Shared Governance in Public Universities in Uganda: Current Concerns and Directions for Reform Lazarus Nabaho

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Community Education About SARS-Cov-2 Infection in Uganda

HIS0010.1177/1178632920944167Health Services InsightsEchoru et al 944167research-article2020 Health Services Insights University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Volume 13: 1–7 © The Author(s) 2020 Community Education About SARS-CoV-2 Infection Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions in Uganda DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920944167 10.1177/1178632920944167 Isaac Echoru1 , Keneth Iceland Kasozi2 , Ibe Michael Usman3 , Irene Mukenya Mutuku1, Robinson Ssebuufu4 , Patricia Decanar Ajambo4, Fred Ssempijja3, Regan Mujinya3 , Kevin Matama5, Grace Henry Musoke6 , Emmanuel Tiyo Ayikobua7 , Herbert Izo Ninsiima1, Samuel Sunday Dare1,2, Ejike Daniel Eze1,2, Edmund Eriya Bukenya1, Grace Keyune Nambatya8, Ewan MacLeod2 and Susan Christina Welburn2,9 1School of Medicine, Kabale University, Kabale, Uganda. 2Infection Medicine, Deanery of Biomedical Sciences, and College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. 3Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, Kampala International University Western, Bushenyi, Uganda. 4Faculty of Clinical Medicine and Dentistry, Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Bushenyi, Uganda. 5School of Pharmacy, Kampala International University Western Campus, Bushenyi, Uganda. 6Faculty of Science and Technology, Cavendish University, Kampala, Uganda. 7School of Health Sciences, Soroti University, Soroti, Uganda. 8Directorate of Research, Natural Chemotherapeutics Research Institute, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda. 9Zhejiang University-University of Edinburgh -

Vote:127 Muni University

Education Vote Budget Framework Paper FY 2020/21 Vote:127 Muni University V1: Vote Overview (i) Snapshot of Medium Term Budget Allocations Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures Billion Uganda Shillings FY2018/19 FY2019/20 FY2020/21 MTEF Budget Projections Approved Spent by Proposed 2021/22 2022/23 2023/24 2024/25 Outturn Budget End Sep Budget Recurrent Wage 6.828 9.207 1.647 9.207 9.207 9.207 9.207 9.207 Non Wage 4.401 3.883 0.905 3.883 4.659 5.591 6.710 8.052 Devt. GoU 4.508 4.200 0.031 4.200 4.200 4.200 4.200 4.200 Ext. Fin. 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 GoU Total 15.737 17.290 2.583 17.290 18.067 18.999 20.117 21.459 Total GoU+Ext Fin 15.737 17.290 2.583 17.290 18.067 18.999 20.117 21.459 (MTEF) A.I.A Total 0.476 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 Grand Total 16.213 17.290 2.583 17.290 18.067 18.999 20.117 21.459 (ii) Vote Strategic Objective 1. To produce graduates with positive attitude, hands-on skills and experience, resilience, and favorable global competitiveness. 2. To promote Quality research, innovation and roll out finding for societal transformation. 3. To develop knowledge and information preservation and dissemination Centre at the University. 4. To engage Community with dynamic knowledge, skills, and technology transfer and service partnerships 5. -

FY 2018/19 Vote:553 Soroti District

LG WorkPlan Vote:553 Soroti District FY 2018/19 Foreword Soroti District Local Government Draft Budget for FY 2018/19 provides the Local Government Decision Makers with the basis for informed decision making. It also provides the Centre with the information needed to ensure that the national Policies, Priorities and Sector Grant Ceilings are being observed. It also acts as a Tool for linking the Development Plan, Annual Workplans as well as the Budget for purposes of ensuring consistency in the Planning function This draft budget ZDVDUHVXOWRIFRQVXOWDWLRQZLWKVHYHUDOVWDNHKROGHUVLQFOXGLQJ6XE&RXQW\2IILFLDOVDQG/RFDO&RXQFLORUVDW6XE&RXQW\DQG'LVWULFWDQGLQSXWIURPGHYHORSPHQW partners around the District. This budget is based on the theme for NDPII which is strengthening Uganda's competitiveness for sustainable wealth creation, employment and inclusive growth , productivity tourism development, oil and gas, mineral development, human capital development and infrastructure. The District has prioritized infrastructure development in areas of water, road, Health and Education. With regards to employment creation the district hopes that the funds from </3 <RXWK/LYHOLKRRG3URJUDPPHXQGHU0*/6' ZLOOJRDORQJZD\ZLWKUHJDUGVWR+XPDQFDSLWDOGHYHORSPHQWWKHGLVWULFWZLOOFRQWLQXHWRLPSURYHWKH quality of health care development and market linkage through empowering young entrepreneurs and provision of market information. We will continue to work ZLWKWKRVHGHYHORSPHQWSDUWQHUVWKDWDFFHSWWKHWHUPVDQGFRQGLWLRQVRIWKH0R8VWKDWWKHGLVWULFWXVHVP\WKDQNVJRWRDOOWKRVHZKRSDUWLFLSDWHGLQHYROYLQJWKLV Local Government Budget Frame work paper. I wish to extent my sincere gratitude to the Ministry of Finance Planning and Economic Development and Local Government Finance Commission for coming with the new PBS reporting and budgeting Format that has improved the budgeting process. My appreciation goes to the Sub County and District Council, I also need to thank the Technical Staff who were at the forefront of this work particular the budget Desk. -

Muni University P

MUNI UNIVERSITY P. O. Box 725, Arua Tel: +256-476-420311/2/3 • Board (HESFB). students who have qualified total of 8 Success- for higher education in rec- HESFB’s Peterson Mu- ful loan scheme ognised Higher Education A hanguzi, the Loans Officer in beneficiaries who will be Institutions but are unable to charge of Northern Uganda • studying at Muni University support themselves. and Bob Muwagira, the Sen- beginning 2021/2022 aca- ior Communication Officer The loans are intended to demic year have signed con- were at Muni University on increase equitable access to tracts with the Higher Edu- 28th January 2021, and sen- Technical and Higher educa- cation Students Financing sitised the loan beneficiaries tion and support highly qual- on how they will access and ified Ugandan students who use their packages. may not afford Higher Edu- cation HESFB is a body corporate established by an act of Par- liament, number 2 of 2014, to provide loans and scholar- ships to Ugandan students to pursue higher education. The scheme provides loans and scholarships to Ugandan The University department of Students students organised by the office of the Midwifery made a presentation on preven- affairs has urged continuing students to Dean of Students at the Nursing Science tion and management of COVID 19 includ- observe strict adherence to the Standard Lecture Hall on Jan 20th, the Deputy ing a practical demonstration of the correct Operating Procedures (SOPs) set by the Vice Chancellor, Associate Professor way of disinfecting the hands with a hand Ministry of Health so as to stop con- Simon Anguma Katrini urged the stu- rub. -

Establishment of Soroti University) Instrument, 2015

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT No. 22 16th July, 2015. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS SUPPLEMENT to The Uganda Gazette No. 39, Volume CVIII, dated 16th July, 2015. Printed by UPPC, Entebbe, by Order of the Government. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2015 No. 34. The Universities and Other Tertiary Institutions (Establishment of Soroti University) Instrument, 2015. (Under section 22(1) of the Universities and Other Tertiary Institutions Act, 2001). IN EXERCISE of the powers conferred upon the Minister responsible for Education by section 22(1), 24(1) and 25 of the Universities and Other Tertiary Institutions Act, 2001 and on the recommendation of the National Council for Higher Education, this Instrument is made this 8th day of July, 2015. 1. Title. This Instrument may be cited as the Universities and Other Tertiary Institutions (Establishment of a Soroti University) Instrument, 2015. 2. Establishment of Soroti University. (1) There is established a public University to be known as the Soroti University. (2) The headquarters of the University shall be located in Soroti District in Eastern Uganda. 3. Objects of the University. The objects for which the University is established are— (a) to be the standard of excellence and innovation for societal transformation; 151 (b) to be a leader in integrating scholarship and practice; (c) to serve societal needs and to foster social and economic development; (d) to be global in perspective, organization and action; (e) to engage staff and students in creative and rewarding learning so as to enhance economic and societal development in Uganda and beyond; and (f) to assist local communities and to build their capacity for socio-economic enhancement. -

Soroti-University-Government-Sponsorship-National-Merit-2020-2021-F

22ND/JUNE/2020 GOVERNMENT ADMISSIONS, 2020/2021 ACADEMIC YEAR THE FOLLOWING HAVE BEEN ADMITTED TO THE FOLLOWING PROGRAMME BACHELOR OF MEDICINE AND BACHELOR OF SURGERY COURSE CODE SOM INDEX NO NAME Al Yr SEX C'TRY DISTRICT SCHOOL WT 1 U0027/621 MUTAI Levi 2019 M U 61 KIIRA COLLEGE, BUTIKI 49.6 2 U1076/515 KAJUMBA Ronald 2019 M U 55 HENRY KASULE M.C., KAKIRI 47.8 3 U2511/501 SSEMAGANDA Hakim 2019 M U 42 KASAWO ISLAMIC INSTITUTE 47.7 4 U0334/597 OKELLO Jorem 2019 M U 53 UGANDA MARTYRS S.S., NAMUGONGO 47 5 U0097/562 MUKISA Joshua 2019 M U 81 ST.KALEMBA SECONDARY SCHOOL 46.8 6 U0027/629 MWESIGWA David 2019 M U 17 KIIRA COLLEGE, BUTIKI 46.8 7 U0027/537 GAHUUTU Buraida 2019 M U 11 KIIRA COLLEGE, BUTIKI 46.7 8 U1224/984 TURINAWE Boaz 2019 M U 46 ST MARY'S SS KITENDE 46.7 9 U0024/542 EDOTU Dan 2019 M U 111 SOROTI SECONDARY SCHOOL 46.7 10 U0505/532 KAWOOYA Reagan Jimmy 2019 M U 55 KITENDE S S 46.7 11 U0685/563 MUGUMYA Isaac 2019 M U 41 MITYANA MODERN SS 46.7 12 U0184/515 SSEMUJJU Edsone 2019 M U 40 ST.BALIKUDDEMBE SS MITALA MARIA 46.7 13 U1923/632 ONAP Oscar 2019 M U 94 KIGUMBA INTENSIVE S.S 46.7 14 U1354/501 AKOL Benard 2019 M U 67 MERRYLAND HIGH SCHOOL 46.7 15 U2236/511 KULE Ziste 2019 M U 21 ST.MARY'S COLLEGE, LUGAZI 46.7 16 U1121/538 NALUMAGA Justine 2019 F U 32 WOBULENZI HIGH SCHOOL 45.4 17 U1828/561 NABAASA Racheal 2019 F U 46 STANDARD COLLEGE NTUNGAMO 45.3 18 U1979/551 NANTEGE Phionah 2019 F U 32 GAYAZA CAMBRIDGE COLLEGE 45.3 19 U1873/593 KANYESIGYE Loyce 2019 F U 06 ST. -

BMAU Briefing Paper 24/18: Funding of Public Universities in Uganda

BMAU BRIEFING PAPER (24/18) JUNE 2018 Funding of Public Universities in Uganda: what are the issues? Overview Key Issues The second National Development Plan (NDP II) notes 1. The increase in number of public universities has that public funding to higher education remains at amplified the burden of funding from Ug shs 167.94 0.3% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) which is billion in FY 2012/13 to Ug shs 606.09 billion during below the recommended share of at least 1%. The FY 2017/18. sources of funds for public universities in Uganda are 2. Public universities are not funded sufficiently to cover public, private, and external funding as well as the cost of inputs in order to offer quality education. For the last five years, actual releases have been Internally Generated Funds (IGFs). lower than approved budgets. The major source of funding for university education is 3. Physical infrastructure in public universities has not private funding (parents and individuals). This is grown in tandem with enrollments. followed by government/public funding, external 4. The budgets for non-tax revenue (NTR) in public funding and IGFs respectively. This paper examines universities have been increasing. Public universities public funding of these universities and identifies some are increasingly depending on collection from NTR to deliver the education service. of the critical persistent issues affecting the institutions 5. Funding for research and publication has remained over the period FY 2012/13 to FY 2017/18 that require very low in public universities yet it is their core urgent attention going forward. -

Speech by Professor Christine Dranzoa Vice

SPEECH BY PROFESSOR CHRISTINE DRANZOA VICE CHANCELLOR DESIGNATE, MUNI UNIVERSITY ON THE OCCASION OF THE GROUND-BREAKING CEREMONY AT MUNI UNIVERSITY “Today knowledge has power. It controls access to opportunity & advancement” DATE: 13TH DECEMBER 2011 VERY SPECIAL GUESTS OF MUNI UNIVERSITY Hon. Minister of Education & Sports, (Chief Guest, Hon Lt. (Rtd) Alupo Jessica Rose Epel (MP) Hon. Minister of Health Dr. Christine Ondoa Hon. Minister of State for Higher Education (Hon. Dr. Chrysostom Muyingo) Hon. Minister of State for Finance (General Duties Hon. Fred Jachan-Omach) Hon. Minister of State for Energy (Hon. Simon D’ujanga) Hon. Minister of State for Internal Affairs Hon. Ambassador James Baba Hon. Members of Parliament, Hon. Simon Ejua (former MP Vuraa County) Permanent Secretary, MoES Vice Chancellor, Gulu University Vice Chancellor, Busitema University Vice Chancellor, Mbarara University of Science & Technology Deputy Vice Chancellor, Makerere University Director, HE/BTVET Commissioner Higher Education The South Korean Team led by Professor H. Kook Park The Contractor (Ms Ambitious Constructions Ltd) The Technical Team from Kampala LCV Chairman: Hon. Sam Nyakua Wadri All Hon. LCVs from West Nile Region RDC, Arua District Your Worship the Mayor for Arua Municipality CAO, Arua District Religious Leaders (My Lord Bishops, The District Khadi) All Principals of Constituent Colleges (Both Public and Private Universities Council Members of NTC, Muni LCI Chairman, Oluko Sub County, Muni Village Elders of Oluko Sub County Muni Village Staff of NTC Muni All chairpersons of Head Teachers Association in West Nile Region Representatives from GIZ, Arua Manager Stanbic Bank, Arua All invited Guests and Dignitaries Colleagues from Muni University Ladies & gentlemen You are all most welcome to this very important occasion, marking the ground breaking for Muni University. -

Institutional Design and Utilisation of Evaluation Results in Uganda`S Public Universities: a Case Study of Kyambogo University

INSTITUTIONAL DESIGN AND UTILISATION OF EVALUATION RESULTS IN UGANDA`S PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES: A CASE STUDY OF KYAMBOGO UNIVERSITY BY JAMES KABUYE SEP15/MME/0440U A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND MANAGEMENT IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF A MASTER’S IN MONITORING AND EVALUATION OF UGANDA TECHNOLOGY AND MANAGEMENT UNIVERSITY (UTAMU). AUGUST, 2016 i DECLARATION I, James Kabuye, declare to the best of my knowledge that this work is original and it has not been published and/or submitted for any other degree award to any other University before. Signed: …………………………………………………….. Date ............................................. i APPROVAL This is to certify that this Dissertation titled “ Institutional Design and Utilisation of Evaluation Results in Uganda`s Public Universities: A Case Study of Kyambogo University” was submitted with my approval as the Supervisor: Signature……………………………………………….Date...................................................... Professor Benon C. Basheka, PhD ii DEDICATION This Dissertation is dedicated to my children; Nethaneel and Joanna. iii ACKNOWLEGEMENTS I am so very grateful to God for enabling me to complete a Master’s of Monitoring and Evaluation of UTAMU. I am highly thankful to my Dissertation Supervisor; Professor Benon Basheka, w h o untiringly supervised and guided me at every stage of this Dissertation, more so, by always responding very timely, every time I called. Words of gratitude are owed to my mother for her support, encouragement and material assistance given to me from childhood; my dear wife, Esther and our children: Joanna and Nethaneel as well as Diana; and all my brothers and sisters. In a special way, acknowledgement is made to my elder sister, Joyce, who intervened at the right time in the course of my education. -

Report of the Auditor General on the Financial Statements of Muni University for the Year Ended 30Th June 2018

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF MUNI UNIVERSITY FOR THE YEAR ENDED 30TH JUNE 2018 OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL UGANDA 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS ................................................................................................................................. 2 Key Audit Matters ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Emphasis of matter ................................................................................................................................... 4 Under performance of Non Tax Revenue(NTR) collections ................................................ 4 Other Matter .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Mischarge of expenditure......................................................................................................... 4 Staffing gaps in Academic departments ................................................................................ 5 Undeveloped Land .................................................................................................................... 5 Other Information ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Responsibilities of the Accounting Officer for the Financial Statements ......................................... -

Arua Business Directory.Indd

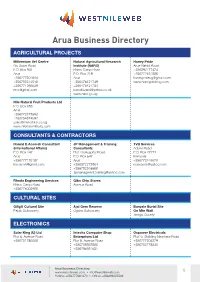

Arua Business Directory AGRICULTURAL PROJECTS Millennium Vet Centre Natural Agricultural Research Honey Pride Go Down Road Institute (NARO) Arua-Nebbi Road P.O. Box 941 Rhino Camp Road +256392177474 Arua P.O. Box 219 +256772451586 +256777301694 Arua [email protected] +256785514518 +256476421749 www.honeyprideug.com +256771296029 +256476421734 [email protected] [email protected] www.naro.go.ug Nile Natural Fruit Products Ltd P.O. Box 685 Arua +256772373692 +256754374692 [email protected] www.nilenaturalfruits.com CONSULTANTS & CONTRACTORS Harold E.Acemah Consultant JP Management & Training TVB Services (International Affairs) Consultants Adumi Road P.O. Box 147 Plot 10,Hospital Road P.O. Box 27772 Arua P.O. Box 647 Kampala +256777175187 Arua +256772446676 [email protected] +256372273964 [email protected] +256782346688 [email protected] Rhoda Engineering Services Gibo Chip Stores Rhino Camp Road Avenue Road +256776002988 CULTURAL SITES Giligili Cultural Site Ajai Gem Reserve Banyale Burial Site Pajulu Subcounty Ogoko Subcounty On Mtn Wati Terego County ELECTRONICS Solar King (U) Ltd Intechs Computer Shop Ospower Electricals Plot 6, Avenue Road Enterprises Ltd Plot14, Building New lane Road +256751786008 Plot 8, Avenue Road +256777204279 +256758353856 +256752778540 +256786931631 Arua Business Directory www.westnileweb.com • [email protected] 1 Hotline: +256777681670 • Office: +256393225533 Metro Electronics Arua Phones Service Centre Aliza Electronic Ltd Plot 10, Duka Road Plot12, Avenue Road Avenue Road +256702144786 +256772822122 +256715089299 +256713144786 Holly Wood Electronics (U) Roman Electronics (U) Ltd Plot1- 3, Adumi Road Adumi Road +256713144786 +256778134910 FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS Centenary Bank Stanbic Bank Bank of Africa Plot 3, Avenue Road Avenue Road Plot 19, Avenue Road P.O. -

Metropolitan Journal of Business & Economics

Editor in Chief Prof. Austin N. Nosike Metropolitan Journal of Business & Economics Vol. 1, No.1, 2020 METROPOLITAN INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Directorate of Research & Innovations access this journal online at www.miu.ac.ug i Metropolitan Journal of Business and Economics Vol. 1, No. 1, 2020 Editor in Chief Prof. Austin N. Nosike Kampala, Uganda ii ISSN 1813-422X(print) Metropolitan Journal of Business and Economics Vol.1, No.1,2020 ISSN 1813-4238(online) Metropolitan International University Press www.miu.edu.ug Metropolitan Journal of Business and Economics Editorial Board Chairman &Vice Chancellor Dr Julius Arinaitwe Editor in Chief Prof. Austin N. Nosike Associate Editor Production Editor Prof. Nwachukwu Ololube Prof Shobana Nelasco Editorial Assistant Project Advisor Dr. Anthony C. Nwali Prof M.A. Mainoma Serial Editor Business Editor Prof M.N. Modebelu Dr Usman Kibon Ado Scientific Director Language Editor Prof. Jacinta A. Opara Prof. Charles Ayo University Secretary Head of Bureau Dr. Ariyo K. Gracious Dr V.O. Charles -Unadike Journal Manager Coordinator Asiimwe Isaac Kazaara Dr Chidiebere Ogbonna The contents of MIU Journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions or position of the Editorial Boards, Metropolitan International University Press or the Governing Council. Neither Metropolitan International University nor any person acting on its behalf is responsible for the use which may be made of the information in the publication. The views published in the journal are entirely those of the authors. The materials printed in our journal are copyright and should not be reproduced without the written permission of the Directorate of Research. Any dispute that may arise relating to the journal shall be peacefully settled by the parties before an agreed Mediation.