The Kennedy Administration's Alliance for Progress and the Burdens Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacqueline (Jackie) Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F

JACQUELINE (JACKIE) KENNEDY: HISTORIC CONVERSATIONS ON LIFE WITH JOHN F. KENNEDY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Caroline Kennedy,Michael R. Beschloss | 400 pages | 20 Oct 2011 | Hyperion | 9781401324254 | English | New York, United States Jacqueline (Jackie) Kennedy: Historic Conversations on Life with John F. Kennedy PDF Book Library Locations Map Details. Tone Tone is the feeling that a book evokes in the reader. Working with the staff of the John F. The decision was complicated by my conviction that if my mother had reviewed the transcripts, I have no doubt she would have made revisions. Dec 06, janet Burke rated it it was amazing. So far, reports on the contents of the interview say nothing about her rumored affair with actor William Holden, but they do give us a glimpse of a sassier Jackie. But I never put much thought into the First Lady being an asset to negotiations or that she intimately knew so many statesmen. The sense of time passing was made more acute by the loss of my uncle Teddy and my aunt Eunice in , by Ted Sorensen in , and my uncle Sarge in January I always thought women who were scared of sex loved Adlai. Listening to Jacqueline Kennedy herself, just a few months after her husband's assassination, speak about her husband and some of the impressions he had formed of the various personalities with whom he dealt as President, as well as hearing her own thoughts about the people who served in the Kennedy This illustrated book and CD Set is a priceless gem for anyone with a deep interest in the era when President and Mrs. -

1 March 1961 Special Distribution

GENERAL AGREEMENT ON RESTRICTEDC/W/16 TARIFFS AND TRADE 1 March 1961 Special Distribution COUNCIL 22 February - 3 March 1961 CONCLUSIONS REACHED BY COUNCIL Drafts The following drafts of conclusions reached by the Council on certain items of its agenda are submitted for approval, (It should be understood that in the minutes of the Council's meeting these conclusions will in each case be preceded by a short statement of the question under discussion and by a note on the trend of the discussion.) Item 2: Provisional accession of Switzerland It was agreed that the consultations with Switzerland in accordance with the terms of the Declaration on the Provisional Accession of Switzerland should be continued. For this purpose, a small group of contracting parties, drawn mainly from important agricultural exporters to the Swiss market was appointed, with the following membership: Australia Netherlands Canada New ZealAnd Denmark United States France Uruguay Other contracting parties which considered that they had an important interest in the products covered by Switzerlands reservation in the Declaration would be free to participate in the work of the group. The group would meet on 6 and 7 April. It was felt that it should be possible for the group, at that meeting, to suggest a time-table for the completion of the discussions with Switzerland, after which it would submit a report either to a meeting of the Council or to a session of the CONTRACTING PARTIES, whichever was the earlier. Item5: Uruguayan import surcharges It was noted that the delegation of Uruguay had transmitted to the secretariat a list of the bound items affected by the surcharges, as well as the text of the Decree of 29 September 1960 :imposing the surcharges, end that these would be circulated to contracting parties as soon as possible, It was agreed that, in view of the limited time available, it would not be possible to deal with this item at the present meeting of the Council and that it should be discussed at the next meeting of the Council. -

United States Cold War Policy, the Peace Corps and Its Volunteers in Colombia in the 1960S

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s. John James University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation James, John, "United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3630. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3630 UNITED STATES COLD WAR POLICY, THE PEACE CORPS AND ITS VOLUNTEERS IN COLOMBIA IN THE 1960s by J. BRYAN JAMES B.A. Florida State University, 1994 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2008 ABSTRACT John F. Kennedy initiated the Peace Corps in 1961 at the height of the Cold War to provide needed manpower and promote understanding with the underdeveloped world. This study examines Peace Corps work in Colombia during the 1960s within the framework of U.S. Cold War policy. It explores the experiences of volunteers in Colombia and contrasts their accounts with Peace Corps reports and presentations to Congress. -

Director of Dounreay: Mr. RR Matthews

NO.4871 March 9, 1963 NATURE 953 was educated at the Imperial College of Science and decide before the end of the year whether a prototype Technology, where he obtained the degree of B.Sc.(Eng.) nuclear ship would be built. In these circumstances, the in 1953 and five years later was awarded the degree of Government had decided that the time had come to have Ph.D. Following graduation, Dr. Clarricoats was em discussions with the shipping and shipbuilding industries ployed by the General Electric Company at Stanmore about the arrangements for such a ship. It was expected until 1958, when he was appointed lecturer in the Depart that it would be possible to decide before the end of the ment of Light Electrical Engineering in the Queen's year which reactor system should be installed in a proto University of Belfast. There he created a microwave type nuclear ship, if one is built. The Civil Lord of the research group and arranged contracts with the Depart Admiralty, Mr. C. Ian Orr-Ewing, added that the nent of Scientific and Industrial Research and the Admiralty had no present plans for building a nuclear Ministry of Aviation, which provided apparatus and powered surface vessel, but was keeping in close touch grants. In 1962, he was appointed lecturer in the with the latest developments and applying the knowle?-ge Department of Electrical Engineering at the University gained from them to studies of possible future warshIps, of Sheffield. He was awarded two premiums by the Institution of Electrical Engineers for his work on Teaching Machines and Programme Learning microwave ferrites. -

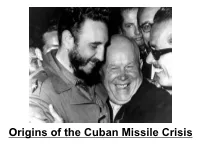

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’S Thesis “It Is Not Enough for the State That Wishes to Maintain Peace and the Status Quo to Have Superior Power

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’s Thesis “It is not enough for the state that wishes to maintain peace and the status quo to have superior power. The [Cuban Missile] Crisis came because the more powerful state also had a leader who failed to convince his opponent of his will to use its power for that purpose” (548). Background • 1/1/1959 – Castro deposes Fulgencio Batista – Still speculation as to whether he was Communist (452) • Feb. 1960 – USSR forges diplomatic ties w/ Castro – July – CUB seizes oil refineries b/c they refused to refine USSR crude • US responds by suspending sugar quota, which was 80% of Cuban exports to USà By October, CUB sells sugar to USSR & confiscates nearly $1B USD invested in CUBà • US implements trade embargo • KAGAN: CUB traded one economic subordination for another (453) Response • Ike invokes Monroe Doctrineà NK says it’s dead – Ike threatens missile strikes if CUB is violated – By Sept. 1960, USSR arms arrive in CUB – KAGAN: NK takes opportunity to reject US hegemony in region; akin to putting nukes in HUN 1956 (454) Nikita, Why Cuba? (455-56) • NK is adventuresome & wanted to see Communism spread around the world • Opportunity prevented itself • US had allies & bases close to USSR. Their turn. • KAGAN: NK was a “true believer” & he was genuinely impressed w/ Castro (456) “What can I say, I’m a pretty impressive guy” – Fidel Bay of Pigs Timeline • March 1960 – Ike begins training exiles on CIA advice to overthrow Castro • 1961 – JFK elected & has to live up to campaign rhetoric against Communism he may not have believed in (Arthur Schlesinger qtd. -

Brazil and the Alliance for Progress

BRAZIL AND THE ALLIANCE FOR PROGRESS: US-BRAZILIAN FINANCIAL RELATIONS DURING THE FORMULATION OF JOÃO GOULART‟S THREE-YEAR PLAN (1962)* Felipe Pereira Loureiro Assistant Professor at the Institute of International Relations, University of São Paulo (IRI-USP), Brazil [email protected] Presented for the panel “New Perspectives on Latin America‟s Cold War” at the FLACSO-ISA Joint International Conference, Buenos Aires, 23 to 25 July, 2014 ABSTRACT The paper aims to analyze US-Brazilian financial relations during the formulation of President João Goulart‟s Three-Year Plan (September to December 1962). Brazil was facing severe economic disequilibria in the early 1960s, such as a rising inflation and a balance of payments constrain. The Three-Year Plan sought to tackle these problems without compromising growth and through structural reforms. Although these were the guiding principles of the Alliance for Progress, President John F. Kennedy‟s economic aid program for Latin America, Washington did not offer assistance in adequate conditions and in a sufficient amount for Brazil. The paper argues the causes of the US attitude lay in the period of formulation of the Three-Year Plan, when President Goulart threatened to increase economic links with the Soviet bloc if Washington did not provide aid according to the country‟s needs. As a result, the US hardened its financial approach to entice a change in the political orientation of the Brazilian government. The US tough stand fostered the abandonment of the Three-Year Plan, opening the way for the crisis of Brazil‟s postwar democracy, and for a 21-year military regime in the country. -

Fortress of Liberty: the Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law

Fortress of Liberty: The Rise and Fall of the Draft and the Remaking of American Law Jeremy K. Kessler∗ Introduction: Civil Liberty in a Conscripted Age Between 1917 and 1973, the United States fought its wars with drafted soldiers. These conscript wars were also, however, civil libertarian wars. Waged against the “militaristic” or “totalitarian” enemies of civil liberty, each war embodied expanding notions of individual freedom in its execution. At the moment of their country’s rise to global dominance, American citizens accepted conscription as a fact of life. But they also embraced civil liberties law – the protections of freedom of speech, religion, press, assembly, and procedural due process – as the distinguishing feature of American society, and the ultimate justification for American military power. Fortress of Liberty tries to make sense of this puzzling synthesis of mass coercion and individual freedom that once defined American law and politics. It also argues that the collapse of that synthesis during the Cold War continues to haunt our contemporary legal order. Chapter 1: The World War I Draft Chapter One identifies the WWI draft as a civil libertarian institution – a legal and political apparatus that not only constrained but created new forms of expressive freedom. Several progressive War Department officials were also early civil libertarian innovators, and they built a system of conscientious objection that allowed for the expression of individual difference and dissent within the draft. These officials, including future Supreme Court Justices Felix Frankfurter and Harlan Fiske Stone, believed that a powerful, centralized government was essential to the creation of a civil libertarian nation – a nation shaped and strengthened by its diverse, engaged citizenry. -

Organizational Behavior Program March 1962 PUBLICATIONS AND

Organizational Behavior Program March 1962 PUBLICATIONS AND RESEARCH DOCUMENTS - 1960 and 1961 ANDREWS. F. 1904 1630 A Study of Company Sponsored Foundations. New York: Russell Sage Founda• tion, I960, 86 pp. 1844 (See Pelz 1844) Mr. Frank Andrews has contributed substantially to a series of reports con• cerning the performance of scientific and technical personnel. Since these reports constitute an integrated series, they are all listed and described together under the name of the principle author, Dr. Donald C. Pelz, p. 4. B1AKEL0CK, E. 1604 A new look at the new leisure. Administrative Science Quarterly, 1960, 4 (4), 446-467. 1620 (With Platz, A.) Productivity of American psychologists: Quantity versus quality. American Psychologist, 1960, 15 (5), 310-312. 1696 A Durkheimian approach to some temporal problems of leisure. Paper read at the Convention of the Society for the Study of Social Problems, August I960, New York, 16 pp., mimeo. BOWERS. D. 1690R (With Patchen, M.) Factors determining first-line supervision at the Dobeckmun Company, Report II, August 1960, 43 pp., mimeo. 1803R Tabulated agency responses: Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company. September 1961, 242 pp., mimeo. 1872 Some aspects of affiliative behavior in work groups. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The University of Michigan, January 1962. 1847 Some aspects of affiliative behavior in work groups. .Abstract of doctoral dissertation, January 1962, 3 pp., mimeo. Study of life insurance agents and agencies: Methods. Report I, December 1961, 11 pp., mimeo. Insurance agents and agency management: Descriptive summary. Report II, December 1961, 41 pp.., typescript. Plus a few documents from 1962. NOTE: Some items have not been issued ISR publication numbers. -

A Counterintelligence Reader, Volume 2 Chapter 1, CI in World

CI in World War II 113 CHAPTER 1 Counterintelligence In World War II Introduction President Franklin Roosevelts confidential directive, issued on 26 June 1939, established lines of responsibility for domestic counterintelligence, but failed to clearly define areas of accountability for overseas counterintelligence operations" The pressing need for a decision in this field grew more evident in the early months of 1940" This resulted in consultations between the President, FBI Director J" Edgar Hoover, Director of Army Intelligence Sherman Miles, Director of Naval Intelligence Rear Admiral W"S" Anderson, and Assistant Secretary of State Adolf A" Berle" Following these discussions, Berle issued a report, which expressed the Presidents wish that the FBI assume the responsibility for foreign intelligence matters in the Western Hemisphere, with the existing military and naval intelligence branches covering the rest of the world as the necessity arose" With this decision of authority, the three agencies worked out the details of an agreement, which, roughly, charged the Navy with the responsibility for intelligence coverage in the Pacific" The Army was entrusted with the coverage in Europe, Africa, and the Canal Zone" The FBI was given the responsibility for the Western Hemisphere, including Canada and Central and South America, except Panama" The meetings in this formative period led to a proposal for the organization within the FBI of a Special Intelligence Service (SIS) for overseas operations" Agreement was reached that the SIS would act -

Guide to Material at the LBJ Library Pertaining to Foreign Aid and Food

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON L I B R A R Y & M U S E U M www.lbjlibrary.org Revised December 2010 FOREIGN AID, FOOD FOR PEACE, AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN ASIA, AFRICA, AND LATIN AMERICA INTRODUCTION This guide lists the principal files at the Johnson Library that contain material on foreign aid (excluding military assistance programs), food for peace, and economic development in Asia, Africa, and Latin America, but it is not exhaustive. Researchers should also consult the regional guide for additional materials on the geographic areas in which they are interested. While most of the collections listed in the guide have been processed and are available for research, some files may not yet be available. Researchers should consult the Library’s finding aids to locate additional material and to determine whether specific files are available for research. Some of the finding aids are on the Library’s web site, www.lbjlibrary.org, and many others can be sent by mail or electronically. Researchers interested in the topics covered by this guide should also consult the Foreign Relations of the United States. This multi-volume series published by the Office of the Historian of the Department of State presents the official documentary historical record of major foreign policy decisions and diplomatic activity of the United States government. The volumes are available online at the Department of State web site, http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments. NATIONAL SECURITY FILE (NSF) This file was the working file of President Johnson’s special assistants for national security affairs, McGeorge Bundy and Walt W. -

Download Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS AN NUAL RE PORT JULY 1, 2003-JUNE 30, 2004 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, NW 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 434-9800 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www.cfr.org E-mail [email protected] OFFICERS and DIRECTORS 2004-2005 OFFICERS DIRECTORS Term Expiring 2009 Peter G. Peterson* Term Expiring 2005 Madeleine K. Albright Chairman of the Board Jessica P Einhorn Richard N. Fostert Carla A. Hills* Louis V Gerstner Jr. Maurice R. Greenbergt Vice Chairman Carla A. Hills*t Robert E. Rubin George J. Mitchell Vice Chairman Robert E. Rubin Joseph S. Nye Jr. Richard N. Haass Warren B. Rudman Fareed Zakaria President Andrew Young Michael R Peters Richard N. Haass ex officio Executive Vice President Term Expiring 2006 Janice L. Murray Jeffrey L. Bewkes Senior Vice President OFFICERS AND and Treasurer Henry S. Bienen DIRECTORS, EMERITUS David Kellogg Lee Cullum AND HONORARY Senior Vice President, Corporate Richard C. Holbrooke Leslie H. Gelb Affairs, and Publisher Joan E. Spero President Emeritus Irina A. Faskianos Vice President, Vin Weber Maurice R. Greenberg Honorary Vice Chairman National Program and Academic Outreach Term Expiring 2007 Charles McC. Mathias Jr. Elise Carlson Lewis Fouad Ajami Director Emeritus Vice President, Membership David Rockefeller Kenneth M. Duberstein and Fellowship Affairs Honorary Chairman Ronald L. Olson James M. Lindsay Robert A. Scalapino Vice President, Director of Peter G. Peterson* t Director Emeritus Studies, Maurice R. Creenberg Chair Lhomas R. -

Killing Hope U.S

Killing Hope U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II – Part I William Blum Zed Books London Killing Hope was first published outside of North America by Zed Books Ltd, 7 Cynthia Street, London NI 9JF, UK in 2003. Second impression, 2004 Printed by Gopsons Papers Limited, Noida, India w w w.zedbooks .demon .co .uk Published in South Africa by Spearhead, a division of New Africa Books, PO Box 23408, Claremont 7735 This is a wholly revised, extended and updated edition of a book originally published under the title The CIA: A Forgotten History (Zed Books, 1986) Copyright © William Blum 2003 The right of William Blum to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Cover design by Andrew Corbett ISBN 1 84277 368 2 hb ISBN 1 84277 369 0 pb Spearhead ISBN 0 86486 560 0 pb 2 Contents PART I Introduction 6 1. China 1945 to 1960s: Was Mao Tse-tung just paranoid? 20 2. Italy 1947-1948: Free elections, Hollywood style 27 3. Greece 1947 to early 1950s: From cradle of democracy to client state 33 4. The Philippines 1940s and 1950s: America's oldest colony 38 5. Korea 1945-1953: Was it all that it appeared to be? 44 6. Albania 1949-1953: The proper English spy 54 7. Eastern Europe 1948-1956: Operation Splinter Factor 56 8. Germany 1950s: Everything from juvenile delinquency to terrorism 60 9. Iran 1953: Making it safe for the King of Kings 63 10.