View a Copy of This Licence, Visit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Community Education About SARS-Cov-2 Infection in Uganda

HIS0010.1177/1178632920944167Health Services InsightsEchoru et al 944167research-article2020 Health Services Insights University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Volume 13: 1–7 © The Author(s) 2020 Community Education About SARS-CoV-2 Infection Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions in Uganda DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920944167 10.1177/1178632920944167 Isaac Echoru1 , Keneth Iceland Kasozi2 , Ibe Michael Usman3 , Irene Mukenya Mutuku1, Robinson Ssebuufu4 , Patricia Decanar Ajambo4, Fred Ssempijja3, Regan Mujinya3 , Kevin Matama5, Grace Henry Musoke6 , Emmanuel Tiyo Ayikobua7 , Herbert Izo Ninsiima1, Samuel Sunday Dare1,2, Ejike Daniel Eze1,2, Edmund Eriya Bukenya1, Grace Keyune Nambatya8, Ewan MacLeod2 and Susan Christina Welburn2,9 1School of Medicine, Kabale University, Kabale, Uganda. 2Infection Medicine, Deanery of Biomedical Sciences, and College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. 3Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, Kampala International University Western, Bushenyi, Uganda. 4Faculty of Clinical Medicine and Dentistry, Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Bushenyi, Uganda. 5School of Pharmacy, Kampala International University Western Campus, Bushenyi, Uganda. 6Faculty of Science and Technology, Cavendish University, Kampala, Uganda. 7School of Health Sciences, Soroti University, Soroti, Uganda. 8Directorate of Research, Natural Chemotherapeutics Research Institute, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda. 9Zhejiang University-University of Edinburgh -

FY 2018/19 Vote:553 Soroti District

LG WorkPlan Vote:553 Soroti District FY 2018/19 Foreword Soroti District Local Government Draft Budget for FY 2018/19 provides the Local Government Decision Makers with the basis for informed decision making. It also provides the Centre with the information needed to ensure that the national Policies, Priorities and Sector Grant Ceilings are being observed. It also acts as a Tool for linking the Development Plan, Annual Workplans as well as the Budget for purposes of ensuring consistency in the Planning function This draft budget ZDVDUHVXOWRIFRQVXOWDWLRQZLWKVHYHUDOVWDNHKROGHUVLQFOXGLQJ6XE&RXQW\2IILFLDOVDQG/RFDO&RXQFLORUVDW6XE&RXQW\DQG'LVWULFWDQGLQSXWIURPGHYHORSPHQW partners around the District. This budget is based on the theme for NDPII which is strengthening Uganda's competitiveness for sustainable wealth creation, employment and inclusive growth , productivity tourism development, oil and gas, mineral development, human capital development and infrastructure. The District has prioritized infrastructure development in areas of water, road, Health and Education. With regards to employment creation the district hopes that the funds from </3 <RXWK/LYHOLKRRG3URJUDPPHXQGHU0*/6' ZLOOJRDORQJZD\ZLWKUHJDUGVWR+XPDQFDSLWDOGHYHORSPHQWWKHGLVWULFWZLOOFRQWLQXHWRLPSURYHWKH quality of health care development and market linkage through empowering young entrepreneurs and provision of market information. We will continue to work ZLWKWKRVHGHYHORSPHQWSDUWQHUVWKDWDFFHSWWKHWHUPVDQGFRQGLWLRQVRIWKH0R8VWKDWWKHGLVWULFWXVHVP\WKDQNVJRWRDOOWKRVHZKRSDUWLFLSDWHGLQHYROYLQJWKLV Local Government Budget Frame work paper. I wish to extent my sincere gratitude to the Ministry of Finance Planning and Economic Development and Local Government Finance Commission for coming with the new PBS reporting and budgeting Format that has improved the budgeting process. My appreciation goes to the Sub County and District Council, I also need to thank the Technical Staff who were at the forefront of this work particular the budget Desk. -

Establishment of Soroti University) Instrument, 2015

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT No. 22 16th July, 2015. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT to The Uganda Gazette No. 39, Volume CVIII, dated 16th July, 2015. Printed by UPPC, Entebbe, by Order of the Government. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2015 No. 34. The Universities and Other Tertiary Institutions (Establishment of Soroti University) Instrument, 2015. (Under section 22(1) of the Universities and Other Tertiary Institutions Act, 2001). IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred upon the Minister responsible for Education by section 22(1), 24(1) and 25 of the Universities and Other Tertiary Institutions Act, 2001 and on the recommendation of the National Council for Higher Education, this Instrument is made this 8th day of July, 2015. 1. Title. This Instrument may be cited as the Universities and Other Tertiary Institutions (Establishment of a Soroti University) Instrument, 2015. 2. Establishment of Soroti University. (1) There is established a public University to be known as the Soroti University. (2) The headquarters of the University shall be located in Soroti District in Eastern Uganda. 3. Objects of the University. The objects for which the University is established are— (a) to be the standard of excellence and innovation for societal transformation; 151 (b) to be a leader in integrating scholarship and practice; (c) to serve societal needs and to foster social and economic development; (d) to be global in perspective, organization and action; (e) to engage staff and students in creative and rewarding learning so as to enhance economic and societal development in Uganda and beyond; and (f) to assist local communities and to build their capacity for socio-economic enhancement. -

Soroti-University-Government-Sponsorship-National-Merit-2020-2021-F

22ND/JUNE/2020 GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2020/2021 ACADEMIC YEAR THE FOLLOWING HAVE BEEN ADMITTED TO THE FOLLOWING PROGRAMME BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY COURSE CODE SOM INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0027/621 MUTAI Levi 2019 M U 61 KIIRA COLLEGE, BUTIKI 49.6 2 U1076/515 KAJUMBA Ronald 2019 M U 55 HENRY KASULE M.C., KAKIRI 47.8 3 U2511/501 SSEMAGANDA Hakim 2019 M U 42 KASAWO ISLAMIC INSTITUTE 47.7 4 U0334/597 OKELLO Jorem 2019 M U 53 UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 47 5 U0097/562 MUKISA Joshua 2019 M U 81 ST.KALEMBA SECONDARY SCHOOL 46.8 6 U0027/629 MWESIGWA David 2019 M U 17 KIIRA COLLEGE, BUTIKI 46.8 7 U0027/537 GAHUUTU Buraida 2019 M U 11 KIIRA COLLEGE, BUTIKI 46.7 8 U1224/984 TURINAWE Boaz 2019 M U 46 ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 46.7 9 U0024/542 EDOTU Dan 2019 M U 111 SOROTI SECONDARY SCHOOL 46.7 10 U0505/532 KAWOOYA Reagan Jimmy 2019 M U 55 KITENDE S S 46.7 11 U0685/563 MUGUMYA Isaac 2019 M U 41 MITYANA MODERN SS 46.7 12 U0184/515 SSEMUJJU Edsone 2019 M U 40 ST.BALIKUDDEMBE SS MITALA MARIA 46.7 13 U1923/632 ONAP Oscar 2019 M U 94 KIGUMBA INTENSIVE S.S 46.7 14 U1354/501 AKOL Benard 2019 M U 67 MERRYLAND HIGH SCHOOL 46.7 15 U2236/511 KULE Ziste 2019 M U 21 ST.MARY'S COLLEGE, LUGAZI 46.7 16 U1121/538 NALUMAGA Justine 2019 F U 32 WOBULENZI HIGH SCHOOL 45.4 17 U1828/561 NABAASA Racheal 2019 F U 46 STANDARD COLLEGE NTUNGAMO 45.3 18 U1979/551 NANTEGE Phionah 2019 F U 32 GAYAZA CAMBRIDGE COLLEGE 45.3 19 U1873/593 KANYESIGYE Loyce 2019 F U 06 ST. -

BMAU Briefing Paper 24/18: Funding of Public Universities in Uganda

BMAU BRIEFING PAPER (24/18) JUNE 2018 Funding of Public Universities in Uganda: what are the issues? Overview Key Issues The second National Development Plan (NDP II) notes 1. The increase in number of public universities has that public funding to higher education remains at amplified the burden of funding from Ug shs 167.94 0.3% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) which is billion in FY 2012/13 to Ug shs 606.09 billion during below the recommended share of at least 1%. The FY 2017/18. sources of funds for public universities in Uganda are 2. Public universities are not funded sufficiently to cover public, private, and external funding as well as the cost of inputs in order to offer quality education. For the last five years, actual releases have been Internally Generated Funds (IGFs). lower than approved budgets. The major source of funding for university education is 3. Physical infrastructure in public universities has not private funding (parents and individuals). This is grown in tandem with enrollments. followed by government/public funding, external 4. The budgets for non-tax revenue (NTR) in public funding and IGFs respectively. This paper examines universities have been increasing. Public universities public funding of these universities and identifies some are increasingly depending on collection from NTR to deliver the education service. of the critical persistent issues affecting the institutions 5. Funding for research and publication has remained over the period FY 2012/13 to FY 2017/18 that require very low in public universities yet it is their core urgent attention going forward. -

Institutional Design and Utilisation of Evaluation Results in Uganda`S Public Universities: a Case Study of Kyambogo University

INSTITUTIONAL DESIGN AND UTILISATION OF EVALUATION RESULTS IN UGANDA`S PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES: A CASE STUDY OF KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY BY JAMES KABUYE SEP15/MME/0440U A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF A MASTER’S IN MONITORING AND EVALUATION OF UGANDA TECHNOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT UNIVERSITY (UTAMU). AUGUST, 2016 i DECLARATION I, James Kabuye, declare to the best of my knowledge that this work is original and it has not been published and/or submitted for any other degree award to any other University before. Signed: …………………………………………………….. Date ............................................. i APPROVAL This is to certify that this Dissertation titled “ Institutional Design and Utilisation of Evaluation Results in Uganda`s Public Universities: A Case Study of Kyambogo University” was submitted with my approval as the Supervisor: Signature……………………………………………….Date...................................................... Professor Benon C. Basheka, PhD ii DEDICATION This Dissertation is dedicated to my children; Nethaneel and Joanna. iii ACKNOWLEGEMENTS I am so very grateful to God for enabling me to complete a Master’s of Monitoring and Evaluation of UTAMU. I am highly thankful to my Dissertation Supervisor; Professor Benon Basheka, w h o untiringly supervised and guided me at every stage of this Dissertation, more so, by always responding very timely, every time I called. Words of gratitude are owed to my mother for her support, encouragement and material assistance given to me from childhood; my dear wife, Esther and our children: Joanna and Nethaneel as well as Diana; and all my brothers and sisters. In a special way, acknowledgement is made to my elder sister, Joyce, who intervened at the right time in the course of my education. -

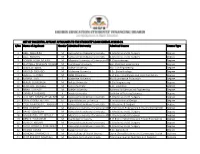

LIST of SUCCESFUL APPEALS' APPLICANTS to the STUDENTS' LOAN SCHEME AY2020-21 S/No Name of Applicant Gender Admitted University Admitted Course Course Type

LIST OF SUCCESFUL APPEALS' APPLICANTS TO THE STUDENTS' LOAN SCHEME AY2020-21 S/No Name of Applicant Gender Admitted University Admitted Course Course Type 1 ABEL NAHURIRA M Kampala International University B. Medicine and B. Surgery Degree 2 ABEL NSIIMIRE M Kampala International University B. Medicine and B. Surgery Degree 3 ADRIAN NOAH MUKISA M Mbarara University of Science and TechnologyB. Physiotherapy Degree 4 ALEX NALE WILLIAMS NUWAGABAM Kyambogo University BSc. Chemical Engineering Degree 5 ANDREW BBIRA M Ndejje University BSc. Civil Engineering Degree 6 ARNOLD SSEGABO M Makerere University B.Sc. Biotechnology Degree 7 ASAHEL TENYWA M ISBAT University B of Eng in Electronics and Communication Degree 8 BARBRA AYO F Makerere University BSc Quantitative Economics Degree 9 BENUS GUMISIRIZA M Ndejje University B Civil Engineering Degree 10 BONIFACE OGWELA M Gulu University B.Sc. Education Degree 11 BRIAN LUWAGA M Ndejje University Bachelor of Mechanical Engineering Degree 12 CAMILLA NABWIRE F Soroti University Bachelor of Nursing Sciences Degree 13 COLLINES MWESIGYE MICHAEL M Kampala International University B. Medicine and B. Surgery Degree 14 CRAY AZOORA HILLARY M Uganda Martyrs University B. environmental Design Degree 15 CYLEEN FAVOURITE KABIITO F Kampala International University B. Medicine & Surgery Degree 16 DAN ASIIMWE M Mbarara University of Science and TechnologyB. Petroleum Engineering & Environmental Mgt Degree 17 DAVID SSEMBUYA M Kampala International University B. Medicine and B. Surgery Degree 18 DEOGRATIAS DELAFRIQUE M Mbarara University of Science and TechnologyB. Pharmaceutical Sciences Degree 19 DERICK TUMUSIIME M Kyambogo University B of Eng in Automotive and Power Engineering Degree 20 DERRICK KIGENYI M Kampala International University B. -

Report of the Auditor General on the Financial Statements of Soroti University for the Year Ended 30Th June 2018

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF SOROTI UNIVERSITY FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2018 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................ 2 Opinion .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Basis of Opinion .................................................................................................................................... 3 Key Audit Matters ................................................................................................................................. 3 Implementation of Budget approved by Parliament .......................................................... 4 Other Matter ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Provision of Legal Services to the University ...................................................................... 5 Delayed Enrolment of Students ............................................................................................ 6 Occupancy of University Land ............................................................................................... 7 Other Information ............................................................................................................................... -

OFFICE of the UNIVERSITY SECRETARY JOB VACANCIES Soroti University Is a Public University in Uganda Located in Soroti City, Eastern Uganda Along Soroti-Moroto Road

OFFICE OF THE UNIVERSITY SECRETARY JOB VACANCIES Soroti University is a Public University in Uganda located in Soroti City, Eastern Uganda along Soroti-Moroto Road. Applications are invited from suitably qualified candidates to fill the vacancies listed below. UNIT POSITION VACANCIES AREA OF SPECIALIZATION School of Assistant 1 Communication Engineering Engineering Lecturer and Technology Assistant 1 Electrical Engineering Lecturer Assistant 1 Electronic Engineering Lecturer School of Senior Lecturer 1 Microbiology Health Senior Lecturer 1 Physiology Sciences Lecturer 1 Physiology Assistant 1 Physiology Lecturer Lecturer 1 Pathology Lecturer 1 Medical-Surgical Nursing Lecturer 1 Anatomy Assistant 1 Anatomy Lecturer Lecturer 2 Biochemistry Assistant 1 Biochemistry Lecturer Technician 1 Pathology Position Vacancies Department Page 1 of 21 Advert for Soroti University March 2021 Recruitment Central Director of 1 Directorate of Human Resource Administration Human Resource Civil Engineer 1 Estates and Works Personal 1 Office of the Vice Chancellor Assistant Six (6) copies of letter of application together with an up-to-date Curriculum vitae, a photocopy of the National Identity card or Passport biodata page, certified copies of academic and professional qualifications, and letters of reference in one (1) PDF file should be addressed to The University Secretary, Soroti University, P.O Box 211, Soroti Uganda OR sent by email to [email protected] not later than 6th April 2021. All applications should provide names, address, telephone contacts and e-mails of two referees one of whom should be the previous or current employer or supervisor. A detailed job advert and description is available on Soroti University website www.sun.ac.ug. -

RECOGNISED TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES No Insititutions Name and Address 1 Makerere University P.O. Box 7062, Kamp

RECOGNISED TERTIARY INSTITUTIONS PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES No Insititutions Name and Address 1 Makerere University P.O. Box 7062, Kampala www.muk.ac.ug 2 Mbarara University of Science and Technology P.O. Box 1410, Mbarara www.must.ac.ug 3 Gulu University P.O. Box 166, Gulu www.gu.ac.ug/ 4 Kyambogo University P.O. Box 1, Kyambogo www.kyu.ac.ug 5 Busitema University P.O. Box 236, Tororo htp://busitema.ac.ug/ 6 Muni University P.O.Box 725, Arua Email: [email protected] www.muni.ac.ug 7 Kabale University P.O. Box 317, Kabale, Kikungiri 8 Lira University Plot 1162, Ayere Barapwo P.O.Box 1035, Lira Tel: 0471660714 8 Soroti University Plot 50 & 51 Arapai P.O.Box 211, Soroi Tel: 0454461605 www.su.ac.ug PUBLIC UNIVERSITY COLLEGES No Insituions Name and Address 1 Makerere University Business School P.O. Box 7062 Kampala, Uganda. Tel: +256-41- 32752/530231/5302232. Website: htp://mak.ac.ug. Fax: +256 -41 533640/ 541068. 2 Makerere University College of Health Sciences P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://chs.mak.ac.ug/ 3 Makerere University College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://sas.mak.ac.ug/ 4 Makerere University College of Business and Management Science P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://bams.mak.ac.ug 4 Makerere University College of Compuing and Informaion Sciences P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://cis.mak.ac.ug 5 Makerere University College of Educaion and External Studies P.O. Box 7062, Kampala htp://cees.mak.ac.ug 6 Makerere University College of Engineering, Design, Art & Technology P.O. -

Top Management Team International Orientation, Internal Environment, Organizational Characteristics and Internationalization of Universities in Uganda

TOP MANAGEMENT TEAM INTERNATIONAL ORIENTATION, INTERNAL ENVIRONMENT, ORGANIZATIONAL CHARACTERISTICS AND INTERNATIONALIZATION OF UNIVERSITIES IN UGANDA DENNIS NUWAGABA A THESIS PRESENTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION SCHOOL OF BUSINESS - UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2018 DECLARATION ii COPYRIGHT All rights reserved; for this reason, no part of this work can be used or reproduced in any form by any means, or stored in any database or retrieval system, without explicit prior written permission from the author or University of Nairobi (UON) on that behalf except in the case of acknowledged quotations embodied in reviews, articles and research papers. Reproducing any part of this work in softcopy, hardcopy or keeping it in any retrieval format for any purpose other than personal use is a violation of the Kenyan, Ugandan and international laws. ©DennisNuwagaba2018 Dennis Nuwagaba iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank God who has brought me this far on this academic journey. Jesus Christ, my Lord and Saviour, it is through you that this journey was started and it is through you that it is coming to an end. I will always praise you. To my supervisors; Dr. John Yabs, Dr. Kennedy Ogollah and Prof. Gituro Wainaina, thank you for the professional and technical guidance you have given me in the process of doing this study. I owe this study to you. Thank you for the availability and accessibility whenever I requested to see you. I would like to pay my tribute and gratitude to my employer, Makerere University Business School (MUBS), under the leadership of the Principal, Prof. -

Aide-Mémoire ISA/M.01/WD.02 23Rd-28Th June, 2019 Kampala, Uganda (Confidential) Aide-Mémoire for Expert Level Visit To

Aide-Mémoire ISA/M.01/WD.02 23rd-28th June, 2019 Kampala, Uganda (Confidential) Aide-Mémoire for Expert Level Visit to Uganda for Pre-Feasibility Study of Solar Pumps, Rooftop and Mini-Grid Projects by International Solar Alliance Secretariat held from 24-28 June, 2019. Venue: Kampala, Uganda ISA/M.01/WD.02 Aide-Mémoire Expert Level Visit for Pre-Feasibility Study of Solar Pumps, Rooftop and Mini-Grid Projects by International Solar Alliance Secretariat June 24th, 2019 to June 28th, 2019 A. Background/ Introduction of the Mission During 24th June, 2019 to 28th June, 2019, ISA led Expert team visited Republic of Uganda, hereafter referred to as the Host Country, for pre-feasibility study of demand submitted to ISA Secretariat for Solar Pumping Systems under the call for Expression of Interest (EoI) from ISA vide number No. 23/61/2017/NFP/R&D. This Aide-Memoire (AM) summarizes the outcome of stakeholders’ meetings with the expert team (as detailed in the Annex-1 to this document) as well as agreements reached therein. The AM was discussed in the wrap-up meeting on 28th June, 2019, chaired by ……….. As agreed, this AM shall be a point of reference for future planning as well as implementation of the programme. B. Overall Status of the Programmes 1. Programme for Solar Water Pumping Systems The Host Country has submitted a demand for 30,000 Solar Pumping Systems against the call for Expression of Interest from ISA. In response to the demand aggregation submitted by the Government of the Host Country, ISA Secretariat has engaged consultants from KPMG India for feasibility study of the projected demand as well as analysis of institutional capacity of stakeholders in the project and division of responsibility thereof.