University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Community Education About SARS-Cov-2 Infection in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr-Eton-Marus-CV.Pdf

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME Eton Marus (PhD) DATE OF BIRTH Septembers 28th 1978 ADDRESS Kabale University, Uganda Box 317 Kabale 256772880149/256701304416 [email protected]/[email protected] PROFESSIONAL Finance/Accounts, Business, Marketing and Monitoring and Evaluation AREAS ACADEMIC YEARS INSTITUTION QUALIFICATIONS QUALIFICATIONS 2015-2018 Nkumba University PhD Business Administration (Finance) 2016-2017 Uganda Management Post Graduate Diploma In Institute-Kampala Monitoring and Evaluation 2010-2012 Cavendish University Masters in Business Administration 2009-2010 Gulu University Post Graduate Diploma in Financial Management 2002-2006 Makerere University Bachelor of Commerce 1998-2001 Makerere University Higher Diploma In Business School Marketing OTHER Grant and Proposal Writing and Management. (ACRA) Mbarara TRAININGS University of Science and Technology July 2019 Programme Skills Development (Assessing Academic and Professional Programmes, Uganda National Council of Higher Education, Kampala 2019. Researcher Connect Professional Development for Researchers (Proposal writings skills, Resource mobilization, Academic Collaborations, Networking, Grants Management and Persuasive Proposal writing. British Council Kampala 2019. Post Graduate Certificate in Monitoring and Evaluation, Makerere University 2014. Post Graduate Certificate in Administrative Law Makerere University 2013 Post Graduate Certificate in Procurement and Contract Management Uganda Management Institute-Kampala 2013 Post Graduate Certificate in Training of Trainers, -

FY 2018/19 Vote:553 Soroti District

LG WorkPlan Vote:553 Soroti District FY 2018/19 Foreword Soroti District Local Government Draft Budget for FY 2018/19 provides the Local Government Decision Makers with the basis for informed decision making. It also provides the Centre with the information needed to ensure that the national Policies, Priorities and Sector Grant Ceilings are being observed. It also acts as a Tool for linking the Development Plan, Annual Workplans as well as the Budget for purposes of ensuring consistency in the Planning function This draft budget ZDVDUHVXOWRIFRQVXOWDWLRQZLWKVHYHUDOVWDNHKROGHUVLQFOXGLQJ6XE&RXQW\2IILFLDOVDQG/RFDO&RXQFLORUVDW6XE&RXQW\DQG'LVWULFWDQGLQSXWIURPGHYHORSPHQW partners around the District. This budget is based on the theme for NDPII which is strengthening Uganda's competitiveness for sustainable wealth creation, employment and inclusive growth , productivity tourism development, oil and gas, mineral development, human capital development and infrastructure. The District has prioritized infrastructure development in areas of water, road, Health and Education. With regards to employment creation the district hopes that the funds from </3 <RXWK/LYHOLKRRG3URJUDPPHXQGHU0*/6' ZLOOJRDORQJZD\ZLWKUHJDUGVWR+XPDQFDSLWDOGHYHORSPHQWWKHGLVWULFWZLOOFRQWLQXHWRLPSURYHWKH quality of health care development and market linkage through empowering young entrepreneurs and provision of market information. We will continue to work ZLWKWKRVHGHYHORSPHQWSDUWQHUVWKDWDFFHSWWKHWHUPVDQGFRQGLWLRQVRIWKH0R8VWKDWWKHGLVWULFWXVHVP\WKDQNVJRWRDOOWKRVHZKRSDUWLFLSDWHGLQHYROYLQJWKLV Local Government Budget Frame work paper. I wish to extent my sincere gratitude to the Ministry of Finance Planning and Economic Development and Local Government Finance Commission for coming with the new PBS reporting and budgeting Format that has improved the budgeting process. My appreciation goes to the Sub County and District Council, I also need to thank the Technical Staff who were at the forefront of this work particular the budget Desk. -

Rule by Law: Discriminatory Legislation and Legitimized Abuses in Uganda

RULE BY LAW DIscRImInAtORy legIslAtIOn AnD legItImIzeD Abuses In ugAnDA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: AFR 59/06/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Ugandan activists demonstrate in Kampala on 26 February 2014 against the Anti-Pornography Act. © Isaac Kasamani amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. Introduction -

Uganda at 50: the Past, the Present and the Future

UGANDA AT 50: THE PAST, THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue Organised by ACODE, 93.3 Kfm and NTV Uganda at the Sheraton Hotel - Kampala – October 3, 2012 Naomi Kabarungi-Wabyona ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No. 17, 2013 UGANDA AT 50: THE PAST, THE PRESENT AND THE FUTURE A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue Organised by ACODE, 93.3 Kfm and NTV Uganda at the Sheraton Hotel - Kampala – October 3, 2012 Naomi Kabarungi-Wabyona ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No. 17, 2013 ii A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue 2012 Published by ACODE P.O. Box 29836, Kampala - UGANDA Email: [email protected], [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Kabarungi, N. (2013). Uganda at 50: The Past, the Present and the Future. A Synthesis Report of the Proceedings of the “Uganda @ 50 in Four Hours” Dialogue. ACODE Policy Dialogue Report Series, No.17, 2013. Kampala. © ACODE 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without prior permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purpose or for purposes of informing public policy is exempted from this restriction. ISBN 978 9970 34 009 5 Cover Photo: A Cross section of participants attending the Uganda @50 in 4 Hours Dialogue held on October 3, 2012 at Sheraton Hotel in Kampala. -

Chased Away and Left to Die

Chased Away and Left to Die How a National Security Approach to Uganda’s National Digital ID Has Led to Wholesale Exclusion of Women and Older Persons ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Publication date: June 8, 2021 Cover photo taken by ISER. An elderly woman having her biometric and biographic details captured by Centenary Bank at a distribution point for the Senior Citizens’ Grant in Kayunga District. Consent was obtained to use this image in our report, advocacy, and associated communications material. Copyright © 2021 by the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, Initiative for Social and Economic Rights, and Unwanted Witness. All rights reserved. Center for Human Rights and Global Justice New York University School of Law Wilf Hall, 139 MacDougal Street New York, New York 10012 United States of America This report does not necessarily reflect the views of NYU School of Law. Initiative for Social and Economic Rights Plot 60 Valley Drive, Ministers Village Ntinda – Kampala Post Box: 73646, Kampala, Uganda Unwanted Witness Plot 41, Gaddafi Road Opp Law Development Centre Clock Tower Post Box: 71314, Kampala, Uganda 2 Chased Away and Left to Die ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report is a joint publication by the Digital Welfare State and Human Rights Project at the Center for Human Rights and Global Justice (CHRGJ) based at NYU School of Law in New York City, United States of America, the Initiative for Social and Economic Rights (ISER) and Unwanted Witness (UW), both based in Kampala, Uganda. The report is based on joint research undertaken between November 2020 and May 2021. Work on the report was made possible thanks to support from Omidyar Network and the Open Society Foundations. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Joy Constance Kwesiga (March 2020)

CURRICULUM VITAE Professor Joy Constance Kwesiga (March 2020) A. PERSONAL INFORMATION: NAME: Joy Constance Kwesiga DATE OF BIRTH: 03rd May 1943 SEX: Female NATIONALITY: Ugandan CONTACT: Kabale University P. O. Box 317 Kabale, Uganda. Tel: +256-772485267 / +256-751812325 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] or [email protected] B. BRIEF BIO FOR JOY KWESIGA Professor Joy Constance Kwesiga, Ph.D (London), is an experienced academician, University Administrator and Social Development Analyst and a renowned gender and Women advocate and mentor. She has had an enviable privilege of combining academic work with women’s rights activist work. She has been a Professor of Gender Studies and the Vice Chancellor of Kabale University since November 2005 to date. She oversaw the transformation of Kabale University from a Private Community University to a Public University (since 2015). Even when Kabale University was a private University, she effectively steered it to attain an Operating Licence in 2005, and a University Charter in 2014. Previously, Professor Kwesiga served at various levels as a University Administrator at Makerere University, rising from the ranks to the level of Deputy Academic Registrar. She then switched to the academic arena, serving as the Head of the Department of Women and Gender Studies, and later became the Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Makerere University. Professor Kwesiga was the founding Head of the Gender Mainstreaming Division of the Academic Registrar’s Department at Makerere University. The goal of the Gender Mainstreaming Programme is to make Makerere University an all-inclusive institution. Professor Kwesiga was able to lay its foundation. -

Undergraduate Private Admissions 2020/2021 Academic Year

MBARARA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY OFFICE OF THE ACADEMIC REGISTRAR P.O. Box 1410, MBARARA-UGANDA Telephone: +256-485-660584, +256-414-668971 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Web: www.must.ac.ug UNDERGRADUATE PRIVATE ADMISSIONS 2020/2021 ACADEMIC YEAR The following have been admitted to the different programmes as below for the 2020/2021 academic year. Admission letters shall be sent by email to applicants who have paid a NON-REFUNDABLE TUITION FEES DEPOSIT of Shs. 50,000=. Visit www.must.ac.ug for instructions on how to pay or contact us by email [email protected] or WhatsApp us on +256-786-706490. BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN COMPUTER ENGINEERING SN NAME GENDER NATIONALITY DISTRICT ALEVEL_INDEX YEAR WEIGHT 1 BATAMYE ABDUL M Ugandan BUIKWE U1609/635 2019 47.1 2 BONGO JOSHUA M Ugandan APAC U2060/581 2019 44.2 3 KIA JANET F Ugandan ALEBTONG U1923/610 2019 43.7 4 NSHEKANABO MARIUS M Ugandan SHEEMA U1063/563 2019 41.3 5 BINTO NAOMI F Ugandan MUKONO U2583/568 2019 40.7 6 BWAMBALE ROBERT SEMAKULA M Ugandan KASESE U3231/514 2019 31.5 7 MUTEBI JONATHAN M Ugandan WAKISO U0053/823 2019 31.2 8 ARINAITWE JULIUS M Ugandan MBARARA U1495/554 2017 31.1 9 ATWIINE SAGIUS M Ugandan NTUNGAMO U0946/572 2019 28.0 10 KISAKYE JULIUS M Ugandan IGANGA U0027/564 2019 27.6 11 MUKWATANISE ALBERT M Ugandan ISINGIRO U0334/692 2019 27.6 12 MATEGE DERICK M Ugandan KAMULI U2877/614 2012 27.1 13 MUHUMUZA JOSEPH M Ugandan KISORO U0080/566 2019 25.2 14 MWEBESA TREVOR M Ugandan NTUNGAMO U0053/827 2019 25.2 15 KAANYI JANE PATIENCE F Ugandan KIBUKU U0065/586 -

Download International Students' Brochure

Brief Inf ormation Brochure - for - International Students Kabale University. P.O Box 317, Kabale - Uganda Address: Plot 364 Block 3 Kikungiri Hill, Kabale Municipality +256 7 82860259 | +2567486426463 inf [email protected] | [email protected] Brief information Brochure for International Students Experience Education in the Pearl of Africa. Introduction No matter where you come from or what you would like to do when you graduate, Kabale University experience will challenge, inspire, develop and support you. Through a combination of excellent teaching, a rich and varied campus life and a cultured community, you'll have the experience of a lifetime. The University is a home away from home to many international students and we always have nice warm people welcoming you from all around the world. We are sure and confident that life at Kabale University (KAB) is pretty relaxed and you will love the ambiance other students and staff accord to you. Background Information Kabale University is located on Plot 364 Block 3 Kikungiri Hill, in Kabale Municipality, about a kilometre off Kabale-Katuna-Kigali Highway. The Main Campus sits on 50 acres of land. The University can be accessed via Mukombe Road, which connects the Kikungiri Campus to the Highway. An additional Campus is located on Plots 66-76 in Nyabikoni Parish in the Central Division of Kabale Municipality comprising of 3 acres. This houses the Faculty of Engineering, Technology, Applied Design and Fine Art. Kabale University School of Medicine is partially housed on Makanga Hill, in the Kabale Regional Referral Hospital next to the headquarters of Kabale District Local Government. -

Presidential Intervention and the Changing 'Politics of Survival' in Kampala's Informal Economy

Tom Goodfellow and Kristof Titeca Presidential intervention and the changing ‘politics of survival’ in Kampala’s informal economy Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Goodfellow, Tom and Titeca, Kristof (2012) Presidential intervention and the changing ‘politics of survival’ in Kampala’s informal economy. Cities, 29 (4). pp. 264-270. ISSN 0264-2751 DOI: 10.1016/j.cities.2012.02.004 © 2012 Elsevier This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/39762 Available in LSE Research Online: May 2012 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final manuscript accepted version of the journal article, incorporating any revisions agreed during the peer review process. Some differences between this version and the published version may remain. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Presidential intervention and the changing ‘politics of survival’ in Kampala’s informal economy Published in Cities: The International -

Ccuurrrriiccuulluumm Vviittaaee

CCUURRRRIICCUULLUUMM VVIITTAAEE BENON C. BASHEKA (PhD, FCIPS) PROFESSOR OF GOVERNANCE AND DEPUTY VICE CHANCELLOR- ACADEMIC AFFAIRS Email: [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Mobile: +256-782-459-354 Personal Website:http://benonbasheka.com Management Consulting Website: http://www.radixconsults.com/ 1. SUMMARY Basheka is a Professor of Governance in the Department of Governance and the 1st Deputy Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs at Kabale University. Kabale University is a Government University located in South Western part of Uganda. Professor Basheka also holds the position of an Extra-Ordinary Professor at the School of Business and Governance of the North-West University (NWS) Business School in South Africa (January 2020-December 2023). He is also a visiting Professor and Research fellow at the School of Public Management, Governance and Public Policy in the College of Economics and Management Sciences at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa. Professor Basheka is an accomplished scholar, researcher, teacher, management, administration, governance and leadership specialist and consultant. He has authored more than 80 articles in internationally accredited journals, more than 15 books and book chapters and a number of reports and conference proceedings. As of 25thJuly, 2021, his google citation index stood at 1694 citations with an h-index of 20 and an i10-index of 39. Professor Basheka cherishes a forward-thinking approach to issues, believes in team-based leadership competences, results-oriented, believes merit-based systems and principles and always aspires to foster innovative solutions to problems. Prof Basheka has a multidisciplinary academic background with two PhDs, two Master’s Degrees, Two postgraduate Diplomas and One Bachelor’s Degree. -

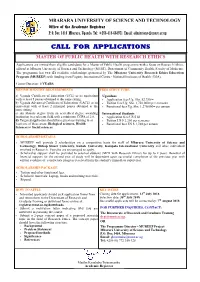

Call for Applications Master of Public Health with Research Ethics

MBARARA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Office of the Academic Registrar P. O. Box 1410 Mbarara, Uganda Tel: +256-414-668971 Email: [email protected] CALL FOR APPLICATIONS MASTER OF PUBLIC HEALTH WITH RESEARCH ETHICS Applications are invited from eligible candidates for a Master of Public Health programme with a focus on Research Ethics, offered at Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST), Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine. The programme has two (2) available scholarships sponsored by The Mbarara University Research Ethics Education Program (MUREEP) with funding from Fogarty International Centre - National Institutes of Health (USA). Course Duration: 2 YEARS MINIMUM ENTRY REQUIREMENTS FEES STRUCTURE a) Uganda Certificate of Education (UCE) or its equivalent Ugandans with at least 5 passes obtained at the same sitting. Application fees Ug. Shs. 52,750/= b) Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education (UACE) or its Tuition fees Ug. Shs. 1,750,000= per semester equivalent with at least 2 principal passes obtained at the Functional fees Ug. Shs. 1,270,000= per annum same sitting. c) An Honors degree from an accredited degree awarding International Students institution in a relevant field with a minimum CGPA of 2.8. Application fees US $ 50 d) Targeted applicants should have previous training in at Tuition US $ 2,250 per semester least one of these areas: Biological sciences, Health Functional fees US $ 1,740 per annum Sciences or Social sciences. SCHOLARSHIP DETAILS MUREEP will provide 2 scholarships on a competitive basis for staff of Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Bishop Stuart University, Kabale University, Kampala International University and other individuals involved in Research. -

List of Abbreviations

HRNJ - Uganda Human Rights Network for Journalists-Uganda (HRNJ-Uganda) Press Freedom Index Report April 2011 2 HRNJ - Uganda Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Background .............................................................................................. 7 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 7 Elections and Media .............................................................................................. 7 Research Objective ............................................................................................... 8 Methodology ......................................................................................................... 8 Quality check ......................................................................................................... 8 Limitations ............................................................................................................. 9 Part II: Media freedom during national elections in Uganda ................................ 11 Media as a campaign tool ................................................................................... 11 Role of regulatory bodies ................................................................................... 12 Media self censorship ......................................................................................... 14 Censorship of social media