President Harry S Truman's Office Files, 1945–1953

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 30 2018 Seminole Tribune

BC cattle steer into Brooke Simpson relives time Heritage’s Stubbs sisters the past on “The Voice” win state title COMMUNITY v 7A Arts & Entertainment v 4B SPORTS v 1C Volume XLII • Number 3 March 30, 2018 National Folk Museum 7,000-year-old of Korea researches burial site found Seminole dolls in Manasota Key BY LI COHEN Duggins said. Copy Editor Paul Backhouse, director of the Ah-Tah- Thi-Ki Museum, found out about the site about six months ago. He said that nobody BY LI COHEN About two years ago, a diver looking for Copy Editor expected such historical artifacts to turn up in shark teeth bit off a little more than he could the Gulf of Mexico and he, along with many chew in Manasota Key. About a quarter-mile others, were surprised by the discovery. HOLLYWOOD — An honored Native off the key, local diver Joshua Frank found a “We have not had a situation where American tradition is moving beyond the human jaw. there’s organic material present in underwater horizon of the U.S. On March 14, a team of After eventually realizing that he had context in the Gulf of Mexico,” Backhouse researchers from the National Folk Museum a skeletal centerpiece sitting on his kitchen said. “Having 7,000-year-old organic material of Korea visited the Hollywood Reservation table, Frank notified the Florida Bureau of surviving in salt water is very surprising and to learn about the history and culture Archaeological Research. From analyzing that surprise turned to concern because our surrounding Seminole dolls. -

Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace In

TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2008 Major Subject: History TRUMAN, CONGRESS AND THE STRUGGLE FOR WAR AND PEACE IN KOREA A Dissertation by LARRY WAYNE BLOMSTEDT Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Terry H. Anderson Committee Members, Jon R. Bond H. W. Brands John H. Lenihan David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2008 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT Truman, Congress and the Struggle for War and Peace in Korea. (May 2008) Larry Wayne Blomstedt, B.S., Texas State University; M.S., Texas A&M University-Kingsville Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Terry H. Anderson This dissertation analyzes the roles of the Harry Truman administration and Congress in directing American policy regarding the Korean conflict. Using evidence from primary sources such as Truman’s presidential papers, communications of White House staffers, and correspondence from State Department operatives and key congressional figures, this study suggests that the legislative branch had an important role in Korean policy. Congress sometimes affected the war by what it did and, at other times, by what it did not do. Several themes are addressed in this project. One is how Truman and the congressional Democrats failed each other during the war. The president did not dedicate adequate attention to congressional relations early in his term, and was slow to react to charges of corruption within his administration, weakening his party politically. -

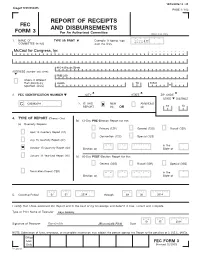

Report of Receipts and Disbursements

10/15/2014 12 : 23 Image# 14978252435 PAGE 1 / 162 REPORT OF RECEIPTS FEC AND DISBURSEMENTS FORM 3 For An Authorized Committee Office Use Only 1. NAME OF TYPE OR PRINT Example: If typing, type 12FE4M5 COMMITTEE (in full) over the lines. McCaul for Congress, Inc 815-A Brazos Street ADDRESS (number and street) PMB 230 Check if different than previously Austin TX 78701 reported. (ACC) 2. FEC IDENTIFICATION NUMBER CITY STATE ZIP CODE STATE DISTRICT C C00392688 3. IS THIS NEW AMENDED REPORT (N) OR (A) TX 10 4. TYPE OF REPORT (Choose One) (b) 12-Day PRE -Election Report for the: (a) Quarterly Reports: Primary (12P) General (12G) Runoff (12R) April 15 Quarterly Report (Q1) Convention (12C) Special (12S) July 15 Quarterly Report (Q2) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the October 15 Quarterly Report (Q3) Election on State of January 31 Year-End Report (YE) (c) 30-Day POST -Election Report for the: General (30G) Runoff (30R) Special (30S) Termination Report (TER) M M / D D / Y Y Y Y in the Election on State of M M / D D / Y Y Y Y M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 5. Covering Period 07 01 2014 through 09 30 2014 I certify that I have examined this Report and to the best of my knowledge and belief it is true, correct and complete. Type or Print Name of Treasurer Kaye Goolsby M M / D D / Y Y Y Y 10 15 2014 Signature of Treasurer Kaye Goolsby [Electronically Filed] Date NOTE: Submission of false, erroneous, or incomplete information may subject the person signing this Report to the penalties of 2 U.S.C. -

Of Judicial Independence Tara L

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 71 | Issue 2 Article 3 2018 The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence Tara L. Grove Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Tara L. Grove, The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence, 71 Vanderbilt Law Review 465 (2019) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol71/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Origins (and Fragility) of Judicial Independence Tara Leigh Grove* The federal judiciary today takes certain things for granted. Political actors will not attempt to remove Article II judges outside the impeachment process; they will not obstruct federal court orders; and they will not tinker with the Supreme Court's size in order to pack it with like-minded Justices. And yet a closer look reveals that these "self- evident truths" of judicial independence are neither self-evident nor necessary implications of our constitutional text, structure, and history. This Article demonstrates that many government officials once viewed these court-curbing measures as not only constitutionally permissible but also desirable (and politically viable) methods of "checking" the judiciary. The Article tells the story of how political actors came to treat each measure as "out of bounds" and thus built what the Article calls "conventions of judicial independence." But implicit in this story is a cautionary tale about the fragility of judicial independence. -

George I. Sanchez and the Civil Rights Movement: 1940-1960

George I. Sanchez and the Civil Rights Movement: 1940-1960 Ricardo Romo* This article is a tribute to Dr. George I. Sanchez and examines the important contributions he made in establishing the American Council of Spanish-Speaking People (ACSSP) in 1951. The ACSSP funded dozens of civil rights cases in the Southwest during the early 1950's and repre- sented the first large-scale effort by Mexican Americans to establish a national civil rights organization. As such, ACSSP was a precursor of the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund (MALDEF) and other organizations concerned with protecting the legal rights of Mexican Americans in the Southwest. The period covered here extends from 1940 to 1960, two crucial decades when Mexican Ameri- cans made a concerted effort to challenge segregation in public schools, discrimination in housing and employment, and the denial of equal ac- cess to public places such as theaters, restaurants, and barber shops. Although Mexican Americans are still confronted today by de facto seg- regation and job discrimination, it is of historical and legal interest that Mexican American legal victories, in areas such as school desegregation, predated by many years the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education and the civil rights movement of the 1960's. Sanchez' pioneering leadership and the activities of ACSSP merit exami- nation if we are to fully comprehend the historical struggle of the Mexi- can American civil rights movement. In a recent article, Karen O'Conner and Lee Epstein traced the ori- gins of MALDEF to the 1960's civil rights era.' The authors argued that "Chicanos early on recongized their inability to seek rights through traditional political avenues and thus sporadically resorted to litigation .. -

Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. ____~____ ~:-:'----;-- - ~-- ----;--;:-'l~. - Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress ,. In 1967, the Department published a report, Texas Department of Corrections: 20 Years of Progress. That report was largely the work of Mr. Richard C. Jones, former Assistant Director for Treatment. The report that follows borrowed hea-vily and in many cases directly from Mr. Jones' efforts. This is but another example of how we continue to profit from, and, hopefully, build upon the excellent wC';-h of those preceding us. Texas Department of Corrections: 30 Years of Progress NCJRS dAN 061978 ACQUISIT10i~:.j OFFICE OF THE GOVERNOR DOLPH BRISCOE STATE CAPITOL GOVERNOR AUSTIN, TEXAS 78711 My Fellow Texans: All Texans owe a debt of gratitude to the Honorable H. H. Coffield. former Chairman of the Texas Board of Corrections, who recently retired after many years of dedicated service on the Board; to the present members of the Board; to Mr. W. J. Estelle, Jr., Director of the Texas Department of Corrections; and to the many people who work with him in the management of the Department. Continuing progress has been the benchmark of the Texas Department of Corrections over the past thirty years. Proposed reforms have come to fruition through the careful and diligent management p~ovided by successive administ~ations. The indust~ial and educational p~ograms that have been initiated have resulted in a substantial tax savings for the citizens of this state and one of the lowest recidivism rates in the nation. -

Fortress of Liberty: the Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law

Fortress of Liberty: The Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law Jeremy K. Kessler∗ Introduction: Civil Liberty in a Conscripted Age Between 1917 and 1973, the United States fought its wars with drafted soldiers. These conscript wars were also, however, civil libertarian wars. Waged against the “militaristic” or “totalitarian” enemies of civil liberty, each war embodied expanding notions of individual freedom in its execution. At the moment of their country’s rise to global dominance, American citizens accepted conscription as a fact of life. But they also embraced civil liberties law – the protections of freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly, and procedural due process – as the distinguishing feature of American society, and the ultimate justification for American military power. Fortress of Liberty tries to make sense of this puzzling synthesis of mass coercion and individual freedom that once defined American law and politics. It also argues that the collapse of that synthesis during the Cold War continues to haunt our contemporary legal order. Chapter 1: The World War I Draft Chapter One identifies the WWI draft as a civil libertarian institution – a legal and political apparatus that not only constrained but created new forms of expressive freedom. Several progressive War Department officials were also early civil libertarian innovators, and they built a system of conscientious objection that allowed for the expression of individual difference and dissent within the draft. These officials, including future Supreme Court Justices Felix Frankfurter and Harlan Fiske Stone, believed that a powerful, centralized government was essential to the creation of a civil libertarian nation – a nation shaped and strengthened by its diverse, engaged citizenry. -

The Department of Justice and the Limits of the New Deal State, 1933-1945

THE DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE AND THE LIMITS OF THE NEW DEAL STATE, 1933-1945 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY AND THE COMMITTEE ON GRADUATE STUDIES OF STANFORD UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Maria Ponomarenko December 2010 © 2011 by Maria Ponomarenko. All Rights Reserved. Re-distributed by Stanford University under license with the author. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 United States License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/us/ This dissertation is online at: http://purl.stanford.edu/ms252by4094 ii I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. David Kennedy, Primary Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Richard White, Co-Adviser I certify that I have read this dissertation and that, in my opinion, it is fully adequate in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mariano-Florentino Cuellar Approved for the Stanford University Committee on Graduate Studies. Patricia J. Gumport, Vice Provost Graduate Education This signature page was generated electronically upon submission of this dissertation in electronic format. An original signed hard copy of the signature page is on file in University Archives. iii Acknowledgements My principal thanks go to my adviser, David M. -

June 1-15, 1972

RICHARD NIXON PRESIDENTIAL LIBRARY DOCUMENT WITHDRAWAL RECORD DOCUMENT DOCUMENT SUBJECT/TITLE OR CORRESPONDENTS DATE RESTRICTION NUMBER TYPE 1 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/2/1972 A Appendix “B” 2 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/5/1972 A Appendix “A” 3 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/6/1972 A Appendix “A” 4 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/9/1972 A Appendix “A” 5 Manifest Helicopter Passenger Manifest – 6/12/1972 A Appendix “B” COLLECTION TITLE BOX NUMBER WHCF: SMOF: Office of Presidential Papers and Archives RC-10 FOLDER TITLE President Richard Nixon’s Daily Diary June 1, 1972 – June 15, 1972 PRMPA RESTRICTION CODES: A. Release would violate a Federal statute or Agency Policy. E. Release would disclose trade secrets or confidential commercial or B. National security classified information. financial information. C. Pending or approved claim that release would violate an individual’s F. Release would disclose investigatory information compiled for law rights. enforcement purposes. D. Release would constitute a clearly unwarranted invasion of privacy G. Withdrawn and return private and personal material. or a libel of a living person. H. Withdrawn and returned non-historical material. DEED OF GIFT RESTRICTION CODES: D-DOG Personal privacy under deed of gift -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATION *U.S. GPO; 1989-235-084/00024 NA 14021 (4-85) THF WHITE ,'OUSE PRESIDENT RICHARD NIXON'S DAILY DIARY (Sec Travel Record for Travel AnivilY) f PLACE DAY BEGAN DATE (Mo., Day. Yr.) _u.p.-1:N_E I, 1972 WILANOW PALACE TIME DAY WARSAW, POLi\ND 7;28 a.m. THURSDAY PHONE TIME P=Pl.ccd R=Received ACTIVITY 1----.,------ ----,----j In Out 1.0 to 7:28 P The President requested that his Personal Physician, Dr. -

A Counterintelligence Reader, Volume 2 Chapter 1, CI in World

CI in World War II 113 CHAPTER 1 Counterintelligence In World War II Introduction President Franklin Roosevelts confidential directive, issued on 26 June 1939, established lines of responsibility for domestic counterintelligence, but failed to clearly define areas of accountability for overseas counterintelligence operations" The pressing need for a decision in this field grew more evident in the early months of 1940" This resulted in consultations between the President, FBI Director J" Edgar Hoover, Director of Army Intelligence Sherman Miles, Director of Naval Intelligence Rear Admiral W"S" Anderson, and Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A" Berle" Following these discussions, Berle issued a report, which expressed the Presidents wish that the FBI assume the responsibility for foreign intelligence matters in the Western Hemisphere, with the existing military and naval intelligence branches covering the rest of the world as the necessity arose" With this decision of authority, the three agencies worked out the details of an agreement, which, roughly, charged the Navy with the responsibility for intelligence coverage in the Pacific" The Army was entrusted with the coverage in Europe, Africa, and the Canal Zone" The FBI was given the responsibility for the Western Hemisphere, including Canada and Central and South America, except Panama" The meetings in this formative period led to a proposal for the organization within the FBI of a Special Intelligence Service (SIS) for overseas operations" Agreement was reached that the SIS would act -

Guide to Material at the LBJ Library Pertaining to Political Affairs

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON L I B R A R Y & M U S E U M www.lbjlibrary.org Rev. 11/2002, 6/2010, 7/2011 PL MATERIAL AT THE LBJ LIBRARY PERTAINING TO POLITICAL AFFAIRS INTRODUCTION This list includes the principal files in the Johnson Library that contain material relating to political affairs. It is not definitive, however, and researchers should consult with the Library's archivists about other potentially useful files. The guide includes those collections that have been opened for research in part or in whole, and those collections that are currently unprocessed or unavailable. See also the guides: Congress; Public Opinion Polls and Mail; Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP); New Hampshire Politics; The President’s Club; Public Opinion Polls and Mail; 1968-69 Presidential Transition; Whistle Stop; plus those for individuals such as Barry Goldwater, Robert F. Kennedy, etc. WHITE HOUSE CENTRAL FILES (WHCF), SUBJECT FILE This permanent white House office was the main filing unit during the Johnson presidency, though not the primary file for foreign policy documents. Material was filed under 60 major subject headings, as described in the WHCF finding aid. Box # FG, Federal Government Organizations FG 1, The President of the United States 9-35 FG 400, The Legislative Branch 321-330 FG 410, House of Representatives 332-333 FG 411, House Committees 333-337 FG 412, Speaker of the House 337-338 FG 415, Joint Committees of Congress 338-339 FG 430, Senate 339-340 FG 431, Senate Committees 341-346 FG 440, Vice President of the United States 346-351 -

Principal State and Territorial Officers

/ 2 PRINCIPAL STATE AND TERRITORIAL OFFICERS EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Atlorneys .... State Governors Lieulenanl Governors General . Secretaries of State. Alabama. James E. Foisoin J.C.Inzer .A. .A.. Carniichael Sibyl Pool Arizona Dan E. Garvey None Fred O. Wilson Wesley Boiin . Arkansas. Sid McMath Nathan Gordon Ike Marry . C. G. Hall California...... Earl Warren Goodwin J. Knight • Fred N. Howser Frank M. Jordan Colorado........ Lee Knous Walter W. Jolinson John W. Metzger George J. Baker Connecticut... Chester Bowles Wm. T. Carroll William L. Hadden Mrs. Winifred McDonald Delaware...:.. Elbert N. Carvel A. duPont Bayard .Mbert W. James Harris B. McDowell, Jr. Florida.. Fuller Warren None Richard W. Ervin R.A.Gray Georgia Herman Talmadge Marvin Griffin Eugene Cook Ben W. Fortson, Jr. * Idaho ;C. A. Robins D. S. Whitehead Robert E. Sniylie J.D.Price IlUnola. .-\dlai E. Stevenson Sher^vood Dixon Ivan.A. Elliott Edward J. Barrett Indiana Henry F. Schricker John A. Walkins J. Etnmett McManamon Charles F. Fleiiiing Iowa Wm. S.'Beardsley K.A.Evans Robert L. Larson Melvin D. Synhorst Kansas Frank Carlson Frank L. Hagainan Harold R. Fatzer (a) Larry Ryan Kentucky Earle C. Clements Lawrence Wetherby A. E. Funk • George Glenn Hatcher Louisiana Earl K. Long William J. Dodd Bolivar E. Kemp Wade O. Martin. Jr. Maine.. Frederick G. Pgynp None Ralph W. Farris Harold I. Goss Maryland...... Wm. Preston Lane, Jr. None Hall Hammond Vivian V. Simpson Massachusetts. Paul A. Dever C. F. Jeff Sullivan Francis E. Kelly Edward J. Croiiin Michigan G. Mennen Williams John W. Connolly Stephen J. Roth F. M. Alger, Jr.- Minnesota.