ISO 639-3 Code Split Request Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Computational Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Pama-Nyungan Verb Conjugation Classes

Abstract Computational Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Pama-Nyungan Verb Conjugation Classes Parker Lorber Brody 2020 The Pama-Nyungan language family comprises some 300 Indigenous languages, span- ning the majority of the Australian continent. The varied verb conjugation class systems of the modern Pama-Nyungan languages have been the object of contin- ued interest among researchers seeking to understand how these systems may have changed over time and to reconstruct the verb conjugation class system of the com- mon ancestor of Pama-Nyungan. This dissertation offers a new approach to this task, namely the application of Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction models, which are employed in both testing existing hypotheses and proposing new trajectories for the change over time of the organization of the verbal lexicon into inflection classes. Data from 111 Pama-Nyungan languages was collected based on features of the verb conjugation class systems, including the number of distinct inflectional patterns and how conjugation class membership is determined. Results favor reconstructing a re- stricted set of conjugation classes in the prehistory of Pama-Nyungan. Moreover, I show evidence that the evolution of different parts of the conjugation class sytem are highly correlated. The dissertation concludes with an excursus into the utility of closed-class morphological data in resolving areas of uncertainty in the continuing stochastic reconstruction of the internal structure of Pama-Nyungan. Computational Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Pama-Nyungan Verb Conjugation Classes A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Yale University in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Parker Lorber Brody Dissertation Director: Dr. Claire Bowern December 2020 Copyright c 2020 by Parker Lorber Brody All rights reserved. -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

Annual Report 2016 - 2017 Letter of Transmittal

Queensland South Native Title Services ANNUAL REPORT 2016 - 2017 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Senator the Hon Nigel Scullion Minister for Indigenous Affairs Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 26 October 2017 Dear Minister We are pleased to present the 2016-17 Annual Report for Queensland South Native Title Services Limited (QSNTS). This report is provided in accordance with the Australian Government’s Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC) terms and conditions relating to the native title funding agreement under s 203FE(1) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA). The report includes independently audited financial statements for the financial year ending 30 June 2017. Thank you for your ongoing support of the work QSNTS is undertaking. Yours sincerely Chair, Board of Directors Queensland South Native Title Services Annual Report 2016 – 2017 | i TABLE OF CONTENTS Letter of Transmittal ...................................................................................................................................................i Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................................01 Glossary ...................................................................................................................................................................03 Contact Details.......................................................................................................................................................04 -

Salvage Studies of Western Queensland Aboriginallanguages

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series B-1 05 SALVAGE STUDIES OF WESTERN QUEENSLAND ABORIGINALLANGUAGES Gavan Breen Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Breen, G. Salvage studies of a number of extinct Aboriginal languages of Western Queensland. B-105, xii + 177 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1990. DOI:10.15144/PL-B105.cover ©1990 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES C: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurrn EDITORIAL BOARD: K.A. Adelaar, T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: BW. Be nder K.A. McElha no n Univers ity ofHa waii Summer Institute of Linguis tics David Bra dle y H. P. McKaughan La Trobe Univers ity Unive rsityof Hawaii Mi chael G.Cl yne P. Miihlhll usler Mo nash Univers ity Bond Univers ity S.H. Elbert G.N. O' Grady Uni ve rs ity ofHa waii Univers ity of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Frank li n K. L. Pike SummerIn stitute ofLingui s tics SummerIn s titute of Linguis tics W.W. Glove r E. C. Po lo me SummerIn stit ute of Linguis tics Unive rsity ofTe xas G.W. Grace Gillian Sa nkoff University ofHa wa ii Universityof Pe nns ylvania M.A.K. Halliday W.A. L. -

A Linguistic Bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands

OZBIB: a linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands Dedicated to speakers of the languages of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands and al/ who work to preserve these languages Carrington, L. and Triffitt, G. OZBIB: A linguistic bibliography of Aboriginal Australia and the Torres Strait Islands. D-92, x + 292 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1999. DOI:10.15144/PL-D92.cover ©1999 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: Malcolm D. Ross and Darrell T. Tryon (Managing Editors), John Bowden, Thomas E. Dutton, Andrew K. Pawley Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in linguistic descriptions, dictionaries, atlases and other material on languages of the Pacific, the Philippines, Indonesia and Southeast Asia. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Pacific Linguistics is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian NatIonal University. Pacific Linguistics was established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund. It is a non-profit-making body financed largely from the sales of its books to libraries and individuals throughout the world, with some assistance from the School. The Editorial Board of Pacific Linguistics is made up of the academic staff of the School's Department of Linguistics. The Board also appoints a body of editorial advisors drawn from the international community of linguists. -

J Gavan Breen

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Finding Aid index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library Language collections deposited at AIATSIS by J Gavan Breen 1967-1979 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY 3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT 4 ACCESS TO COLLECTION 4 COLLECTION OVERVIEW 5 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE 8 SERIES DESCRIPTION 9 Series 1 C12 Antekerrepenhe 9 Series 2 G12.1 Bularnu 11 Series 3 N155 Garrwa and G23 Waanyi 12 Series 4 D30 Kullilli 13 Series 5 G8 Yalarnnga 13 Series 6 G13 Kalkatungu and G16 Mayi-Thakurti/Mitakoodi 14 Series 7 G49: Kok Narr 15 Series 8 L38 Kungkari and L36 Pirriya 15 Composite Finding Aid: Language collections; Gavan Breen Series 9 G31 Gkuthaarn and G28 Kukatj 16 Series 10 D42 Margany and D43 Gunya 17 Series 11 D33 Kooma/Gwamu 18 Series 12 E39 Wadjigu 18 Series 13 E32 Gooreng Gooreng 18 Series 14 E60 Gudjal 19 Series 15 E40 Gangulu 19 Series 16 E56 Biri 19 Series 17 D31 Budjari/Badjiri 19 Series 18 D37 Gunggari 20 Series 19 D44 Mandandanji 20 Series 20 G21 Mbara and Y131 Yanga 20 Series 21 L34 Mithaka 21 Series 22 G17 Ngawun 21 Series 23 G6 Pitta Pitta 22 Series 24 C16 Wakaya 23 Series 25 L25 Wangkumara and L26 Punthamara 24 Series 26 G10 Warluwarra 25 Series 27 L18 Yandruwandha 25 Series 28 L23 Yawarrawarrka 26 Series 29 L22 Ngamini 27 Series 30 Reports to AIAS on Field Trips 27 Annex A A "Never say die: Gavan Breen’s life of service to the documentation of Australian Indigenous languages” 29 Annex B Gavan Breen Language Collections Without Finding Aids 50 2 Composite Finding Aid: Language collections; -

Archaeology of Colonisation: a Critical Voyage from the Caribbean to Australia Carlos R

Archaeology of Colonisation: A Critical Voyage from the Caribbean to Australia Carlos R. Rivera Santana B.A., M.A. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 School of Nursing, Midwifery and Social Work Abstract This research is a historical-theoretical examination of how colonisation was operationalised in Queensland, Australia. It argues that colonisation was constituted as a form of government that had two constitutive dimensions: one metaphysical framed by aesthetic judgement and one technico-political framed by administrative functionality. The mapping of both dimensions provides a more accurate description of the operationalisation of colonisation. This research applies a Foucauldian archaeology to the ongoing process of colonisation, and its findings are outlined in two parts. The first part discusses the global origins of how the colonial West first aesthetically conceptualised aboriginality and blackness in the Caribbean, and the second part discusses how this conceptualisation was wielded locally in Queensland through the administrative design of the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act 1897 (1897 Act). Foucauldian archaeology is understood as a historical engagement with the origins of a given notion, concept, or praxis, and with its relationship to forms of governance (Agamben, 2009; Deleuze, 1985; Foucault, 1974). This thesis begins with mapping the global origins of colonisation, which are found in the first European colonial experiences in the Caribbean in the 15th and 16th centuries where the Western conceptualisations of aboriginality and blackness were formed. I argue here that these conceptualisations were aesthetic assemblages that predate the post-Enlightenment discourses of anthropology. -

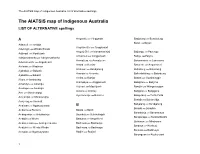

The AIATSIS Map of Indigenous Australia, List of Alternative Spellings

The AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia, list of alternative spellings The AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia LIST OF ALTERNATIVE spellings A Angardie see Yinggarda Badjulung see Bundjalung Baiali see Bayali Adawuli see Iwaidja Angkamuthi see Anggamudi Adetingiti see Winda Winda Angutj Giri see Marramaninjsji Baijungu see Payungu Adjinadi see Mpalitjanh Ankamuti see Anggamudi Bailgu see Palyku Adnjamathanha see Adnyamathanha Anmatjera see Anmatyerre Bakanambia see Lamalama Adumakwithi see Anguthimri Araba see Kurtjar Bakwithi see Anguthimri Airiman see Wagiman Arakwal see Bundjalung Balladong see Balardung Ajabakan see Bakanh Aranda see Arrernte Ballerdokking see Balardung Ajabatha see Bakanh Areba see Kurtjar Banbai see Gumbainggir Alura see Jaminjung Atampaya see Anggamudi Bandjima see Banjima Amandyo see Amangu Atjinuri see Mpalitjanh Bandjin see Wargamaygan Amangoo see Amangu Awara see Warray Bangalla see Banggarla Ami see Maranunggu Ayerrerenge see Bularnu Bangerang see Yorta Yorta Amijangal see Maranunggu Banidja see Bukurnidja Amurrag see Amarak Banjalang see Bundjalung Anaiwan see Nganyaywana B Barada see Baradha Anbarra see Burarra Baada see Bardi Baranbinja see Barranbinya Andagirinja see Antakarinja Baanbay see Gumbainggir Baraparapa see Baraba Baraba Andajin see Worla Baatjana see Anguthimri Barbaram see Mbabaram Andakerebina see Andegerebenha Badimaia see Badimaya Bardaya see Konbudj Andyinit see Winda Winda Badimara see Badimaya Barmaia see Badimaya Anewan see Nganyaywana Badjiri see Budjari Barunguan see Kuuku-yani 1 The -

AIATSIS Lan Ngua Ge T Hesaurus

AIATSIS Language Thesauurus November 2017 About AIATSIS – www.aiatsis.gov.au The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) is the world’s leading research, collecting and publishing organisation in Australian Indigenous studies. We are a network of council and committees, members, staff and other stakeholders working in partnership with Indigenous Australians to carry out activities that acknowledge, affirm and raise awareness of Australian Indigenous cultures and histories, in all their richness and diversity. AIATSIS develops, maintains and preserves well documented archives and collections and by maximising access to these, particularly by Indigenous peoples, in keeping with appropriate cultural and ethical practices. AIATSIS Thesaurus - Copyright Statement "This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use within your organisation. All other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to The Library Director, The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601." AIATSIS Language Thesaurus Introduction The AIATSIS thesauri have been made available to assist libraries, keeping places and Indigenous knowledge centres in indexing / cataloguing their collections using the most appropriate terms. This is also in accord with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Research Network (ATSILIRN) Protocols - http://aiatsis.gov.au/atsilirn/protocols.php Protocol 4.1 states: “Develop, implement and use a national thesaurus for describing documentation relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and issues” We trust that the AIATSIS Thesauri will serve to assist in this task. -

0=AFRICAN Geosector

2= AUSTRALASIA geosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 175 25= CENDRAWASIH covers the "Cendrawasih" or "North Central New Guinea" Indonesia; Papua New Guinea 5 reference area, composed of sets not covered by any geozone phylozone or by the "Trans-New Guinea" hypothesis, within the wider reference area of the "Papuan" hypotheses; comprising 25 sets of languages (= 76 outer languages) spoken by communities in Australasia centered on Cendrawasih Bay & (Bird's Head) Peninsula, extending from the Halmahera Islands in the west to Central New Guinea in the east: 25-A TOBELO+ TERNATE 25-B MOI+KALABRA 25-C ABUN 25-D YACH+ BRAT 25-E MPUR 25-F BORAI+ HATAM 25-G MEAH+ MANTION 25-H AWERA+ SAPONI* 25-I YAWA+ TARAU 25-J TUNGGARE+ BAPU 25-K WAREMBORI 25-L PAUWI 25-M BURMESO 25-N MASSEP 25-O VANIMO+ WARAPU 25-P KWOMTARI+ FAS 25-Q BAIBAI+ NAI 25-R PYU 25-S YURI+ USARI 25-T YADE 25-U BUSA 25-V AMTO+ MUSAN 25-W AMA+ NIMO 25-X POROME+ KIBIRI 25-Y BIBASA* 25-A TOBELO+ TERNATE HALMAHERA-NORTH Latin script set 25-AA TOBELO+ SAHU chain 25-AAA TOBELO+ TUGUTIL net 25-AAA-a Tobelo Halmahera… Morotai islands; émigré > Raja Ampat islands Indonesia (Maluku); (Irian Jaya) 4 25-AAA-aa boëng Halmahera-N.… Morotai-N. islands; émigré > Raja Ampat islands Indonesia (Maluku); émigré> (Irian 4 Jaya) 25-AAA-ab heleworuru Halmahera-N. islands: Tobelo+ Wasile Indonesia (Maluku) 3 25-AAA-ac dodinga Halmahera-C. island: Pintatu Indonesia (Maluku) 3 25-AAA-b Tugutil+ Kusuri Halmahera-N. -

CLASSIFICATION of LAKE EYRE LANGUAGES Peter Austin 1

CLASSIFICATION OF LAKE EYRE LANGUAGES Peter Austin 1. Introduction1 The genetic classification of Australian Aboriginal languages has been a topic of heated debate among linguists over the past thirty years. The first attempt at a comprehensive classification for the whole continent was that proposed by O’Grady, Voegelin and Voegelin 1966 (see also O’Grady, Wurm and Hale 1966) using the lexicostatistical method. This classification claimed that all Australian languages were members of a single phylum and that there were twenty nine “phylic families” represented on the continent. One of these, Pama-Nyungan, covers the southern eight-tenths of the continent. A revised version of the classification was published by Wurm (1972) who reduced the number of families to twenty six (see also Wurm and Hattori 1982). Over the past ten years these classifications has been increasingly subjected to scrutiny. Dixon (1980:262ft) voiced strong criticism of the lexicostatistical classifications and claimed to have established a genetic classification (using traditional comparative-historical techniques) whereby all Australian languages, with the exception of Tiwi and Djingili, form a single genetic family and derive from a single ancestor proto-Australian (pA) (Dixon 1980:225). He argues that the distinction between Pama-Nyungan (PN) and non-Pama- Nyungan (nonPN) proposed by O’Grady, Hale and Wurm is not genetic but a typological and areal one. He says that “should not be inferred that PN is in any sense a genetic unity - that there was a proto-PN, as an early descendant of pA” (Dixon 1980:236). Dixon’s views have been challenged by Blake (1989, 1990) who compared verb pronominal prefix forms in a range of non-Pama-Nyungan languages and has been able to argue for reconstructing a prom-Northern system from which the attested nonPN systems evolve. -

Australian Phonemic Inventories Contributed to PHOIBLE 2.0 Essential Explanatory Notes

Australian phonemic inventories contributed to PHOIBLE 2.0 Essential explanatory notes Erich Round Jena, 2019 Contents 1. Comparative analysis of Australian phoneme inventories 2. Notes on individual languages 1. Comparative analysis of Australian phoneme inventories Phonemic analysis is a valuable prelude to cross-linguistic comparison. Nevertheless, phonemicization is not a deterministic process and linguistic practice is not uniform. This has certain consequences for the compilation and use of cross-linguistic summary datasets such as this one. The following notes are arranged by topic and highlight how these issues have been accommodated in the compilation of the Australian dataset. Labels The labeling of phonemes acts to group phonemes, implicitly or explicitly, into classes (e.g. ‘the stops’), yet phonemes may class together differently with respect to allophony vs phonological alternations vs phonotactics and even vs their history. Consequently, analysts are often forced to choose between multiple conceivable classifications, each of which captures only some of the facts. When they do so, one analyst’s criteria may differ from those of another. As a result, some cross-doculectal variation in phoneme labels may reflect more a variation among analysts’ necessary choices between multiple, defensible options, than empirical differences among languages. Where this appears to be the case, I have in some instances relabelled phonemes relative to source documents, to promote cross-linguistic comparability. For example, stops in languages with no contrast for voicing or fortition are labelled here with plain, voiceless IPA symbols, following widespread phonological practice. More cases are noted below. Segmentation The task of dividing words into segments can itself present challenges, since in this task phonemic analysis becomes interdependent with the analysis of phonotactics.