Nkumba Business Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stichting Porticus

CATHOLIC SCHOLARSHIP PROGRAMME FOR UGANDA C/o University of Kisubi P.O. Box 182 Entebbe, Uganda Photograph Tel. +256 777 606093 Email: [email protected] APPLICATION FORM Please be advised that the eligibility requirements for the Scholarship Programme have changed in 2019; please refer to the Catholic Scholarship Programme Eligibility Requirements, 2019 which are attached as Annex A. Each applicant must write a Personal Statement, please follow the template attached as Annex B. Each applicant must have two (2) Letters of Recommendation, including one from your superior. Please follow the template attached as Annex C. Finally, this application should be submitted together with the list of documents on page 4. PERSONAL DETAILS Surname:…………………………………………………… First and Middle names: …….……………………….……………………. Other names ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………...…………..………..……… Date of birth: ………………………………...... Place of birth: …………………………………..…………….................... Nationality: ………………………………………. Identity card no/ Passport no:…….…..………………………...……… Religious ☐ Lay ☐ Mobile phone numbers: ………………….…………….…................. E-mail: ……………………………………………………………………………………………. Gender: ……….……………………..……………. Permanent address: …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……...……….. Name of Nominating Institution (the Congregation or organization that is nominating the student for a scholarship): ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………….……. Local Congregation:………………………………………. Pontifical Institute……………………………………………..………………. Superior/Next -

THE REPUBLIC of UGANDA in the CHIEF MAGISTRATES COURT of ENTEBBE at ENTEBBE CRIMINAL REGISTRY CAUSELIST for the SITTINGS of : 31-08-2020 to 04-09-2020

8/31/2020 Court Case Administration System THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA IN THE CHIEF MAGISTRATES COURT OF ENTEBBE AT ENTEBBE CRIMINAL REGISTRY CAUSELIST FOR THE SITTINGS OF : 31-08-2020 to 04-09-2020 MONDAY, 31-AUG- 2020 CHIEF MAGISTRATE BEFORE:: ALUM AGNES Case Case Nature of Time Pares Charge CRB No Sing Type number Category Appl./Appeal UGANDA VS ENT-00-CR- ASP Hearing - Criminal ATTEMPTED Kajjansi/CRB 1. 09:00 CO-0506- AMUTUHAIRE prosecuon Offence ROBBERY 762/2019 2019 BRIGHT & case ANOR ENT-00-CR- UGANDA VS Hearing - Criminal ATTEMPT TO Entebbe Police 2. 09:00 CO-0306- AGABA prosecuon Offence MURDER Staon/CRB 491/2020 2020 ROBERT case UGANDA VS ENT-00-CR- Hearing - Criminal MASABA 3. 09:00 CO-0089- Kisubi/197/2019 prosecuon Offence GEORGE 2020 case WILLIS ENT-00-CR- UGANDA VS UTTERING Hearing - Criminal Aviaon Security 4. 09:00 CO-0573- BIZIMANA FALSE prosecuon Offence Police/CRB:184/2019 2019 ERIC DOCUMENTS case ENT-00-CR- UGANDAQ VS Hearing - Criminal Entebbe Police 5. 09:00 CO-0323- KAMANYA prosecuon Offence Staon/545/2020 2020 MIKE case MAGISTRATE GRADE I BEFORE:: BIRUNGI PHIONAH Case Case Nature of Time Pares Charge CRB No Sing Type number Category Appl./Appeal ENT-00-CR- Entebbe Police Criminal UGANDA VS CRIMINAL 1. 09:00 CO-0678- Staon/CRB Ruling Offence KIRUME JOHN TRESSPASS 2018 1043/2017 ENT-00-CR- UGANDA VS Criminal Hearing 2. 09:00 CO-0398- BUKOMEKO Kasanje/21/2019 Offence (unspecified) 2019 MIKE ENT-00-CR- UGANDA VS Hearing - Criminal Entebbe Police 3. 09:00 CO-0060- NAKAKAWA THEFT prosecuon Offence Staon/1380/2019 2020 REMMY case UGANDA VS ENT-00-CR- Hearing - Criminal NAMUNYO 4. -

Losing Ground.Pdf

The Unprecedented Shrinking of Public Spaces LOSING and Land in Ugandan GROUND? Municipalities A publication of the Cities Alliance Joint Work Programme for Equitable Economic Growth in Cities By Paul. I. Mukwaya, Dmitry Pozhidaev, Denis Tugume, and Peter Kasaija © UNCDF and Cities Alliance 2018 AUTHORS Paul. I. Mukwaya, Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Dmitry Pozhidaev, United National Capital Development Fund, Kampala, Uganda Denis Tugume, Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda Peter Kasaija, Department of Geography, Geo-informatics and Climatic Sciences, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda JWP MANAGEMENT AND COORDINATION Rene Peter Hohmann, Cities Alliance Fredrik Bruhn, Cities Alliance GRAPHIC DESIGN Creatrix Design Group This publication was produced by Cities Alliance and the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) as part of the Cities Alliance Joint Work Programme (JWP) for Equitable Economic Growth in Cities. The U.K. Department for International Development (DFID) chairs the JWP, and its members are the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), UN-Habitat, Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO), Commonwealth Local Government Forum (CLGF), Ford Foundation, Institute for Housing and Development Studies (IHS) at Erasmus University Rotterdam and the World Bank. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the Cities Alliance, the United Nations, including UNCDF and UNOPS, or the UK Department for International Development (DFID). 2 Losing Ground? SUMMARY There is increasing importance being attached to is to promote economic growth that benefits ALL public spaces and other municipal assets, such as citizens. -

Parenting Styles and Students' Academic Performance

PARENTING STYLES AND STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE OF SENIOR TWO AND SENIOR FIVE STUDENTS IN MASULIITA TOWN COUNCIL: A CASE OF SELECTED SECONDARY SCHOOLS BY KYOBE CHARLES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION HUMANITIES AND SCIENCES OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF A MASTER’S DEGREE EDUCATION MANAGEMENT AND PLANNING OF NKUMBA UNIVERSITY OCTOBER, 2018 1 DECLARATION I, Kyobe Charles, hereby declare that this research report is my original work and to the best of my knowledge, it has never been submitted for any academic award in this or any other institution of higher learning. i APPROVAL This dissertation titled “PARENTING STYLES AND STUDENTS’ ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE OF SENIOR TWO AND SENIOR FIVE STUDENTS IN MASULIITA TOWN COUNCIL: A CASE OF SELECTED SECONDARY SCHOOLS” has been prepared by Kyobe Charles under my supervision and it is now ready for submission. ii DEDICATION I dedicate this dissertation to my loving and caring family for the sacrifices made in supporting my studies. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to thank the Almighty God who has brought me this far in my life, and has kept me safe to this stage. I pray that he can give me more countless years so that I can serve him relentless. I wish to thank my Superior General the Archbishop of Kampala Archdiocese Dr. Cyprian Kizito Lwanga, the Vicar General Monsignor Charles Kasibante and my Rector Reverend Father Ceasar Matovu, and my spiritual director Reverend Father Emmanuel Kasajja for all the support you have accorded throughout my academic endavours to this stage. To my dear parents; Mr. -

Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) 2.0 Programs Bi-Annual Performance Report Narrative

Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN) 2.0 Programs Bi-Annual Performance Report Narrative 1. BACKGROUND LASER PULSE is a five-year USAID-funded consortium, led by Purdue University and also comprising Catholic Relief Services, Indiana University, Makerere University, and the University of Notre Dame. LASER PULSE supports the research-to-translation value chain through a global network of 1,000+ researchers, government agencies, non-governmental organizations, and the private sector for research-driven, practical solutions to critical development challenges in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). LASER supports the discovery and uptake of research-sourced, evidence-based solutions to development challenges spanning all USAID technical sectors and global geographic regions. The LASER PULSE strategy ensures that applied research is co-designed with development practitioners, and results in solutions that are useful and usable. LASER does this by involving development practitioners upfront - from topic selection, research question definition, conducting and testing research, and developing translation products for immediate use. We support this process with capacity building and technical assistance to enable the researcher/user partnerships to function effectively. 2. MAJOR MILESTONES / ACHIEVEMENTS 1. Researcher Capacity: Makerere University had an opportunity to engage with USAID Uganda’s Regional Development Initiative. The team accompanied the Uganda Regional Development Initiative team on several visits, to provide feedback on working with local universities in order to enhance their role in the path to self-reliance. This is a model that can be replicated in other countries and regions. The collaboration (Makerere and RDI) has resulted in a new buy-in opportunity for Makerere to work with regional universities in strengthening resilience for indigenous Ugandan groups). -

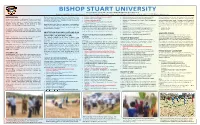

Bishop Stuart University P.O

BISHOP STUART UNIVERSITY P.O. Box 9 Mbarara Uganda. Tel: +256-4854-22970 Email: [email protected], [email protected] Kampala Liason Offi ce: St. Francis Community Centre Phase II building, 2nd Floor, Room 1 Makerere University. Email: [email protected] Tel: +256-773-724-003 Website: www.bsu.ac.ug INTRODUCTION Medical Services: The University has been blessed with a clinic • Bachelor of Animal Health and Producti on (BAHP)* • Bachelor of Banking and Investment Management (BBIM) Under the guidance of lecturers, the students of the faculty will Bishop Stuart University is a not-for-profi t Chartered educati onal which is manned by well trained nurses. For referrals, the pati ents • Bachelor of Sports Science (BSS) • Bachelor of Project Planning and Management (BPPM)* be conducti ng clinics to assist people with various legal problems, insti tuti on established by Ankole Diocese of the Province of the are referred to Ruharo Mission Hospital with which the university • Diploma in Midwifery (DMW) • Bachelor of Procurement and Supply Chain Management such as accessing justi ce, issues if domesti c violence, matt ers of has a partnership/health scheme. Anglican Church of Uganda to provide Christi an based higher • Advanced Certi fi cate in Appropriate and Sustainable (BPSCM)* succession. They will be writi ng to sensiti ze communiti es about Technologies (ACAST) • Bachelor of Community Psychology (BCP)* their rights, such as the right to a clean environment, the right to Educati on, training and research for the expansion of God’s Students Clubs: Many clubs and associati ons are progressively The university got an opportunity of sending its students of • Bachelor of Records Management and Informati on Science educati on, the right to health and the right to shelter, land rights kingdom, human Knowledge and bett erment of society. -

October 21 2017 Thesis New Changes Tracked

The Status, Rights and Treatment of Persons with Disabilities within Customary Legal Frameworks in Uganda: A Study of Mukono District By David Brian Dennison BA (honours), MBA, JD (cum laude) (University of Georgia, USA) Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Private TownLaw Faculty of Law UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN Cape of Date of submission: 31 October 2017 Supervisor: Professor Chuma Himonga University Department of Private Law University of Cape Town The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derivedTown from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes Capeonly. of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University The copyright for this thesis rests with the University of Cape Town. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgment of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non-commercial research purposes only. "ii ABSTRACT Thesis Title: The Status, Rights and Treatment of Persons with Disabilities within Customary Legal Frameworks in Uganda: A Study of Mukono District Submitted by: David Brian Dennison on 31 October 2017 This thesis addresses the question: How do customary legal frameworks impact the status, rights and treatment of persons with disabilities? It is motivated by two underlying premises. First, customary legal frameworks are highly consequential in Sub-Saharan contexts. -

Govt Takes Over Running of Busoga University

12 NEW VISION, Tuesday, February 6, 2018 REGIONAL NEWS Govt takes over running of Busoga University Amuru leaders clash KAMULI Authorities in Amuru have By Tom Gwebayanga National Forest Authority (NFA) over a planned re-opening of the The Government has announced boundaries of Olwal Central Forest its decision to take over the Reserve. Olwal Forest Reserve is management of the stressed private located in Olwal village, Giragira Busoga University in a bid to end parish, Lamogi sub-county in Amuru the woes that have rocked the district. It covers 1,384 hectares institution for over six years, the of land. The leaders, who included Speaker of Parliament, Rebecca Kilak South MP Gilbert Olanya Kadaga, has said. and Amuru LC5 chairman Michael Kadaga said President Yoweri Lakony, demanded that NFA Museveni last week okayed the stop planting mark stones along takeover of Busoga University to the boundaries of Olwal Forest relieve the public of last year’s tension as a result of its closure to plant the mark stones last week by the National Council for Higher because the leaders and residents Education (NCHE). protested the re-opening of the “It is over; the people of Busoga boundaries of the forest reserve, and beyond have every reason to claiming that NFA wants to grab smile,” Kadaga said. She said amidst the troubles of the bullets in the air to stop youth from university, a blessing has come after reloading the mark stones onto the President Museveni gave a directive NFA vehicle that had brought them. that the government takes over full control of the university, which is on the brink of collapse. -

Of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya Kevin Brennan

A History of the Absence (and Emergent Presence) of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya Kevin Brennan A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Education. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: George Noblit Julius Nyang‟oro James Trier Richard Rodman Gerald Unks © 2008 Kevin Brennan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Kevin Brennan A History of the Absence (and Emergent Presence) of Independent Public Universities in Mombasa, Kenya (Under the direction of George Noblit and Julius Nyang‟oro) While there is a great deal of literature available about schooling in Kenya and a good deal of writing about the establishment of Kenya‟s public university system there is a significant gap in the literature when it comes to describing and analyzing why certain areas of the country had long been removed from any on-site development of independent university opportunities. This study is an attempt to offer a history of an educational institution – an independent public university at the coast in Kenya – that does not yet exist. This longstanding absence took several significant steps toward transforming to a presence in 2007, when several university colleges were created at the coast. This transformation from absence to presence is a central theme in this work. The research for this project, broadly defined, took place over a seventeen year period and is rooted in both the author‟s professional experience as an educator working in Kenya in the early 1990s as well as his academic interests in comparative and international higher education. -

Kampala Industrial and Business Park Infrastructure Scheme

Kampala Industrial and Business Park Infrastructure Scheme ESIA Volume I: Non-Technical Summary June 2019 QUEENSLAND & LEEDS CONSULTING ENGINEERS LTD QUEENSLAND & LEEDS CONSULTING ENGINEERS LTD 27 Binayomba Road Bugolobi PO Box 22428 Kampala, Uganda +256 414268466 Queensland.Leeds@engine er.com QUEENSLAND & LEEDS CONSULTING ENGINEERS LTD Kampala Industrial and 408382 ESIA-I A Business https://mottmac.sharepoint.com/teams/pj-d2237/do/Develop/02-Working Park documents/03_ESIA/Volume I Non-Technical Summary - JV Template.docx Infrastructure Queensland & Leeds Scheme ESIA Volume I: Non-Technical Summary June 2019 QUEENSLAND & LEEDS CONSULTING ENGINEERS LTD Registered number 80020001207621 Queensland & Leeds | Kampala Industrial and Business Park Infrastructure Scheme ESIA Volume I: Non-Technical Summary Information class: Standard This document is issued for the party which commissioned it and for specific purposes connected with the above- captioned project only. It should not be relied upon by any other party or used for any other purpose. We accept no responsibility for the consequences of this document being relied upon by any other party, or being used for any other purpose, or containing any error or omission which is due to an error or omission in data supplied to us by other parties. This document contains confidential information and proprietary intellectual property. It should not be shown to other parties without consent from us and from the party which commissioned it. 408382 | ESIA-I | A | June 2019 Queensland & Leeds | Kampala Industrial and Business Park Infrastructure Scheme ESIA Volume I: Non-Technical Summary Contents Non-Technical Summary 1 Introduction 1 The Scheme 1 The Assessment 2 Environmental and Social Management Plan 8 What Happens Next? 8 408382 | ESIA-I | A | June 2019 The Namanve Forest Reserve is located to the south, with the KIBP proposed Non-Technical Summary to take 0.95km2 of this area. -

Disclosing Cultural Narrative and Identity Through Art Practices in Uganda Maria Palmo

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Doctoral Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects 2010 The ra tistic process in community development : disclosing cultural narrative and identity through art practices in Uganda Maria Palmo Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/diss Recommended Citation Palmo, Maria, "The ra tistic process in community development : disclosing cultural narrative and identity through art practices in Uganda" (2010). Doctoral Dissertations. 377. https://repository.usfca.edu/diss/377 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of San Francisco THE ARTISTIC PROCESS IN COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT: DISCLOSING CULTURAL NARRATIVE AND IDENTITY THROUGH ART PRACTICES IN UGANDA A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Leadership Studies Department Organization and Leadership Program In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education by Maria Palmo San Francisco Spring 2010 THE UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO Dissertation Abstract The Artistic Process in Community Development: Disclosing Cultural Narrative and Identity Through Art Practices in Uganda This research studies the use of art as a transformative medium for community development in contemporary Uganda. The focus of this research is on the creative process of art practices and how these processes may raise development issues to the level of discourse. -

Culture of Uganda

Notes for the Teacher / Guide THE CULTURE OF UGANDA The aim of this project is to introduce the children in the UK to the culture and traditions of Traditions and culture an African country Uganda. Ugandan Dance The culture of Uganda is colourful, interesting and diverse. It is based on the traditions of the Songs of Uganda country, which go back centuries and are bound up Musical Instruments with religion and rituals. The traditions are handed down from generation to generation and Poetry each dance or song is imbued with meaning. Ceremonial dress Culture is important as it gives identity to a nation, and the people are true to their roots. UGANDAN DANCE “The various dances in Uganda come from the various different tribal cultural values as we have many different tribes with different cultures from our ancestors. There are particular dances for both girls and boys according to the different tribes. The children have music lessons and dance lessons, especially in preparation for particular functions, such as welcoming people. The children very much enjoy the Baganda dance known as the Kiganda dance. This involves singing, clapping hands, dancing to the cultural rhythm created by instruments such as drums and xylophones. The children put on a particular dress which demonstrates their culture. The traditional dancing originates from their ancestors who introduced and evolved these traditional dances to express their cultural tribal values. These traditional dances are also used by children to charity no 1098176 HUGS welcome people”. SONGS OF UGANDA “Songs are passed down through generations, from great grandparents and grandparents, to their children.