Brazil and the Alliance for Progress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems , Vol

ISSN 1848 -9257 Journal of Sustainable Development Journal of Sustainable Development of Energy, Water of Energy, Water and Environment Systems and Environment Systems http://www.sdewes.org/jsdewes http://www.sdewes.org/jsdewes Year 2018, Volume 6, Issue 3, pp 559-608 Application of the Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems Index to World Cities with a Normative Scenario for Rio de Janeiro Şiir Kılkış The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (TÜB İTAK), Atatürk Bulvarı No: 221, Kavaklıdere 06100, Ankara, Turkey e-mail: siir.kilkis @tubitak.gov.tr Cite as: Kilki ş, Ş., Application of the Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems Index to World Cities with a Normative Scenario for Rio de Janeiro, J. sustain. dev. energy water environ. syst., 6(3), pp 559-608, 2018, DOI: https://doi.org/10.13044/j.sdewes.d6.0213 ABSTRACT Urban sustainability is one of the most prominent challenges in the global agenda waiting to be addressed since the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. This research work applies a composite indicator that has been developed as the Sustainable Development of Energy, Water and Environment Systems Index to benchmark the performance of a new sample of 26 world cities. The sample advances the geographical diversity of previous samples and represents cities in the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate and Energy as well as the C40 initiative. The benchmarking results are analysed based on quartiles of city performance and Monte Carlo simulations. The results indicate the top three cities in the sample to be Copenhagen, which obtains a score of 36.038, followed by Helsinki and Gothenburg. -

NATO Expansion: Benefits and Consequences

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2001 NATO expansion: Benefits and consequences Jeffrey William Christiansen The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Christiansen, Jeffrey William, "NATO expansion: Benefits and consequences" (2001). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8802. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8802 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ■rr - Maween and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of M ontana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission X No, I do not grant permission ________ Author's Signature; Date:__ ^ ^ 0 / Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. MSThe»i9\M«r«f»eld Library Permission Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NATO EXPANSION: BENEFITS AND CONSEQUENCES by Jeffrey William Christiansen B.A. University of Montana, 2000 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The University of Montana 2001 Approved by: hairpers Dean, Graduate School 7 - 24- 0 ^ Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Regulatory Shortcomings of Brazilian Social Security

ISSN 1022-4057 Português English Español E CONOMIC A NALYSIS OF L AW R EVIEW www.ealr.com.br EALR, V. 1, nº 1, p. 145-164, Jan-Jun, 2010 EEconomic AAnalysis of LLaw RReview Regulatory Shortcomings of Brazilian Social Security Riovaldo Alves de Mesquita 1 Giácomo Balbinotto Neto 2 Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Programa de Pós-Graduação em Economia Programa de Pós-Graduação em Economia RESUMO ABSTRACT A assistência e previdência social brasileira são Brazil’s social security and social assistance muito caras em relação ao perfil etário e de provisions are too expensive and becoming more renda do país. Uma causa disso é a indexação so relative to the country’s age profile and per dos pisos de benefícios ao salário mínimo, feita capita GDP. One reason for this is the fact that na Constituição de 1988. Outras causas são: a in the1988 Constitution social security pensions baixa idade de elegibilidade aos benefícios, os were indexed to the minimum wage. Other valores relativamente altos de benefícios, um reasons are low eligibility age, high pensions período mínimo de contribuição relativamente relative to past contributions, a short minimum curto, a possibilidade de os beneficiários contribution period, the possibility of acumularem mais de um tipo de benefício e o accumulating different benefits and the fact that caráter assistencialista de alguns benefícios. As some social security benefits are dispensed as projeções populacionais indicam que, em 2050, social assistance benefits. In 2050 Brazilians 65 os brasileiros com 65 anos ou mais or older will represent 23% of total population, representarão cerca de 23% da população total e while the workforce will be shrinking. -

The Role of Mncs in China and Brazil's Foreign Policy Towards Developing States in Africa

The role of MNCs in China and Brazil’s foreign policy towards developing states in Africa NUšA TUKIć DISSERTATION PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES AT STELLENBOSCH UNIVERSITY SUPERVISOR: DR SVEN GRIMM CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF JANIS VAN DER WESTHUIZEN MARCH 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT While most international political economy (IPE) literature has been concerned with the relations between multinational corporations (MNCs) and the host states in which they operate, this study sought to contribute to general state-MNC relations by looking at the other dimension, namely home state-MNC relations. In addition, while home state-MNC literature mostly focuses on how this relationship plays out in the domestic realm; this study focused on home state-MNC relations in foreign policy. A further limitation was to only look at home state-MNC relations in the developing world by using China and Brazil as the main case studies, and their interaction with MNCs in foreign policy towards developing states from Africa. The research design was comparative, using the most similar system case selections. -

United States Cold War Policy, the Peace Corps and Its Volunteers in Colombia in the 1960S

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2008 United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s. John James University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation James, John, "United States Cold War Policy, The Peace Corps And Its Volunteers In Colombia In The 1960s." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 3630. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/3630 UNITED STATES COLD WAR POLICY, THE PEACE CORPS AND ITS VOLUNTEERS IN COLOMBIA IN THE 1960s by J. BRYAN JAMES B.A. Florida State University, 1994 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2008 ABSTRACT John F. Kennedy initiated the Peace Corps in 1961 at the height of the Cold War to provide needed manpower and promote understanding with the underdeveloped world. This study examines Peace Corps work in Colombia during the 1960s within the framework of U.S. Cold War policy. It explores the experiences of volunteers in Colombia and contrasts their accounts with Peace Corps reports and presentations to Congress. -

Brexit and the Future of the US–EU and US–UK Relationships

Special relationships in flux: Brexit and the future of the US–EU and US–UK relationships TIM OLIVER AND MICHAEL JOHN WILLIAMS If the United Kingdom votes to leave the European Union in the referendum of June 2016 then one of the United States’ closest allies, one of the EU’s largest member states and a leading member of NATO will negotiate a withdrawal from the EU, popularly known as ‘Brexit’. While talk of a UK–US ‘special relation- ship’ or of Britain as a ‘transatlantic bridge’ can be overplayed, not least by British prime ministers, the UK is a central player in US–European relations.1 This reflects not only Britain’s close relations with Washington, its role in European security and its membership of the EU; it also reflects America’s role as a European power and Europe’s interests in the United States. A Brexit has the potential to make a significant impact on transatlantic relations. It will change both the UK as a country and Britain’s place in the world.2 It will also change the EU, reshape European geopolitics, affect NATO and change the US–UK and US–EU relationships, both internally and in respect of their place in the world. Such is the potential impact of Brexit on the United States that, in an interview with the BBC’s Jon Sopel in summer 2015, President Obama stated: I will say this, that having the United Kingdom in the European Union gives us much greater confidence about the strength of the transatlantic union and is part of the corner- stone of institutions built after World War II that has made the world safer and more prosperous. -

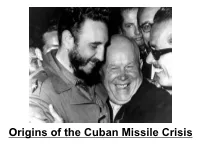

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’S Thesis “It Is Not Enough for the State That Wishes to Maintain Peace and the Status Quo to Have Superior Power

Origins of the Cuban Missile Crisis Kagan’s Thesis “It is not enough for the state that wishes to maintain peace and the status quo to have superior power. The [Cuban Missile] Crisis came because the more powerful state also had a leader who failed to convince his opponent of his will to use its power for that purpose” (548). Background • 1/1/1959 – Castro deposes Fulgencio Batista – Still speculation as to whether he was Communist (452) • Feb. 1960 – USSR forges diplomatic ties w/ Castro – July – CUB seizes oil refineries b/c they refused to refine USSR crude • US responds by suspending sugar quota, which was 80% of Cuban exports to USà By October, CUB sells sugar to USSR & confiscates nearly $1B USD invested in CUBà • US implements trade embargo • KAGAN: CUB traded one economic subordination for another (453) Response • Ike invokes Monroe Doctrineà NK says it’s dead – Ike threatens missile strikes if CUB is violated – By Sept. 1960, USSR arms arrive in CUB – KAGAN: NK takes opportunity to reject US hegemony in region; akin to putting nukes in HUN 1956 (454) Nikita, Why Cuba? (455-56) • NK is adventuresome & wanted to see Communism spread around the world • Opportunity prevented itself • US had allies & bases close to USSR. Their turn. • KAGAN: NK was a “true believer” & he was genuinely impressed w/ Castro (456) “What can I say, I’m a pretty impressive guy” – Fidel Bay of Pigs Timeline • March 1960 – Ike begins training exiles on CIA advice to overthrow Castro • 1961 – JFK elected & has to live up to campaign rhetoric against Communism he may not have believed in (Arthur Schlesinger qtd. -

The Conflict Over Veracel Pulpwood Plantations in Brazil — Application of Ethical Analysis

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto The conflict over Veracel pulpwood plantations in Brazil — Application of Ethical Analysis · Markus Krögera, b, , , · Jan-Erik Nylunda, · a Dept. of Forest Products, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, PO Box 7008, SE-750 07, Uppsala, Sweden · b Department of Political and Economic Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Helsinki, P.O., Box 54, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland Forest Policy and Economics 14 (2012) 74–82 Post-print version. For original, and page numbers, please see: doi:10.1016/j.forpol.2011.07.018 Corresponding author at: Department of Political and Economic Studies, P.O. Box 54, 00014 University of Helsinki, Finland. Fax: + 358 919124835. E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract The large-scale pulp investment model, with its pressure on land, has created conflict and caused major disagreements and open hostility amongst the social movement and NGO networks, state actors, and the pulp and paper companies in Brazil. In this article, Ethical Analysis was applied in the assessment of the dynamics and possibilities of conflict resolution related to the expansion of pulpwood plantations in Brazil's Bahia State, particularly near Veracel Celulose. Ethical Analysis as a tool identifies the complex dynamics of contention through identifying bridges and rifts in the social, ecological and economic viewpoints of the main actors. The analysis was based on field research, interviews, and a review of existing literature. The results indicated that the conflict is marked by politics of power, and as long as this stage continues, the politics of cooperation and conflict resolution would be hard to achieve. -

The Thickness of Time: the Writing of History and Appropriation of the Past in Brazil, 1830–1930

Volumes Abstract Sections Formats Info EKT top CONTENTS Vol 17.1 (2018): Brazilian Historiography: memory, time and Helena Miranda Mollo, Rodrigo Turin, Fernando Nicolazzi The thickness of time: knowledge in the writing of history the writing of history and appropriation of the past in Brazil, 1830–1930 INTRODUCTION Introduction ARTICLES The thickness of time: the writing of history and appropriation of the past in Ordering time, nationalising the past: temporality, Brazil, 1830–1930 historiography and Brazil’s “formation” Helena Miranda Mollo The forms of history in the nineteenth century: the regimes of autonomy in Brazilian historiography Federal University of Ouro Preto The thickness of time: the writing of history and Rodrigo Turin appropriation of the past in Brazil, 1830–1930 Federal University of the State of Rio de Janeiro Ethics, present time and memory in Brazilian journals of history, 1981–2014 Fernando Nicolazzi Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul BOOK REVIEWS Review of Erol, Greek Orthodox Music in Ottoman Istanbul: Nation and Community in the Era of Reform Since the late 1980s, the recent1 Brazilian history of historiography has perceived the nineteenth century as a period Review of Gallant, Modern Greece: from the War of 1 crammed with several peculiarities. By beginning with a brief presentation on the Brazilian history of historiography, it is Independence to the Present, 2nd ed. possible to affirm that the construction of the nation was one of its main lines of investigation.2 Review of Karakatsouli, «Μαχητές της ελευθερίας» The origin of Brazil was inevitably connected to the Portuguese expansion; however, its genealogy, strictly linked to και 1821: Η ελληνική επανάσταση στη διεθνική της 2 διάσταση [“Freedom fighters” and 1821: the Greek Portugal, was an issue for the literates writing the country’s history after liberation from Portugal, in 1822. -

SPECIAL RELATIONSHIPS Australia and New Zealand in the Anglo-American World1

8 SPECIAL RELATIONSHIPS Australia and New Zealand in the Anglo-American World1 David MacDonald and Brendon O’Connor In this chapter, we argue that the extensive range of Australia’s and New Zealand’s (NZ) foreign policy activities – including their involvement in numerous foreign wars since the Boer War – can be best explained by the special relations both nations have maintained with the broader Anglo-American world. Strong bonds of shared interests, history, culture, and other commonalities have proven durable and demonstrably influential in determining the priorities and actions of both Antipodean countries. The “imagined community” of the Anglo-American world, strengthened by regular economic, military, and diplomatic interactions, possesses significant ideational power. Such bonds have also been affected by emotional beliefs, as Mercer puts it, “a generalization about an actor that involves certainty beyond evidence.” 2 These beliefs are expressed either as positive sentiments towards fellow members of the Anglo-American world, or as distrust of “others” like Japan, Indonesia, or China. The origin and nature of these emotional and ideational ties are key foci of our chapter. Arguably, European settlement of both countries has had a long-term impact, orienting both nations towards Britain, the USA, and other white settler societies (and to a lesser extent non-white British colonies and ex-British colonies) for most of their histories. The resulting strategic culture helps to explain the extremely close security and cultural alliances with the USA and Britain, which we will dissect in detail. Both of our case studies are clearly part of the “West,” even if that West, to echo Peter Katzenstein, is a plural and pluralist entity, often difficult to define as it is evolving and changing. -

Contemporary Civil-Military Relations in Brazil and Argentina : Bargaining for Political Reality

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1996 Contemporary civil-military relations in Brazil and Argentina : bargaining for political reality. Carlos P. Baía University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Baía, Carlos P., "Contemporary civil-military relations in Brazil and Argentina : bargaining for political reality." (1996). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2541. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2541 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. c CONTEMPORARY CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA BARGAINING FOR POLITICAL REALITY A Thesis Presented by CARLOS P. BAIA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 1996 Political Science © Copyright by Carlos Pereira Bafa 1996 All Rights Reserved CONTEMPORARY CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS IN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA BARGAINING FOR POLITICAL REALITY A Thesis Presented by CARLOS P. BAIA Approved as to style and content by: Howard Wiarda, Chair Eric Einhorn, Member Eric Einhom, Department Head Political Science ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would not have been possible without the invaluable contributions of Howard Wiarda, Eric Einhorn, Timothy Steingega, Anthony Spanakos, Moise Tirado, Tilo Stolz, Edgar Brignoni, Susan Iwanicki, and Larissa Ruiz. To them I express my sincere gratitude. I also owe special thanks to the United States Department of Education for granting me a Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship to complete this research. -

SLAR Mosaics for Project RADAM

FRONTISPIECEReproduction of a portion of a semi-eontrolled SLAR mosaic. JANW. VAN ROESSEL Earth Satellite Corp. Berkeley, Cali$ 94704 ROGERIOC. DE GODOY Ministerio das Minus e Energia Rio AJaneiro GB, Brazil SLAR Mosaics for Project RADAM Semi-controlled mosaics made with side-looking radar imagery comprise one of the mapping products of the Amazon and the Brazilian Northeast. (Abstract on next page) INTRODUCTION a standard map product with a certain NTIL THE organization of Project ADA AM (for geometric accuracy. U~adar~mazon) in October 1970, the To date, the minor o1,jective has almost Brazilian Amazoil Basin was one of the been acco~nplished:160 semi-controlled SLAR largest poorly mapped areas in the world. At mosaic sheets have been released for pul~lic that time, however, the Brazilian government use. Each inosaic sheet covers a rectangular decided to undertake a reconnaissance sur- area of 1 degree latitudinally by 1.5 degrees vey of the Amazon and the adjacent Brazilian longitudinally. Preliminary checks have in- Northeast in a most unconventional manner, dicated that the geometric accuracy of each namely, by executing the largest commercial sheet and of the overall nlosaic can be ex- side-looking radar (SLAR)remote-sensing proj- pected to be well within the contractual re- ect ever undertaken. quiren~ents,which will be described pres- The major objective was to collect informa- ently. tion on mineral resources, soils, vegetation, Mapping such an extensive area in such a and land use; a minor objective was to obtain short period required an uncoilventional PHOTOGRAMMETRIC ENGINEERING, 1974 mapping tool, for which only SLAR qualified reliable cartographic delineations, a certain because of its capability to penetrate clouds.