene D. Millikin and TUESDAY, JANUARY 3, 1956 and happiness. [Applause.] Gordon Allott. The 3d day of January being the day Mr. JOHNSON of Texas. Mr. Presi Connecticut.-Prescott Bush and Wil prescribed by the Constitution of the dent, I appreciate very much the state liam A. Purtell. United States for the annual meeting ment the Vice President has just made ' Delaware.-John J. Williams and J. of Congress, the 2d session of the 84th about me. No one can know how glad I Allen Frear, Jr. Congress commenced this day. am again to be able to stand by this Florida.-Spessard L. Holland and The Senate assembled in its Cham desk, in the company of my treasured George A. Smathers. ber at the Capitol. friends on both sides of the aisle. I am Georgia.-Walter F. George and Rich RICHARD M. NIXON, of California, grateful to all of them for their under ard B. Russell. Vice President of the United States, standing, their patience, and the affec Idaho.-Henry C. Dworshak and Her called the Senate to order .at 12 o'clock tion which they expressed during the man Welker. meridian. dark days through which I have jour Illinois.-Paul H. Douglas and Everett The Chaplain, Rev. Frederick Brown neyed. M. -

Principal State and Territorial Officers

/ 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Atlorneys .... State Governors Lieulenanl Governors General . Secretaries of State. Alabama. James E. Foisoin J.C.Inzer .A. .A.. Carniichael Sibyl Pool Arizona Dan E. Garvey None Fred O. Wilson Wesley Boiin . Arkansas. Sid McMath Nathan Gordon Ike Marry . C. G. Hall California...... Earl Warren Goodwin J. Knight • Fred N. Howser Frank M. Jordan Colorado........ Lee Knous Walter W. Jolinson John W. Metzger George J. Baker Connecticut... Chester Bowles Wm. T. Carroll William L. Hadden Mrs. Winifred McDonald Delaware...:.. Elbert N. Carvel A. duPont Bayard .Mbert W. James Harris B. McDowell, Jr. Florida.. Fuller Warren None Richard W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia Herman Talmadge Marvin Griffin Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. * Idaho ;C. A. Robins D. S. Whitehead Robert E. Sniylie J.D.Price IlUnola. .-\dlai E. Stevenson Sher^vood Dixon Ivan.A. Elliott Edward J. Barrett Indiana Henry F. Schricker John A. Walkins J. Etnmett McManamon Charles F. Fleiiiing Iowa Wm. S.'Beardsley K.A.Evans Robert L. Larson Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas Frank Carlson Frank L. Hagainan Harold R. Fatzer (a) Larry Ryan Kentucky Earle C. Clements Lawrence Wetherby A. E. Funk • George Glenn Hatcher Louisiana Earl K. Long William J. Dodd Bolivar E. Kemp Wade O. Martin. Jr. Maine.. Frederick G. Pgynp None Ralph W. Farris Harold I. Goss Maryland...... Wm. Preston Lane, Jr. None Hall Hammond Vivian V. Simpson Massachusetts. Paul A. Dever C. F. Jeff Sullivan Francis E. Kelly Edward J. Croiiin Michigan G. Mennen Williams John W. Connolly Stephen J. Roth F. M. Alger, Jr.- Minnesota. -

Name Abbreviations for Nixon White House Tapes

-1- NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM Name Abbreviations List (rev. January-2013) ACC Anna C. Chennault ACD Arthur C. Deck A ACf Ann Coffin AA Alexander Akalovsky ACH Allen C. Hall AAD* Mrs. and Mrs. Albert A. ACN Arnold C. Noel Doub ACt Americo Cortese AAF Arthur A. Fletcher AD Andrew Driggs AAG Andrei A. Gromyko ADahl Arlene Dahl AAhmed Aziz Ahmed ADavis Alan Davis AAL Gen. Alejandro A. Lanusse ADM Anthony D. Marshall AAM Arch A. Moore ADn Alan Dean AANH Abdel Aziz Nazri Hamza ADN Antonio D. Neto AAR Abraham A. Ribicoff Adoub Albert Doub AAS Arthur A. Shenfield ADR Angelo D. Roncallo AAW A. A. Wood ADram Adriana Dramesi AB Ann Broomell ADRudd Alice D. Rudd ABakshian Aram Bakshian, Jr. ADS* Mr. and Mrs. Alex D. ABC Anna B. Condon Steinkamp ABCh Alton B. Chamberlain ADuggan Ann Duggan ABH A. Blaine Huntsman ADv Ann Davis ABible Alan Bible AE Alan Emory Abll Alan Bell AED Arthur E. Dewey ABog Mr. and Mrs. Archie Boggs AEG Andrew E. Gibson ABw Ann Brewer AEH Albert E. Hole AC Arthene Cevey AEN Anna Edwards Hensgens ACag Andrea Cagiatti AEO'K Alvin E. O'Kinski ACameron Alan Cameron AES Arthur E. Summerfield ACBFC Anne C.B. (Finch) Cox AESi Albert E. Sindlinger -2- NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY AND MUSEUM Name Abbreviations List (rev. January-2013) AF Arthur Fagan AHS Arthur H. Singer AFB Arthur F. Burns AIS Armistead I. Selden, Jr. AFBr Andrew F. Brimmer AJ Andrew Jackson AFD Anatoliy F. Dobrynin AJaffe Ari Jaffe AFD-H Sir Alexander F. Douglas- AJB A.J.