State of Doctoral Education and Training in Uganda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Community Education About SARS-Cov-2 Infection in Uganda

HIS0010.1177/1178632920944167Health Services InsightsEchoru et al 944167research-article2020 Health Services Insights University Lecturers and Students Could Help in Volume 13: 1–7 © The Author(s) 2020 Community Education About SARS-CoV-2 Infection Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions in Uganda DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1178632920944167 10.1177/1178632920944167 Isaac Echoru1 , Keneth Iceland Kasozi2 , Ibe Michael Usman3 , Irene Mukenya Mutuku1, Robinson Ssebuufu4 , Patricia Decanar Ajambo4, Fred Ssempijja3, Regan Mujinya3 , Kevin Matama5, Grace Henry Musoke6 , Emmanuel Tiyo Ayikobua7 , Herbert Izo Ninsiima1, Samuel Sunday Dare1,2, Ejike Daniel Eze1,2, Edmund Eriya Bukenya1, Grace Keyune Nambatya8, Ewan MacLeod2 and Susan Christina Welburn2,9 1School of Medicine, Kabale University, Kabale, Uganda. 2Infection Medicine, Deanery of Biomedical Sciences, and College of Medicine & Veterinary Medicine, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK. 3Faculty of Biomedical Sciences, Kampala International University Western, Bushenyi, Uganda. 4Faculty of Clinical Medicine and Dentistry, Kampala International University Teaching Hospital, Bushenyi, Uganda. 5School of Pharmacy, Kampala International University Western Campus, Bushenyi, Uganda. 6Faculty of Science and Technology, Cavendish University, Kampala, Uganda. 7School of Health Sciences, Soroti University, Soroti, Uganda. 8Directorate of Research, Natural Chemotherapeutics Research Institute, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda. 9Zhejiang University-University of Edinburgh -

Bishop Stuart University P.O

BISHOP STUART UNIVERSITY P.O. Box 9 Mbarara Uganda. Tel: +256-4854-22970 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Kampala Liason Offi ce: St. Francis Community Centre Phase II building, 2nd Floor, Room 1 Makerere University. Email: [email protected] Tel: +256-773-724-003 Website: www.bsu.ac.ug INTRODUCTION Medical Services: The University has been blessed with a clinic • Bachelor of Animal Health and Producti on (BAHP)* • Bachelor of Banking and Investment Management (BBIM) Under the guidance of lecturers, the students of the faculty will Bishop Stuart University is a not-for-profi t Chartered educati onal which is manned by well trained nurses. For referrals, the pati ents • Bachelor of Sports Science (BSS) • Bachelor of Project Planning and Management (BPPM)* be conducti ng clinics to assist people with various legal problems, insti tuti on established by Ankole Diocese of the Province of the are referred to Ruharo Mission Hospital with which the university • Diploma in Midwifery (DMW) • Bachelor of Procurement and Supply Chain Management such as accessing justi ce, issues if domesti c violence, matt ers of has a partnership/health scheme. Anglican Church of Uganda to provide Christi an based higher • Advanced Certi fi cate in Appropriate and Sustainable (BPSCM)* succession. They will be writi ng to sensiti ze communiti es about Technologies (ACAST) • Bachelor of Community Psychology (BCP)* their rights, such as the right to a clean environment, the right to Educati on, training and research for the expansion of God’s Students Clubs: Many clubs and associati ons are progressively The university got an opportunity of sending its students of • Bachelor of Records Management and Informati on Science educati on, the right to health and the right to shelter, land rights kingdom, human Knowledge and bett erment of society. -

Vote:127 Muni University

Education Vote Budget Framework Paper FY 2020/21 Vote:127 Muni University V1: Vote Overview (i) Snapshot of Medium Term Budget Allocations Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures Billion Uganda Shillings FY2018/19 FY2019/20 FY2020/21 MTEF Budget Projections Approved Spent by Proposed 2021/22 2022/23 2023/24 2024/25 Outturn Budget End Sep Budget Recurrent Wage 6.828 9.207 1.647 9.207 9.207 9.207 9.207 9.207 Non Wage 4.401 3.883 0.905 3.883 4.659 5.591 6.710 8.052 Devt. GoU 4.508 4.200 0.031 4.200 4.200 4.200 4.200 4.200 Ext. Fin. 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 GoU Total 15.737 17.290 2.583 17.290 18.067 18.999 20.117 21.459 Total GoU+Ext Fin 15.737 17.290 2.583 17.290 18.067 18.999 20.117 21.459 (MTEF) A.I.A Total 0.476 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 Grand Total 16.213 17.290 2.583 17.290 18.067 18.999 20.117 21.459 (ii) Vote Strategic Objective 1. To produce graduates with positive attitude, hands-on skills and experience, resilience, and favorable global competitiveness. 2. To promote Quality research, innovation and roll out finding for societal transformation. 3. To develop knowledge and information preservation and dissemination Centre at the University. 4. To engage Community with dynamic knowledge, skills, and technology transfer and service partnerships 5. -

Govt Takes Over Running of Busoga University

12 NEW VISION, Tuesday, February 6, 2018 REGIONAL NEWS Govt takes over running of Busoga University Amuru leaders clash KAMULI Authorities in Amuru have By Tom Gwebayanga National Forest Authority (NFA) over a planned re-opening of the The Government has announced boundaries of Olwal Central Forest its decision to take over the Reserve. Olwal Forest Reserve is management of the stressed private located in Olwal village, Giragira Busoga University in a bid to end parish, Lamogi sub-county in Amuru the woes that have rocked the district. It covers 1,384 hectares institution for over six years, the of land. The leaders, who included Speaker of Parliament, Rebecca Kilak South MP Gilbert Olanya Kadaga, has said. and Amuru LC5 chairman Michael Kadaga said President Yoweri Lakony, demanded that NFA Museveni last week okayed the stop planting mark stones along takeover of Busoga University to the boundaries of Olwal Forest relieve the public of last year’s tension as a result of its closure to plant the mark stones last week by the National Council for Higher because the leaders and residents Education (NCHE). protested the re-opening of the “It is over; the people of Busoga boundaries of the forest reserve, and beyond have every reason to claiming that NFA wants to grab smile,” Kadaga said. She said amidst the troubles of the bullets in the air to stop youth from university, a blessing has come after reloading the mark stones onto the President Museveni gave a directive NFA vehicle that had brought them. that the government takes over full control of the university, which is on the brink of collapse. -

FY 2018/19 Vote:553 Soroti District

LG WorkPlan Vote:553 Soroti District FY 2018/19 Foreword Soroti District Local Government Draft Budget for FY 2018/19 provides the Local Government Decision Makers with the basis for informed decision making. It also provides the Centre with the information needed to ensure that the national Policies, Priorities and Sector Grant Ceilings are being observed. It also acts as a Tool for linking the Development Plan, Annual Workplans as well as the Budget for purposes of ensuring consistency in the Planning function This draft budget ZDVDUHVXOWRIFRQVXOWDWLRQZLWKVHYHUDOVWDNHKROGHUVLQFOXGLQJ6XE&RXQW\2IILFLDOVDQG/RFDO&RXQFLORUVDW6XE&RXQW\DQG'LVWULFWDQGLQSXWIURPGHYHORSPHQW partners around the District. This budget is based on the theme for NDPII which is strengthening Uganda's competitiveness for sustainable wealth creation, employment and inclusive growth , productivity tourism development, oil and gas, mineral development, human capital development and infrastructure. The District has prioritized infrastructure development in areas of water, road, Health and Education. With regards to employment creation the district hopes that the funds from </3 <RXWK/LYHOLKRRG3URJUDPPHXQGHU0*/6' ZLOOJRDORQJZD\ZLWKUHJDUGVWR+XPDQFDSLWDOGHYHORSPHQWWKHGLVWULFWZLOOFRQWLQXHWRLPSURYHWKH quality of health care development and market linkage through empowering young entrepreneurs and provision of market information. We will continue to work ZLWKWKRVHGHYHORSPHQWSDUWQHUVWKDWDFFHSWWKHWHUPVDQGFRQGLWLRQVRIWKH0R8VWKDWWKHGLVWULFWXVHVP\WKDQNVJRWRDOOWKRVHZKRSDUWLFLSDWHGLQHYROYLQJWKLV Local Government Budget Frame work paper. I wish to extent my sincere gratitude to the Ministry of Finance Planning and Economic Development and Local Government Finance Commission for coming with the new PBS reporting and budgeting Format that has improved the budgeting process. My appreciation goes to the Sub County and District Council, I also need to thank the Technical Staff who were at the forefront of this work particular the budget Desk. -

Of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya Kevin Brennan

A History of the Absence (and Emergent Presence) of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya Kevin Brennan A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: George Noblit Julius Nyang‟oro James Trier Richard Rodman Gerald Unks © 2008 Kevin Brennan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Kevin Brennan A History of the Absence (and Emergent Presence) of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya (Under the direction of George Noblit and Julius Nyang‟oro) While there is a great deal of literature available about schooling in Kenya and a good deal of writing about the establishment of Kenya‟s public university system there is a significant gap in the literature when it comes to describing and analyzing why certain areas of the country had long been removed from any on-site development of independent university opportunities. This study is an attempt to offer a history of an educational institution – an independent public university at the coast in Kenya – that does not yet exist. This longstanding absence took several significant steps toward transforming to a presence in 2007, when several university colleges were created at the coast. This transformation from absence to presence is a central theme in this work. The research for this project, broadly defined, took place over a seventeen year period and is rooted in both the author‟s professional experience as an educator working in Kenya in the early 1990s as well as his academic interests in comparative and international higher education. -

Muni University P

MUNI UNIVERSITY P. O. Box 725, Arua Tel: +256-476-420311/2/3 • Board (HESFB). students who have qualified total of 8 Success- for higher education in rec- HESFB’s Peterson Mu- ful loan scheme ognised Higher Education A hanguzi, the Loans Officer in beneficiaries who will be Institutions but are unable to charge of Northern Uganda • studying at Muni University support themselves. and Bob Muwagira, the Sen- beginning 2021/2022 aca- ior Communication Officer The loans are intended to demic year have signed con- were at Muni University on increase equitable access to tracts with the Higher Edu- 28th January 2021, and sen- Technical and Higher educa- cation Students Financing sitised the loan beneficiaries tion and support highly qual- on how they will access and ified Ugandan students who use their packages. may not afford Higher Edu- cation HESFB is a body corporate established by an act of Par- liament, number 2 of 2014, to provide loans and scholar- ships to Ugandan students to pursue higher education. The scheme provides loans and scholarships to Ugandan The University department of Students students organised by the office of the Midwifery made a presentation on preven- affairs has urged continuing students to Dean of Students at the Nursing Science tion and management of COVID 19 includ- observe strict adherence to the Standard Lecture Hall on Jan 20th, the Deputy ing a practical demonstration of the correct Operating Procedures (SOPs) set by the Vice Chancellor, Associate Professor way of disinfecting the hands with a hand Ministry of Health so as to stop con- Simon Anguma Katrini urged the stu- rub. -

Undergraduate Private Admissions 2020/2021 Academic Year

MBARARA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY OFFICE OF THE ACADEMIC REGISTRAR P.O. Box 1410, MBARARA-UGANDA Telephone: +256-485-660584, +256-414-668971 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Web: www.must.ac.ug UNDERGRADUATE PRIVATE ADMISSIONS 2020/2021 ACADEMIC YEAR The following have been admitted to the different programmes as below for the 2020/2021 academic year. Admission letters shall be sent by email to applicants who have paid a NON-REFUNDABLE TUITION FEES DEPOSIT of Shs. 50,000=. Visit www.must.ac.ug for instructions on how to pay or contact us by email [email protected] or WhatsApp us on +256-786-706490. BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN COMPUTER ENGINEERING SN NAME GENDER NATIONALITY DISTRICT ALEVEL_INDEX YEAR WEIGHT 1 BATAMYE ABDUL M Ugandan BUIKWE U1609/635 2019 47.1 2 BONGO JOSHUA M Ugandan APAC U2060/581 2019 44.2 3 KIA JANET F Ugandan ALEBTONG U1923/610 2019 43.7 4 NSHEKANABO MARIUS M Ugandan SHEEMA U1063/563 2019 41.3 5 BINTO NAOMI F Ugandan MUKONO U2583/568 2019 40.7 6 BWAMBALE ROBERT SEMAKULA M Ugandan KASESE U3231/514 2019 31.5 7 MUTEBI JONATHAN M Ugandan WAKISO U0053/823 2019 31.2 8 ARINAITWE JULIUS M Ugandan MBARARA U1495/554 2017 31.1 9 ATWIINE SAGIUS M Ugandan NTUNGAMO U0946/572 2019 28.0 10 KISAKYE JULIUS M Ugandan IGANGA U0027/564 2019 27.6 11 MUKWATANISE ALBERT M Ugandan ISINGIRO U0334/692 2019 27.6 12 MATEGE DERICK M Ugandan KAMULI U2877/614 2012 27.1 13 MUHUMUZA JOSEPH M Ugandan KISORO U0080/566 2019 25.2 14 MWEBESA TREVOR M Ugandan NTUNGAMO U0053/827 2019 25.2 15 KAANYI JANE PATIENCE F Ugandan KIBUKU U0065/586 -

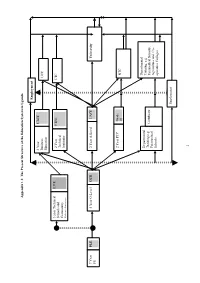

Appendix 1.1: the Present Structure of the Education System in Uganda

Appendix 1.1: The Present Structure of the Education System in Uganda Employment 3 Year UBEE Business UCC Education 3 year Technical UJTE 2 Year UTEE UTC Schools and Technical Community Institutes Polytechniques 7 Year PLE 4 Year O-Level UCE 2 Year A-Level UACE University PS 2 Year PTC Grade III NTC Departmental Departmental Training, e.g Training e.g. Certificate Paramedical Schools, Paramedical Agriculture and Co- Schools operative Colleges Employment I Appendix 1.2a: List of some of the Institutions of Higher Learning in Uganda (Universities (Public and Private) and Public other Tertiary Institutions as per May, 2005) b) Uganda Technical College (UTC)2 1. Universities • UTC Kichwamba • UTC Elgon a) Public • UTC Lira • Makerere University • UTC Masaka • Mbarara University of Science and • UTC Bushenyi Technology • Kyambogo University c) National Teachers’ Colleges (NTC) • Gulu University • NTC Unyama • NTC Kabale b) Public Degree Awarding Other Tertiary • NTC Nagongera Institution • NTC Muni • Uganda Management Institute1 • NTC Kaliro • NTC Mubende c) Private: Chartered Universities • Islamic University in Uganda d) Departmental Training Institutions • Uganda Christian University, Mukono • Uganda Martyrs University (Nkozi) i) Paramedical Schools • Arua Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery d) Private: Licensed to Operate • Butabika Psychiatric Clinical Officers • Bugema University • Butabika School of Nursing • Nkumba University • Fort Portal Clinical Officers School • Kampala International University • Gulu Clinical Officers School • Kampala University • Jinja Nurses and Midwifery • Ndejje University • Kabale Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery • Busoga University • Lira Enrolled Nurses and Midwifery • Kumi University • Masaka School of Comprehensive • Aga Khan University Nursing • Kabale University • Mbale Clinical Officers School • Mountains of the Moon University • Mbale School of Hygiene • Uganda Pentecostal University • Medical Laboratory School, Mulago • African Bible College • Medical Laboratory School, Jinja • Mulago Health Tutors College 2. -

Call for Applications Master of Public Health with Research Ethics

MBARARA UNIVERSITY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Office of the Academic Registrar P. O. Box 1410 Mbarara, Uganda Tel: +256-414-668971 Email: [email protected] CALL FOR APPLICATIONS MASTER OF PUBLIC HEALTH WITH RESEARCH ETHICS Applications are invited from eligible candidates for a Master of Public Health programme with a focus on Research Ethics, offered at Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST), Department of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine. The programme has two (2) available scholarships sponsored by The Mbarara University Research Ethics Education Program (MUREEP) with funding from Fogarty International Centre - National Institutes of Health (USA). Course Duration: 2 YEARS MINIMUM ENTRY REQUIREMENTS FEES STRUCTURE a) Uganda Certificate of Education (UCE) or its equivalent Ugandans with at least 5 passes obtained at the same sitting. Application fees Ug. Shs. 52,750/= b) Uganda Advanced Certificate of Education (UACE) or its Tuition fees Ug. Shs. 1,750,000= per semester equivalent with at least 2 principal passes obtained at the Functional fees Ug. Shs. 1,270,000= per annum same sitting. c) An Honors degree from an accredited degree awarding International Students institution in a relevant field with a minimum CGPA of 2.8. Application fees US $ 50 d) Targeted applicants should have previous training in at Tuition US $ 2,250 per semester least one of these areas: Biological sciences, Health Functional fees US $ 1,740 per annum Sciences or Social sciences. SCHOLARSHIP DETAILS MUREEP will provide 2 scholarships on a competitive basis for staff of Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Bishop Stuart University, Kabale University, Kampala International University and other individuals involved in Research. -

1 Office of the Academic Registrar 1. Fees Structure

OFFICE OF THE ACADEMIC REGISTRAR The University invite applications for the following academic programmes scheduled to start in August 2019 1. FEES STRUCTURE FOR THE UNDERGRADUATE ACADEMIC PROGRAMMES 2019-2020 DURATION TUITION (Years) (Ush) per OTHER FEES (Ush) SESSION PROGRAMES Semester per Semester FACULTY OF APPLIED SCIENCES Bachelor of Science in Agricultural Economics and Resource Management 3 919,600 356,000 Regular/Weekend Bachelor of Public Health 3 1,078,000 386,000 Regular/Weekend Bachelor of Nursing Science 4 1,318,900 386,000 Regular/Weekend Bachelor of Nursing Science Completion 3 1,318,900 386,000 Regular/Weekend Bachelor of Animal Health and Production 3 1,078,000 356,000 Regular/Weekend Bachelor of Computer Science 3 986,150 356,000 Regular/Weekend Bachelor of Agribusiness Management and Community Development 3 892,900 356,000 Regular/Weekend Bachelor of Sports Science 3 1,078,000 356,000 Regular/Weekend Bachelor of Information Technology 3 986,150 356,000 Regular/Weekend Bachelor of Agriculture and Community Development 3 919,600 356,000 Regular/Weekend Diploma in Computer Science 2 719,950 356,000 Regular/Weekend Diploma in Midwifery Extension (July Intake) 1 & ½ 1,056,000 386,000 Regular/Weekend Diploma in Nursing Science 2 1,052,700 386,000 Regular/Weekend Diploma in Nursing Extension (July Intake) 1 & ½ 1,052,700 386,000 Regular/Weekend Diploma in Public Health 2 715,000 356,000 Regular/Weekend Diploma in Agribusiness Management and Community Development 2 626,780 356,000 Regular/Weekend Diploma in Information Technology -

Bishop Stuart University

BISHOP STUART UNIVERSITY A LIST OF APPLICANTS WHO HAVE BEEN SELECTED FOR ADMISSION TO THE VARIOUS ACADEMIC PROGRAMS FOR THE AY 2020/2021 FACULTY OF EDUCATION, ARTS AND MEDIA STUDIES 1. BACHELOR OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION (BAJMC) # Name Program 1 AINOMUJUNI ANTHONY BACHELOR OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION BACHELOR OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION 2 TUMURANZYE BRAVE BACHELOR OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION 3 ANKUNDA SHILLAH BACHELOR OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION 4 AGUME DAVIS BACHELOR OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION 5 MUHINDA PAUL BACHELOR OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION 6 MURAMUZI PRICHARD BACHELOR OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION 7 BARIGYE SHARON 2. DIPLOMA IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION (DJMC) # Name Program 1 AGABA ALLAN DIPLOMA IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION 2 AYESIGA JULIET DIPLOMA IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION 3 NASASIRA EDINAH DIPLOMA IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION 4 KATABAZI ABDUL DIPLOMA IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION 5 NYESIGA RHITAH DIPLOMA IN JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION 3. BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH EDUCATION (BAED) # Name Program COMB 1 MUGUME DEVISON BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH EDUCATION ENT/HIST 2 NUWAGABA IVAN BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH EDUCATION ENG/LIT 3 KWARISIIMA GIFT BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH EDUCATION FINEART DM 4 ATUMUHAIRE CLAIRE BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH EDUCATION HIST/GEO 5 ATWINE MACKLINE BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH EDUCATION KISWAHILI DM 6 KWESIGA AGGREY BACHELOR OF ARTS WITH EDUCATION HIST/RS